Meta’s Llama 4 model is banned for use by any EU-based entity, with the restriction hardcoded into its license. This unprecedented move isn’t technical—it’s legal—and reflects Meta’s attempt to sidestep immediate regulatory burdens imposed by the EU AI Act.

While framed as “open,” Llama 4’s license blocks entire regions, enforces brand control, and limits redistribution—violating core principles of open source. The result: EU researchers, startups, and institutions are legally locked out, deepening global inequities in AI access.

This is more than a licensing clause—it’s a geopolitical fault line in the future of AI. As Meta redefines what "open" means, truly open alternatives like DeepSeek and Mistral emerge as critical counterweights.

The open-source community now faces a choice: accept corporate-controlled “open(ish)” models—or reclaim openness as a global, equitable standard.

Llama 4 is Meta’s most powerful open-weight AI release to date. With massive context windows, native multimodality, and state-of-the-art reasoning, it rivals closed frontier models like GPT-4, Gemini 2.5, and Claude 3 Opus—yet it’s fully downloadable, customizable, and free to run.

Unless you’re in the European Union.

If your organization is legally domiciled in any EU member state, you are explicitly banned from using Llama 4. Not delayed. Not restricted. Banned. The prohibition is hardcoded into the license—no carve-outs for research, no exceptions for personal use, no workarounds through cloud infrastructure. This is not a bug. It’s the design.

It’s a stark move with massive implications: Meta, one of the world’s largest AI players, has drawn a legal border around Europe and declared its most capable models off-limits.

This isn’t just about a model. This is about who gets to build with tomorrow’s tools—and who doesn’t.

The fallout is immediate. European researchers are locked out. EU startups lose access to the most performant open-weight model on the market. Public institutions face legal risk for doing what used to be standard: studying, improving, and deploying cutting-edge AI.

But the implications go even deeper: if "open" models are now region-gated, what does openness mean anymore? If licensing terms—not compute or capability—dictate who can participate in building the future of AI, then we’re no longer dealing with an open ecosystem. We’re dealing with a fragmented, geopolitical infrastructure of privilege.

The Llama 4 EU ban is more than a legal clause. It’s a fault line in the future of AI access, and it’s happening right now.

To full unpack all the great new features in Llama 4 see Unpacking the New Llama 4 Release

The Llama 4 Community License Agreement includes a direct ban:

“You may not use the Llama Materials if you are... domiciled in a country that is part of the European Union.”

Additional key restrictions:

❌ Use forbidden by any entity domiciled in the EU

❌ Use by organizations with over 700 million monthly active users requires permission

❌ All derivative models must retain “Llama” branding

❌ Attribution is mandatory: “Built with Llama”

❌ Not OSI-compliant — this is not open source

❌ No exceptions for academic, personal, or non-commercial use

This is a region-gated license, not a minor terms tweak.

Though Meta hasn’t officially explained the EU exclusion, the reason is clear:

The EU AI Act introduces strict compliance rules for general-purpose AI, including transparency, documentation, risk mitigation, and potentially even training data disclosures—right at release. These provisions place substantial legal and operational pressure on providers of large models like LLaMA 4.

Meta likely chose to preemptively sidestep regulatory risk by simply cutting off the region. By geofencing the EU, they avoid immediate liability, compliance burdens, and disclosure obligations. It’s not elegant or sustainable, but likely the most straightforward short-term play to get LLaMA 4 out the door without triggering EU scrutiny.

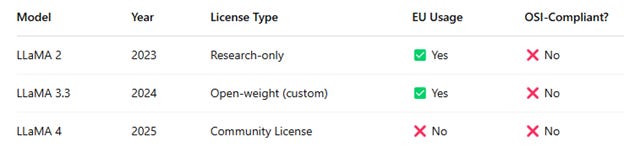

Notably, this clause did not exist in LLaMA 2 or 3. It is new in LLaMA 4 and reflects a clear legal shift in how Meta manages exposure—not necessarily a long-term strategy, but a deliberate move to buy time and defer the complexity.

On the surface, this decision may appear shortsighted. But it likely reflects a calculated hedge. The cost and complexity of complying with evolving AI regulations—especially in their earliest and most ambiguous stages—can be enormous. Rather than risk early enforcement or set a precedent for disclosures, Meta seems to have chosen to delay engagement until the regulatory environment stabilizes or until they can resource compliance more fully.

Still, the approach carries significant long-term risk. Scaling globally without addressing these obligations is untenable. As more jurisdictions move toward similar transparency and risk standards, the strategy of carving out geographies becomes less viable. Meta will eventually need to build infrastructure—legal, technical, and organizational—to meet these expectations.

Unless they’re banking on a reversal or watering down of regulatory momentum (which seems highly unlikely), this is just a temporary maneuver. The pressure to comply won’t disappear—it will only grow.

Almost certainly—through license enforcement, not technical blocks.

There are no IP blocks or download limits on the weights, but:

Meta can send takedown requests to EU-based developers, researchers, and companies

Cloud hosts (e.g., Hugging Face, AWS, Azure) may begin geofencing or flagging Llama 4 use for EU users

Deploying or fine-tuning the models in the EU creates real legal exposure

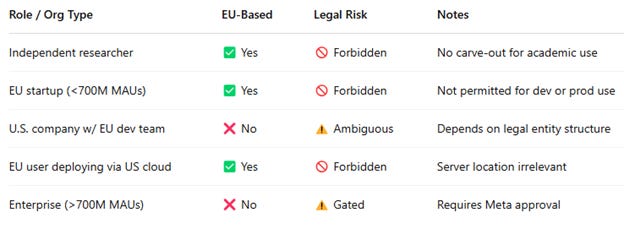

⚖️ License Risk Matrix

The impact is immediate and severe:

🧪 Researchers in the EU can’t legally fine-tune, train, or evaluate Llama 4

🚫 Startups cannot integrate or build commercial apps on top of it

🧩 Enterprises face risk even for internal experiments

Meanwhile, teams in the US, China, and elsewhere have full access. This creates a structural innovation gap—Europe is legally cut off from a state-of-the-art model.

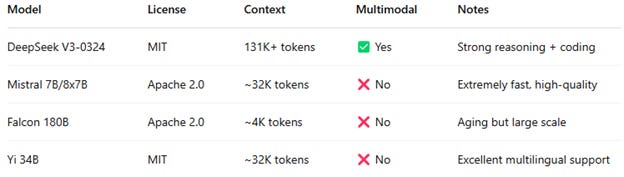

Meta’s move creates a strategic opening for DeepSeek:

✅ MIT license — fully OSI-compliant

✅ No regional restrictions

✅ 37B active parameters, multimodal MoE architecture

✅ Comparable benchmark performance to Maverick (Llama 4’s top-tier model)

DeepSeek V3-0324 is now the most powerful model legally available to EU developers.

This strengthens DeepSeek’s position as:

The default model for open European innovation

A true philosophical counterweight to region-gated “open” models

A candidate for institutional and public-sector adoption across Europe

Here are viable, legally clear options for EU teams:

DeepSeek leads in performance and licensing freedom. Mistral remains unmatched for speed.

✅ If You Define “Ethical” as Risk-Averse

Meta is minimizing exposure to a highly regulated environment. By avoiding the EU, it avoids violating laws or deploying unsafe systems into legal ambiguity.

One flavor of ethics: do no harm, even if it means restricting access.

❌ If You Define “Ethical” as Equitable, Transparent, Open

This move:

Gates access by geography

Prevents academic and public contributions

Centralizes AI control under corporate licensing terms

Another flavor of ethics: democratize power and access—don’t ration it.

So is it ethical? From Meta’s POV, yes. From the perspective of fairness and global collaboration? No.

Q: Can I use Llama 4 in the EU if I run it on AWS in the US?

A: No. The restriction is based on your company’s legal domicile, not your cloud provider.

Q: What if I’m just using it for academic or nonprofit research?

A: Still forbidden. The license makes no exceptions for use case or intent.

Q: Will Meta actually enforce this?

A: Possibly not aggressively at first, but enforcement is likely to escalate via legal channels and partner pressure.

The pattern is clear: more capability, more control.

📆 LlamaCon (April 29) — Meta may address Behemoth access and licensing questions

🧠 Behemoth release — Will the teacher model inherit the same restrictions?

⚖️ EU AI Act enforcement — Will other AI companies follow Meta’s lead?

🛠 Cloud provider moves — Will AWS, Hugging Face, and others start geofencing?

Meta calls Llama 4 “open,” but the open-source community needs to ask: open for whom, under what terms, and at what cost?

Llama 4 is not open source by any OSI-approved definition. Its license restricts:

🌍 Where it can be used — EU entities are banned

🏢 Who can use it — Orgs with over 700M MAUs need permission

📦 How it can be distributed — Must retain “Llama” branding

⚙️ What you can do with it — Attribution and naming control required

There’s no field-of-use neutrality, no redistribution freedom, and no regional equity. These restrictions break the foundational principles of open source—yet Meta continues to market Llama as “open.”

Calling Llama 4 open source is like calling Netflix open source because the play button works. You can interact with it—but only on their terms, with no control over what’s behind the screen.

See The LLaMA 4 Deception: How Meta Hijacked the Open Source Label — and Why It Matters

🚨 This Creates Several Problems

1. Dilution of the Term “Open Source”

When a model this prominent is branded as “open” but excludes entire continents, the term starts to lose meaning.

Open source was built on clear definitions: free to use, modify, and share without discrimination. Llama 4’s license violates those norms but leverages the language of openness for PR and developer goodwill.

2. Split Ecosystem

We’re now facing a two-track future:

✅ Truly open models (like DeepSeek, Mistral, Falcon)

❌ Corporate-controlled “open” models with heavy restrictions

This creates friction and fragmentation. Researchers and developers trying to collaborate across borders now run into licensing headaches, use-case limits, and brand entanglements.

3. Pressure on Legitimately Open Alternatives

Projects like DeepSeek, Mistral, and Eleuther are actually open—but without Big Tech branding, they face:

⚖️ Resource constraints

📉 Media underrepresentation

🧱 Distribution challenges

If Big Tech dominates the “open” narrative with closed-but-marketed models, true open-source projects lose ground, despite offering more freedom and community alignment.

4. Loss of Ownership and Forking Rights

Open source isn’t just about access—it’s about freedom:

To fork

To audit

To improve

To republish independently

Llama 4’s license prevents true forks. Any improvement you make still carries Meta’s name and branding. That’s not community-driven software—it’s a vendor product wrapped in the aesthetics of openness.

🧠 So, Is Llama 4 Open Source?

No. It’s open-weight, meaning you can download and run it—but it is not open source in spirit or in law.

And Meta isn’t alone. Many labs are now releasing “open(ish)” models with:

Trademark restrictions

Geographic limits

Use-case constraints

Forced attribution

But Llama 4 goes further. It’s the first major model to outright ban an entire region. That’s not just precedent—it’s a turning point.

⚠️ Why This Matters

Open source has been the backbone of modern innovation—from Linux to PyTorch, Hugging Face to Python. When major players co-opt the language of openness while maintaining centralized control, they distort the future of AI development.

If we don’t draw a clear line between what’s truly open and what’s merely accessible under corporate conditions, we risk turning “open source” into a marketing term with no substance.

This isn’t just about Meta. It’s about the future of open AI access. If regional, corporate, or usage restrictions become standard, we lose the foundation of an open AI commons.

We need:

Transparent licensing practices

Clear definitions of “open” that align with community values

Open models that respect global participation

If you’re building in the EU—or anywhere—you have a stake in this.

Llama 4 is powerful. It’s free. It’s open-weight. But if you’re in the EU, you’re legally barred from using it.

This is not a feature gap. It’s a deliberate licensing firewall—a signal that the open AI ecosystem is becoming fractured, gated, and governed by legal risk, not community values.

By banning EU entities, enforcing brand lock-in, and blocking redistribution, Meta has introduced a new category of “open”: available, but not equitable; accessible, but not free.

It’s a watershed moment for open-source AI.

The fallout is immediate:

EU researchers and developers are locked out

Startups and enterprises face real legal risk

The definition of “open” is eroding in plain sight

Meanwhile, truly open alternatives—like DeepSeek V3-0324, Mistral, and Yi—offer free use without borders, licenses, or strings. But they lack the branding muscle and market dominance to compete on reach alone.

Meta didn’t just release a model. It drew a border around who gets to build the future—and who doesn’t.

And so the open-source community now stands at a crossroads:

Accept the corporatization of “openness”

Or reclaim it—loudly, clearly, and collectively

Because open-weight is not open source. And access on paper is not access in practice.

If openness ends at the border, it was never really open to begin with.

The future of open AI won’t be decided by companies alone—it’ll be shaped by the communities that choose to push back.

This is your line in the sand. Don’t look away.

#Llama4 #OpenAI #AIGovernance #OpenSourceAI #EUAIAct #DeepSeek #MistralAI #LLM #MetaAI #AIethics #AIstrategy #OpenWeight #LlamaLicense #GlobalAI