At first, this article was going to be a grumbling about well-known ideas like: "Let's add support for objects in Bash instead of ObSoLeTe text and add support for images and GIFs in the commands' output."

But as I was writing it, it turned out to be a nostalgic text about the learning Linux in the province, in the early 2000s, without the Internet and other things that are familiar to us now. And with a continuation in more civilized places, with the obligatory red eyes from night coding, jumping between Linux distributions and, ultimately, finding zen.

How I came to Linux

It all started very prosaically — my grandparents bought me my first computer and invited a friend, who was a programmer, to come over. He showed to me how to use my first PC — and told me about another operating system called "Linux" that was popular with programmers and hackers. This information was stored somewhere in the back of my mind. Back then, I didn't have internet access, except for a 56 kB/s modem at school, to which I could use every 1-2 weeks for a few hours. So I couldn't download the Linux distribution to record it on a CD, and I had no idea I could even download it from the Internet. I got the Windows distribution from that programmer, and occasionally I'd rent other discs. Usually, there were no Linux distributions there — only repacks of GTA, Half-Life and other golden classics.

Back then, I was using Windows XP and spending a lot of time playing Counter-Strike with bots and playing through various famous single-player games. I already knew how to program in Pascal and I had the Turbo Pascal IDE and compiler, which I copied to a floppy disk from the school computer. Of course, I ran it in full-screen mode because it looked cool! Like in movies about hackers, where people did some kind of magic by typing in incomprehensible text.

All this idyll would have continued, but a couple of years later I saw on the

shelf of a bookstore the book "Slackware/MOPSLinux for the user (with disk)".

Of course, I quickly and decisively persuaded my grandfather to buy it. Since

the computer was in my sole use, and I already knew how to reinstall Windows

and make backups (mods for CS 1.6 and my saves for GTA Vice City) — it was

time for some experiments! I had two CDs with Linux and Windows distributions,

seven hundred and fifty man pages, 150 sheets of a self-instruction book with

console commands and a lot of console utilities in /bin and /usr/bin, one 40

Gb hard drive, Xorg -configure which creates a non-working /etc/X11/xorg.conf,

and a text 80x25 console. Not that all is needed to become a cool hacker, but

once you start delving into the system internals, then follow your hobby to

the end. The only thing that bothered me was fdisk. There is nothing more

helpless, irresponsible and immoral in the world than a schoolchild using

fdisk to partition a hard drive. And I knew that pretty soon we would dive

into it.

At first I just read the book and learn the console commands. After Windows, it was awesome — you type some text, and the system answers you, just like in the movies. It doesn’t just draw an sandglass and it’s unclear what operating system is doing. After some time, I learned how to exit vim, manually configured the X server using man-pages and was able to install the Pascal compiler, with which I continued to learn how to programming using the ITMO University textbook. Then, I figured out how to compile programs from sources, which I received on disks from the Xakep magazine (Russian transliteration of the word "Hacker").

Of course, Windows XP still stayed in dual boot. The vast majority of the

software I used was for Windows. Support for DOC and XLS files in Linux was

bad in those days, and without GTA games I felt boring. And given the lack of

access to the Internet, I couldn’t figure out what else to do with Linux — KDE

2 3 was installed, I tried all the programs from the MOPSLinux disk, read the

chapters about DNS and the HTTP servers from the book to the holes, but didn’t

see the point of using them on localhost without the Internet.

Looking back, I can say that the knowledge and skills I gained became the basis that I still use today. It turns out that it is very useful to be alone with Linux, when you only have access to a book, man pages and source codes for the programs you want to install — there is no Internet or friends you can ask. This allows you to learn a lot about the system and develop skills in solving a variety of problems.x

Now, if some old, mammoth-shit, but very necessary legacy software refuses to

run, then that’s not my problem. I use ldd, make symlinks to the required

versions of libraries and read the logs to start the program anyway. If the

program crashes quietly, I'll use strace. If I hadn’t had these skills since

then, I can’t imagine how much time I would have spent at work and in pet

projects launching some not very "modern" and "right from the future"

software.

Red-eyed period

Around 2007, I entered ITMO University and moved to St. Petersburg. This is how I got access to huge (compared to what I had seen before) bookstores — House of Books on Nevsky prospekt and DVK (House of Military Books), which was neither a house, nor sells military books. Since by that time I had already been indoctrinated by Xakep magazine — the following were swept off the shelves:

- "Linux in the original" from the publishing house BHV

- "Developing Applications in a Linux Environment" from Williams Publishing (the photo of the MOPSLinux disk above is in the background of pages from this book)

- K&R "The C Programming Language".

Since at that time I had the Internet via dial-up, by the cards1, I rarely used it. Mainly I check de.ifmo.ru portal for students and download free as beer books from the Moshkov Library (Lib.Ru). When I tried to do something longer, the time on the card ran out, my Acorp Sprinter@56K hung up and I had to run to the post office again for a new card.

Therefore, again, as before, I sat with books, studied system calls, and wrote all sorts of simple programs to learn programming.

Unlimited Internet, which is familiar to us in the modern sense, appeared to me somewhere around 2009-2010 years. And then everything started to take off — I tortured the hard drive of my computer, installing various distributions there. Basically, I chose them according to the following principle: "Oh, what a beautiful desktop environment is in this distribution — let’s install it urgently!"

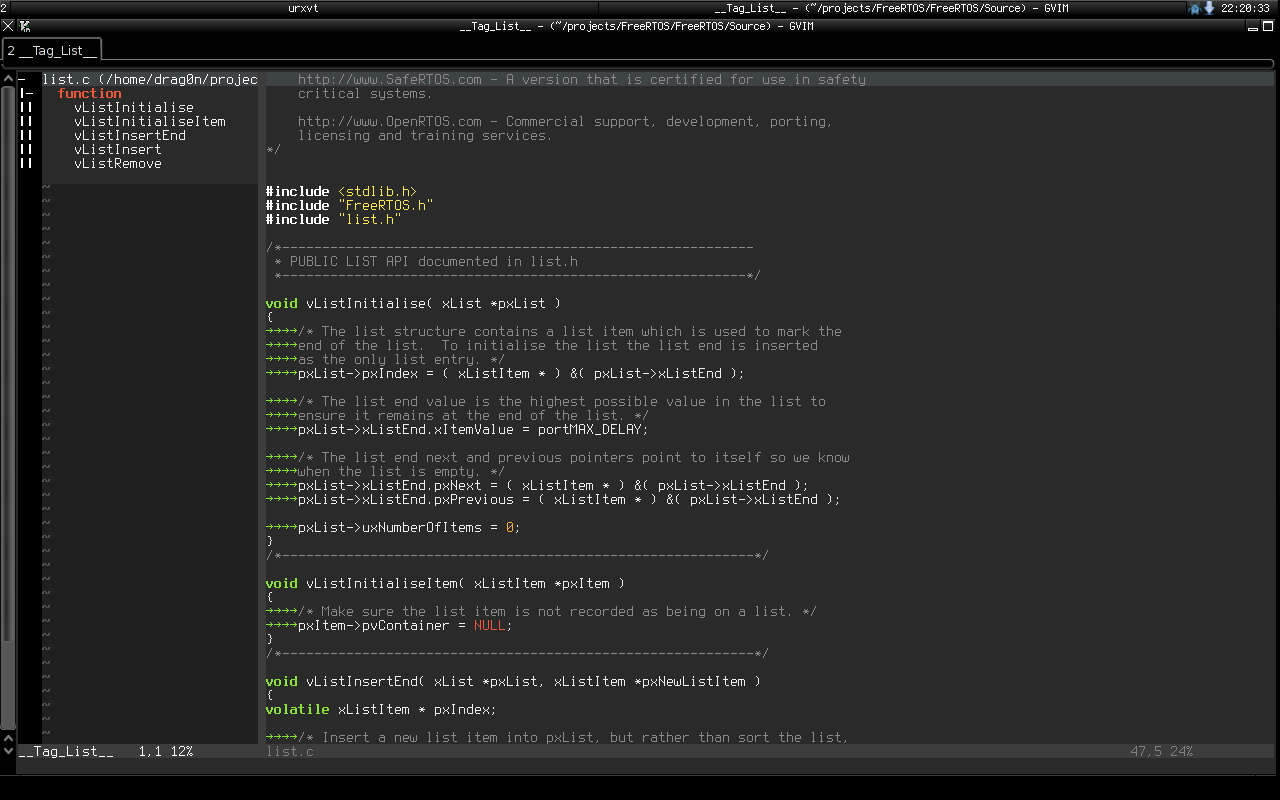

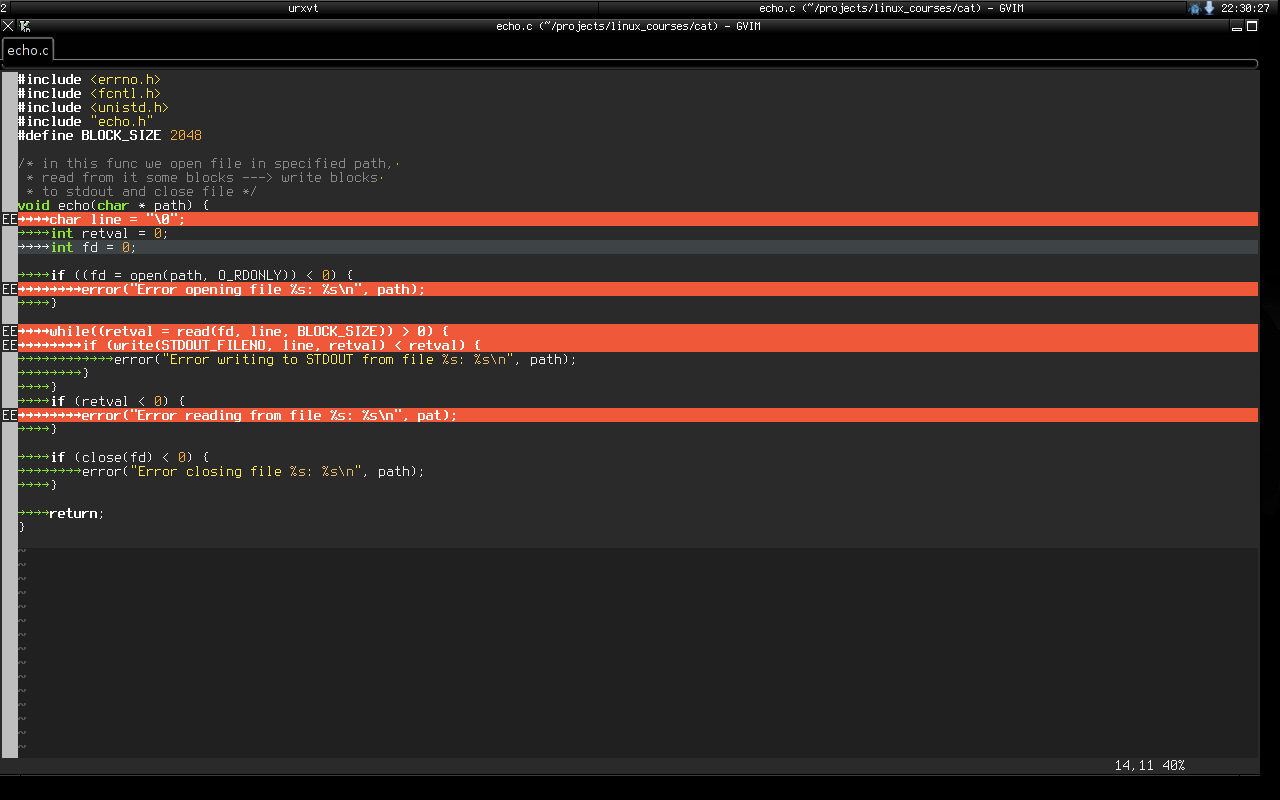

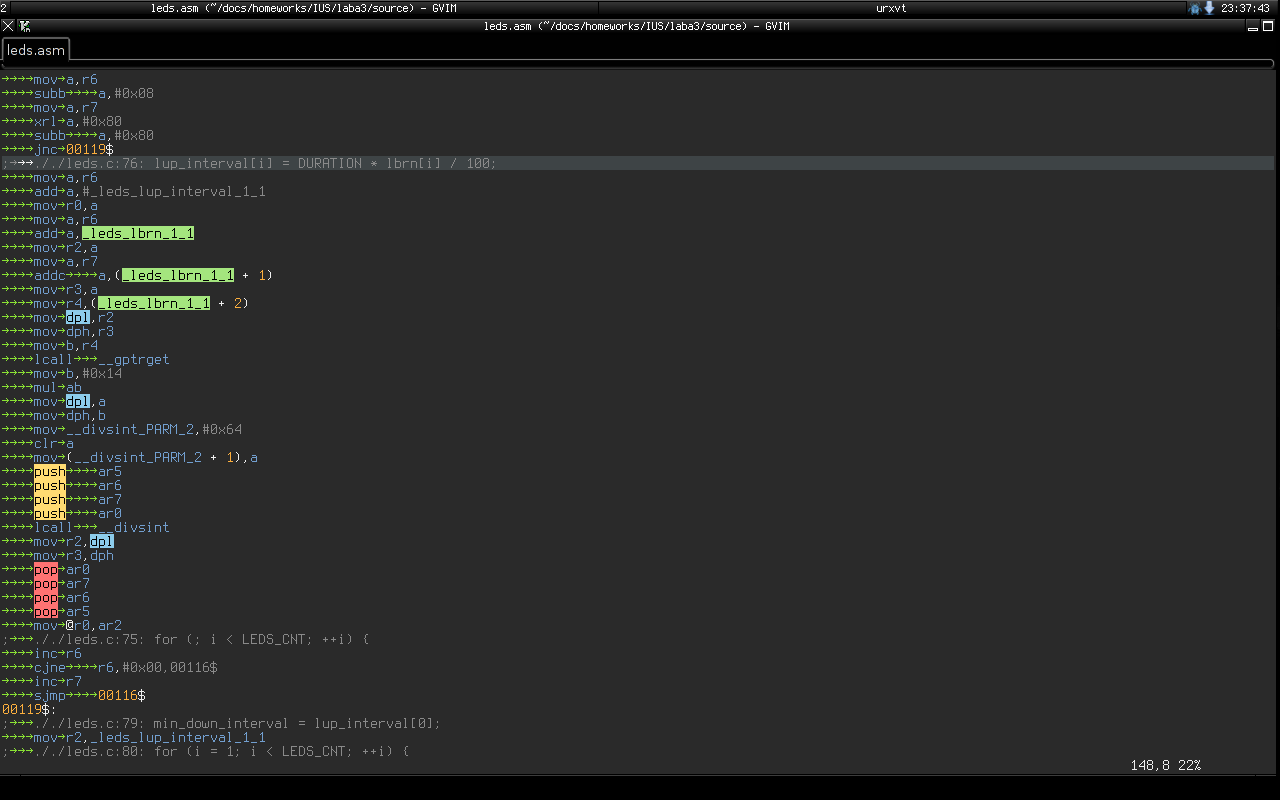

From that time I only have three screenshots left. Here I’m digging into the C code in GVim, covered with plugins (FluxBox window manager):

And here is some code in GNU Assembler:

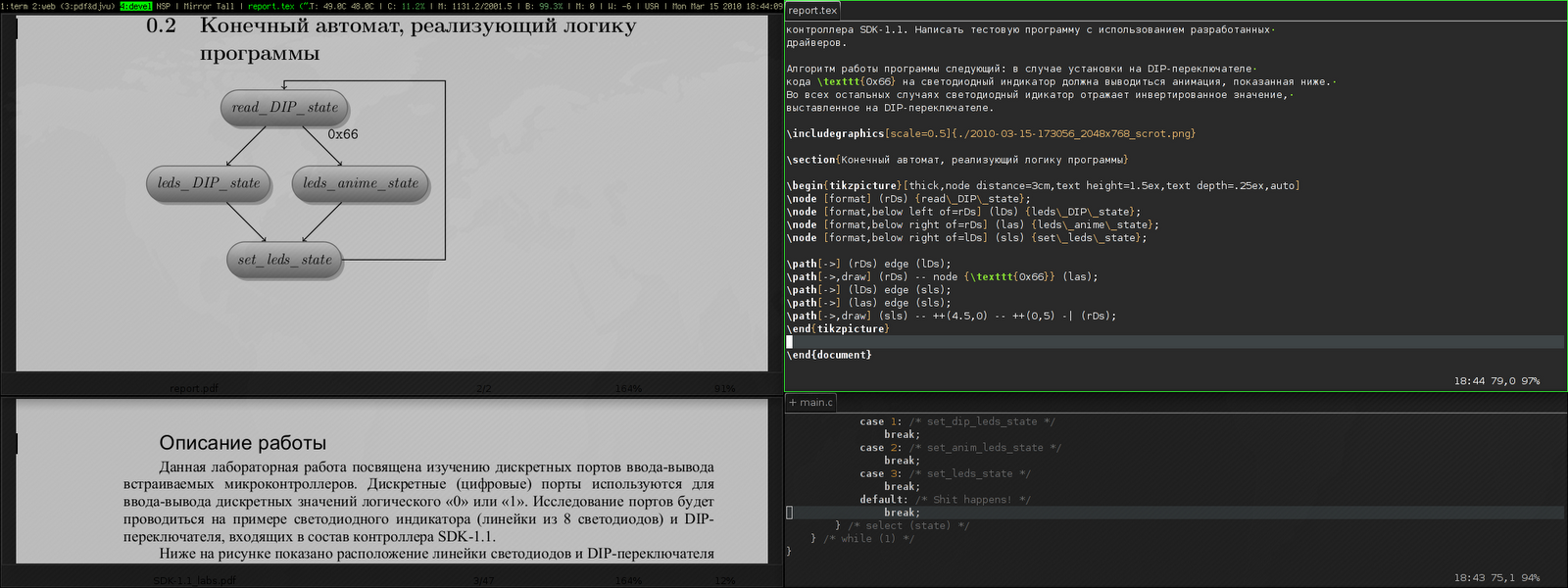

At the same time, I mastered LaTeX, tired of problems with printing student reports, when a file made in Open Office was printed crookedly in a bookstore near the university. And so I could finally write the report text in vim and get a beautiful PDF output that looks and prints the same everywhere.

Well, I continued to master system programming. One of the first programs I wrote is still in the SVN repository on SourceForge. This is jabsh (https://sourceforge.net/p/jabsh/code/HEAD/tree/) — something like a jabber remote shell. I didn’t have the opportunity to get a static IP address at that time, but I wanted to do something on my computer remotely. At that time, I had a Siemens C75 with the Bombus Jabber client installed, in which I chatted in all sorts of Linux conferences on jabber.ru when I didn’t have a computer at hand. And then the idea came to me to write a daemon that would connect to the Jabber server, wait for console commands from me, execute them and send the execution result in a return message.

This thing even worked and I used it until I got a static IP address. I even had a user from India for whom jabsh for some reasons did not work, and we send e-mails to each other for some time about this.

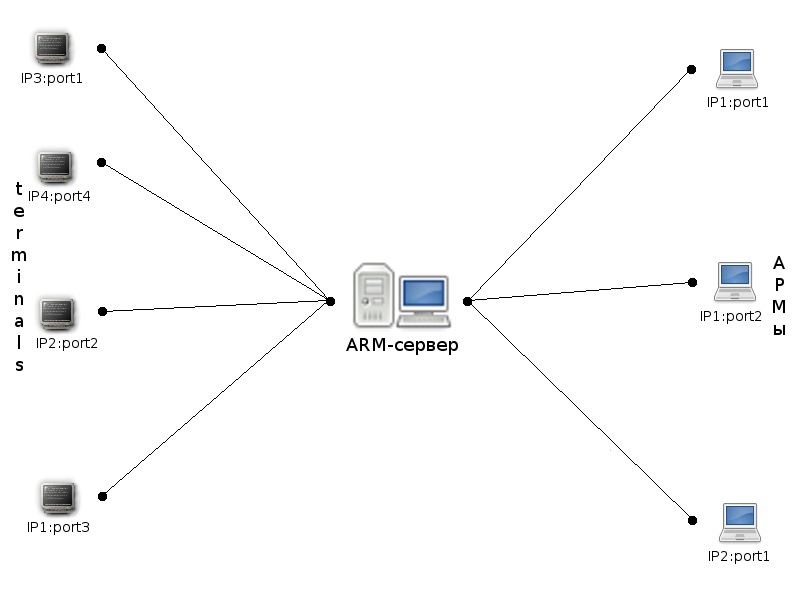

Another one of the programs from those times is a summer project from my future scientific supervisor — termprogs, for managing a set of "terminals" through "workstations", with a central server where the whole things are connected.

Just at this point, I was finishing reading William Stevens’ book "UNIX: Network Application Development" and could put all my system programming knowledge into practice.

Regexp 101 in ITMO University

Somewhere in my 2nd or 3rd year at the university, I started taking classes2 on system programming. At first we were taught to use the terminal and vim on thin clients from Sun Microsystems, with pot-bellied CRT monitors. During these classes, I do nothing for a whole semester — after all, I had already studied all this back in school. But then the fun began.

We spent half the semester studying regular expressions and the grep, sed and

awk. But regular expressions passed me by and I used grep at the level: "well,

if you pass it a string as a parameter, it will search for matches in the

file".

And here are furious tasks, kilometers of regexps and all that jazz. By the end of the semester, regular expressions were falling off my teeth. Looking back, I can now say that this regexp course is another unshakable pillar that I still use constantly. I can’t imagine how much time and efforts my knowledge of regular expressions saved me.

I still don’t understand where idea "if you solving a problem and decide to

use regular expressions, then now you have two problems" came from. My

experience at work and at home shows that if you need to somehow cleverly

parse a string using a regular expression, then you take sed or Java's Pattern

and Matcher — and parse the string. Then you test the resulting code, send it

to testers — and then it just works for years.

At the same time, I began to share my experience — write articles on welinux.ru, talking with other people on linuxforum.ru, and attend SPbLUG meetings. At one time I had a blog on WordPress, which I set up on some free VPS, which you could use as long as you did not go beyond the lower or upper limits on CPU and memory. That’s when I became addicted to writing all sorts of texts with amazing stories.

Linux and embedded-programming

Around 2011, I made a fateful decision — to go into embedded programming. At that time, this area of Computer Engineering seemed to me more interesting and romantic than "regular" programming. After all, there are no "simplifying" levels of abstraction here —you take and write code that works directly on the hardware! And then you debug the whole thing using blinking LEDs, debug printing via UART, an oscilloscope and other tools. And all the knowledge about bits, bytes, the internal structure of all kinds of EEPROM, SRAM and other things is used 24/7!

All relevant courses at the university included working with Windows — at that time the necessary development environments and compilers were mainly for this operating system. But, naturally, this did not stop me. For half of the software I used VirtualBox with Windows inside. For the second half, I was able to find the necessary native tools.

For training, we initially used special devices based on the MCS-51 family

microcontroller. If the code for them could be written in anything — I used

Vim/Emacs — then compiling and flashing the compiled binary into the device

was more complicated. For compilation, I used sdcc, but for firmware, a

special utility was needed — and m3p. It was written by one of the university

professors in ancient times on the C language. Fortunately, this utility was

written with cross-platform compatibility in mind, therefore, after a couple

of minor edits in the source code, it calmly did its job under Linux.

In those days, having begun to get tired of all sorts of "modern"

distributions, with their NetworkManagers, PsshPsshAudio PulseAudio, Avahi

Daemon and other "innovations" were breaking my user experience, developed

back in the days of Slackware — I came to Arch Linux. It was possible to

quickly install a basic system without the programs described above,

supplement it with only the software I needed, and calmly work and watch

memes.

Then I already began to develop a certain set of software, which I constantly used. By an understandable coincidence ("Russian" Slackware as the first Linux distribution and my love to use the console like a "hacker") it was mainly console software:

-

vim/emacs— for editing text and code. -

latex— for writing all sorts of complex documents, especially if they need to be printed or sent somewhere. Well, for drawing presentations, so as not to "get up twice". - Some kind of tiling WM — anyway, after a month of using some beautiful KDE or GNOME, I came to the conclusion that by default all my windows were expanded to full screen and scattered across the desktops, depending on the window name. And since you can’t see the difference, then why waste disk space on a heavy DE, if I can get everything I need in some xmonad or i3wm? Although, all sorts of beauty in the form of shadows, animations and transparency, which DE gives me, please the eyes for the first couple of weeks, but then the "wow effect" is expectedly lost.

- Well, and all sorts of other console utilities with which I could work with

or without consciousness:

grep,sed,git,make,cronand so on.

Since then, I had a repository with dotfiles, in which I dragged my configuration files for the above-described programs from system to system.

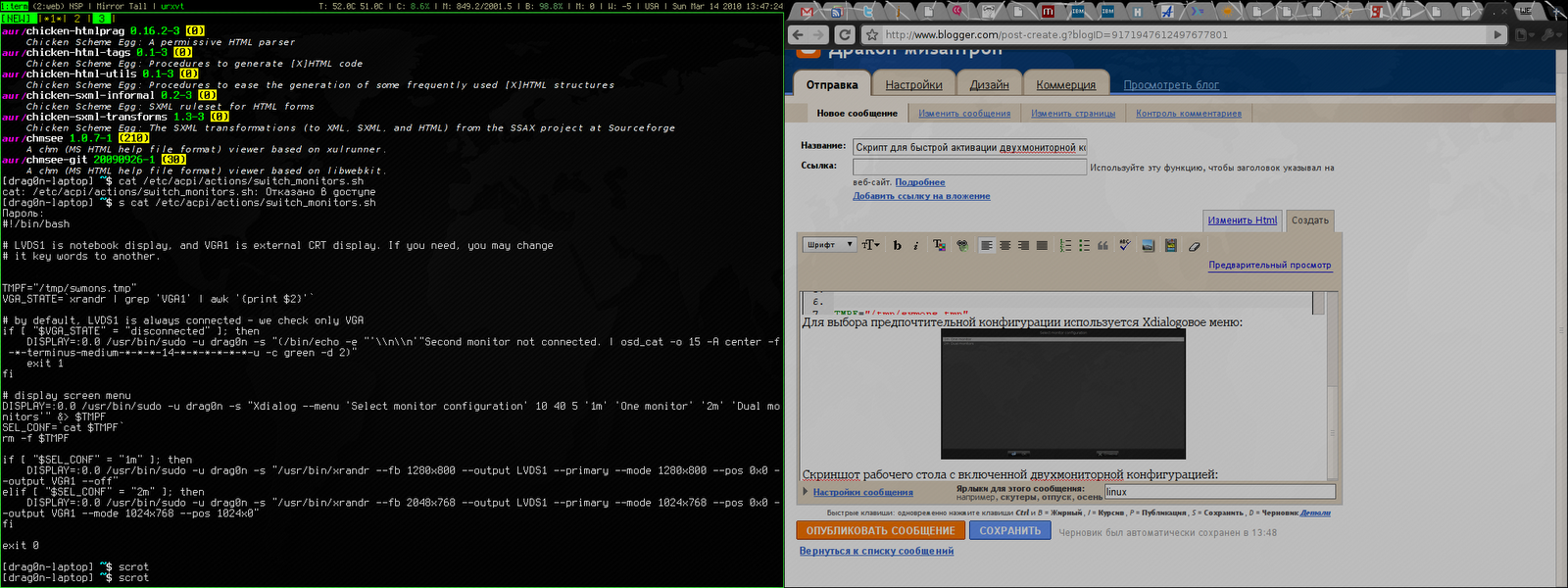

Here are some desktop screenshots from those days. Here is xmonad on two monitors - urxvt on the left, Chromium on the right:

And here the editing of the student's report. On the left is the final document in apvlv, and on the right is the TeX source code in GVim:

After that, I tried many times to switch to a usual software with a GUI or to all kinds of Web applications, but it just didn't work for me anymore. There weren't many ways to customize it for yourself. Some configuration options were extremly limited. Or software wasn't as fast as I'd desired. Or it was just inconvenient — the startup focus wasn't where I'm used to seeing it, or the main window displays information I wasn't used to seeing, and so on.

The final straw was the "redesign" of GMail. It slowed down even more and required more RAM than before. At this point I switched to mutt. Luckily, this thing is not the subject to the mOsT mOdErN dEsIgN trends and its appearance doesn't change from year to year. It works pretty quickly, alas, it launches not so quickly, even with caching. This is because I've had all my emails in maildirs since 2009 (about 47 thousand emails).

But the main thing with mutt is that it won't change in one "fine" day at the request of the left heel of the someone in the design department at Google.

In general, I've come to see Linux as more of a practical tool than a something "religious". There's no longer the same level of passion around which people wage wars over which Linux distribution is best. It started to become just a convenient and familiar operating system for me, one I only needed a little of:

- Do not do anything critical, such as software updates, without my knowledge.

- Just execut ethe programs, which are familiar to me.

- Stick to FHS3 and other standard things that I have learned since the days of Slackware — so that if some problem suddenly arises, I can quickly and calmly figure it out, understanding what is going on in the system.

- Do not impose on me a way to store my files — everything should be sorted into directories in the way that is convenient for me, without any tags or stars with the file rating. Or predefined directories.

At my first job, we used Windows 7 as the operating system for our office computers, which were used for embedded programming. When we needed Linux, we used Linux Mint, which worked great — no problems at all. I also maintained the servers, which ran some kind of RHEL. These tasks helped me become skilled at digging in internals of Web servers, database servers, and also in iptables, rsync and bash scripts.

At the time, I also had Linux Mint installed at home. I was generally indifferent to which Linux distribution I used. Anyway, I install the system in a minimal "console" configuration and then install the rest of the software I needed, according to the list from my repository with dotfiles. It seems like an ideal setup, doesn't it?

But then something strange started happening with Linux. Git renamed the

branch master to main, not for technical reasons, but because of some

political issues related to a single and distant country on the other side of

the globe. Luckily, I was able to avoid this unnecessary change, thanks to the

flexibility of the console software:

[init] defaultbranch = master

Then it became popular to replace the usual utilities like grep or ls with

their equivalents, which either print beautiful color output or work faster

(but on the volumes of data that I usually use, this did not speed things up

enough). I tried them out for a while, but I ended up going back to the usual

tools from coreutils. I didn't want to install into my system another supercat

that can highlight the source code in the output, but however, it is not in

the distribution repositories. So I need to go to GitHub and install it by

hand.

If I need the source code highlighted, I'll just open the file in a text

editor. Let cat simply print the contents of the file to stdout, as it has

done for decades!

Then, for some reason, developers started replacing ifconfig with iproute2. I

heard, what it was because of the need to work with IPv6. But in FreeBSD, as

far as I know, they simply added the necessary functionality to ifconfig and

people continue to use familiar and time-tested utility 🤷♂️.

The last straw for me was when they installed systemd everywhere instead of

System-V init or BSD-style init. I didn't like the way that non-alternative

pused systemd into Debian, and through it into the Linux Mint, which is what I

use. For about ten years now, it's been ingrained in me that at startup the

system launches ordinary shell scripts from /etc/init.d/ or /etc/rc.d/. I can

run them directly from the console or even edit them in any way I like to

understand why some tao-cosnaming or other daemon does not work the way I

want. And here we have something alienish thing, to which even the binary

registry has not yet been attached. The binary startup logs that can't be

viewed through less are already there. Plus, the unit files doesn't offer the

same flexibility as shell scripts. Plus, systemd diligently replacing all the

individual programs that were familiar to me, which always just did their job

and didn’t bother me over decades: grub, cron, agetty and so on.

At that moment (after, but not as a result) I left my job in embedded programming and went for a higher salary to the Java-enterprise, with bytecode, shell scripts, and a lot of regexes — everything I love.

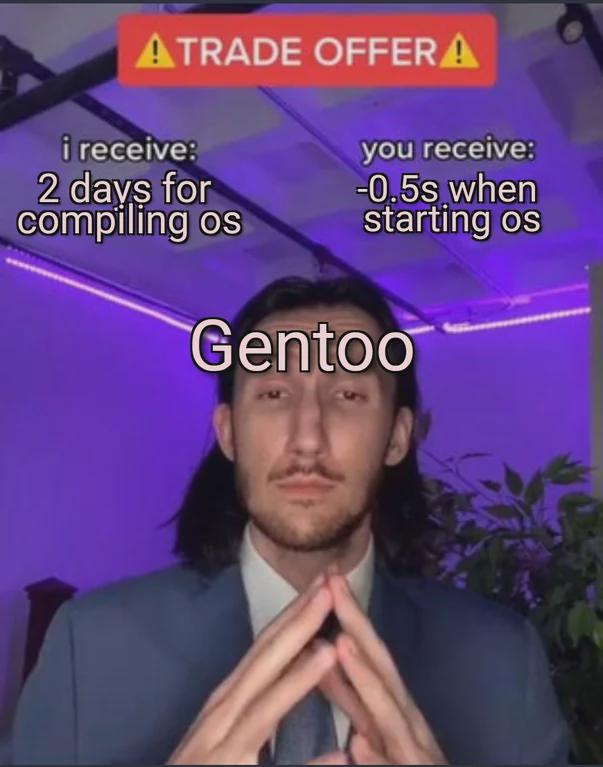

Well, trying to avoid systemd’s attack on my habits, I left Linux Mint for Gentoo.

I picked it because at the time, it was one of the few distributions that didn't use systemd. Instead, it had its own initialization system (OpenRC), which is very, very similar to the System V initialization system.

I wrote in /etc/portage/make.conf the next line:

USE="-systemd unicode -pulseaudio X alsa"

I haven’t experienced any grief since then. This system has been rock-solid for 5 years and it's still going strong. It has easily survived the kernel update from 4.19.23 to 6.1.57, and it just works. I run the update once a month, if I don’t forget, and that’s it. I think the reason it's so stable is that I use the really simple (like a digging stick) software, created in immemorial times. It doesn't have any "innovations" and it doesn't support simultaneous audio output to a 7.1 system, Bluetooth headphones in the next room, and over the network to tablet. Naturally, if everything is designed simply and clearly, then it won't break. There were only two times something broke after the update.

One day, the Midnight Commander developers renamed the configuration file

mc.ext to mc.ext.ini, to make it consistent with the names of other

configuration files. And I had to rename it myself.

The second issue I came across was that the person maintaining the binary package for Firefox forgot to link it with the libraries for ALSA4. As a result, there was no sound in the browser. I rolled back to the previous version of Firefox, went to the Gentoo bug tracker to create a new bug, but it was already there and people were actively commenting on it. A few more days later the package was put back together correctly and that was that.

What I expected and what I got

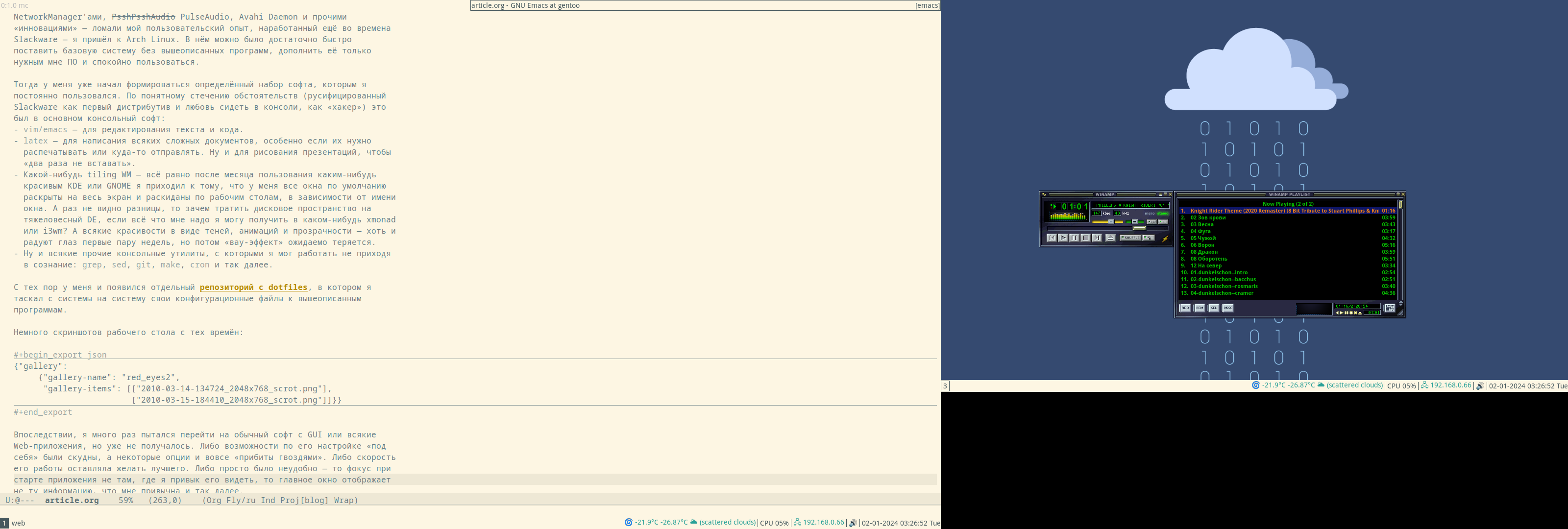

Audacious on the left

Audacious on the left

It's evident that I'm not quite at the level of a "cool Linux hacker, committing patches to the kernel instead of breakfast, lunch and dinner" (yet). But all those years of tinkering with console utilities paid off. I ended up with a pretty stable and simple system that I can use event without consciousness. In this system no one app will change it's interface by itself according to "new fashion trends".

In this system all my settings are stored in Git, so nothing will change without my knowledge. I can do whatever I want with just a couple of lines in the desired file and a several basic commands combined via pipe, for example:

- The plain-text accounting utility didn't allow me to use the "cash envelope" system I was used to. I used dialog, awk and sqlite3 to create a budgeting system on top of hledger that does everything I need.

-

I bought myself a Logitech Trackman Marble trackball, which has the "Forward" and "Back" buttons I don’t need. But there is no middle mouse button or scroll. And this is not a problem.

I create a file

/etc/X11/xorg.conf.d/50trackball.confwith the following lines:Section "InputClass" Identifier "Marble Mouse" MatchProduct "Logitech USB Trackball" Option "EmulateWheel" "true" Option "EmulateWheelButton" "9" Option "MiddleEmulation" "true" Option "ButtonMapping" "3 8 1 4 5 6 7 2 9" Option "XAxisMapping" "6 7" EndSectionThe "Back" button now works like the middle mouse button, and if hold down the "Forward" button, I can scroll the text in all directions with the ball. As I'd wanted, the trackball is now left-handed.

-

The new keyboard has Fn buttons for "My Computer", "Search", and "Browser", but no buttons for volume control? No problem! I use

xmodmapto reassign the button codes in the file it generates:keycode 152 = XF86AudioLowerVolume NoSymbol XF86AudioLowerVolume keycode 163 = XF86AudioRaiseVolume NoSymbol XF86AudioRaiseVolume keycode 180 = XF86AudioMute NoSymbol XF86AudioMute

So, for me, Linux is now just a system that runs the programs I'm used to — which, like a wall made of bricks, form my familiar user environment. The bastions — represented by Gentoo and Devuan5 — are currently protecting me from the overwhelming changes that aren't necessary for me and related problems. While the rest of the Linux world is changing the initialization systems, moving away from the X server and rewriting coreutils in Rust, I'm still using the same tools I've always used. I'm just easily read email and RSS feeds in mutt year after year.

When (if) these bastions fall, I’ll probably move to the monastery to

FreeBSD. Luckily, I've already got some experience using it as a regular

user. All my other software, like i3wm, emacs, Firefox, RawTherapee and so on,

also works there. The only big changes in my configuration that will have to

be made are to call gmake instead of make in some Makefiles, and to use more

correct she-bang #!/usr/bin/env bash in scripts, instead of the usual

#!/bin/bash. Unfortunately, I'll have to say goodbye to Docker, which isn't

available on FreeBSD, and the ability to work with LUKS crypto-containers. But

it’s better to lose them than all my familiar, configured with love

environment and my long-term habits.

My entire history of mastering Linux can be described as "hard to learn, hard to master". But over time, I developed all kinds of different habits that let me write texts, use the internet, and so on — literally "at my fingertips". That's why I’m not here advocating you immediately switch to i3wm or Emacs for the sake of pRoDuCtIvItY. Without the habits I've mentioned, it won't help. First of all, you have to want to learn, for example, Emacs, and be prepared for the fact that you will have to configure it for some time, and not perceive this time as "well, I need to set up a text editor instead of just opening it and writing text" — and then something will work out. I think all these articles about switching to Vim to be more productive in programming are misleading. Firstly, you'll spend time on vimtutor instead of programming. Secondly, there's not a strong connection between typing speed and programming. I can type at a speed of only 60-70 characters per minute, but this doesn't affect my productivity as a programmer. After all, I'm typing code on the keyboard at most 20-25% of the time. About 10-15% of the time is spent communicating with colleagues and on Zoom calls to figure out what's going on with this task or bug. The other 60-70% is spent reflecting in front of a notebook with a pen in hand, thinking: "how can I make a change correctly and quickly, so I don't waste a lot of time, either now or in the future?" So, vim won’t help with productivity here — it doesn't think for me in front of a piece of paper.

Third, let's be real. Right now, for a lot of languages, a big, complex IDE is still a better choice than Vim or Emacs. Even if you have an LSP server6 for your editor. For instance, Emacs' LSP for Java still doesn't work very well — it crashes on simple things, it doesn't update the context of changes in files as quickly as IDEA does, and requires some finesse to make it work with Lombok.

As a general rule, you can get a lot done in the GUI and it's the best place

for it. It's best to develop photographs in RawTherapee, edit images in GIMP,

view the site in Firefox, and so on. But there are lots of other actions you

can do right from the console. It's just matter of convenience. Some people

find it easier to select files to copy with the mouse in Nautilus, while

others prefer to use the cp ~/photos/{photo,video}_*.{jpeg,jpg,JPG,avi}

/media/BACKUP. It's great that Linux (for now) offers a choice for both people

who are used to a graphical interface and for those who prefer to communicate

with the machine by text.