» Press Info, Summary, Contact

Report: How thousands of companies monitor, analyze, and influence the lives of billions. Who are the main players in today’s digital tracking? What can they infer from our purchases, phone calls, web searches, and Facebook likes? How do online platforms, tech companies, and data brokers collect, trade, and make use of personal data?

By Wolfie Christl, Cracked Labs, June 2017.

Contributors: Katharina Kopp, Patrick Urs Riechert.

Illustrations: Pascale Osterwalder.

In recent years, a wide range of companies has started to monitor, track and follow people in virtually every aspect of their lives. The behaviors, movements, social relationships, interests, weaknesses and most private moments of billions are now constantly recorded, evaluated and analyzed in real-time. The exploitation of personal information has become a multi-billion industry. Yet only the tip of the iceberg of today’s pervasive digital tracking is visible; much of it occurs in the background and remains opaque to most of us.

This report by Cracked Labs examines the actual practices and inner workings of this personal data industry. Based on years of research and a previous 2016 report, the investigation shines light on the hidden data flows between companies. It maps the structure and scope of today’s digital tracking and profiling ecosystems and explores relevant technologies, platforms and devices, as well as key recent developments.

While the full report is available as PDF download, this web publication presents a ten part overview.

In 2007, Apple introduced the smartphone, Facebook reached 30 million users, and companies in online advertising started targeting ads to Internet users based on data about their individual preferences and interests. Ten years later, a vast landscape of data companies has emerged that consists not only of large players such as Facebook and Google but also of thousands of other businesses from various industries that continuously share and trade digital profiles with each other. Companies have begun combining and linking data from the web and smartphones with the customer data and offline information that they have been amassing for decades.

The pervasive real-time surveillance machine that has been developed for online advertising is rapidly expanding into other fields, from pricing to political communication to credit scoring to risk management. Large online platforms, digital advertising companies, data brokers, and businesses in many sectors can now identify, sort, categorize, assess, rate, and rank consumers across platforms and devices. Every click on a website and every swipe on a smartphone may trigger a wide variety of hidden data sharing mechanisms distributed across several companies and, as a result, directly affect a person’s available choices. Digital tracking and profiling, in combination with personalization, are not only used to monitor, but also to influence peoples’ behavior.

„You have to fight for your privacy or you will lose it“

Eric Schmidt, Google/Alphabet,

2013

I. Analyzing people

Scientific studies show that many aspects

of someone’s personality can be inferred from data on web searches, browsing

histories, video viewing behaviors, social media activities, or purchases. For example, sensitive personal attributes such

as ethnicity, religious and political views, relationship status, sexual

orientation, and alcohol, cigarette, and drug use can be quite accurately inferred from someone's Facebook likes. Analysis of social network profiles can

also predict personality traits such as emotional stability, life satisfaction,

impulsivity, depression and sensationalist

interest.

Analyzing Facebook likes, phone data, and typing patterns

Similarly, personality traits can be

inferred from information about the websites

someone has visited, as well as from phone

call records and data about mobile app usage. Browsing history can reveal information about

someone’s occupation and educational level. Canadian researchers have even

successfully calculated emotional states

such as confidence, nervousness, sadness, and tiredness by analyzing typing

patterns on a computer keyboard.

II. Analyzing people in finance, insurance and healthcare

The results of today’s methods of data mining and analytics rely

on statistical correlations with certain probability levels. Although they may predict

attributes and personality traits significantly above chance, they are naturally

not accurate in every case. Nevertheless, such methods are already used to sort,

categorize, label, assess, rate, and rank people not only for marketing

purposes, but also for making decisions in highly consequential areas such as finance,

insurance, and healthcare, among others.

Credit assessment based on digital behavioral data

Startups such as Lenddo, Kreditech,

Cignifi and ZestFinance already utilize data from

social media, web searches, or mobile phones to calculate someone’s creditworthiness

without actually using data related to financial transactions. Some also draw

on information on how someone fills out an online form or navigates

on a website, the grammar

and punctuation of one’s text messages, and the battery

status on said individual’s phone. Some companies even include data about

someone’s friends

on a social network in calculating credit scores.

Cignifi, which calculates credit scores

from the timing and frequency of phone calls, sees itself as the “ultimate data monetization platform for mobile

network operators". Large companies, including MasterCard, the mobile

network provider Telefonica, the credit

reporting agencies Experian

and Equifax, as well as the Chinese search giant

Baidu,

have started to partner with such startups. The larger-scale application of

such services is particularly on the rise in the countries of the global south,

as well as for vulnerable population groups in other regions.

Conversely, credit data also flows into online

marketing. On Twitter, for example, marketers can target ads by the

predicted creditworthiness of Twitter users based on data from the consumer data broker Oracle. Going a step

further, Facebook has registered a patent

for credit assessment based on the credit ratings of someone’s friends on a

social network. Nobody knows whether it plans to turn this total integration of

social networking, marketing, and risk assessment into reality.

„We feel like all data is credit data, we just don’t know how to use it yet“

Douglas Merrill, founder of ZestFinance and former chief information officer at Google,

2012

Predicting health based on consumer data

Data companies and insurers are working on

programs that use information on consumers’ everyday lives to predict their

health risks. For example, the large insurer Aviva, in cooperation with

the consulting firm Deloitte, has predicted individual

health risks, such as for diabetes, cancer, high blood pressure and

depression, for 60,000 insurance applicants based on consumer

data traditionally used for marketing that it had purchased from a data

broker.

The consulting firm McKinsey has helped

predict the hospital costs of patients based on consumer data for a “large

US payor” in healthcare. Using information about demographics, family

structure, purchases, car ownership, and other data, McKinsey stated that such “insights

can help identify key patient subgroups before high-cost episodes occur”.

The health analytics company GNS Healthcare

also calculates individual

health risks for patients from a wide range of data such as genomics,

medical records, lab data, mobile health devices, and consumer

behavior. The company partners with insurers such as Aetna,

provides a score that identifies

“people

likely to participate in interventions”, and offers to predict the

progression of illnesses and intervention outcomes. According to an industry

report, the company

“ranks patients

by how much return on investment” the insurer can expect if it targets them

with particular interventions.

LexisNexis Risk Solutions, a large data

broker and risk analytics company, provides a health

scoring product that calculates health risks, as well as expected

healthcare costs for individuals, based on vast

amounts of consumer data, including purchase activities.

III. Large-scale collection and use of consumer data

Today’s

dominant online platforms – above all Google

and Facebook – have extensive information on the everyday lives of billions

of people around the globe. They are the most visible, the most pervasive, and,

aside from intelligence contractors, online advertisers, and digital fraud

detection services, perhaps the most advanced players in the personal data and analytics industry.

Many others operate behind the scenes and beyond public attention.

At its

core, online advertising consists of

an ecosystem of thousands of companies focused on constantly tracking and

profiling billions of people. Every time an ad is displayed on a website or in

a mobile app, a user’s digital profile has just been sold to the highest bidder

in the milliseconds before. In contrast to these new practices, credit reporting agencies and consumer data brokers have already

spent decades in the business of personal data. In recent years, they started

combining the extensive information they have about people’s offline lives

with the user and customer databases operated

by large platforms, online advertising companies, and myriads of

other businesses across many industries.

Data companies have extensive information on billions of people

Facebook

has profiles on

Facebook users

Google

has profiles on

Android users

Apple

has profiles on

iOS users

Experian

has credit data on

people

Equifax

has data on

people

TransUnion

has data on

people

Acxiom

has data on

people

cookies and mobile devices

it manages

consumer profiles for clients

Oracle

has data on

mobile users

provides access to

“unique” consumer IDs

Facebook uses at least 52,000

personal attributes to sort and categorize its 1.9 billion users by, for

example, their political views, ethnicity, and income. In order to do so, the

platform analyzes their posts, likes, shares, friends, photos, movements, and

many other kinds of behaviors.

In addition, Facebook acquires data on its users

from other companies. In 2013,

the platform began its partnership with the four data brokers Acxiom, Epsilon, Datalogix

and BlueKai, the latter two of which were

subsequently acquired by the IT giant Oracle. These companies help Facebook

track and profile its users even better than it already does by providing it

with data collected from beyond its platform.

IV. Data brokers and the business of personal data

Consumer data brokers play a key role in today’s personal data industry. They

aggregate, combine, and trade massive

amounts of information collected from diverse online and offline sources on

entire populations. Data brokers collect publicly available information and buy

or license consumer data from other companies. Generally, their data stems from

sources other than the individuals

themselves, and is collected largely

without consumers’ knowledge. They analyze data, make inferences, sort

people into categories, and provide thousands of attributes on individuals to

their clients.

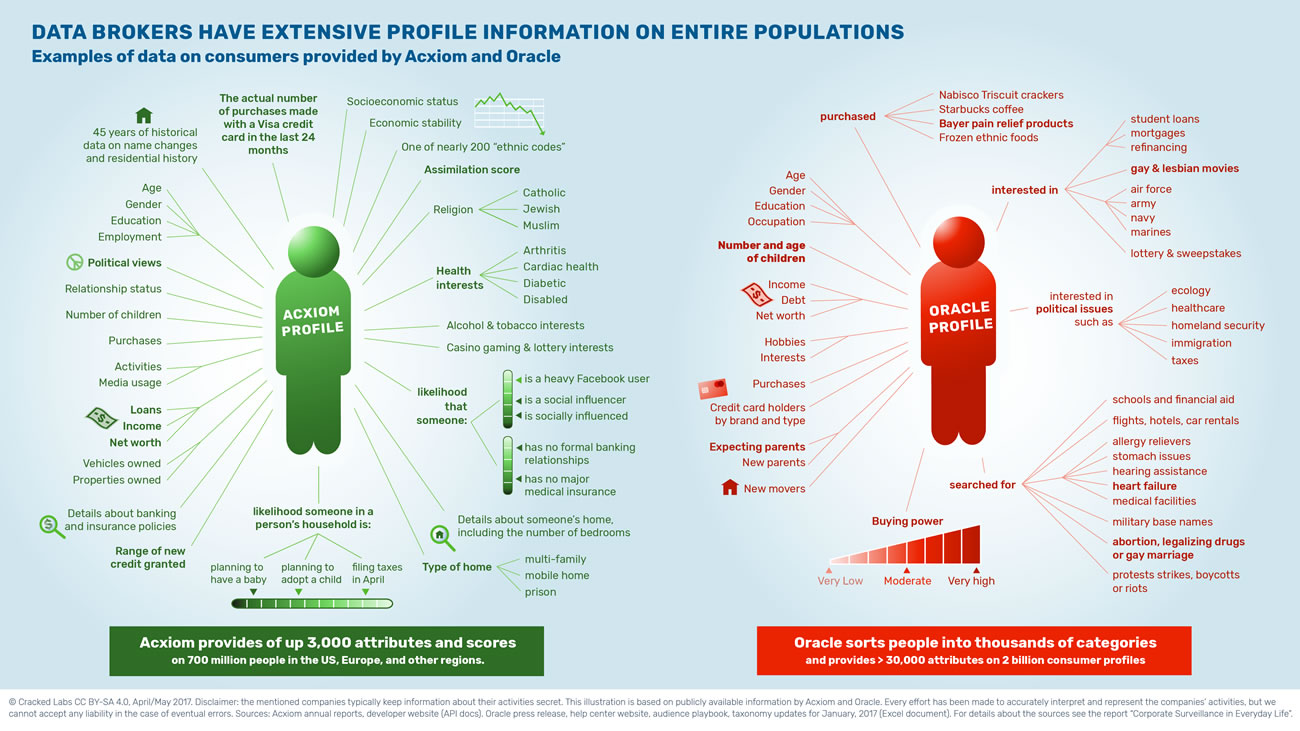

The profiles that data brokers have on individuals include not

only information about education, occupation, children, religion, ethnicity,

political views, activities, interests and media usage, but also about

someone’s online behaviors such as web

searches. Additionally, they collect data about purchases, credit card

usage, income and loans, banking and insurance policies, property and vehicle

ownership, and a variety of other data types. Data brokers also calculate scores

that predict an individual’s possible

future behavior, with regard to, for example, someone’s economic stability

or plans to have a baby or to change

jobs.

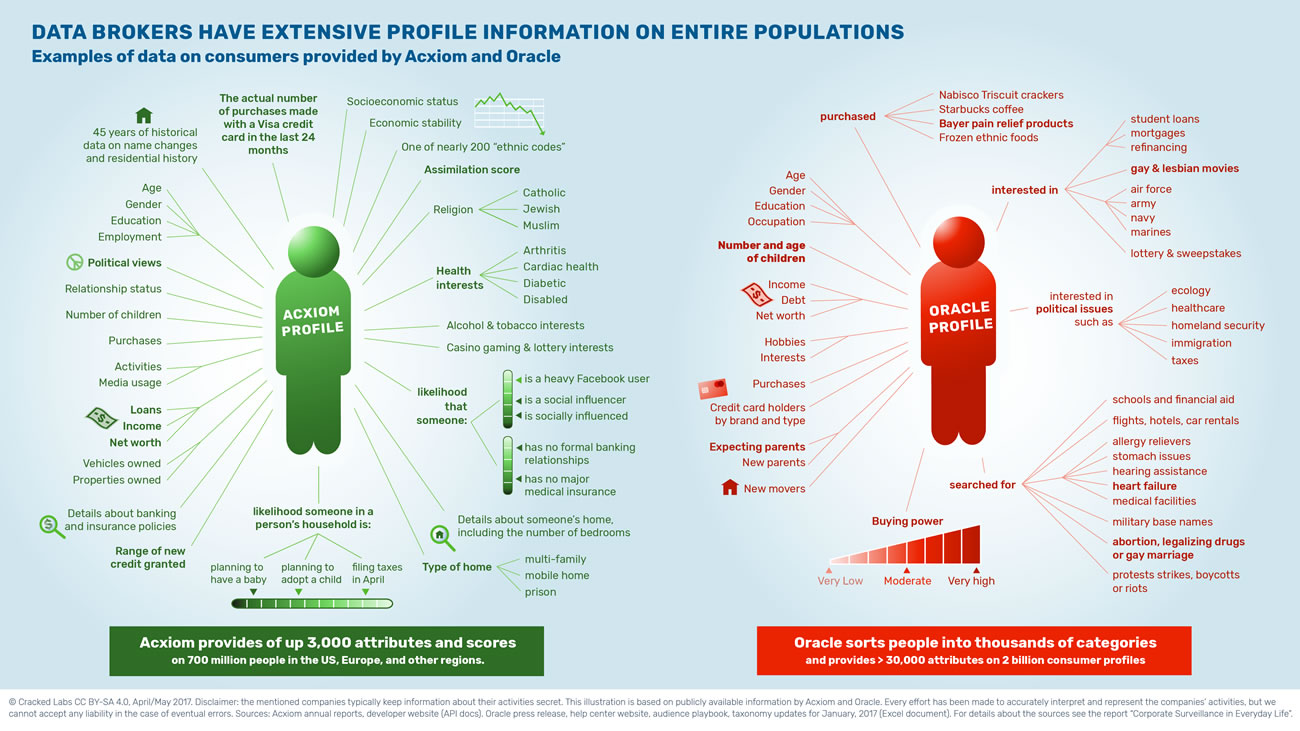

Some examples of data on consumers provided by Acxiom and Oracle

Examples of data on consumers provided by Acxiom and Oracle (as of April/May 2017). Sources see report

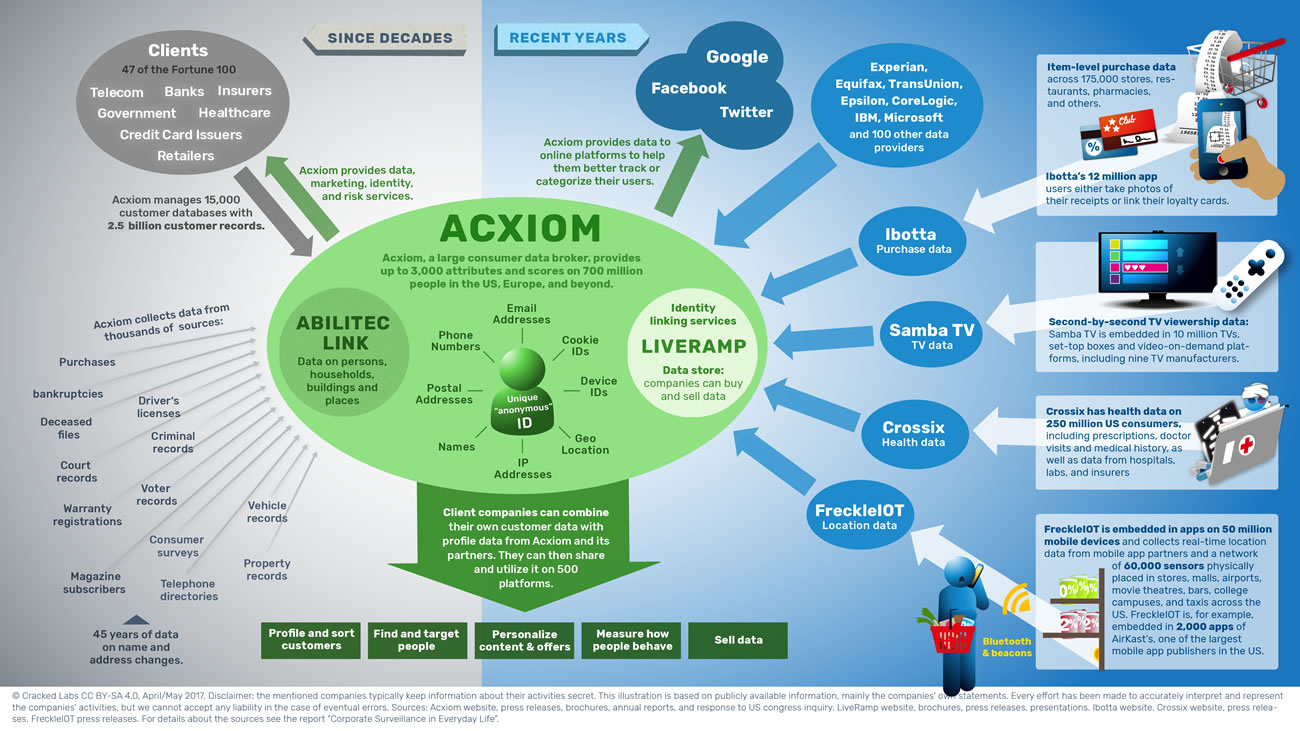

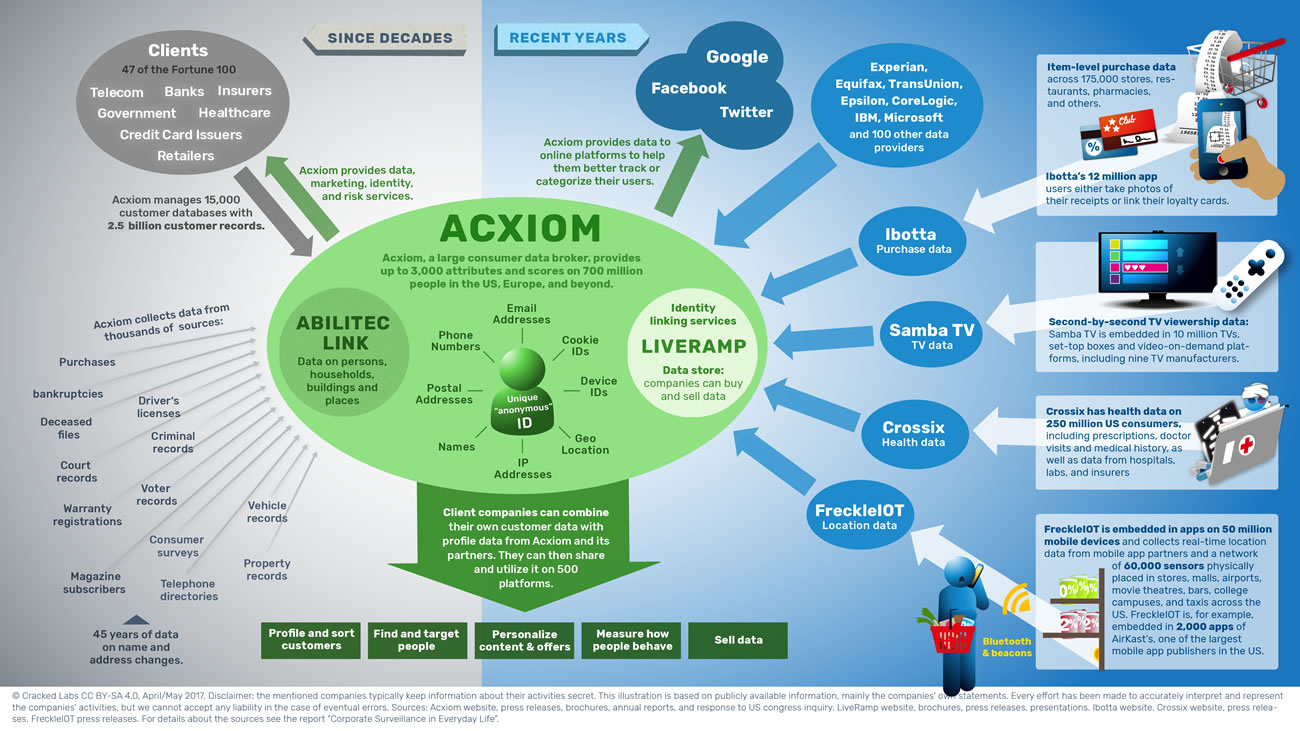

Acxiom, a large consumer data broker

Founded in

1969, Acxiom runs one of the world’s largest commercial databases on consumers.

The company provides up to 3,000

data elements on 700

million people from thousands

of sources in many countries, including the US, the UK, and Germany. Initially

a direct marketing firm, Acxiom developed its centralized consumer database in

the late 1990s.

With its Abilitec Link system

the company runs a kind of private population register in which every person,

household, and building receives a unique

ID. The company constantly updates its database with information about births and deaths, marriages and divorces,

name and address changes, and, of course all kinds of other profile data.

When asked about a person, Acxiom provides,

for example, one of 13 religious

affiliations including “Catholic”, “Jewish” and “Muslim”, and one of nearly

200 ethnic

codes.

Acxiom

sells access to its extensive consumer profiles and helps clients find, target,

identify, analyze, sort, rate, and rank people. The company also directly

manages 15,000 customer databases

with billions

of consumer profiles for its clients, including for large banks, insurers,

healthcare organizations and government agencies. Besides marketing data

services, Acxiom also provides

identity verification, risk management, and fraud detection services.

Acxiom and its data providers, partners and services

Acxiom and its data providers, partners, and clients (as of April/May 2017). Sources see report

Since the acquisition

of the online data company LiveRamp in 2014, Acxiom has made major efforts to connect

its decade-spanning data repository to the digital world. Acxiom was, for

example, among the first data brokers to provide additional information to Facebook, Google, and Twitter in order

to help the platforms better track or categorize users based on purchases and

other behaviors that the platforms were still not able to track.

Acxiom’s LiveRamp connects and combines digital profiles across hundreds of data and advertising companies.

At the core lies its IdentityLink system,

which helps recognize individuals and link information about them across databases, platforms, and devices based on email addresses, phone numbers, smartphone IDs, and other identifiers. While the company promises

that linking and matching happens in ”anonymized”

and “de-identified” ways, it also states that it is able to “connect

offline data and online data back to a single identifier”.

Companies

that have recently been promoted as data

providers by LiveRamp include the credit

reporting giants Equifax, Experian, and

TransUnion. Furthermore, many digital

tracking services that collect data from the web, mobile apps, and even sensors placed throughout the

physical world provide LiveRamp with data. Some

of them use LiveRamp’s data store, which allows

companies to “buy

and sell valuable customer data“. Others provide data to let Acxiom and LiveRamp recognize individuals and link the recorded

information with digital profiles from other sources. Perhaps most concerning

is Acxiom’s partnership

with Crossix, a company with extensive health data on 250 million US consumers. It is listed as one of LiveRamp’s

data providers.

„anyone who captures data on consumers has the potential to be a data provider“

Travis May, General Manager of Acxiom's LiveRamp,

2017

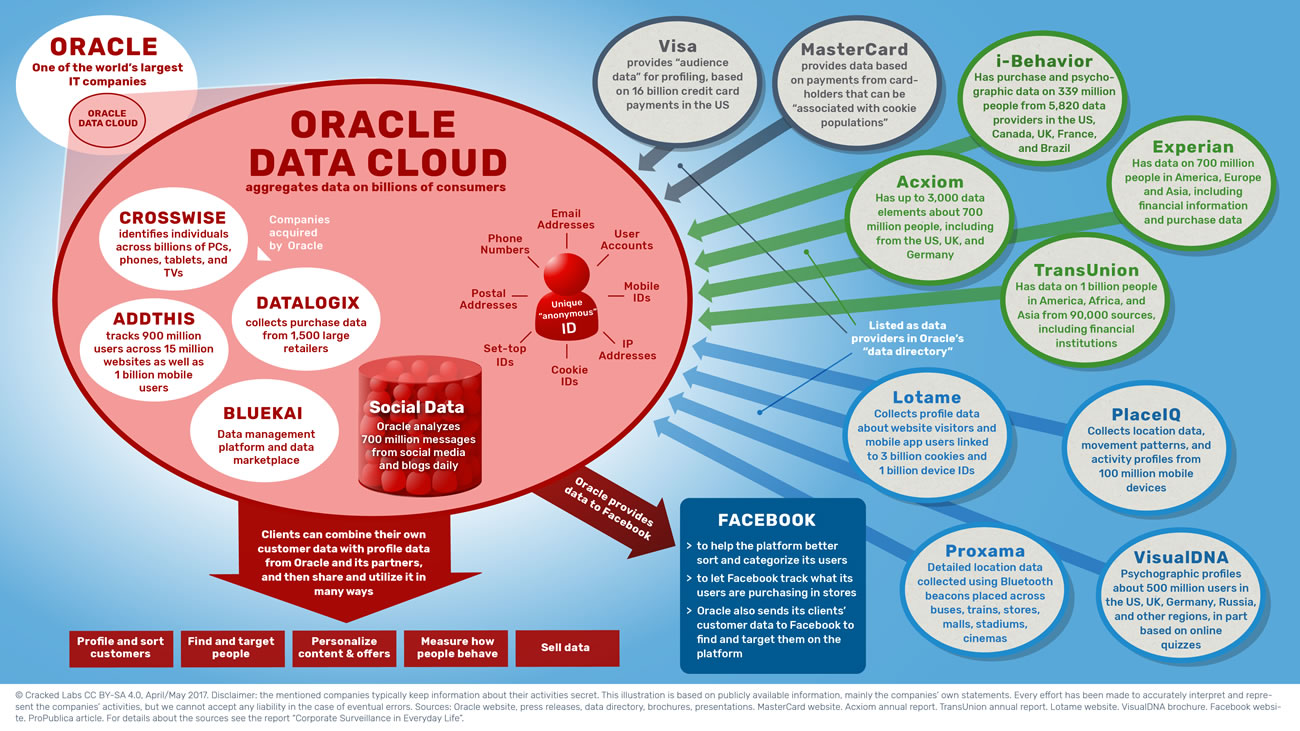

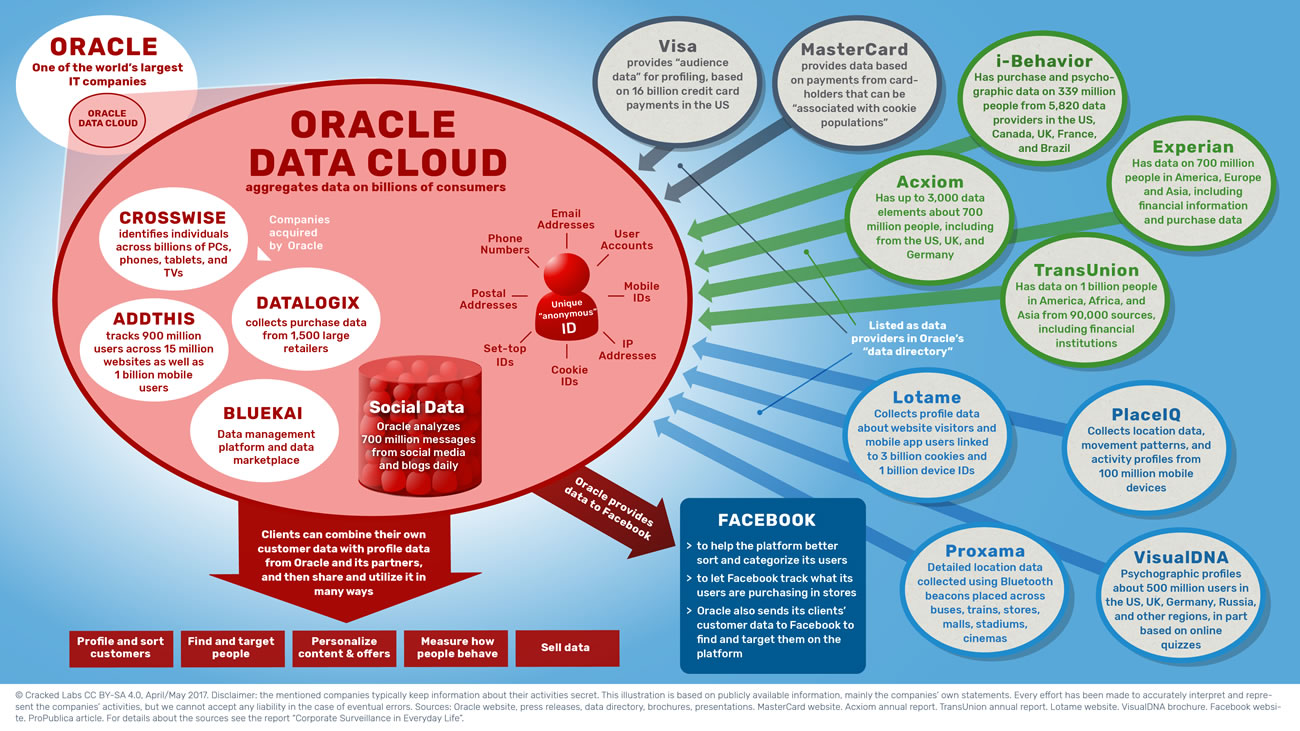

Oracle, an IT giant enters the consumer data business

By

acquiring several data companies such as Datalogix, BlueKai, AddThis, and CrossWise,

Oracle, one of the world’s largest business

software and databases vendors, has recently become one of the largest consumer data brokers as well. In its data

cloud Oracle aggregates 3

billion user profiles from 15

million different websites, data from 1

billion mobile users, billions of purchases from grocery chains and 1,500

large retailers, as well as 700

million messages from

social media networks, blogs, and consumer review sites per day.

Oracle aggregates data on billions of consumers

Oracle and its data providers, partners and services (as of April/May 2017). Sources see report

Oracle

lists nearly 100 data providers in its data

directory, including Acxiom and

credit reporting agencies such as Experian

and TransUnion, as well as companies that track website visits, mobile app

usage, and movements, or that collect data from online quizzes. Visa and MasterCard are listed as data

providers, too. Together with its partners, Oracle provides over 30,000

different data categories that may be assigned to consumers. Conversely, the

company shares data with Facebook

and helps Twitter calculate the

creditworthiness of its users.

Oracle’s ID Graph identifies and combines user profiles across

companies. It

“unites all interactions” across databases, services and devices to

“create one addressable consumer profile” and

“identify customers and prospects everywhere”. Other companies can send match

keys based on email addresses, phone

numbers, postal addresses, and other identifiers to Oracle, which will then

synchronize them to its

“network of user and statistical IDs that are linked together in the Oracle ID Graph”.

Although the company promises to only use anonymous

user IDs and anonymous

user profiles, these still refer to certain individuals and can be used to recognize

them and to single them out in many life contexts.

Generally,

clients can upload their own data about

customers, website visitors, or app users to Oracle’s data cloud, combine it with data

from many other companies and then transfer and utilize it on hundreds of other

marketing and advertising technology platforms in real-time. They can use it

to, for example, find and target

people across devices and platforms, personalize

interactions, and eventually, to measure

how consumers respond after having been addressed and affected on an

individual level.

V. Real-time monitoring of behaviors across everyday life

Online

platforms, advertising technology providers, data brokers, and businesses in

all industries can now monitor, recognize, and analyze individuals in many

situations. They are able to learn what people are interested in, what they did

today, what they are likely to do tomorrow, and how much they might be worth as

a customer.

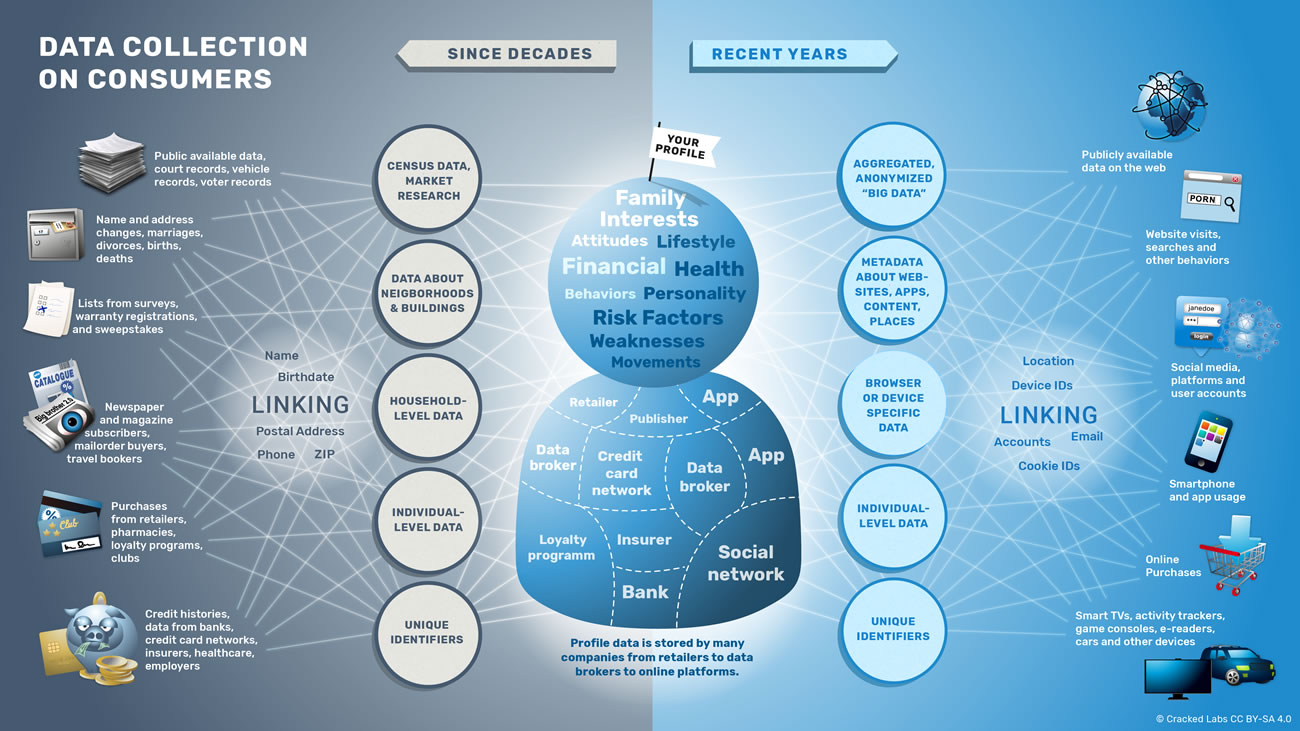

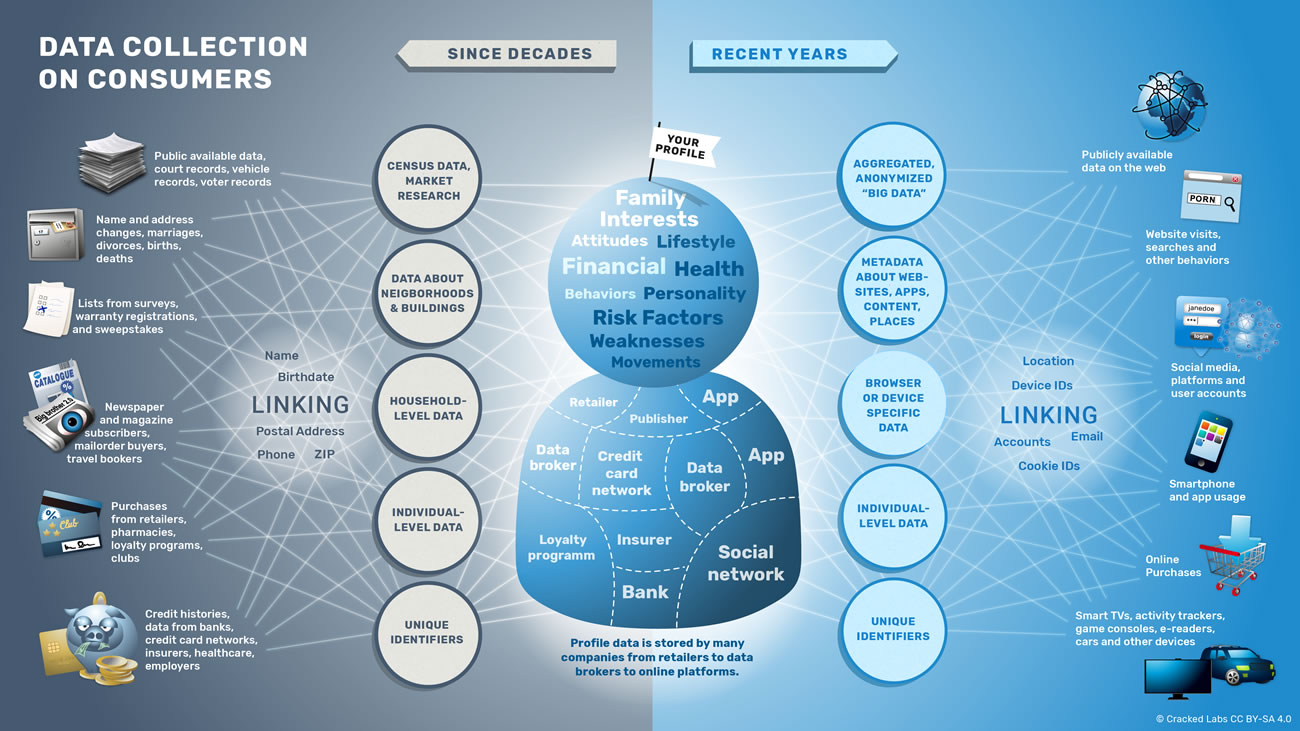

Data about people’s online and offline lives

A wide

range of companies has been collecting information on people for decades.

Before the Internet, both credit bureaus and direct marketing agencies were major points of integration between data flowing from different sources. A

first big step into systematic consumer surveillance occurred in the 1990s

through database marketing, loyalty programs, and advanced consumer credit

reporting. Following the ascent of the Internet and online advertising in the early

2000s and the rise of social networks, smartphones, and online advertising in

the late 2000s, we now see the traditional consumer data industry

integrating with the new digital tracking and profiling ecosystem in the 2010s.

Mapping data collection on consumers

Different levels, realms and sources of corporate consumer data collection.

Consumer data brokers and other firms have long been acquiring

information on newspaper and magazine subscribers, book and movie club members,

catalog and mail order buyers, travel agency bookers, seminar and conference

participants, and consumers filling out warranty card product registrations.

The collection of purchase data from loyalty

programs has also long been an established practice in this regard.

In addition

to data directly gathered from individuals they have been using, for example,

information about the types of neighborhoods and buildings people are

living in to characterize, label, sort, and categorize people. Similarly,

companies now profile consumers based on metadata about the types of

websites they surf, the videos they watch, the apps they use, and the

geographic locations they visit. In recent years, the scale and depth of

behavioral data streams generated by all sorts of everyday activities, such

as web, social media, and device usage, have risen rapidly.

„That’s No Phone. That’s My Tracker“

New York Times,

2012

Ubiquitous digital tracking and profiling

One major

reason that corporate tracking and profiling has become so pervasive lies in

the fact that nearly all websites, mobile app providers, and many device vendors

actively share behavioral data with other companies.

A few years

ago most websites began embedding

tracking services that transmit user data to third parties into their

websites. Some of these services provide visible functionality to users. When a

website shows, for example, a Facebook like button or an embedded YouTube

video, user data is transmitted to Facebook or Google. Many other services

related to online advertising remain hidden, though, and largely serve only one

purpose, namely to collect user data. It is widely unknown exactly which kinds

of user data digital publishers share and how third parties use this data.

At least

part of these tracking activities can be examined by everybody; by installing

the browser extension Lightbeam,

for example, one can visualize the hidden network third-party trackers.

A

recent study examined one million

different websites and found more than 80,000

third-party services that receive data about the visitors of these

websites. Around 120 of these tracking services were found on more than 10,000 websites, and six companies monitor users on more than 100,000 websites,

including Google, Facebook, Twitter, and Oracle’s BlueKai. A study on 200,000

users from Germany visiting 21 million web pages showed that third-party

trackers were present on 95% of the

pages visited. Similarly,

most mobile apps share information on their users with other companies. A 2015 study

of popular apps in Australia, Brazil, Germany, and the US found that between

85% and 95% of free apps and

even 60% of paid apps connect to third parties that collect personal

data.

An interactive map of hidden

third-party tracking services on Android apps created by researchers from

Europe and the US can be explored at: haystack.mobi/panopticon.

In terms of

devices, smartphones are perhaps the

biggest contributors to today’s ubiquitous data collection. The information

recorded by mobile phones provides detailed insights into a user’s personality

and everyday life. Since consumers generally need to have a Google, Apple, or Microsoft account to

use them, much of the information is already linked to a major platform’s

identifier.

Selling user data is not restricted to website and mobile app

publishers. The marketing intelligence company SimilarWeb, for example,

receives data not only from hundreds

of thousands of direct measurement sources from websites and apps, but also

from desktop

software and browser extensions. In recent years, many other kinds of

devices with sensors and network connections have entered everyday life,

from e-readers and wearables to smart

TVs, meters, thermostats, smoke alarms, printers, fridges, toothbrushes, toys,

and cars. Like smartphones, these devices give companies unprecedented

access to consumer behavior across many life contexts.

Programmatic advertising and marketing technology

The online advertising industry has become a pioneering

force in developing sophisticated technologies that monitor and track

people, as well as ones to combine and link profiles across the digital world.

Most of

today’s digital advertising takes place in the form of highly automated

real-time auctions between publishers and advertisers; this is often referred

to as programmatic advertising. When a person visits a website, it sends

user data to a variety of third-party services, which then try to recognize the

person and retrieve available profile information. Advertisers interested in

delivering an ad to this particular person due to certain attributes and

behaviors make a bid. Within milliseconds, the highest-bidding

advertiser wins and places the ad. Advertisers can similarly bid on user profiles and ad placements

within mobile apps.

For the

most part, however, this process does not take place directly between publishers and advertisers. The

ecosystem consists of a plethora of different kinds of data

and technology providers interacting with each other, including ad

networks, ad exchanges, sell-side platforms, and demand-side platforms. Some of

these specialize in tracking and advertising alongside search results,

general ads on

the web, mobile

ads, video

ads, social

network ads, or ads within games.

Others focus on providing data, analytics, or personalization services.

To profile

web or mobile app users, all parties involved have developed sophisticated

methods to accumulate, compile, and link information from different companies

in order to follow individuals across

their lives. Many of them collect or utilize digital profiles on hundreds

of millions of consumers, their web browsers, and devices.

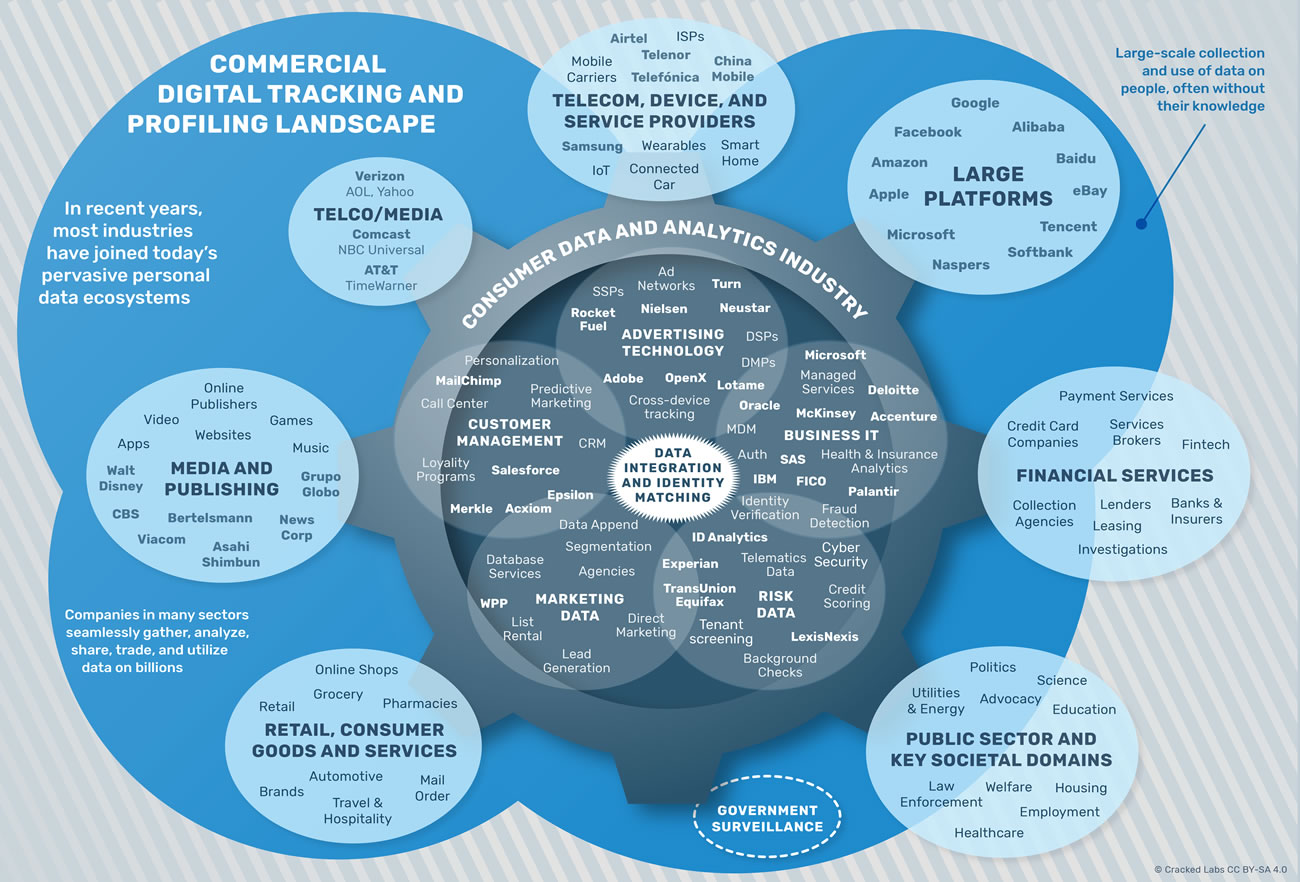

Many industries are joining the tracking economy

In recent

years, businesses in many industries have started to share and utilize data on

their users and customers at a massive scale.

Most retailers

sell more or less aggregated forms of purchase

data to market research companies and consumer data brokers. The data

company IRI, for example, accesses data from more than 85,000

grocery, mass merchandise, drug, club, dollar, convenience, liquor, and pet

stores. Nielsen states that it collects sales information from worldwide 900,000

stores in more than 100 countries.

The large

British retailer Tesco has

outsourced its loyalty and data activities to a subsidiary company, Dunnhumby,

whose slogan is “transforming

customer data into customer delight”. When Dunnhumby acquired the German ad

technology company Sociomantic, they announced

that Dunnhumby will “combine its extensive insights on the shopping preferences

of 400 million consumers” with Sociomantic’s “real-time data from more than 700

million online consumers” to personalize and evaluate advertising.

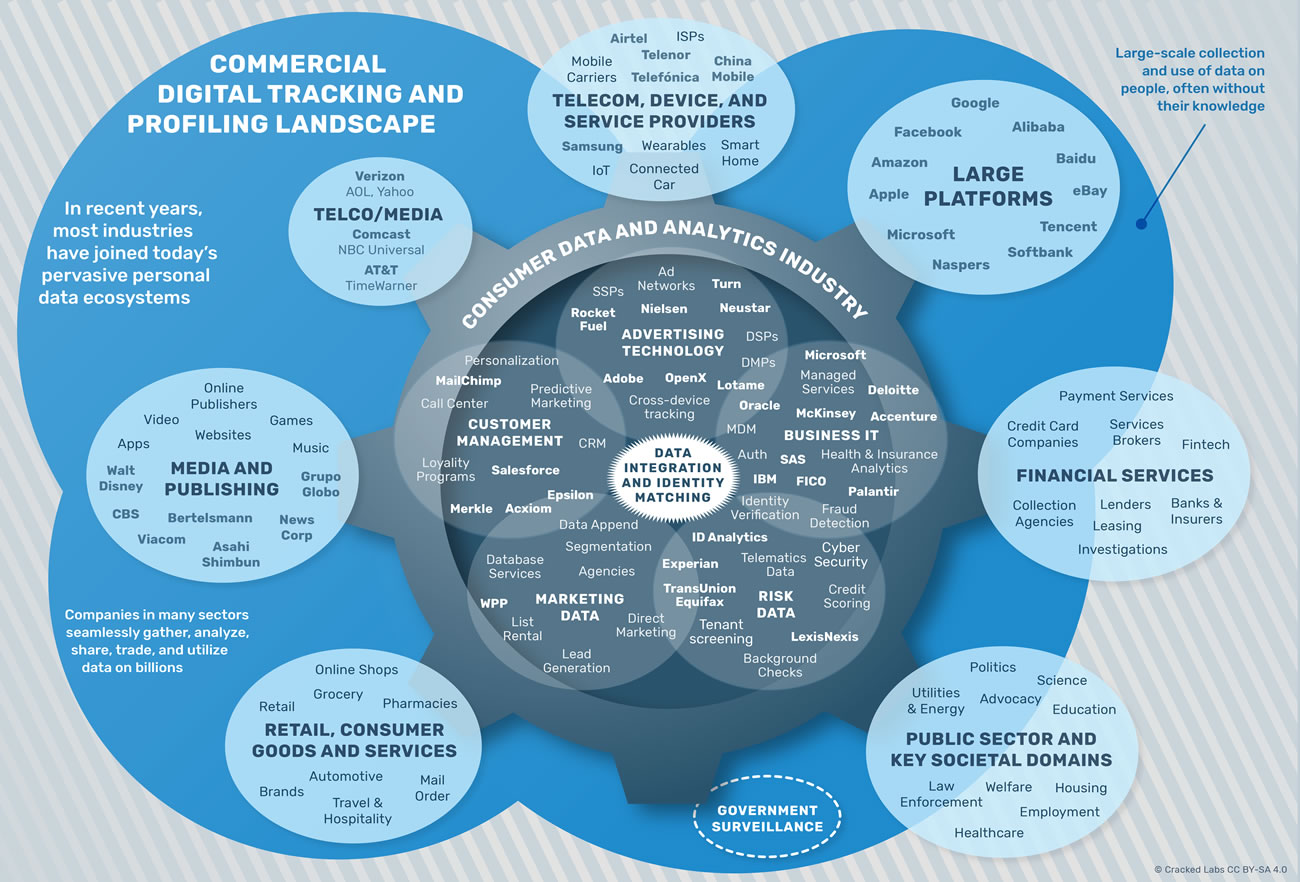

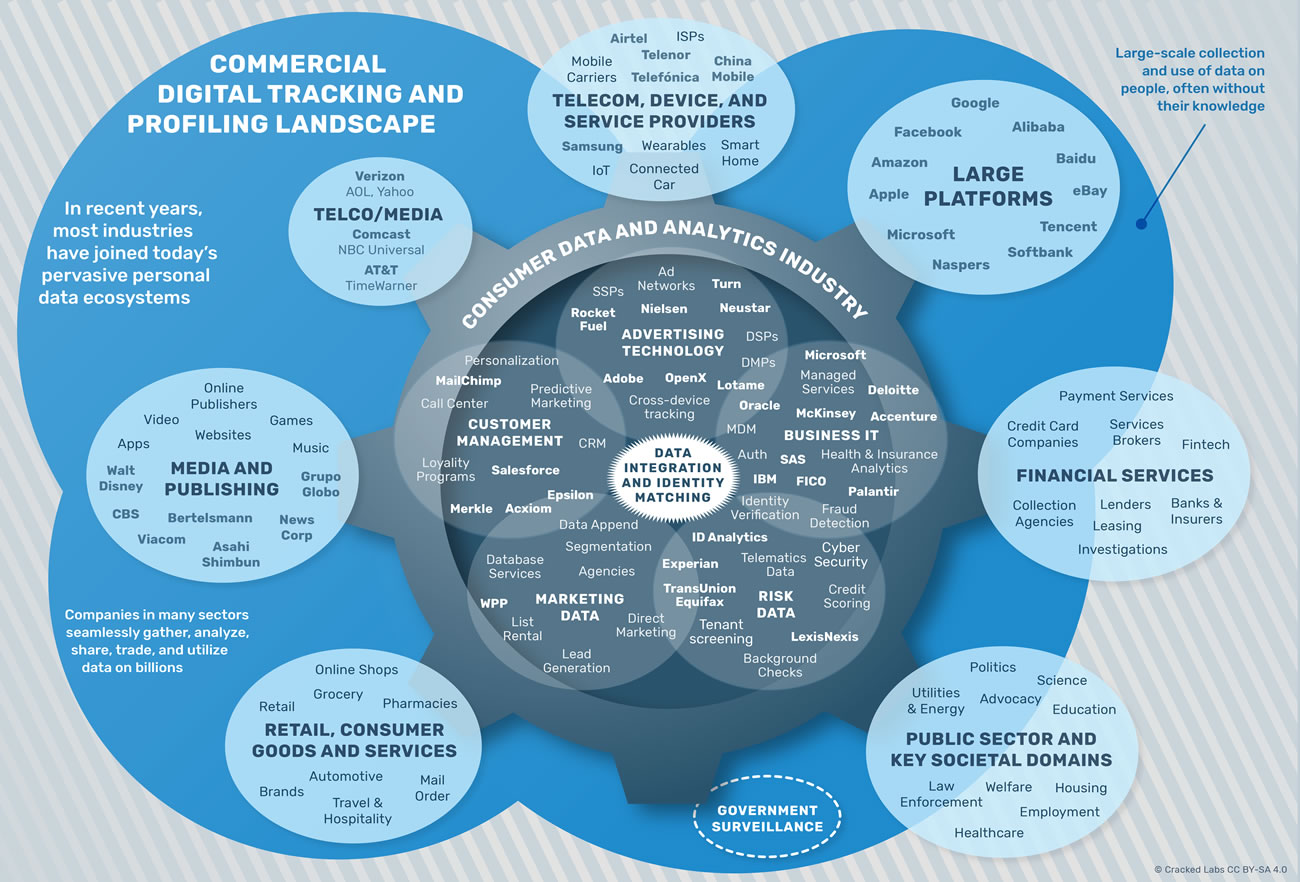

Mapping the commercial digital tracking and profiling landscape

In addition to the large online platforms and the consumer data and analytics industry, businesses in

many industries have joined today’s pervasive digital tracking and profiling ecosystems

Large media

conglomerates are also deeply embedded in today’s tracking and profiling

ecosystems. For example, Time Inc.

has acquired Adelphic,

a major cross-device tracking and ad technology company, as well as Viant, a

company that claims to have access

to over 1.2 billion registered users. A prominent example of a digital

publisher that sells data on its users is the streaming platform Spotify. Since 2016, it shares insights

on their users’ mood, listening and playlist behavior, activity and location

with the data division of the advertising giant WPP, which now has access to

“unique listening preferences and behaviors of Spotify’s 100 million users”.

Many large telecom

companies and Internet Service Providers have acquired ad technology and

data companies. For example, Millennial Media, a subsidiary of Verizon’s AOL, is a mobile ad platform

collecting data from more than 65,000 apps from different developers, and

claims to have access

to approximately 1 billion global active unique users. The Singapore-based

telecom corporation Singtel acquired

Turn, an ad technology platform that gives marketers access to 4.3 billion addressable device

and browser IDs and 90,000

demographic, behavioral, and psychographic attributes.

Like

airlines, hotels, retailers and companies in many other industries, the financial

services sector started to aggregate and utilize additional customer

data with loyalty programs in the 1980s and 1990s. Companies with related,

complementary target groups have long been sharing certain customer data with

each other, a process often managed by intermediaries. Today, one of these

intermediaries is Cardlytics, a firm that runs reward programs with 1,500 financial

institutions such as the Bank of America

and MasterCard. Cardlytics promises

financial institutions that it will “generate new revenue streams using the

power of [their] purchase data”. The company also partners with LiveRamp, the

Acxiom subsidiary that combines

online and offline consumer data.

For MasterCard, selling products and

services created from data analytics might even become its core business given that information

products, including sales of data already represent a considerable and

growing share of its revenue. Google

recently stated that it captures approximately

70% of credit and debit card transactions in the United States through “third-party

partnerships” in order to track purchases, but did not disclose its sources.

„It’s your data. You have the right to control it, share it and use it how you see fit.“

How the online data broker Lotame addresses its corporate clients on its website,

2016

VI. Linking, matching and combining digital profiles

Until

recently, advertisers who used Facebook, Google or other online ad networks

could target individuals based only on their online behavior. However, a few years

ago data companies began providing ways to combine and link digital profiles

across platforms, customer databases, and the world of online advertising.

Connecting online and offline identities

In 2012, Facebook started allowing companies to upload

their own lists of email addresses and phone numbers to the platform. Although

these addresses and numbers are converted into pseudonymous

codes, Facebook can directly link this customer data from other companies

with Facebook user accounts. In this way, companies can, for example, find and target exactly those persons

on Facebook that they have email addresses or phone numbers on. They could also

selectively exclude them from targeting or let the platform find people with

similar attributes, interests, and behaviors.

This is a powerful feature, perhaps more powerful

than it seems at first glance. It allows companies to systematically connect

their own customer data with Facebook’s data. Moreover, it also allows other

advertising and data vendors to synchronize with the platform’s databases and

tap into its capacities, essentially providing a kind of real-time remote control for Facebook’s data universe. Companies

can now capture highly specific behavioral data, such as a click on a website,

a swipe in a mobile app or a purchase in a store, in real-time, and tell

Facebook to immediately find and target the persons who performed these

activities. Google

and Twitter

launched similar features in 2015.

Data management platforms

Today, most

advertising technology companies continuously pass various forms of

codes referring to individuals onto each other. Data management platforms allow

businesses in all industries to combine

and link their own data on consumers, including real-time information about

purchases, website visits, app usage, and email responses, with digital profiles provided by myriads third-party data

providers. The combined data can then be analyzed, sorted and categorized, and

used to address certain people with certain messages on certain channels or

devices. A company could, for example, target a group of existing customers

that visited a certain page on its website, and are predicted to become valuable customers, with personalized content

or a discount – either on Facebook, in a mobile app, or on the company’s own

website.

The

emergence of data management platforms marks a key moment in the development of pervasive commercial behavioral tracking. With

their help, businesses in all industries across the globe are able to

seamlessly combine and link the data they have collected about their customers

and prospects for years with billions of profiles collected within the world of

digital tracking. Companies running such platforms include

Oracle, Adobe, Salesforce (Krux), Wunderman (KBM Group/Zipline), Neustar,

Lotame, and Cxense.

„We will serve ads to you based on your identity, but that doesn't mean you're identifiable“

Erin Egan, chief privacy officer at Facebook,

2012

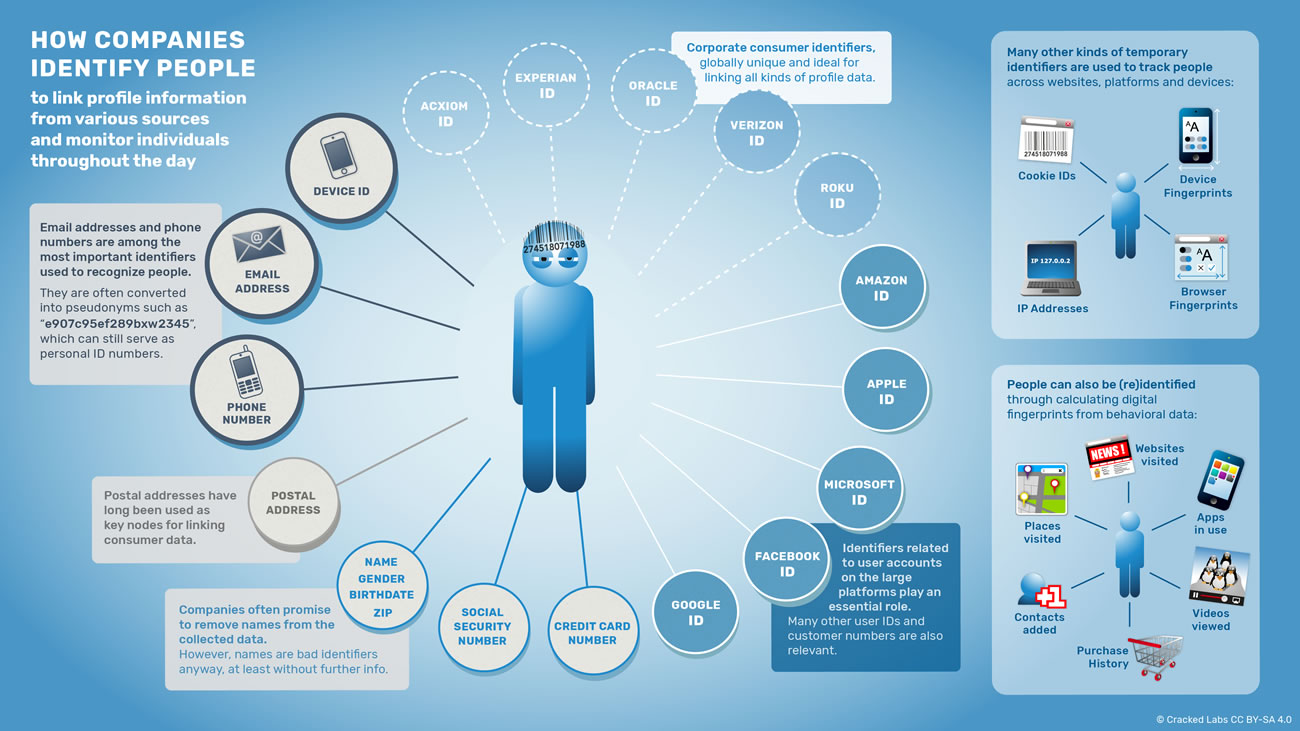

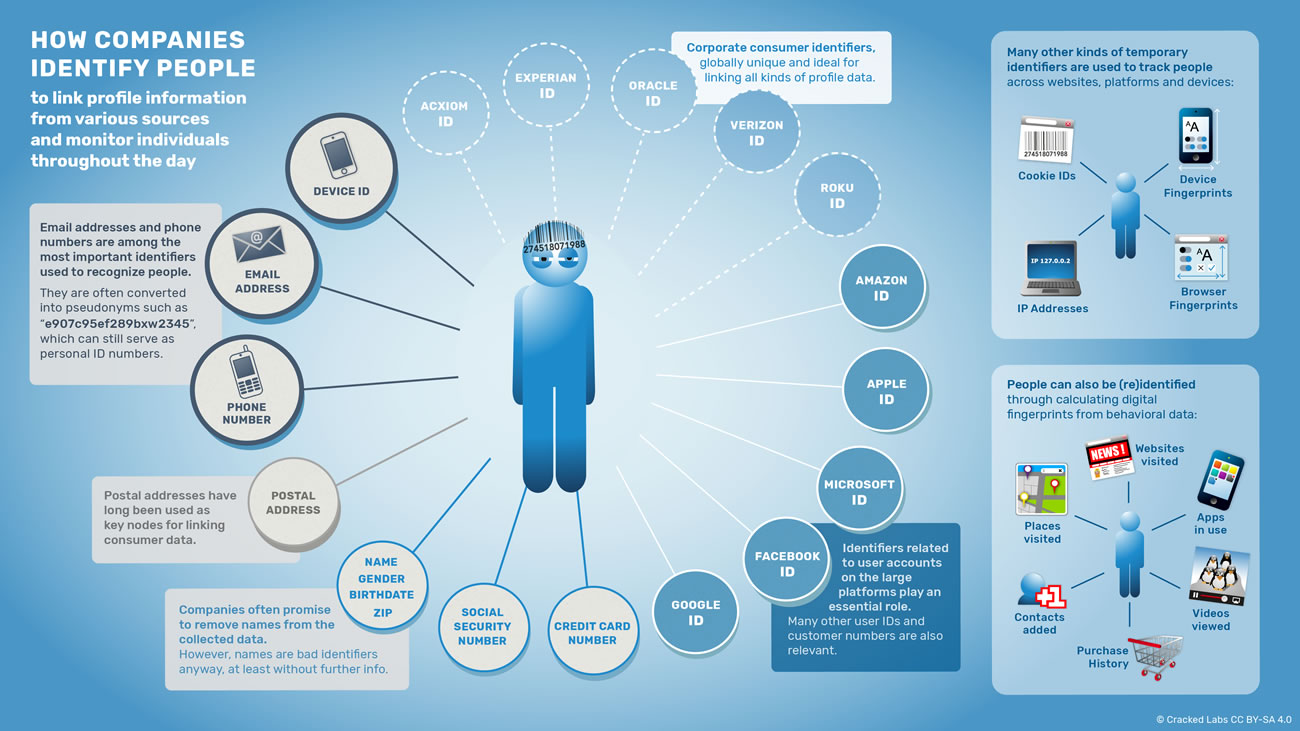

Identifying people and linking digital profiles

To monitor

and follow people in many situations of their lives, combine profiles on them,

and always recognize them as the same individuals again, companies collect a wide

range of data attributes that identify them in some way.

Because of

its ambiguity a person's legal name has always been a bad identifier for data collection.

The postal address, in contrast, has

long been, and still is, a key attribute that allows combining and linking data

about consumers and their families from different sources. In the digital

world, the most relevant identifiers used to link profiles and behavioral data

across different databases, platforms, and devices are email addresses, phone numbers, and unique codes that refer to

smartphones or other devices.

User account IDs of the large platforms such as Google,

Facebook, Apple, and Microsoft also play an important role in following people

across the Internet. Google, Apple, Microsoft,

and Roku

assign “advertising IDs” to

individuals, which are now widely used to match and link data from devices

such as smartphones with other information from all over the digital world. Verizon

uses its own identifier to track users across websites and devices. Some large

data companies such as Acxiom, Experian,

and Oracle have introduced globally

unique IDs for people, which they use to link their decades-old consumer

databases and other profile information from different sources with the digital

world. These corporate IDs mostly

consist of two or

more identifiers that are attached to different aspects of the online and

offline life of someone and can be linked to each other in certain ways.

Identifiers used to track people across websites, devices and areas of life

How companies identify consumers and link profile information about them. Sources see report

.

Tracking

companies also use more-or-less temporary identifiers, such as cookie IDs

that are attached to users surfing the web. Since users may disallow or delete

cookies in their web browser, they have developed sophisticated methods to

calculate unique digital fingerprints

based on various attributes of someone’s web browser and computer. Similarly,

companies compile fingerprints for devices such as smartphones. Cookie

IDs and digital fingerprints are constantly

synchronized between different tracking services, and then linked with

other, more permanent identifiers.

Other

companies provide cross-device tracking services that are based on using

machine learning to analyze large amounts of data. For example, Tapad, which has been acquired by the

Norwegian telecom giant Telenor, analyzes data on 2

billion devices around the globe and uses behavioral and relationship-based

patterns to find the statistical chance that certain computers, tablets,

phones and other devices belong to the same person.

“Anonymous” profiling?

Data

companies often remove names from their extensive profiles and use hashing

to convert email addresses and phone numbers into alphanumeric codes such as “e907c95ef289”. This allows them to

claim on their websites and in their privacy policies that they only collect,

share, and use “anonymized” or “de-identified” consumer data.

However,

because most companies use the same deterministic processes to calculate these

unique codes, they should be understood as pseudonyms that are,

in fact, much more suitable for identifying consumers across the digital world

than real names. Even if the profiles companies share with one another only contain “hashed” or

“encrypted” email addresses and phone numbers with each other, a person can still be recognized again

as soon as he or she uses another service linked with the same email address or

phone number. In this way, even though each of the tracking services involved

might only know a part of someone’s profile information, companies can follow and interact with people at an

individual level across services, platforms, and devices.

„If a company can follow and interact with you in the digital environment – and that potentially includes the mobile phone and your television set – its claim that you are anonymous is meaningless, particularly when firms intermittently add offline information to the online data and then simply strip the name and address to make it ‘anonymous’.“

Joseph Turow, marketing and privacy scholar in his book “The Daily You”, 2011

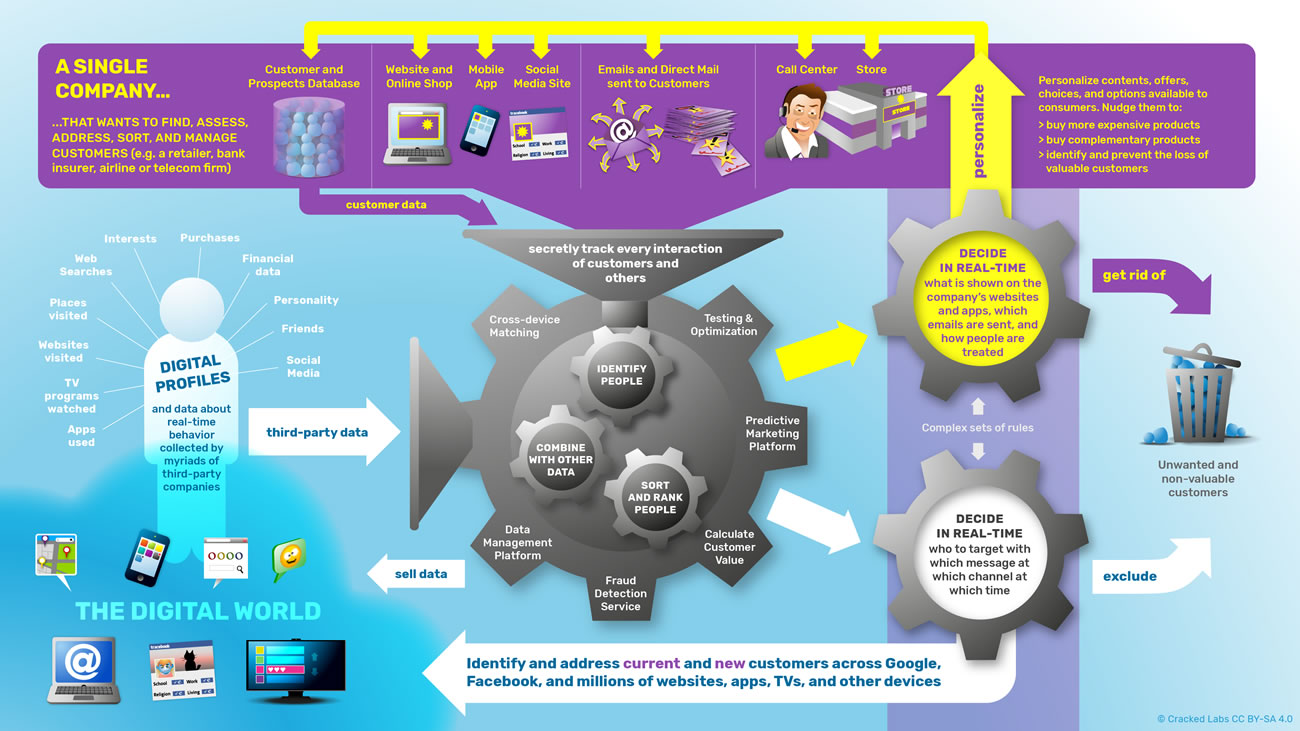

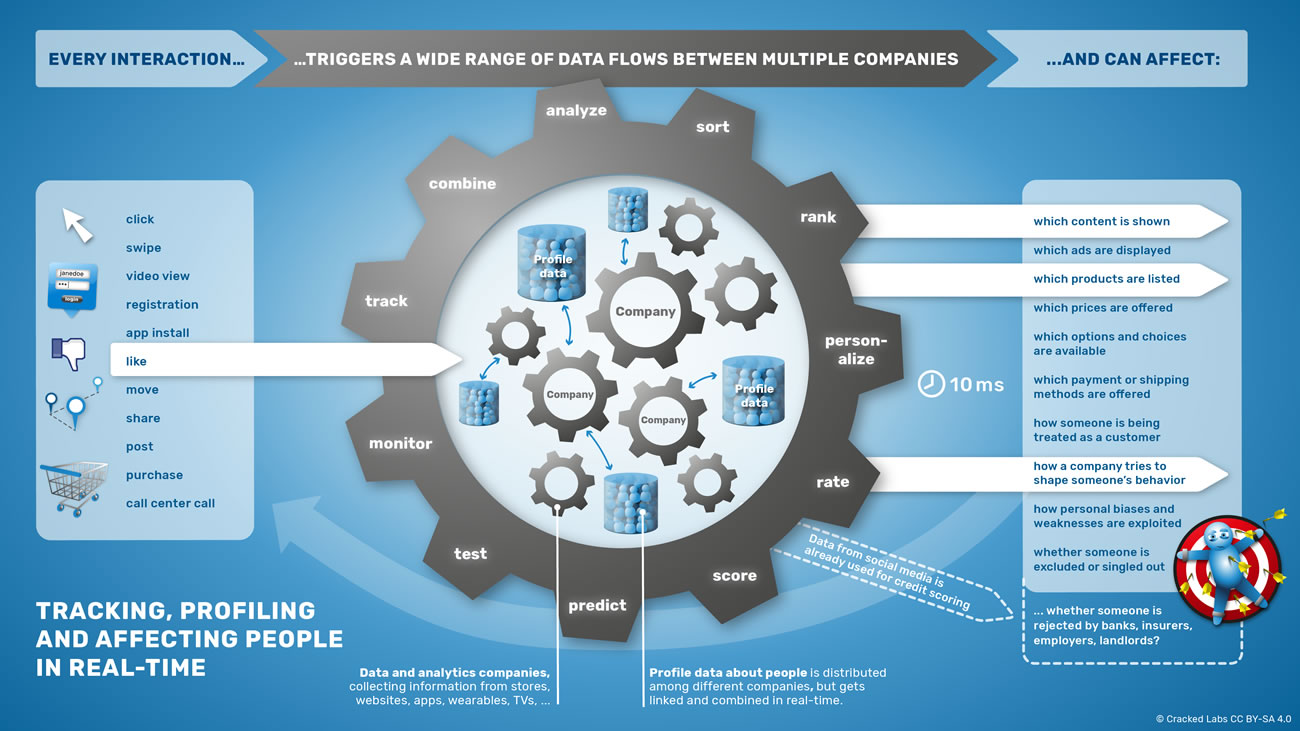

VII. Managing consumers and behaviors, personalization and testing

Based on

the sophisticated methods of linking and combining data across different

services, businesses in all industries can utilize today’s ubiquitous

behavioral data streams to monitor and analyze a wide range of consumer

activities and behaviors that might be relevant to their business interests.

With the

help of data vendors, companies try to capture as many touchpoints

across the whole customer

journey as possible, from digital ones to in-store purchases, direct mail,

TV ads, and call center calls. They try to record

and measure every interaction with a consumer, including on websites,

platforms, and devices they do not control themselves. They can seamlessly

collect rich data about their customers and others in real-time, enhance

them with information from third parties, and utilize the enriched

profiles within the

marketing and ad technology ecosystem. Today’s consumer data management platforms allow

for the definition of complex sets of

rules that dictate how to automatically react to specific criteria such as

certain activities, people, or some combination thereof.

Consequently,

individuals never know whether their

behavior triggered a reaction from any of these continuously updated,

interconnected, opaque networks of tracking and profiling, and, if so, how this

affects the options they get across communication channels and life situations.

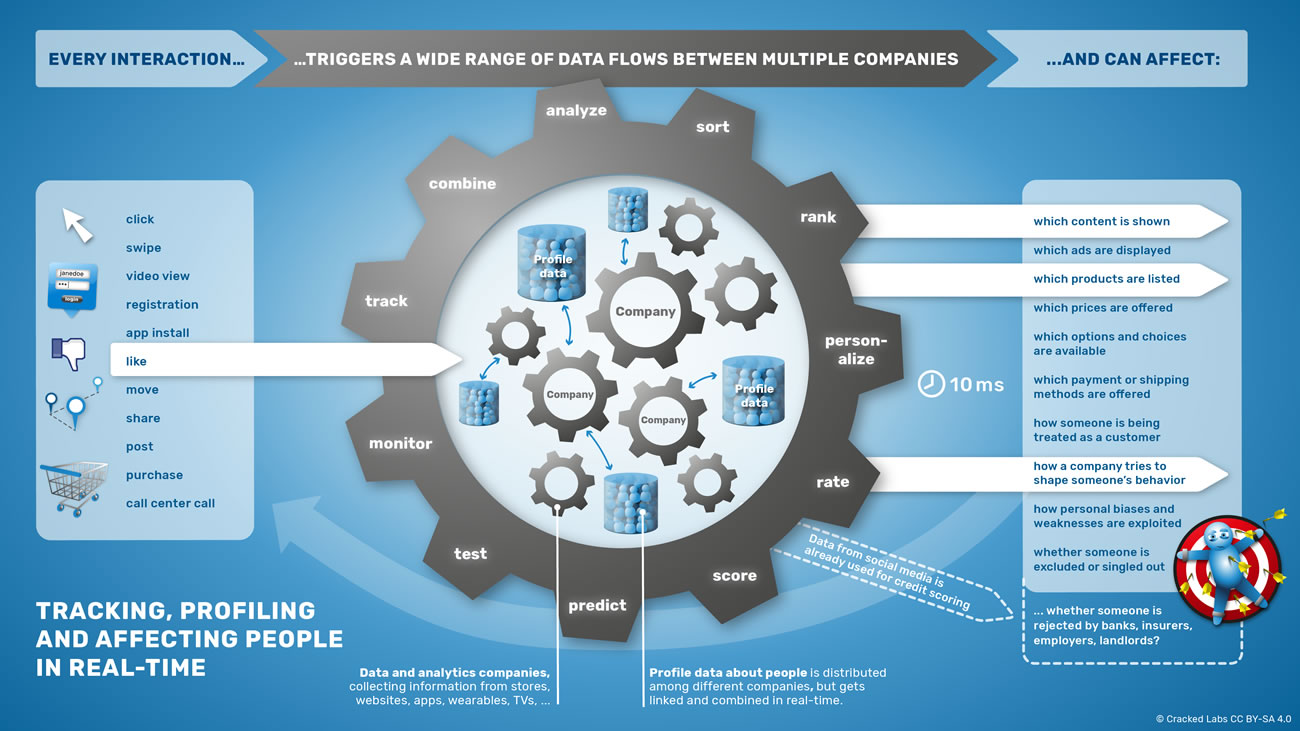

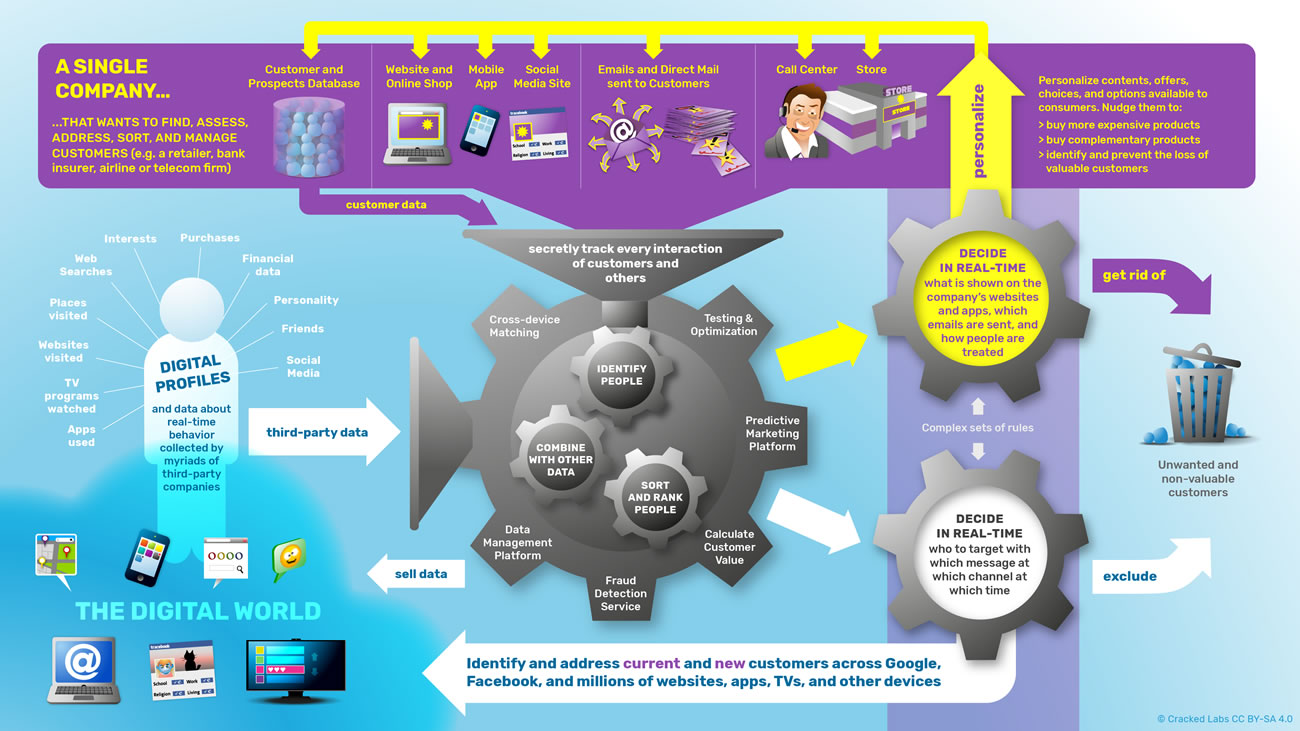

Tracking, profiling and affecting people in real-time

Every interaction triggers a wide range of data flows between multiple companies.

Mass personalization

The data

streams that are shared between online advertisers, data brokers, and other

companies are not only used to display precisely targeted ads on websites or

within mobile apps to users. They are increasingly used to dynamically personalize the contents, options, and

choices offered to consumers on, for example, a company’s website. The data

technology firm Optimizely, for instance, can help personalize a website for first time

visitors, based on digital profiles on those visitors provided by Oracle.

Online

stores might, for example, personalize how someone is addressed, which products are displayed

prominently, which discounts are

offered, and even the prices of products or services can differ based on who is

visiting a website. Online fraud detection services assess users in real-time

and decide which payment and shipping

methods someone sees.

Companies have developed technologies to constantly calculate and rate

someone’s potential long-term

value based on information about a said person’s

browsing, search, and location history, as well as app usage, product purchases, or friends on a social network.

Every

click, swipe, like, share, or purchase might automatically influence how someone is treated as a customer,

how long someone has to wait when calling a phone hotline, or whether someone

is excluded from marketing efforts or services at all.

„The rich see a different Internet than the poor“

Michael Fertik, founder of reputation.com,

2013

Three types of technology platforms play an important role for this

kind of instant personalization. First, companies use advanced Customer

Relationship Management systems to manage their data on

customers and prospects. Second, they use Data

Management Platforms to connect their own data to the digital

advertising ecosystem, and gain additional profile information about their

customers. Third, they can use Predictive Marketing Platforms, which

help them compile the right

message to the right person at the right time by calculating how to persuade

someone by exploiting personal biases and weaknesses.

The data

company RocketFuel, for example, promises its clients to “bring

together trillions of digital and real-world signals to create individual

profiles and deliver personalized, always-on, always-relevant experiences to

the consumer”, based on 2.7 billion unique

profiles in its data store. RocketFuel says that it “scores

every impression for its propensity to influence the consumer”.

The

predictive marketing platform TellApart,

which belongs to Twitter, creates a customer value score

for each shopper and product combination, a “compilation of likelihood to

purchase, predicted order size, and lifetime value”, based on “100s of online

and in-store signals about a particular anonymous customer”. Subsequently,

TellApart helps automatically assemble content such as “product imagery, logos,

offers and any metadata” for personalized ads, emails, websites, and offers.

Personalized pricing and election campaigns

Similar

methods can be used to personalize prices in online shops by, for example,

predicting how valuable someone might be as customer in the long term or

how much someone is probably willing to pay in a moment. Strong evidence suggests

that online shops already show differently

priced products to different consumers, or even different prices for the

same products, based on their individual characteristics and behaviors.

A similar field is the use of personalization during election campaigns. Targeting voters with personalized

messages that are

adapted to their personality and to their political views on certain issues has

already raised massive

debates about the potential for political

manipulation.

Utilizing data, analytics, and personalization to manage consumers

Businesses in all industries can utilize today’s networks of digital tracking and profiling

to find, assess, address, sort and manage customers.

Testing and experimenting on people

Personalization

based on rich profile information and pervasive real-time monitoring has become

a powerful tool set to influence

consumer behavior such as visiting a website, clicking on an ad,

registering for a service, subscribing to a newsletter, downloading an app, or

purchasing a product.

To further

improve this, companies have started continuously experimenting on people. They

conduct tests with different variations of functionalities, website designs,

user interface elements, headlines, button texts, images, or even different

discounts and prices, and then carefully monitor and measure how different

groups of users interact with these variations. In this way, companies systematically optimize their ability to

nudge people into acting how they want them to act.

News

organizations, including large outlets such as the Washington

Post, use different versions of

article headlines to test which variant performs better. Optimizely, one of

the major technology providers for such tests, offers its clients the ability to

“experiment broadly across the entire customer experience, on any channel, any

device, and any application”. Experimenting on unaware users has become the new normal.

Facebook stated

in 2014 that it runs “over a thousand experiments each day” in order to

“optimize specific outcomes” or “inform long-term design decisions”. In 2010 and 2012,

the platform conducted experiments on millions of users and showed that manipulating

Facebook’s user interface, functionalities, and displayed content can significantly increase voter turnout

for groups of people. The platform’s notorious mood experiment on

nearly 700,000 users involved secretly manipulating the amount of emotionally

positive and negative posts in users’ news feeds, which ended up influencing how many emotionally positive

and negative messages the users then posted themselves.

After

massive public criticism of Facebook’s experiments, the online dating platform OkCupid released a provocative blog

post defending such practices, stating that “we experiment on human beings”

and “so does everybody else”. OkCupid reported on an experiment wherein they

had manipulated the “match” percentage shown to pairs of users. When they

showed a 90% match to actually bad-matching pairs, these users exchanged

significantly more messages with each other. OkCupid claimed that when they

“tell people” they are a “good match”, they “act as if they are”.

All these

ethically highly questionable experiments clearly demonstrate the power of data-driven personalization to influence behavior.

VIII. Dragnet – everyday life, marketing data and risk analytics

Data about

people’s behaviors, social relationships, and most private moments is

increasingly applied in contexts or for purposes completely different from

those for which it was recorded. In particular, it is increasingly used to make

automated decisions about individuals

in crucial areas of life such as finance, insurance, and healthcare.

Risk data for marketing and customer management

Credit

reporting agencies and other key

players in risk assessment in fields such as identity verification, fraud

prevention, healthcare and insurance analytics mostly also provide marketing

solutions. Furthermore, most consumer data brokers trade many kinds of

sensitive information – e.g. about an individual’s financial situation – for

marketing purposes. The use of credit scores for marketing purposes to either

focus on or exclude vulnerable population groups has evolved into products that

unify marketing and risk management.

The credit

reporting agency TransUnion

provides, for example, a product for data-driven

decisions in retail and financial services that allows clients to

“implement marketing and risk strategies tailored for customer, channel and

business goals”, including credit

data and promising “unique insights into consumer behavior, preferences and

risk”. Companies can let consumers “choose from a suite of offerings that are

tailored to their needs, preferences and risk profile” and “evaluate a customer

for multiple products across channels, and then only present the offer(s) that

are most relevant to them, and profitable” for the company. Similarly, Experian provides a product

that combines “consumer credit and marketing information that is compliantly

available from Experian”.

„Surveillance is not about knowing your secrets, but about managing populations, managing people“

Katarzyna Szymielewicz, Vice-President EDRi,

2015

Online identity verification and fraud detection

In addition

to the real-time surveillance machine that has been developed within online

advertising, another forms of pervasive

tracking and profiling has emerged in the fields of risk analytics, fraud detection and cyber security.

Today’s online

fraud detection services use highly invasive technologies to evaluate billions of digital transactions

and collect vast amounts of information about devices, individuals, and

behaviors. Traditional vendors in credit reporting, identity verification,

and fraud prevention have started to monitor and evaluate how people surf the

web and use their mobile devices. Furthermore, they have started to link digital behavioral data with the vast

amounts of offline identity information that they have been collecting for

decades.

With the

rise of technology-mediated services, verifying consumer identities and

preventing fraud have both become increasingly important and challenging

issues, especially in light of cybercrime and automated fraud. At the same

time, today’s risk analytics systems have aggregated giant databases with sensitive information on entire populations.

Many of these systems cover a wide range of use cases, including proof of

identity for financial services, assessing insurance and benefits claims,

analyzing payment transactions, and evaluating billions of online transactions.

Such risk

analytics systems may decide whether an application or transaction is accepted or rejected or which payment

and shipping options are available for someone during an online transaction.

Commercial services for identity verification and fraud analytics are also used

in areas such as law enforcement and

national security. The line between commercial applications of identity and

fraud analytics and those used by government intelligence services is blurring more and more.

When people

are singled out by such opaque systems, they might get flagged as suspicious and warranting special treatment or investigation

– or they may be rejected without explanation. They might get an email, a phone

call, a notification, an error message, or the system may simply withhold an

option without the user ever knowing of its existence for others. Inaccurate

assessments may spread from one system to another. It is often difficult or impossible to object to

such negative assessments that exclude or deny, especially because of how hard

it is to object to mechanisms or decisions that someone does not know about at

all.

Examples of online fraud detection and risk analytics services

The cyber

security firm ThreatMetrix processes data on 1.4

billion “unique user accounts” across “thousands of global websites”. Its Digital Identity

Network captures “millions of daily consumer transactions including logins,

payments and new account originations”, and maps the “ever-changing

associations between people and their devices, locations, account credentials,

and behavior” for identity verification and fraud prevention purposes. The

company partners with

Equifax and TransUnion. Its clients include Netflix,

Visa,

and firms in fields such as gaming, government services, and healthcare.

Similarly,

the data company ID Analytics, which was recently acquired by Symantec,

runs an ID

Network with “100 million identity elements coming in each day from leading

cross-industry organizations”. The company aggregates data on 300 million

consumers, including on

sub-prime loans, online purchases and credit card and wireless phone

applications. Its ID

Score evaluates digital devices, as well as names, social security numbers,

and postal and email addresses.

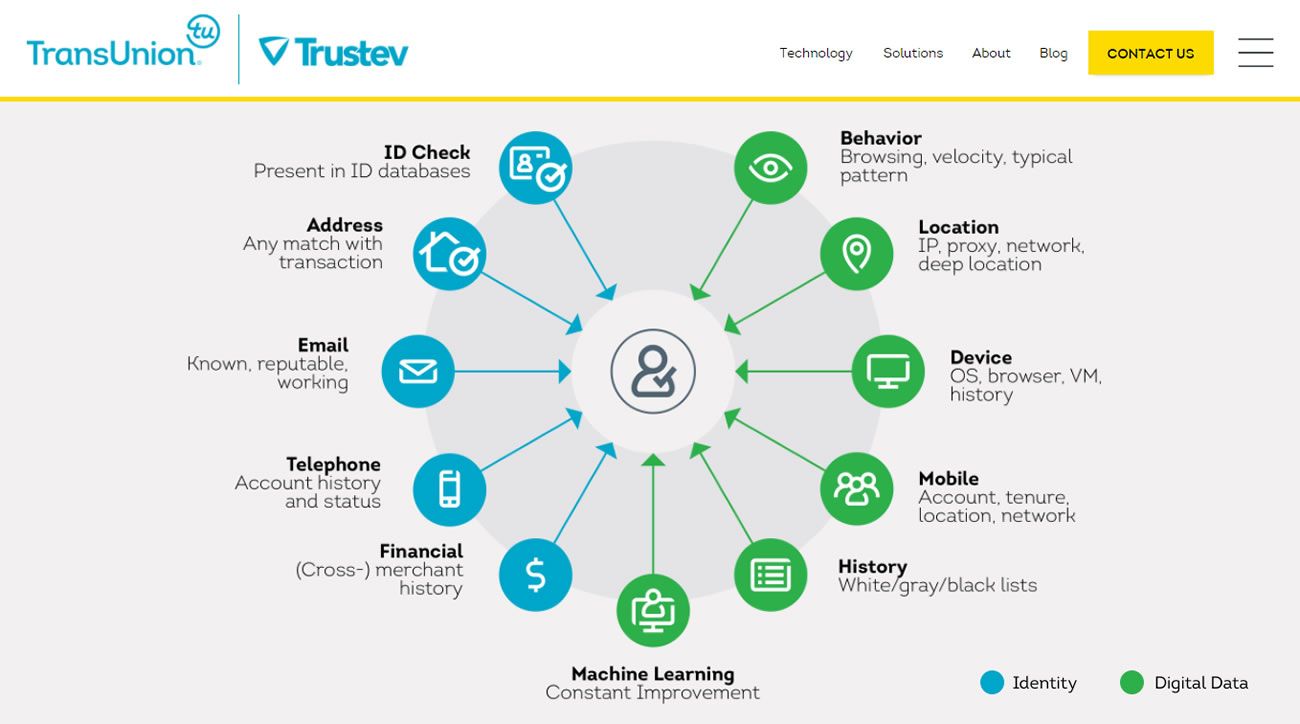

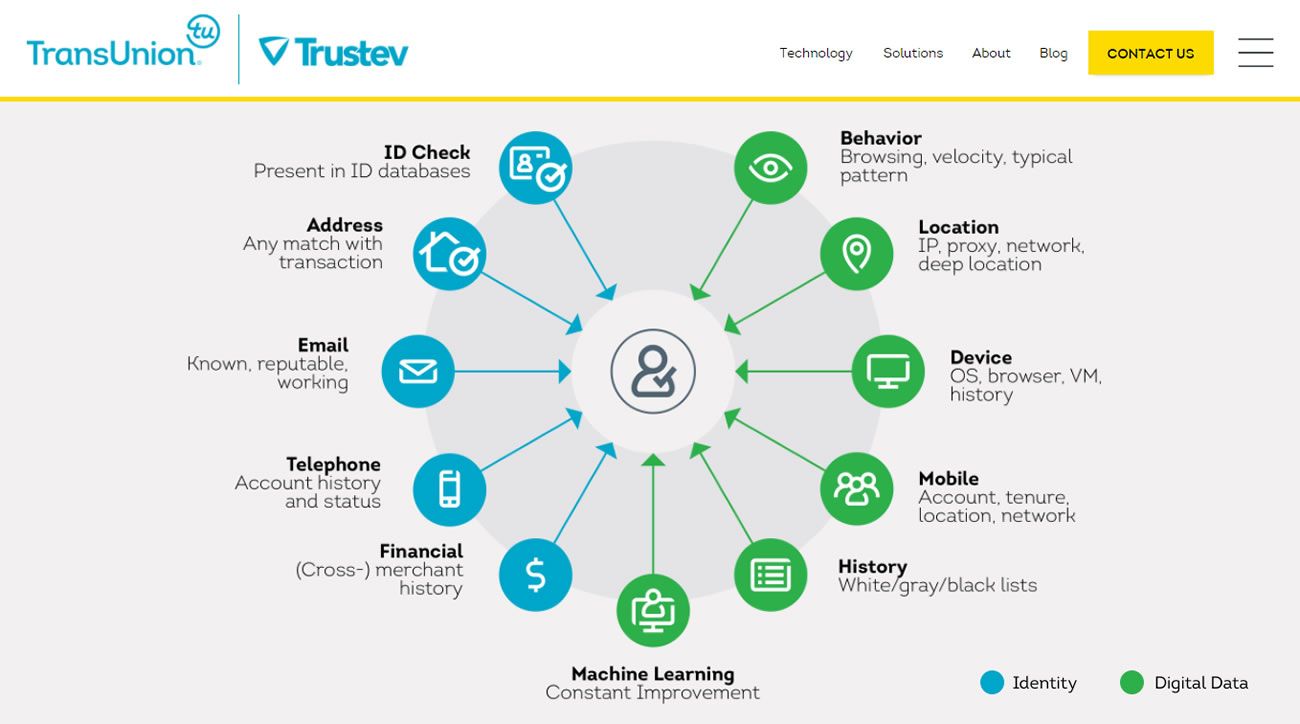

Trustev, an online fraud detection company

based in Ireland, which was acquired by the credit reporting agency TransUnion

in 2015, evaluates

online transactions for clients in financial services, government, healthcare,

and insurance, based on the analysis

of digital behaviors, identities, and devices such as phones, tablets, laptops,

game consoles, TVs, and even refrigerators. The company offers corporate

clients the ability to analyze how

visitors click and interact with websites and apps, and uses a wide range of data to assess

users, including phone numbers, email and postal addresses, browser and device

fingerprints, credit checks, transaction histories across merchants, IP

addresses, mobile carrier details and cell locations. To help “approve future

transactions” every device receives a unique

device fingerprint. Trustev also offers a social

fingerprinting technology that analyzes social media content, including “friend list analysis” and “pattern

identification”. TransUnion has integrated

Trustev technology into its own identity and fraud solutions.

Trustev uses a wide range of data to assess people, according to its website:

Screenshot of Trustev’s website, June 2, 2017 © Trustev

Similarly,

the credit reporting agency Equifax states that it has data on nearly 1

billion devices and can validate “where a device really is and whether it

is associated with other devices used in known fraud”. By combining

this data with “billions of identity and credit events to find suspicious

activity” across industries, and with information about employment and about relationships

between households, families and associates, Equifax claims to be able to

“identify devices as well as individuals”.

I am not a robot

Google’s reCaptcha product actually provides

similar functionality, at least in parts. It is embedded into millions of

websites and helps website providers decide whether a visitor is a legitimate

human being or not. Until recently, users had to solve several kinds of quick

challenges such as deciphering letters on a picture, choosing objects in a grid

of pictures, or simply clicking on an “I’m not a robot” checkbox. In 2017,

Google introduced an invisible

version of reCaptcha, explaining

that from now on “human users will be let through” without any user interaction in contrast to “suspicious ones and

bots”. The company doesn’t disclose which kinds of user data and behaviors it

uses to identify

humans. Investigations suggest

that Google doesn’t only use IP addresses, browser fingerprints, the way user’s

type, move their mouse, or use their touchscreen "before, during, and

after" a reCaptcha interaction, but also several of Google’s cookies. It is not clear whether people without

user accounts face a disadvantage, whether Google is able to identify specific

individuals rather than only “humans”, or whether Google also uses the data

recorded within reCaptcha for purposes other than for bot detection.

Digital tracking for advertising and fraud detection?

The

ubiquitous streams of behavioral data recorded for online advertising

increasingly flow into fraud detection systems. The marketing data platform Segment,

for example, offers clients easy ways to send data about their customers,

website, and mobile app users to many different marketing technology services,

but also to fraud detection companies.

One of them is Castle,

which uses “customer behavioral data to predict which users are likely a

security or fraud risk”. Another one, Smyte, helps “prevent scams,

spam, harassment and credit card fraud”.

The large

credit reporting agency Experian

offers a cross-device tracking service that provides universal

device recognition across mobile, web, and apps for digital marketing. The company promises to reconcile

and associate their client’s “existing digital identifiers”, including

“cookies, device IDs, IP addresses and more”, providing

marketers with a “ubiquitous, consistent and persistent link across all

channels”.

Experian’s

device identification technology comes from 41st parameter, an online fraud detection company that Experian acquired

in 2013. Based on 41st parameter’s technology, Experian also offers a device

intelligence solution for fraud

detection during online payments, which “establishes a reliable ID for the

device and collects rich device data”, “identifies every device on every visit

in milliseconds” and “gives unparalleled visibility into the person behind the

payment”. It is not clear whether

Experian uses the same data for its device identification services in fraud

detection and marketing.

IX. Mapping the commercial tracking and profiling landscape

In recent years, pre-existing practices of

commercial surveillance have rapidly evolved into a vast landscape of corporate

players that constantly monitor entire populations. Some actors in today’s pervasive tracking

and profiling ecosystem, such as the large platforms and other companies

with large numbers of customers, have a unique position in terms of the

scale and depth of their consumer profiles. Nevertheless, the data used to make

decisions on people in many areas of life is mostly not held in one place, but rather

assembled from several sources in real-time, as needed.

A wide range of data

and analytics companies in marketing, customer management and risk analytics

seamlessly gather, analyze, share, and trade consumer data as well as combine

it with further information from thousands of other companies. While the data

and analytics industry provides the means to deploy these powerful technologies,

businesses in many industries equally contribute both to intensifying the

amount and detail of the collected data and the ability to utilize it.

Mapping the commercial digital tracking and profiling landscape

In addition to the large online platforms and the consumer data and analytics industry, businesses in

many industries have joined today’s pervasive digital tracking and profiling ecosystems

Google and Facebook, followed by other large platforms such as Apple, Microsoft, Amazon

and Alibaba have unprecedented access to data about the lives of billions of

people. Although they have different business models and therefore play

different roles in the personal data industry, they have the power to widely dictate

the basic parameters of the overall digital markets. The large platforms mostly

restrict how other firms can directly obtain their data; in this way, they

force them to utilize the platform’s data on users within their own

ecosystems and gather additional data from beyond the platforms’ reach.

Although the large multinationals in

different sectors that have frequent interactions with hundreds of millions of

consumers are in a somewhat similar position, they not only acquire consumer

data collected by others, but often also provide data. While parts of the

financial services and telecoms sectors, as well as crucial societal areas

such as healthcare, education, and employment, are subject to stronger privacy

regulation in most jurisdictions, a wide range of companies has started to

utilize or contribute data to today’s networks of commercial surveillance.

Retailers

and other companies that sell products and services to consumers mostly also

sell data about their customers’ purchases. Media conglomerates and digital publishers

sell data about their audiences, which is then utilized by companies in most

other sectors. Telecom and broadband providers have started following

their customers through the web. Large companies in retail, media and telecom have

acquired or are acquiring data, tracking, and advertising technology firms.

With Comcast acquiring NBC Universal, and AT&T most likely acquiring Time

Warner, the large telecoms in the US are also becoming giant publishers,

creating powerful portfolios of content, data, and targeting capabilities. With

its acquisition of AOL and Yahoo, Verizon also became a “platform”.

Financial institutions have long used data on consumers for risk management, such as

credit scoring and fraud detection, as well as for marketing, customer acquisition,

and retention. They supplement their own data with external data from credit reporting

agencies, data brokers and marketing data companies. PayPal, the biggest

name in online payments, shares personal information with more than 600

third parties including other payment providers, credit reporting agencies,

identity verification and fraud detection companies, as well as with the most

advanced players within the digital tracking ecosystems. While credit card

networks and banks have shared financial data on their customers with risk data

providers for decades, they have now started selling transactional data

for marketing purposes.

A myriad of smaller and larger firms

providing websites, apps, games, and other applications are closely

connected to the marketing data ecosystem. They use services that allow them to

easily transmit data about their users to hundreds of third-party services.

Many of them sell their users’ behavioral data streams as a core part of their

business model. Even more worryingly, companies that provide new kinds of

devices such as fitness trackers also seamlessly embed

services that transfer user data to third parties.

The pervasive real-time surveillance

machine that has been developed for online advertising is rapidly

expanding into other fields including politics, pricing, credit scoring, and

risk management. Insurers all over the world have started to offer their

customers programs involving

real-time tracking of behaviors such as car driving, health activities, grocery

purchases, or visits to the fitness studio. New players in insurance

analytics and financial technology predict individual health risks based on

consumer data, as well as the creditworthiness of individuals based on

behavioral data on phone calls or web searches.

Consumer data brokers, customer management companies, and advertising agencies such as

Acxiom, Epsilon, Merkle or Wunderman/WPP play a major role in combining and

connecting data between platforms, multinationals, and the advertising

technology world. Credit reporting agencies like Experian that provide

many services in very sensitive fields such as credit reporting, identity

verification and fraud detection also play a major role in today’s pervasive

marketing data ecosystem.

Particular large companies that provide data,

analytics, and software services have been named as “platforms” as well. Oracle,

a large database and business software provider, has become a consumer data

broker in recent years. Salesforce, the market leader in customer

relationship management that is managing the customer databases of millions of

clients, yet having many customers each, has acquired

Krux, a major data company connecting and combining data all over the digital

world. The software company Adobe also plays an important role

in profiling and advertising technology.

In addition, most major companies in business

software, analytics and consulting, such as IBM, Informatica, SAS, FICO,

Accenture, Capgemini, Deloitte, and McKinsey, or even intelligence and

defense firms such as Palantir, also play a significant role in the

management and analysis of personal data, from customer relationship management

to identity management to marketing to risk analytics for insurers, banks, and

governments.

X. Towards a society of pervasive digital social control?

This report finds that the networks of

online platforms, advertising technology providers, data brokers, and other businesses

can now monitor, recognize, and analyze individuals in many life situations.

Information about individuals’ personal characteristics and behaviors is

linked, combined, and utilized across companies, databases, platforms, devices,

and services in real-time. With the actors guided only by economic goals, a data

environment has emerged in which individuals are constantly surveyed and

evaluated, categorized and grouped, rated and ranked, numbered and quantified,

included or excluded, and, as a result, treated differently.

Several key developments in recent

years have rapidly introduced unprecedented new qualities to ubiquitous

corporate surveillance. These include the rise of social media and networked

devices, the real-time tracking and linking of behavioral data streams, the

merging of online and offline data, and the consolidation of marketing and risk

management data. Pervasive digital tracking and profiling, in combination with

personalization and testing, are not only used to monitor, but also to

systematically influence people’s behavior. When companies use data

about everyday life situations to make both trivial and consequential automated

decisions about people, this may lead to discrimination, and reinforce

or even worsen existing inequalities.

In spite of its omnipresence, only the tip

of the iceberg of data and profiling activities is visible to individuals. Much

of it remains opaque and barely understood by the vast majority of people. At

the same time, people have ever fewer options to resist the power of this

data ecosystem; opting out of pervasive tracking and profiling has

essentially become synonymous with opting out of modern life. Although

corporate leaders argue that privacy

is dead (while caring

a great deal about their own privacy), Mark Andrejevic suggests that people do indeed

perceive the power asymmetries of today’s digital world, but feel “frustration

over a sense of powerlessness in the face of increasingly sophisticated and

comprehensive forms of data collection and mining”.

In light of this, this report focused on

the actual practices and inner workings of the contemporary personal data industry.

While the picture is becoming clearer, large parts of the systems in place

still remain in the dark. Enforcing transparency about corporate data practices

remains a key prerequisite to resolving the massive information asymmetries

between data companies and individuals. Hopefully this report’s findings will

encourage further work by scholars, journalists, and others in the fields of

civil rights, data protection, consumer protection, and, ideally, also of

policymakers and the companies themselves.

In 1999, Lawrence Lessig famously predicted

that left to

itself, cyberspace will become a perfect tool of control shaped primarily by

the “invisible hand” of the market. He suggested that we could “build, or

architect, or code cyberspace to protect values that we believe are

fundamental, or we can build, or architect, or code cyberspace to allow those

values to disappear”. Today, the latter has nearly been made reality by the

billions of dollars in venture capital poured into funding business models

based on the unscrupulous mass exploitation of data. The shortfall of privacy

regulation in the US and the absence of its enforcement in Europe has actively

impeded the emergence of other kinds of digital innovation, that is, of

practices, technologies, and business models that preserve freedom, democracy, social justice, and

human dignity.

On a broader level, data protection

legislation alone will not mitigate the consequences that a data-driven world

has on individuals and society, whether in the US or Europe. While consent and choice are crucial

principles to resolve some of the most urgent problems of intrusive data collection,

they can also produce an illusion

of voluntariness. Besides additional regulatory

instruments such as anti-discrimination, consumer protection, and competition

law, it will generally require a major collective effort to realize a

positive vision for a future information society. Otherwise, we might soon end

up in a society of pervasive digital social control, where privacy becomes – if

it remains at all – a luxury commodity for the rich. The building blocks are already

in place.

Further reading:

- A more comprehensive take on the issues covered

in the web publication above, as well as references and sources, can be found

in the full report, available as a PDF

download.

- The 2016 report "Networks of Control" by Wolfie Christl

and Sarah Spiekermann, which the current report is largely based on, is

available as a PDF download and as a printed book.

The production of this report, web materials, and illustrations was supported by the Open Society Foundations.