Open-access content —

Fri 7 Mar 2025 — updated 17 Mar 2025

Image Credit | Shutterstock

In our last issue, we looked at some of the most hazardous jobs in the engineering sector. But one stood out as being worthy of an article in its own right – saturation diving for the offshore oil and gas industry.

As a light shines from the approaching remotely operated vehicle (ROV), his limbs twitch and his arms reach out weakly as if grasping for help. His gas has long gone. His pipe snapped more than half an hour earlier and no one was expecting to find him, let alone alive. But the wait is haunting. The only ship that can deliver a diver to rescue him in time is struggling to regain control in stormy seas above. In the meantime, the helpless and horrified crew can only watch.

This was back in 2012, and saturation diver Chris Lemons has no recollection of the encounter, though he’s talked about it many times since. “I think the people who had to witness it suffered more. Some [on the boat] decided never to work with divers again.”

Saturation diving is a small world and everyone in it has heard of Lemons’ story. These divers breathe a pressurised mix of gases and remain under water for up to 28 days in order to work at depth, mostly in the oil and gas industry.

When he was first found by the ROV, Lemons was unconscious and involuntarily twitching. The accident should never have occurred, but when asked if it could happen again, he hesitates. Today, there are back-ups and contingencies to avoid a single point of failure. “But then all three computers on the bridge went down in one go,” he says.

Support ships are now vast, the instrumentation ever more sophisticated. “With Chris, the vessel’s dynamic positioning system lost control,” says Neil Gordon, head of industry body Global Underwater Hub. Putting a saturation diver in the deep sea is akin to sending an astronaut to the Moon, he says – a sizeable team is behind any mission and any failure can be catastrophic. “But our safety record in the UK is excellent,” he says. Pioneered by the US Navy, saturation diving was developed in the North Sea’s oil and gas fields during the 1970s and has been used ever since. “We are the world-leading country for this diving and there hasn’t been a fatality for many, many years.”

The industry is now highly regulated as learning and safety techniques have been developed over the decades – Image Credit | Shutterstock

Seconds from disaster

Lemons fell unconscious after exhausting his emergency gas supply. Earlier, the dive ship supporting him and his fellow divers 200km east of Aberdeen had begun drifting at pace in the 35 knots of wind and heavy seas. As a last resort, the ship’s crew switched to cumbersome manual control, but Lemons’ umbilical – the line that delivered gas, light, communications and warm water to combat the ambient 4°C – had snapped. It had snagged on equipment as the ship and diving bell dragged away, so he had effectively become a human anchor for an 8,000-tonne ship. “It rang out like a pistol shot when it broke,” he recalls. The story was retold in the 2019 documentary Last Breath and in a 2025 feature film of the same name starring Woody Harrelson and Peaky Blinders actor Finn Cole as Lemons.

Saturation divers live in pressurised chambers on a dive ship and work around the clock in six-hour shifts. Lowered daily in a diving bell through a hole – the ‘Moon pool’ – in the ship’s hull, they work on oil and gas infrastructure, inspecting and changing pipes, repairing and even welding. It is a claustrophobic, odd existence, but one that Lemons – who grew up in Cambridge and had been encouraged by a family friend – enjoyed. It paid well and was oddly healthy. “You don’t drink alcohol for a month, you breathe pure gas with no pollution, you have to swim around and exercise every day,” he says.

Divers breathe heliox, a mix of oxygen and helium, to avoid the narcotic effects of nitrogen at below 50 metres. Most work in the relatively shallow North Sea takes place at depths of around 100-200 metres, but divers can work down to 350 metres off the coast of Brazil. Decompression in the North Sea requires five days – longer than when returning an astronaut from the Moon, says Gordon – though divers are just a few inches behind a porthole, albeit several inches thick. “So if your mother dies or you have Covid-19, you are still stuck in there,” Lemons says.

Documentary footage shows the strain his umbilical put on the stainless steel fitting in the bell before it snapped. Dive partner Dave Yuasa had turned back to help him, but already Lemons was being dragged away. Close enough to see the whites of each other’s eyes through their helmets, they exchanged a brief glance before Yuasa was pulled away by the drifting ship.

By sheer luck, a couple of steps in utter darkness took Lemons to the base of the manifold he had been working on. Had he turned the other way, rescuers would have taken longer to locate him via his sonar beacon. As he reached the top of the five-metre platform he realised the bell was gone and knew his bail-out gas would not last. Here it gets hazy. The panic subsided – he recalls simply resignation, sadness and then nothing. He doesn’t even remember the cold.

When he came to, he was wheezing in the diving bell after a third diver – played in the film by Harrelson – gave him a couple of rescue breaths. With supreme effort, Yuasa had managed to haul his apparently lifeless body back to the bell. He was blue when they wrested the helmet from his head. Doctors have since struggled to understand how he survived some 30 minutes without gas at the bottom of the North Sea without brain damage. It may have been a combination of the cold and possibly high levels of oxygen stored in his blood under pressure, but they believe he was at the margins of survival.

Safety improvements

While today the industry is highly regulated, the real change has occurred since the pioneering days of saturation diving in the 1970s and 1980s. It was perilous work, with some 79 divers believed to have died in the North Sea since 1967 as the industry broke new ground. “There’s a huge amount of learning and safety being developed over the years,” says Gordon. Equipment is safer, technology more sophisticated. “Although it’s described as a dangerous job, I wouldn’t call it a dangerous environment,” he adds. Nonetheless, around 900 North Sea divers voted for strike action in 2024, citing low pay and dangerous conditions.

For years, it has been predicted that automation will take over the work of this most complex form of diving, with numbers of saturation divers declining and those in post growing older. But there is still demand and a backlog of work, says Gordon, for subsea maintenance and demolition. Legacy oil and gas infrastructure, which has enjoyed a longer shelf life than expected, wasn’t designed for robots.

Saturation divers now go to train mostly in Australia, although the Professional Diving Academy in Dunoon, west of Glasgow, is investing in a purpose-built saturation system to bring back closed bell diver training to the UK from mid-2025. It can cost some £20,000 for experienced divers to train. However, once qualified, they can earn £1,500 a day.

Relatively shallow despite the blustery surface, the North Sea has allowed the industry to perfect subsea technologies. Now the offshore wind sector is benefiting from a supply chain developed over decades. “The future of offshore wind will be floating, and that’s where we have huge amounts of expertise and knowledge in the underwater space,” says Gordon. Here, robotics will play their part, but so too will shallow water divers who can be cheaper and easier to deploy than ROVs, particularly for fiddly jobs or small spaces. “Often the dexterity and ability of a human has still not been matched by an ROV,” says Jerry Starling, director of diving and ROV operations at commercial diving firm RockSalt Subsea.

Unlike in the old days, today’s jobs are meticulously planned and designed, says Starling. “A lot of the hard diving lessons were learned in the North Sea because of the aggressive nature of the weather.” Years ago, drill mud contaminated with hydrocarbons used to be dumped on the seabed. “It used to burn the divers’ skins,” he says. “As history has gone on, we understand the risks for the diver.”

While saturation divers’ suits are largely the same – with piped hot water and a sealed helmet – the regulators and valves are improved, emergency gas lasts longer, umbilicals are now lit and ROVs equipped with navigation and location technology accompany divers, giving supervisors a wide view of work under way.

Underwater welding – deployed to repair oil and gas installations and join pipelines – has earned a reputation for being one of the most hazardous diving jobs and is now heavily regulated. It can be completed wet or dry, says Gordon, who previously helped develop techniques such as ‘hot tap’ pipeline connections at the National Hyperbaric Centre in Aberdeen.

Dry welding requires a chamber through which gas is pumped to remove toxic welding fuels and avoid an influx of inflammable hydrocarbons and dangerous gases. Wet underwater welding can use temperatures of more than 5,500ºC, says Starling. “A number of divers have been killed by burning where they’re cutting steel underwater ... with byproducts of oxygen and hydrogen, which can create a small bomb when mixed.”

In the early days, planning was poor – and crushed fingers, injuries and near misses were more common. “It’s riskier if you have a person down there,” says Starling. “But today there are tools to make everything safer. Incidents are quite few.”

Deadly risks

But around the world, accidents still remind the industry of the dangers. Four commercial scuba divers were killed off the coast of Trinidad in 2022 when they were sucked into an oil pipeline they were working on and trapped in air pockets.

Lemons, who lives in southern France, no longer dives – although he returned to the job just three weeks after the accident and continued for several years. He works as a dive supervisor, mostly in the North Sea and east Asia, and says retelling his story is still cathartic.

“It’s strange what you normalise,” he says. “I didn’t feel traumatised at all, and I’ve never felt frightened by it. I think we felt the euphoria of getting through it. Saturation diving feels very regulated – we don’t hurt people and we don’t let people die.”

He also welcomes increasing automation. “The safest way to avoid hurting a diver is not to put them in the water.”

Chris Lemons says he does not feel traumatised by the 2012 incident

You may also be interested in...

Partners in the LOWNOISER project aim to ‘address the critical environmental challenge of underwater noise pollution from shipping’.

Open-access content

Fabrics designed to keep city dwellers’ body temperatures down could ease the impact of climate change in urban heat islands

Open-access content

The ‘bold visions of future urban living’ are being given a reboot, with AI at the forefront.

Open-access content

Clearly neither Los Angeles burning out west, nor the unusually cold weather in the east that drove the inauguration ceremonies indoors, could persuade incoming President Trump that pulling out of the Paris Agreement was anything but a good idea.

Open-access content

A London school is using AI to teach a class – but will this really help pupils to learn and engage, and lighten the workload of struggling human teachers?

Open-access content

What makes a city so smart – and what are the barriers to enhancing everyone’s lives through this tech?

Open-access content

Amid AI advancements and developments in China, Intellectual Property Office CEO Adam Williams explains why today’s need to protect technology innovations is more pressing than ever.

Open-access content

More from Fossil Fuels

Donald Trump has ordered the US military to purchase energy from coal-fired power plants in a bid to shore up the flagging domestic industry.

Open-access content

The annual cost of decommissioning old oil wells in the North Sea is expected to soar past the sector’s investment in building n

Open-access content

The Maritime and Port Authority of Singapore (MPA) will issue licences from 1 January 2026 for companies to supply methanol as a marine fuel.

Open-access content

More from Health And Safety

A United Airlines flight has faced a mid-air collision with a falling object that is speculated to be a piece of space junk.

Open-access content

Amazon’s fledgling drone delivery service in Arizona is set to resume after being briefly suspended following a collision with a crane.

Open-access content

As we celebrate the 200th anniversary of the first rail passenger journey, one of the UK’s younger government agencies

Open-access content

More from Marine Transport

As the year draws to a close, we at E+T magazine have been looking back at some of the most important trends in engineering and

Open-access content

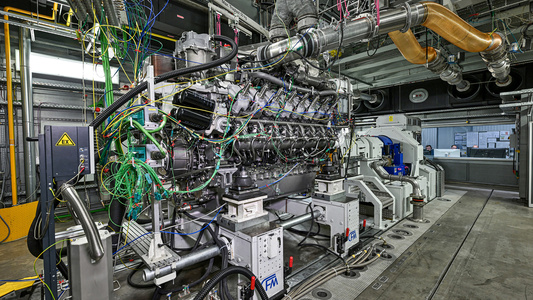

The first high-speed marine engine that runs entirely on methanol has been demonstrated in initial bench tests at Rolls-Royce.

Open-access content

Four rotor sails have been installed on a 325,000-deadweight ton cargo ship by UK firm Anemoi Marine Technologies as part of a technology demonstration designed to cut carbon emissions on long-range shipping.

Open-access content

More from Helena Pozniak

As a historic new treaty to conserve sea life comes into force, how will the world’s most remote oceans be policed and protected?

Open-access content

The IET aims to ‘engineer a better world’, inspiring, informing and influencing the global engineering and technology community. But what does it mean in practice? We asked five experts what engineering a better world means in their sector

Open-access content

Is AI really stealing jobs, as much of the mainstream media would have it? E+T speaks to six engineers who have embraced the tec

Members'-only content

More from Volume 20, Issue 2 - March/April 2025

As fears over its safety have subsided over time, coupled with the need for cleaner energy, nuclear energy has taken on a pivotal role in providing base power generation in the UK. But how are we getting on in building capacity?

Open-access content

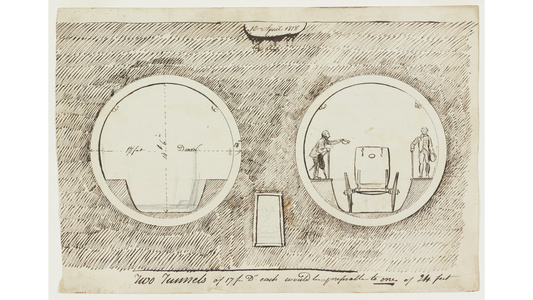

Tanya Weaver looks back at a father and son’s engineering marvel, 20th-century speed limits and the video that launched a platform.

Open-access content

How psychedelic substances helped Kary Mullis with the greatest discovery in modern genetic engineering – PCR

Open-access content