9 July 2025 by Richard

What hope is there for science reform, if we can’t agree on what to reform? Right now, principles are more important than practices.

Science has always been a bit shit. In 1789, the historian (and minor playwright) Friedrich Schiller complained about the problem of “bread scholars” (Brotgelehrte) who resented rigor and reform, focusing instead only on career advancement and job security [link]. He enjoined his junior colleagues to resist careerist incentives and focus instead on the intrinsic rewards of seeking and accumulating knowledge.

These days complaints about bread scholars persist. You might have heard that academia still has a reputation for sloppy, self-interested, and sometimes fraudulent output. People talk about a “replication crisis,” but it’s hardly new.

But the scholarly landscape is very different than it was in 1789. Pre-publication peer review didn’t exist back then—that didn’t begin until the mid-1900s [link]. Impact factor had never once been calculated (or rather negotiated). Press releases and grant overhead didn’t exist. What remains the same is that career incentives dominate intrinsic incentives. This doesn’t mean that science doesn’t work—it’s always been a bit shit, remember. But it could work better, if only we could figure out how.

All of this is old, but it is recently in the news, because the current government in the United States issued a memorandum on “Restoring Gold Standard Science” [link]. This memo is pretty vague, but it uses language from the open science movement, stating that “Gold Standard Science” is (i) reproducible; (ii) transparent; (iii) communicative of error and uncertainty; (iv) collaborative and interdisciplinary; (v) skeptical of its findings and assumptions; (vi) structured for falsifiability of hypotheses; (vii) subject to unbiased peer review; (viii) accepting of negative results as positive outcomes; and (ix) without conflicts of interest. Although these things sound nice to most people, most people in my social network reacted very negatively to this memo [link]. Many researchers seem to think the memo is vague enough that it will allow political appointees to interfere with research.

I want to make a different point: We don’t know how to achieve any of those goals, nor is there any broad consensus that the problems with research will be fixed by achieving them.

So where do we go from here? I have some ideas. But I am not sure you’ll like them, because they don’t promise much.

Bad Science, But Open

The last 20 years has seen the growth of the open access and open science movements. These movements are vaguely defined, but aim in general for increased public access to research results and processes. Open access has succeeding in making more and more articles free to read, but the quality of scientific publishing is no better than before, and arguably reduced. Open data and code have not been nearly as successful.

The Open Science Bandwagon [UNESCO Open Science Salad – source]

I don’t think any of these “open” initiatives—access, data, code, preregistration—will do much by itself to make research more reliable.

Open access was never supposed to make papers better, just easier to access. So I won’t saddle it with unreasonable expectations. But it has anyway been captured by for-profit publishers who still don’t provide any “value added”. What are we paying for exactly? I hope it’s not peer review, because we do that too. If access were the problem, we could just put our papers online—preprints are in fact published.

Open data and materials are not going to magically make research higher quality, without some foundation to help people make better data and materials. Research can be open and reproducible and still completely and obviously wrong.

Openness does not fix systemic problems in the lack of professional training and lack of professionalism in scientific research. Every day, researchers invent ad hoc data analysis of badly curated data. The results of such plans are both misleading and replicable. The biggest problems with research are not lack of access to data and code, but rather that so many researchers have little training in data management and cannot justify their data processing procedures or conclusions in any transparent and logical way. Worse, their procedures are invalid within any statistical paradigm, such as comparison of p-values [link] or using predictive criteria (like AIC) to make causal claims [link].

Nature magazine is still publishing papers that filter for large effects and then run countless significance tests. And when this is pointed out, the editors treat it like an ordinary difference of opinion [link]. Absurd ad hoc analysis pipelines are justified solely by their results, not by their logic. And once they are published, open code just makes things worse, because other researchers use the code to publish more rubbish.

It’s one of open science’s failure modes: Sharing illogical methods that produce exciting false results just makes it easier for others to publish false results. It’s the ongoing natural selection of bad science [link], now with enhanced transmission and rate of evolution.

It feels underwhelming to write this stuff, because it is so well known. And yet so much of the open science movement has been focused on misconduct and questionable-research-practices (like p-hacking), instead of research procedures like data management and justification of modeling choices. Open data and code and preregistration help us find problems in the literature. But they don’t prevent them. Preregistered junk is still junk, but somehow it smells better because it is open science.

The Open Science Pyramid is a Tomb

I talk to lots of junior colleagues about this stuff. They want a lot of different things. But mostly they want more senior academics to recognize and talk about these problems. It’s not like it’s a secret that there are replication and reliability problems at the highest levels of research. It’s that the most successful academics talk about it the least. Recognition would help not only with morale, but also with momentum to get things done.

Supposing we could talk about it, and could build some momentum, what might we do?

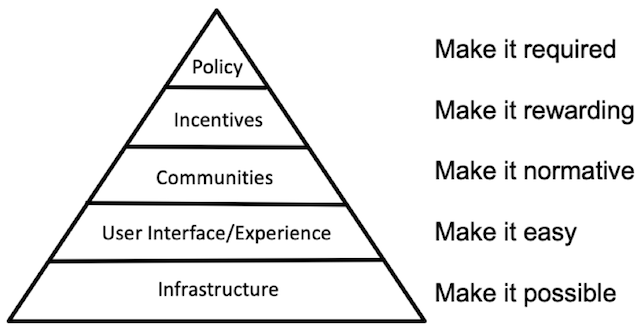

Reform is hard partly because we have to reform everything at once—what good is it to train students to do better science when better science won’t be rewarded? Are we just setting them up to exit academia? The Center for Open Science has since 2013 been active in building tools for more transparent and reliable research. It has a strong social psychology flavor, so the things they emphasize don’t always appeal to me. But they take action and strategize at both micro and macro levels. One image they share is a strategic diagram for reforming the culture of research, the Open Science Pyramid [link].

The pyramids of ancient Egypt were famously tombs [link]. And this pyramid can feel like a tomb as well, because it makes it clear how hard change can be. This is where open science is buried.

What I like about this pyramid is the recognition that it makes little sense to incentivize or mandate (top) some practice until it is possible for researchers to do it (bottom). Likewise, we can train people to manage data, but unless there are career rewards or requirements for doing so, it won’t easily spread. We can and probably must work at all of these levels at the same time.

What I dislike it the (accidental) implication that we know already what “it” is or that it is the same across levels. The “it” at the different levels is not the same abstraction. Infrastructure (bottom) is more precise and behavior than rewards (top). Rewards end up incentivizing all manner of new behavior that we don’t anticipate. And since we don’t really know exactly what “it” is yet, we probably don’t want to incentivize or reward specific practices.

I’m going to run from bottom to top and expand on this, focusing on my own scientific society, the Max Planck Society. The points are make are very idiosyncratic. And incomplete. But they illustrate the reforms at different levels and the obstacles as well.

Making it possible

What infrastructure do researchers want, in order to do better science? The science reform community that I interact with is not focused on openness (access and participation). It’s focused on systematic reform of scholarship, from training to funding to dissemination.

I have spent the last few years talking to open science advocates in the Max Planck Society, in the German university system, in organizations in other countries, and in international societies. Open access is not a priority in these communities. And while open data and materials are valued, I hear that the data and materials they see opened are often too low quality to be useful or even intelligible. We often say that making data and code open will force us to perform better data management and to write better code. But if we produced better data and code internally, we would get better research without openness. And since so much data can never be open for ethical reasons, openness cannot be a general incentive.

The priorities are training for research design, data management, and statistical modeling. Junior scientists tell me they feel too often unsupported in basic scientific skills. Workshops for grant writing are commonplace. Workshops for doing research are rare. Methods training is too often just something one is expected to soak up from colleagues and the published literature. PhD students have almost zero statistical training, and even less training in how to connect statistical analysis to theory.

I don’t care if you preregister your study. I care that you can justify your study, using some kind of logic that bridges a formal theory and a data analysis plan. Very few researchers get the training to do this.

The Max Planck Society has the resources to sponsor training (through Planck Academy for example). Curricula like Software and Data Carpentry already exist.

Still at the current time, many PhD students tell me they are often the only person at their institute interested in these basic professional skills. Everyone else is racing as fast as possible to publish a Nature paper and get their next short-term contract. There’s no time to learn how to do science! This is a theme that I’ll return to later.

Making it easy

Over time, technology makes science easier. And there is still a lot of room for technology to help us with broader research workflow, from theory development to error checking to reporting.

It used to be very hard to perform a linear regression. Now, there are fast and accurate mathematics libraries that can invert large regression matrices. You don’t need to do a sum-of-squares even. This is a good thing. It allows researchers to focus instead on the structural design of models and how they relate to theory.

In the future, we should have software assistance that helps us integrate theoretical models with research designs, statistical models, diagnostics, and result summaries. A change to the data should flow through this workflow and tell us which elements need to be updated. There is already software like Targets [link] that does a lot of this. But generative models and logics (cacluli) that justify connections between causal and statistical models are completely missing. There’s no reason that software couldn’t advise researchers on which assumptions are necessary (within a given causal modeling framework) to justify a statistical procedure for a specific causal estimand. I have in mind something analogous to the proof networks one builds in a language like Lean4 [link].

All of this can be done without software assitance. But students need support to learn this stuff quickly and to implement it reliably. And widespread software support helps researchers step into new teams and quickly integrate their contributions and expertise. Science is distributed teamwork, these days.

I like the analogy of professional training in software engineering. Every software engineer needs to know some basic teamwork skills, like version control and testing infrastructure. There is no similar, widespread set of professional tools in research coding. But there should be. Too much science is like amateur software development.

I don’t mean to argue that all research needs to be slow and fully documented. When we are just starting in a new area, it’s chaos. But at some point, by the time results are reported, the workflow needs to be professionalized. Research is not a hobby. It’s a job.

Making it normative and rewarding

In principle, the Max Planck Society gives institutes complete freedom to reward scientists for doing slow, reliable research. The entire idea of the society is to give researchers the environment they need to take risks and build long-term contributions that are too difficult in other settings. We don’t have to play the game of chasing big-if-true Nature papers.

But most institutes chase Nature papers anyway. Partly this is because PhD students and post-docs cannot make careers at a Max Planck Institute. German employment law makes it impossible for most. Most will either take a position at a university or exit academia (which is a valid choice, and a choice that we should be training students for). So an institute plays to the outside environment, not the inside environment. And this sometimes ends up undermining research quality for everyone, including those with permanent contracts.

The society does have some top-down tools, but not many. The funds provided to PhD programs can come with requirements. They already do. But they don’t require basic training in, for example, research data management. Future renewals could fold in such requirements.

Institutes are also externally reviewed every 3 years or so. Review commissions could be instructed to assess and evaluate steps taken to train and conduct more transparent and sustainable research. For example. Those would be my own goals. But as I said before, we don’t have a consensus, and defining what “transparent” and “sustainable” mean in each institute will not always be easy. But I think the external commissions could do it, given their domain expertise.

The biggest problem is the leadership of the institutes, the directors, people like me. Most of us got appointed by being successful in a system that lacks the reforms that are needed. And the job encourages a kind of competitive narcissism that views complaints about the system as weakness. Why would you trust us to implement reform?

The good news is that a lot of directors are going to retire in the next 10 years. More than 100 of them. If hiring is done right, a lot of change can be accomplished. But we’ll have to be less focused on hiring people based upon how many Nature papers they’ve published. Instead we’ll need to hear that they have a persuasive vision for how to improve the conduct of research in their field. No more Brotgelehrte with high h-indices, please.

I think the biggest thing we could do to improve research is to stop rewarding individuals but instead reward teams. Science is done in teams with division of labor. But the whole scholarly career track still pretends that only the mythical Principle Investigator deserves a permanent job and recognition for their contributions. This generates competitive incentives that undermine research. I’ve spoken about this before.

All of the above implies that we also have to be patient. Research culture will change on demographic timescales. But we can be doing things now to create the evolutionary incentives so that the change is in a positive direction. But there will be no fast change. And this is also an obstacle, because a scientific society wants to make its mark. It wants to negotatiate deals and announce programs and solve problems with money.

That’s not how this is going to work. The rewards are postponed until after many of us are retired. But that’s no excuse for inaction.

Making it required

I am skeptical that we can or should strictly require any specific reform within the Max Planck Society. It’s not only that we don’t yet know what to require. Rather specific targets tend to create perverse incentives. If we require preregistration, for example, people will learn how to game preregistration. I think they already have! If we require open data and code, people will share incomplete and unusable materials. I think they already do!

But probably there will eventually, possibly soon, be government regulation around science reform. Germany is rumbling about some national research data strategy. And while I haven’t mentioned publication so much, it’s foreseeable that nations will stop transfering public money to private publishers and start requiring that all research be deposited in central repositories.

So we might not get to choose what we require. The politics will do it for us. And the slower we are in showing a wiser, more scientific spirit of reform, possibly the more likely we will get badly designed, externally-imposed requirements and review. Like that “Gold Standard” memo.

Anyway, I am currently against strict requirements on the conduct of research or how it is reported, beyond the general nomative standards of honesty and ethical conduct. I just don’t believe that meta-science is a mature enough field. Maybe it never will be.

Justified plausible belief

What if I told you that, if we try very hard and agree to make our science comprehensible—rather than merely transparent—we might not systematically mislead ourselves? There’s a chance. That’s all I’m promising.

In the context of the Max Planck Society, the best I hope for right now is leadership to agree upon a set of broad principles and that every institute and scholar be asked to justify their research in light of those principles. We do not want to prescribe procedures, because we don’t know what works! But if we can stop rewarding people for output and instead reward people for good process, as judged by their own arguments that process fulfills the sound scientific principles, then we can maybe evolve towards a better state.

The principles that I advocate are:

Comprehensibility of research. This is not transparency nor openness. What I mean is research has sufficient documentation and justification to reduce error and empower others to make up their own minds about its value. Research should be intelligible. Access is not sufficient. Research can be replicable without being reasonable or correct. Materials and data can be open without being intelligible, and they can be partly closed while still being comprehensible. The rise of AI reinforces the need for comprehensibility, because “I asked the chatbot” is not comprehensible. But for sure AI will be a part of scientific workflow now and into the future. But the researcher must be responsible, not the bot.

Sustainability of research. This means ensuring the future usability of research products and the future integrity of publicly-funded research so that cumulative scholarship is possible. Proprietary software and data formats threaten the future impact and interoperability of research products. Documentation and meta-data protect investments in knowledge production and catalyze future research. Sustainability and comprehensibility are synergistic, for individuals, teams, and the public.

I’m personally putting a lot of work into comprehensibility lately, working on a formal meta-scientific framework for scientific workflow, a framework that aims to make good science easier and more sustainable. But that’s a topic for another time.