When we think of “observability,” the first idea that probably comes to mind is “problems” or “troubleshooting” ( if you prefer the jargon). However, in this post, I want to present another view: observability is crucial for developing great software architectures.

My goal with this text is to answer three big questions:

- What is observability?

- What is great architecture?

- How can we ensure the existence of these architectures?

Monitoring vs. Observability

Let’s start at the beginning….

Monitoring

Monitoring allows teams to observe and understand the state of their APIs or even systems. Collecting predefined sets of metrics or logs is the fundamental idea behind monitoring, and it invokes a vision of obscurity, of being able to understand a system/software only from its inputs and outputs. Something represented in the image:

With this approach, we can define monitoring as in the example: Given that the API receives 1000 requests in format X, we expect to produce 1000 responses in format Y. As the definition makes clear, we are looking at predefined sets of information.

Observability

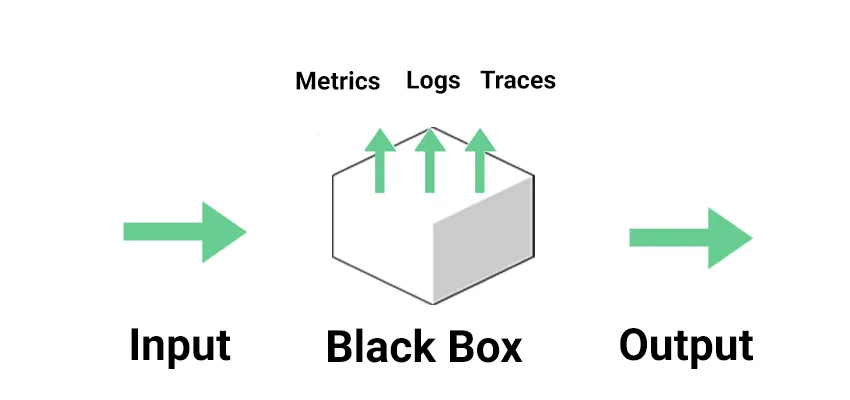

With observability, we can explore properties and patterns we have not defined in advance. Observability invokes a feeling of transparency, a form of exploration based on metrics the system exposes. The classic representation of observability is something like this:

Thanks to the signals the application generates, we no longer see our system as an opaque box but can see “its interior.”

In the image, we can see the so-called “three classic pillars of observability”:

- Metrics: Numerical measurements collected and tracked over time.

- Logs: A detailed transcript of system behavior

- Traces: a route of interactions between components, along with an associated context;

But some recent posts expand the concept by bringing new signs:

- Events: snapshots of significant state changes;

- Profiles: a method for dynamically inspecting the behavior and performance of application code at runtime;

- Exceptions are a specialized form of structured logs. This signal is not so common in documentation; it is often considered just a Log version. But I thought it was interesting to keep it in this document because it may make sense for some scenarios.

AWS Well-Architected Framework

If we ask different people, “What defines a good architecture?” We should get different answers as well. This is because there are different views and definitions for this answer. In this post, I will adopt one of the possibilities: the framework developed by AWS to define applications that make better use of Cloud Native concepts in their architectures.

The framework defines some pillars:

- Operational excellence: focuses on the execution and monitoring of systems and the continuous improvement of processes and procedures

- Security: focuses on protecting information and systems

- Reliability: focuses on workloads performing their intended functions and quickly recovering from failures to meet demands

- Performance efficiency: focuses on structured and simplified allocation of IT and computing resources

- Cost optimization: focuses on avoiding unnecessary costs

- Sustainability: Focuses on minimizing the environmental impacts of running cloud workloads

Although developed by AWS, the concepts described can be applied to applications in any environment, even on-premise.

But where does observability fit into this framework? In my view, observability is at the center of most of these pillars:

To detail what I understand about this interconnection, I created a table correlating the pillars of observability and those of the AWS framework:

For example, metrics, traces, and profiles are necessary to ensure the Performance Efficiency pillar. Similarly, the Cost Optimization pillar can be observed using events and metrics.

And how to ensure great architecture?

To answer this question, I suggest two complementary approaches.

Fitness Functions

The term was first coined in the book Building Evolutionary Architectures and used again in Software Architecture: The Hard Parts: Modern Trade-Off Analyses for Distributed Architectures, and its definition states that:

“They describe how close an architecture is to achieving an architectural goal. During test-driven development, we write tests to verify that features conform to desired business outcomes; with fitness function-driven development, we also write tests that measure a system’s alignment with architectural goals.”

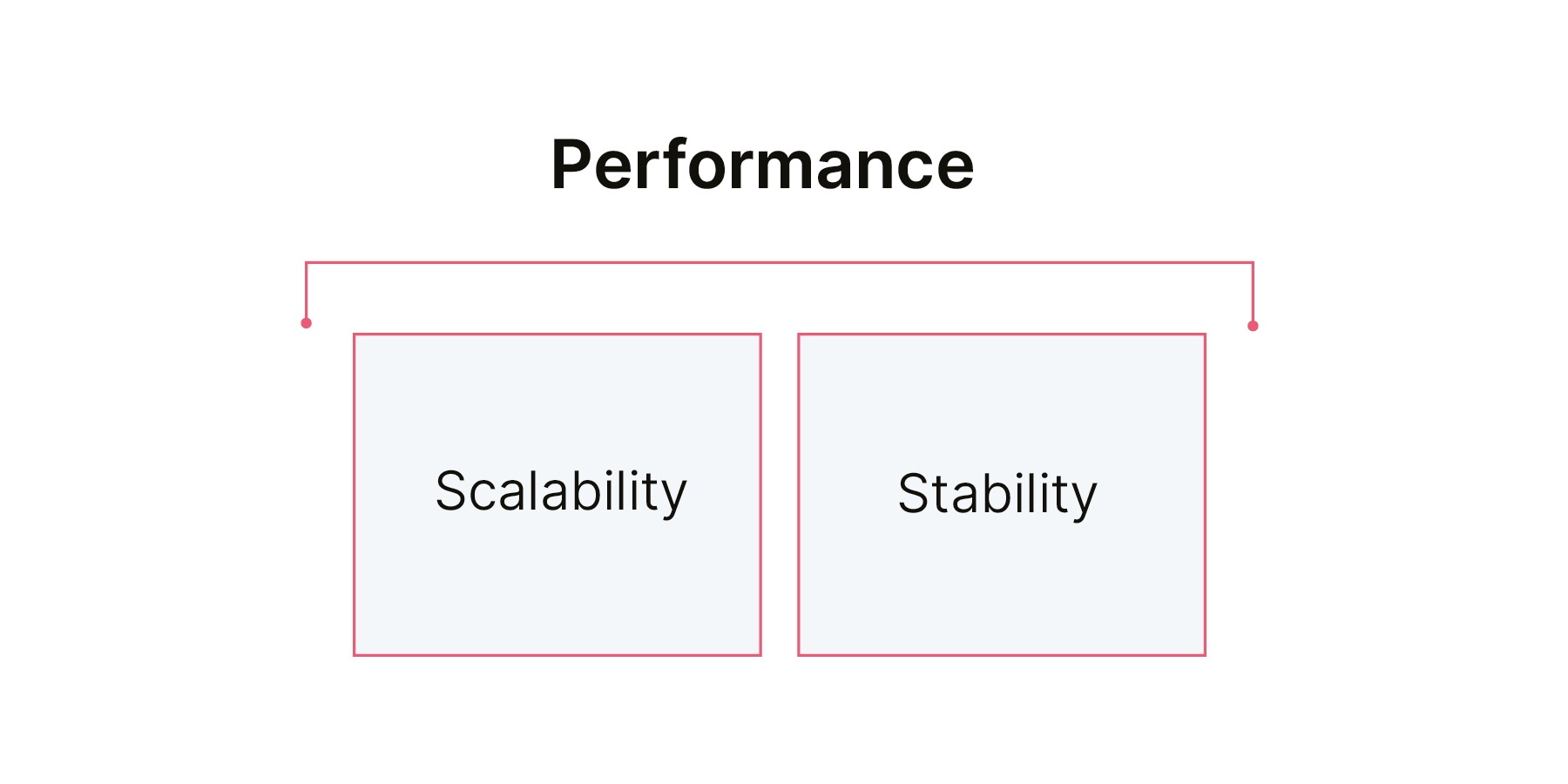

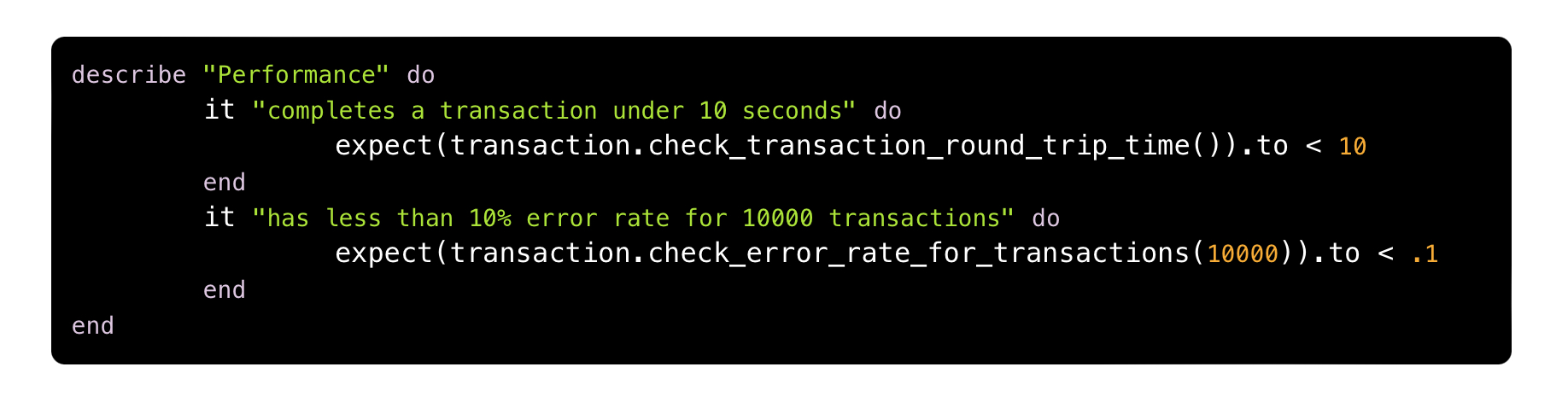

So, let’s imagine a fitness function to validate the performance of an architecture:

We could describe a possible pseudo-code for this test as follows:

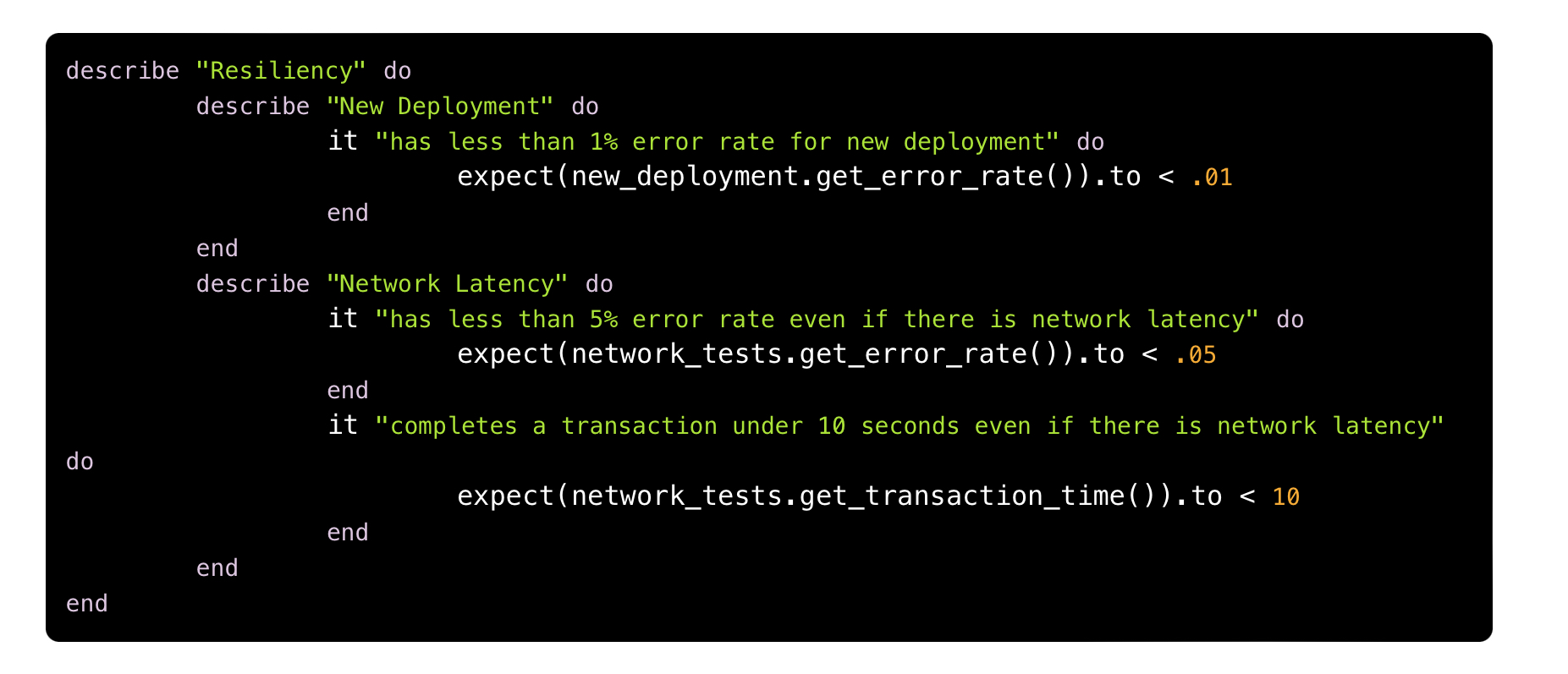

Another example would be validating the resilience requirement:

Whose pseudo-code would be:

In both examples, we were only able to perform validations thanks to the use of metrics (transaction.check_error_rate_for_transaction and network_tests.get_transaction_time, to name two), one of the classic pillars of observability.

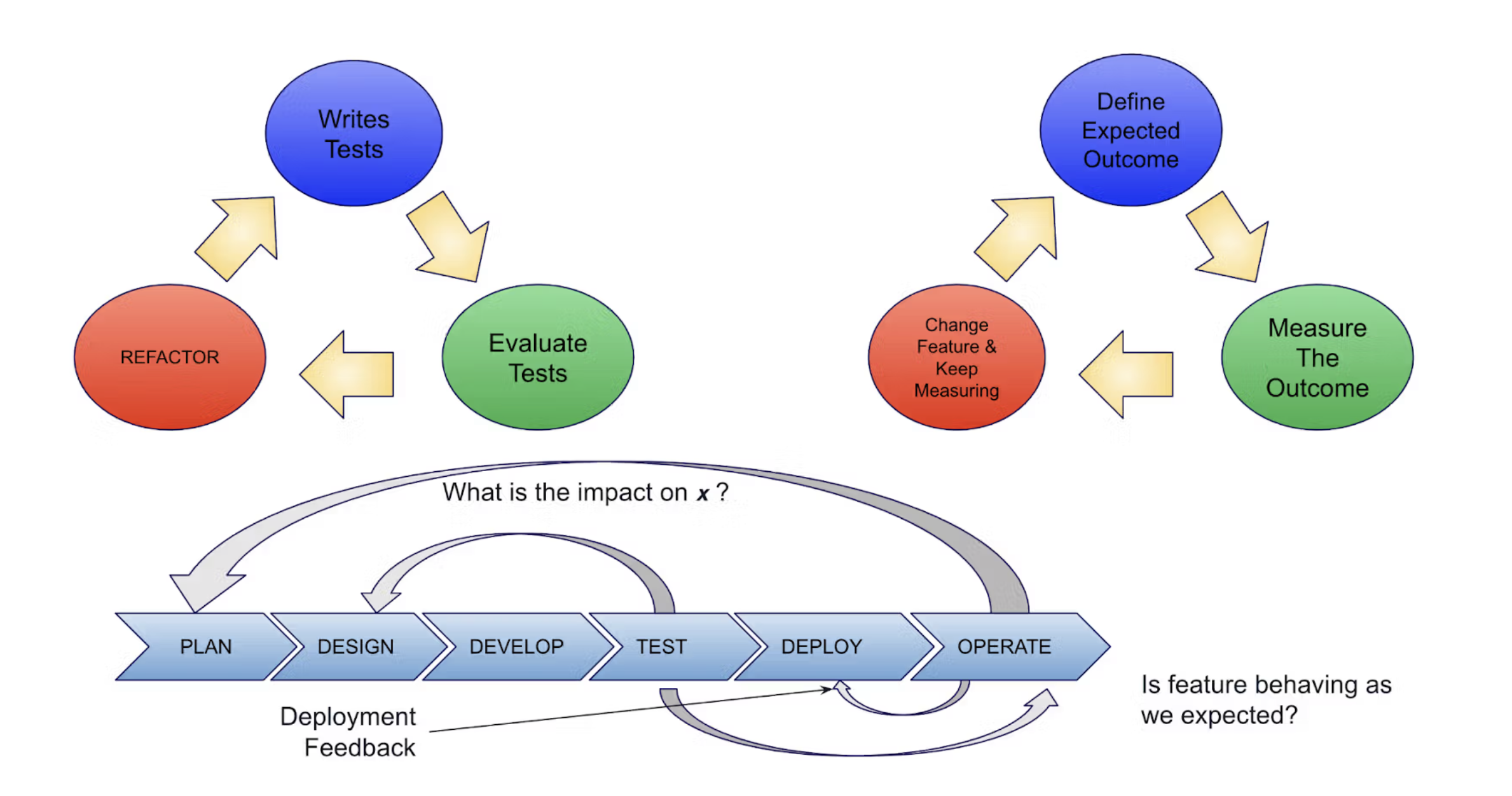

Observability-driven development

The other way to ensure that our architecture grows healthily is by using the concept of ODD (Observability-driven development), which we can describe as:

ODD is a “shift left” of everything related to observability to the early stages of development.

One behavior I’ve seen repeated in some projects is that the team does the implementation and, in the last stages (usually when problems start to be identified in QA environments or even in prod), starts to instrument the application, including logs, metrics, and traces. ODD proposes to bring discussions about observability to the early stages of the development cycle.

ODD has similarities with another famous acronym, TDD (Test-driven development), with the main differences being:

- TDD: Emphasizes writing test cases before writing code to improve quality and design

- ODD: emphasizes writing code with the intent of declaring the outputs and specification limits necessary to infer the internal state of the system and process, both at the component level and as a complete system

The following diagram puts the two techniques into perspective:

While TDD created a feedback loop between testing and design, ODD expands feedback loops, ensuring features behave as expected, improving deployment processes, and providing feedback for planning.

Conclusion

Recapping the first paragraphs of this text, let’s review the three questions I proposed and their answers:

- What is observability? Metrics, Logs, Traces, and other pillars

- What is a great architecture? I brought the AWS Well-Architected Framework as one of the possible ways of defining it

- How can we ensure the existence of these architectures? I presented two ways, using fitness functions and ODD

I also hope to have brought the perspective that observability goes beyond a series of tools and concepts to be used in troubleshooting moments and is also something we can improve to develop efficient software architectures.

Links

- Cell-Based Architectures: How to Build Scalable and Resilient Systems

- Fitness function-driven development

- Building Evolutionary Architectures

- Software Architecture: The Hard Parts: Modern Trade-Off Analyses for Distributed Architectures

- TEMPLE: Six Pillars of Observability

- AWS Well-Architected

- How observability-driven development creates elite performers