🚨 Vulnerability Status: Formally Tracked

As of , this vulnerability is being formally tracked by multiple security coordination bodies:

- CERT/CC (VINCE): Report VU#840183 (Status: Open)

- NotCVE ID: NotCVE-2026-0001[1]

- Severity: CVSS 8.7 (High)

- Attack Vector: Network-based (BGP hijacking, network interception)

- Impact: Critical (Domain Integrity, TLS MITM capability)

- Severity: CVSS 8.7 (High)

Technical Classification

The vulnerability has been formally classified under the following enumeration standards:

- CWE-1188 : Insecure Default Initialization of Resource (Core issue: Cloudflare defaults to insecure CAA injection).

- CWE-693 : Protection Mechanism Failure (Failure of the

accounturirestriction). - CAPEC-94 : Adversary in the Middle (AiTM) (The resulting attack vector).

- CAPEC-584 : BGP Route Disabling / Manipulation (Prerequisite for the attack).

- CAPEC-598 : DNS Spoofing (Alternative network manipulation vector).

Audio Overview

Audio overview of how Cloudflare's Universal SSL weakens RFC 8657 protections.

Video Overview

Video walkthrough of the Cloudflare CAA validation gap and resulting MitM exposure.

TL;DR

The Mechanism

Cloudflare’s Universal SSL injects permissive CAA records that override user DNS constraints, causing certificate authorities to ignore strict account-binding checks.

The Risk

This enables BGP hijacking and network interception to obtain unauthorized TLS certificates by bypassing accounturi and validationmethods.

The Precedent

The configuration replicates the gap exploited in the 2023 jabber.ru MitM attack, where intercepted traffic satisfied http-01 validation challenges.

The Mitigation

Cloudflare must stop overriding user DNS records or fully implement RFC 8657 to restrict certificate issuance to the domain owner’s authorized ACME account.

On , Cloudflare disclosed and patched a separate ACME-related vulnerability in their WAF bypass logic, as reported by security researchers FearsOff. [2]

Critical Distinction: This is NOT a fix for NotCVE-2026-0001. Cloudflare patched an implementation bug (WAF bypass via ACME challenge logic) but continues to retain the architectural flaw (CAA override) identified in this article. The swift Cloudflare response to the FearsOff WAF vulnerability—between reporting and patching—while remaining silent on the RFC 8657 design flaw for over a year, suggests the silence is deliberate rather than technical.

The Venezuela BGP Leak Confirmation

In , a massive BGP leak involving Venezuela’s state-owned ISP (CANTV,AS8048) made global headlines. In their analysis of the incident, Cloudflare explicitly stated that “BGP route leaks happen all of the time, and they have always been part of the Internet.”

[3a]

This admission highlights exactly why the security gap described in this article is so critical. If BGP leaks are “common” (whether accidental or malicious), then the network layer cannot be trusted for domain validation.

Yet, as detailed below, Cloudflare’s Universal SSL default configuration actively disables the specific IETF standard (RFC 8657) designed to prevent these common BGP leaks from being weaponized to issue fraudulent certificates.

I have opened a new discussion on this specific contradiction with the Cloudflare team [4a].

Introduction: A Critical Security Gap in Cloudflare’s Universal SSL

I have identified a significant, yet easily fixable security weakness in Cloudflare’s Universal SSL that affects millions of users, and my attempts to address it directly with Cloudflare [5a] have been… well, let’s call it “unsuccessful.”

The issue is best understood through the lens of the jabber.ru MitM attack [6] that took place in . At that time, government-backed attackers were able to intercept traffic for jabber.ru at the network level. By doing this, they could satisfy the http-01 domain validation challenge from Let’s Encrypt and were issued a valid TLS certificate for the domain. They did not need to compromise the server itself.

RFC 8659 vs RFC 8657: The CAA Standards Explained

To understand the problem, you need to understand the solution. The defense against this attack is built on two IETF standards.

1. The Basic Standard: RFC 8659 (CAA)

First, there’s the basic CAA standard, [7], which updates the original [8]. This is what you can call “brand-level trust.” It lets you put a record in your DNS that says:

david-osipov.vision. IN CAA 0 issue “letsencrypt.org”This record tells all Certificate Authorities (CAs): “Only Let’s Encrypt can issue a certificate for my domain.”

This is good, but it’s not enough. It means anyone who can pass Let’s Encrypt’s validation challenge can get a cert. If an attacker hijacks your web server or (as in the jabber.ru case) your network traffic, they can pass the challenge and get a valid cert from your authorized CA.

2. The Real Standard: RFC 8657 (The ACME Extensions)

This is where [9] comes in. It was published in and was designed specifically to prevent this kind of attack. It’s an upgrade from “brand-level trust” to a “process-level trust.” It adds two critical parameters: accounturi and validationmethods.

The accounturi parameter is your “second factor.”

It’s a record that says: “Only Let’s Encrypt, using my specific account, can issue a certificate for my domain.”

accounturi)david-osipov.vision. IN CAA 0 issue “letsencrypt.org; accounturi=https://acme-v02.api.letsencrypt.org/acme/acct/MY_ACCOUNT_ID”If this had been in place for jabber.ru, the attackers’ request from their own Let’s Encrypt account would have been rejected by the CA, and the attack would have failed. The author of RFC 8657 (Hugo Landau) himself confirmed this in his paper Mitigating the Hetzner/Linode XMPP.ru MitM interception incident[10].

The validationmethods parameter is your “attack vector shield.”

This parameter lets you specify how the CA is allowed to validate your domain. This is the part that would have directly blocked the jabber.ru attack.

Technical Deep Dive: http-01 vs. dns-01

http-01challenge: The CA asks you to put a specific file on your web server athttp://your.domain/.well-known/acme-challenge/. This proves you control the web server, but it’s vulnerable to network-level BGP hijacking. Attackers don’t need to touch your server; they just need to intercept the CA’s request, which is exactly what happened tojabber.ru.dns-01challenge: The CA asks you to put a specific TXT record in your DNS. This proves you control the DNS, which is almost always a more secure and separate asset from your web server.

By setting this record, you forbid the CA from using the vulnerable http-01 method entirely:

dns-01david-osipov.vision. IN CAA 0 issue “letsencrypt.org; validationmethods=dns-01”- accounturi

- A CAA parameter that binds issuance to a particular ACME account URI (prevents issuance from other ACME accounts).

- validationmethods

- A CAA parameter that restricts which ACME validation methods a CA may use (e.g.,

dns-01only). - http-01

- The ACME HTTP-based challenge; proves control of a web server but is vulnerable to network-level interception (BGP hijack).

- dns-01

- The ACME DNS-based challenge; proves control of DNS records and is generally more robust against network interception.

If jabber.ru had either of these RFC 8657 records, the attack would have been dead on arrival.

The Cloudflare Problem: A “Feature Collision”

Now, the core issue. As a B2B Product Manager, I don’t see this as a “bug”—I see it as a feature collision where the needs of a (badly designed) product feature are actively destroying user security.

Here is the problem: When you use Cloudflare’s free Universal SSL, Cloudflare automatically adds its own CAA records for its partner CAs (Let’s Encrypt, Google Trust Services, etc.) [11a]. These records do not use the accounturi or validationmethods parameters.

Worse, if you try to add your own secure CAA record (like the ones above, that I showed you), Cloudflare’s system sees it and says, “Oh, the user is adding a CAA record! I should ‘helpfully’ add my own permissive ones too! And if user’s records conflict with mine, I’ll just replace them with mine to make sure my system works smoothly.”

So the final DNS response looks like this:

... IN CAA 0 issue "letsencrypt.org; accounturi=.../MY_ACCOUNT_ID"(Your secure record is being replaced by…)... IN CAA 0 issue "letsencrypt.org"(…this one. Cloudflare’s “helpful” insecure record)

According to the rules, a CA is allowed to issue a certificate if any matching record permits it. Your secure record (1) correctly blocks the attacker, but Cloudflare’s injected record (2) replaces your own and it explicitly permits a malicious actor to carry out an attack.

Cloudflare’s “feature” actively and silently nullifies the IETF-standard security control. It recreates the exact vulnerability that jabber.ru suffered from for millions of its users.

Now look at practical exploit:

- Setup: A user delegates their

dns-01challenge using a CNAME to anacme-dnsserver they don’t fully control (a common, secure pattern). - Intended Security: The user sets an

accounturirecord to ensure only their own ACME account can use this delegation. - The Cloudflare Flaw: Cloudflare replaces user’s records with its permissive

issue “letsencrypt.org”record. - The Attack: The (untrusted) admin of the

acme-dnsserver can now use their own Let’s Encrypt account to get a valid certificate for the user’s domain, completely bypassing the user’saccounturi“second factor.”

This Isn’t Just Cloudflare: A Pattern of “Platform vs. Provider”

To be fair (and to be more “academic”), Cloudflare isn’t the only one with this problem. This is a systemic flaw in any “integrated platform” that bundles “magic” automated SSL with hosting. The magic must override your security to function.

This shows a clear, industry-wide divide. “DNS-Only” providers sell you security and control. “Integrated Platforms” sell you convenience, often at the expense of security.

Theoretical Context: Why This Is a “Feature Collision” and an Engineering Dilemma

Theoretically, the “correct” solution would be for Cloudflare to simply not interfere: if a user defines a CAA record, the system should not override it. However, architecturally, this creates a dilemma for “integrated platforms”:

- If the user does NOT add a CAA record: Cloudflare MUST add its own to indicate which CA will issue Universal SSL certificates.

- If the user DOES add a CAA record: The lightweight solution (which Cloudflare uses) is to add its own record in addition to the user’s. The strict solution is to respect the user’s choice and allow them full CAA control.

Cloudflare chose the lightweight approach. It’s more convenient for their engineers, but more dangerous for users.

The Industry’s Answer: Multi-Perspective Issuance Corroboration (MPIC)

While many platforms continued to ignore or override RFC 8657, the CA/Browser Forum moved to address the root cause at the validation layer. In , the Forum approved Ballot SC-067 v3, which requires Certificate Authorities to use Multi-Perspective Issuance Corroboration (MPIC) instead of relying on a single, local vantage point for domain validation.

The Princeton connection

The CA/Browser Forum specifically cites the 2018 Princeton paper Bamboozling Certificate Authorities with BGP [19a] as a primary motivation — the attack model described there is the exact threat MPIC is designed to mitigate.[20]

The vote record shows unusually broad agreement: major issuers and major platform consumers supported the change.

Implementation timeline

According to the updated TLS Baseline Requirements and the ballot text, the rollout was staged:

- : MPIC becomes RECOMMENDED for all CAs.

- : MPIC becomes MANDATORY (minimum 2 independent perspectives required).

- : Requirement tightens to a minimum of 3 independent perspectives.

Why MPIC doesn’t replace RFC 8657

MPIC and RFC 8657 are complementary controls:

In short: MPIC significantly reduces the risk of BGP-based attacks, but it is not a silver bullet. A 2023 Princeton study [21]—co-authored by Henry Birge-Lee—found that standard MPIC deployments offer only about 88.6% median resilience against determined BGP adversaries, largely due to the expanded attack surface of DNS infrastructure.

This leaves a quantifiable security gap (~11%) that network-layer defenses cannot close on their own. This makes identity-layer defenses like RFC 8657 (Account Binding) mandatory, not optional, for high-value domains.

Cloudflare’s refusal to honour accounturi and validationmethods therefore remains a meaningful gap in defense-in-depth, even though MPIC should eliminate the easiest network-only attacks by 2025.

The “Persistent” Shift: Leaving Cloudflare Behind

While Cloudflare continues to block RFC 8657 support, the rest of the industry has effectively declared it a requirement for the next generation of web security.

In November 2025, the IETF ACME Working Group officially adopted draft-ietf-acme-dns-persist-00 [22a]. This new draft standard allows for “Persistent DNS” validation—a critical feature for IoT devices and multi-tenant platforms that cannot perform 90-day DNS challenges.

Critically, this new standard mandates RFC 8657. It requires the use of the accounturi parameter to bind the persistent DNS record to a specific account. Without this binding, a persistent record would become a “bearer token” that any attacker could reuse.

The authorship of this draft highlights the industry divide. It was co-authored by engineers from Fastly and Amazon Trust Services—direct competitors to Cloudflare—along with researchers from Crosslayer Labs. While Cloudflare’s competitors are actively standardizing the usage of accounturi to secure their platforms, Cloudflare’s Universal SSL product remains architecturally incompatible with it.

The RFC 8657 Support Matrix (2026)

The following table illustrates the growing divide between security-forward providers and those prioritizing legacy convenience models.

The Synergy with DNSSEC

The refusal to support RFC 8657 is doubly dangerous when we consider the role of DNSSEC. As noted by researcher Henry Birge-Lee in discussions with the CA/Browser Forum, the combination of CAA + DNSSEC + RFC 8657 is the only mechanism that allows certificate issuance to be “completely based on cryptographic trust.” [29a]

“Our cryptographic DV design provides domain owners the critical capability of declaratively securing their domain names against network attacks on certificate issuance.”

— Birge-Lee et al., “Cryptographically-Secured Domain Validation” (2024) [30]

Without accounturi, even a DNSSEC-signed domain is vulnerable if the attacker can intercept the validation traffic (as seen in the Venezuela incident). By supporting RFC 8657, a domain owner can cryptographically lock issuance to a specific account key. Cloudflare’s overriding of these records effectively downgrades a domain’s security posture, regardless of whether they use DNSSEC or not.

But… Is This Really a Problem? (Yes, It Is)

The jabber.ru incident is the primary, powerful case study, but the Web PKI is a graveyard of similar incidents that these standards were built to prevent.

- - DigiNotar Breach: A complete CA compromise led to fraudulent certificates for Google, Yahoo, and more, used for state-level MitM attacks. [31] [32a]

accounturi(or even basic CAA) would have been a defense. - - - WoSign & StartCom: These CAs were distrusted for numerous failures, including issuing certs without proper validation. [33] [32b]

validationmethodswould have prevented issuance via non-standard, weaker methods. - - Chaining Web Vulnerabilities: A researcher showed how a simple path traversal vulnerability on a web server could be used to satisfy an

http-01challenge. [34] Avalidationmethods=dns-01policy would have rendered this entire attack class useless. - - Princeton BGP Hijacking Study: A foundational paper from Princeton University, [19b], demonstrated how BGP hijacking could be weaponized to defeat

http-01validation. Thejabber.ruattack was a real-world execution of this exact threat model (network-level interception). - January 2026 - Venezuela Routing Leaks: A massive route leak involving CANTV (AS8048) demonstrated that BGP misconfiguration remains a daily reality. While Cloudflare attributes this to misconfiguration, it proves that traffic interception is common. As Henry Birge-Lee argued in the Server Certificate Working Group, reliance on network perspective alone (even MPIC) is insufficient without the cryptographic guarantees of DNSSEC and account binding. [3b] [29b]

In each case, accounturi or validationmethods would have provided a critical, preventative layer of defense.

My Attempt to Engage Cloudflare

I’m not the first to notice this. I posted a detailed breakdown of this issue on the Cloudflare Community forum on .

Here is a verbatim summary in five acts from that thread [5b]:

Act 1 (): I submit the request “Critical Security Gap: Cloudflare Must Fully Support RFC 8657 CAA”.

Act 2 (): A Cloudflare Team member (

mmalden) finally responds. They claim the feature isn’t supported because RFC 8657 isn’t fully passed (incorrect) and suggest Certificate Transparency logs as an alternative. This response is marked as the “Solution.”Act 3 (): I post a detailed rebuttal, citing Cloudflare’s history of adopting draft protocols (TLS 1.3, QUIC) years before finalization, and pointing out that RFC 8657 is already a proposed standard. I conclude: “The only logical conclusion… is that withholding RFC 8657 support is a business decision.”

Act 4 ():

grey: “I really love talking with myself in this thread :grinning_face:”(My rebuttal remains unanswered. The “Solution” tag remains on the incorrect answer.)Act 5 ():

This topic was automatically closed 2 days after the last reply. New replies are no longer allowed.

A critical, user-reported security gap, with 1.3k views and 20 likes, was not properly “resolved.” It was auto-closed by a robot.

To bring more attention to this, I also published an article on the popular Russian tech site Habr.com [35] on , which became the top post of the week. This shows the community understands the issue, even if Cloudflare’s support process is designed to ignore it.

Update (January 15, 2026): Following Cloudflare’s public admission that BGP route leaks happen all of the time,

[3c] regarding the Venezuela incident, I have opened a new, specific inquiry on their community forum asking why their SSL product disables the primary defense against those very leaks. You can support that request here: [4b].

The Core Contradiction: A Business Decision, Not a Technical Lag

A Cloudflare team member claimed this is not a vulnerability and that they would comply if RFC 8657 were passed.

This response is, in my view, disingenuous.

- RFC 8657 was published in . It’s been a standard for six years.

- Cloudflare has a

long history

of implementing critical security protocols like TLS 1.3 [36] and QUIC [37] while they were still in draft status.

To claim they must “wait” for this standard is inconsistent with their entire innovative culture. This isn’t technical lag; it’s a business decision.

When mmalden from the Cloudflare Team responded, they stated they would comply “should RFC 8657 be passed.” This response—which was officially marked as the “Solution” to the thread—is demonstrably false and contradicts Cloudflare’s own engineering history.

As I pointed out in my rebuttal to the team:

- The Standard is Already “Passed”: RFC 8657 is already a Proposed Standard on the IETF standards track.

- The “Draft” Status is not an Excuse: Cloudflare has a

long history

of implementing protocols years before they were finalized.

In their blog post on QUIC, Cloudflare explicitly bragged about this culture: “The Cloudflare Systems Engineering Team has a long history of investing time and effort to trial new technologies, often before these technologies are standardised or adopted elsewhere.”

[39b]

Yet, for RFC 8657 standard that closes a critical security hole, they claim they must wait for bureaucracy?

Furthermore, the team suggested reliance on Certificate Transparency (CT) logs as a mitigation. As I explained to them, CT logs are a detection tool, not a prevention tool. They alert you after the attacker has already issued a fraudulent certificate and intercepted your traffic. This is a classic CWE-1188 weakness.

This confirms that the lack of support is not a technical oversight or a standards issue. It might be a conscious business decision to keep the “free” product vulnerable while gating secure CAA records behind paid plans.

What Should Be Done (The Fix is Not Complicated)

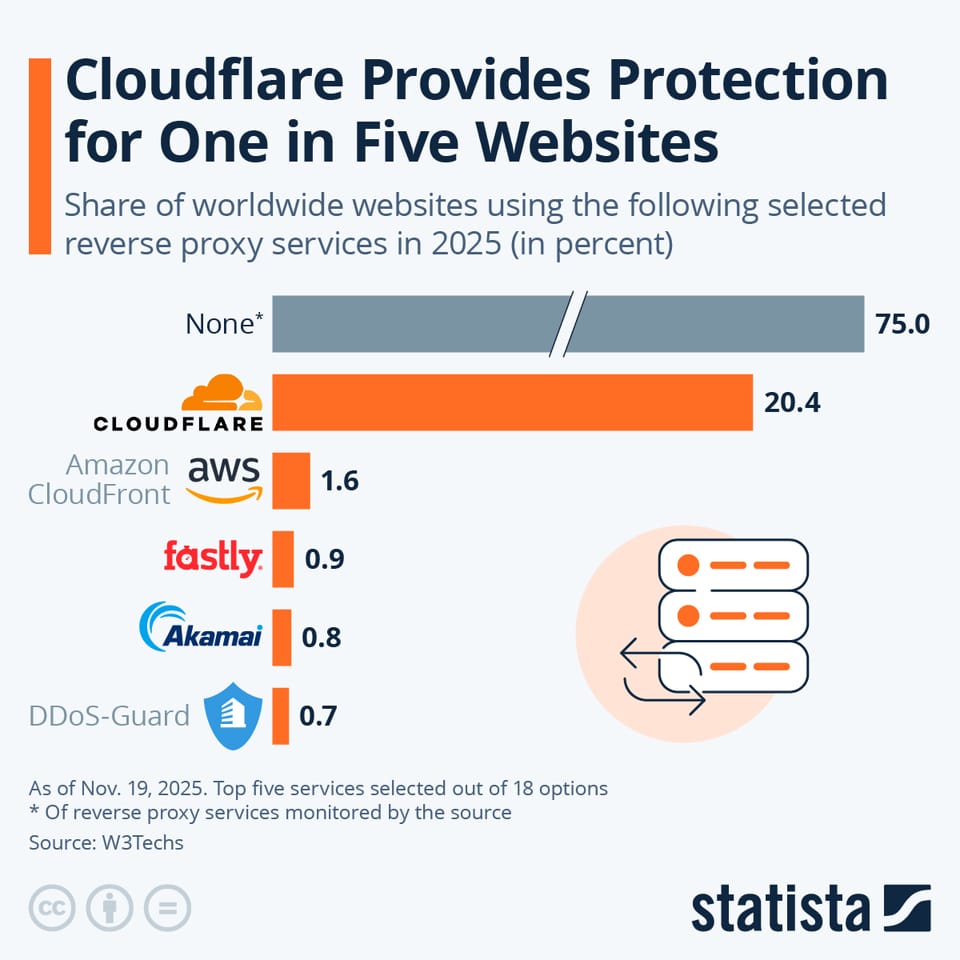

Cloudflare, which powers a massive portion of the web (as of , 21.2% of all websites, representing 82.1% of all websites whose reverse proxy service is known

[42], compared to prior reports of 20.4% of all sites with 81.6% market share [43] [44]), should do the following:

Source: Statista — Infographic. You will find more infographics at Statista.

- Secure Universal SSL by Default: Stop injecting permissive records. Instead, inject restrictive records using

accounturifor Cloudflare’s own internal ACME accounts. This gives users the best of both worlds: they are protected by default, and if they add their ownaccounturirecord, both are valid (theirs and Cloudflare’s), but an attacker’s is not. - Enable Full User Control: Update the DNS logic. If a user defines a record for

letsencrypt.org, do not inject a duplicate, permissive record for the same CA. Trust your user. This is a simpleif (user_record_exists) { do_not_inject } - Be Transparent: Update the documentation [11b] to explicitly explain this override behavior and the risks it creates, instead of hiding it in the fine print.

What can be done now?

Until Cloudflare updates their Universal SSL logic to respect user-defined accounturi and validationmethods parameters, there is no easy configuration for Free or Pro plan users that guarantees protection against this specific MitM vector.

However, if your threat model requires strict CAA enforcement (RFC 8657), you can achieve it by taking full control of certificate issuance:

- Disable Universal SSL: Navigate to SSL/TLS > Edge Certificates in your Cloudflare dashboard and toggle Disable Universal SSL. This is the critical step that stops Cloudflare from automatically injecting the permissive CAA records that override your policies.

- Warning: This will immediately break HTTPS on your site unless you have a Custom Certificate uploaded or an Advanced Certificate active.

- Upload Custom Certificates (Requires Business or Enterprise Plan): For complete control, you must manually issue your own certificates (e.g., using Certbot/Let’s Encrypt with your restricted ACME account) and upload them to Cloudflare.

- Why this works: By managing the issuance yourself, you ensure that only your specific ACME account is used. Cloudflare’s systems effectively become a passive pipe for the certificate you provide, meaning they no longer need to inject permissive CAA records to validate the domain on your behalf.

- Requirements: The ability to upload your own custom certificates is restricted to Business and Enterprise plans.

- Note on Advanced Certificate Manager (ACM): While the paid ACM add-on allows you to order specific certificates on lower-tier plans, Cloudflare still manages the issuance process. Therefore, ACM may not strictly prevent the CAA override behavior described in this article.

- For Everyone Else (Free/Pro): Aggressive CT Monitoring: If you cannot upgrade to a Business plan to upload your own certificates, you must rely on detection rather than prevention. Set up rigorous Certificate Transparency (CT) monitoring (using tools like

certstreamor Cloudflare’s own alerts). If you see a certificate issued for your domain by a CA you use (like Let’s Encrypt) but without your authorization, treat it as an immediate security incident.

I hope that with enough community attention, we can persuade Cloudflare to close this gap for everyone, not just their paying customers.

Thank you for taking the time to read this! I hope it was useful.