Previously on Computers Are Bad, we discussed the early history of air traffic control in the United States. The technical demands of air traffic control are well known in computer history circles because of the prominence of SAGE, but what's less well known is that SAGE itself was not an air traffic control system at all. SAGE was an air defense system, designed for the military with a specific task of ground-controlled interception (GCI). There is natural overlap between air defense and air traffic control: for example, both applications require correlating aircraft identities with radar targets. This commonality lead the Federal Aviation Agency (precursor to today's FAA) to launch a joint project with the Air Force to adapt SAGE for civilian ATC.

There are also significant differences. In general, SAGE did not provide any safety functions. It did not monitor altitude reservations for uniqueness, it did not detect loss of separation, and it did not integrate instrument procedure or terminal information. SAGE would need to gain these features to meet FAA requirements, particularly given the mid-century focus on mid-air collisions (a growing problem, with increasing air traffic, that SAGE did nothing to address).

The result was a 1959 initiative called SATIN, for SAGE Air Traffic Integration. Around the same time, the Air Force had been working on a broader enhancement program for SAGE known as the Super Combat Center (SCC). The SCC program was several different ideas grouped together: a newer transistorized computer to host SAGE, improved communications capabilities, and the relocation of Air Defense Direction Centers from conspicuous and vulnerable "SAGE Blockhouses" to hardened underground command centers, specified as an impressive 200 PSI blast overpressure resistance (for comparison, the hardened telecommunication facilities of the Cold War were mostly specified for 6 or 10 PSI).

At the program's apex, construction of the SCCs seemed so inevitable that the Air Force suspended the original SAGE project under the expectation that SCC would immediately obsolete it. For example, my own Albuquerque was one of the last Air Defense Sectors scheduled for installation of a SAGE computer. That installation was canceled; while a hardened underground center had never been in the cards for Albuquerque, the decision was made to otherwise build Albuquerque to the newer SCC design, including the transistorized computer. By the same card, the FAA's interest in a civilian ATC capability, and thus the SATIN project, came to be grouped together with the SCC program as just another component of SAGE's next phase of development.

SAGE had originally been engineered by MIT's Lincoln Laboratory, then the national center of expertise in all things radar. By the late 1950s a large portion of the Lincoln Laboratory staff were working on air defense systems and specifically SAGE. Those projects had become so large that MIT opted to split them off into a new organization, which through some obscure means came to be called the MITRE Corporation. MITRE was to be a general military R&D and consulting contractor, but in its early years it was essentially the SAGE company.

The FAA contracted MITRE to deliver the SATIN project, and MITRE subcontracted software to the Systems Development Corporation, originally part of RAND and among the ancestors of today's L3Harris. For the hardware, MITRE had long used IBM, who designed and built the original AN/FSQ-7 SAGE computer and its putative transistorized replacement, the AN/FSQ-32. MITRE began a series of engineering studies, and then an evaluation program on prototype SATIN technology.

There is a somewhat tenuous claim that you will oft see repeated, that the AN/FSQ-7 is the largest computer ever built. It did occupy the vast majority of the floorspace of the four-story buildings built around it. The power consumption was around 3 MW, and the heat load required an air conditioning system at the very frontier of HVAC engineering (you can imagine that nearly all of that 3 MW had to be blown out of the building on a continuing basis). One of the major goals of the AN/FSQ-32 was reduced size and power consumption, with the lower heat load in particular being a critical requirement for installation deep underground. Of course, the "deep underground" part more than wiped out any savings from the improved technology.

From Air Defense to Air Traffic Control

By the late 1950s, enormous spending for the rapid built-out of defense systems including SAGE and the air defense radar system (then the Permanent System) had fatigued the national budget and Congress. The winds of the Cold War had once again changed. In 1959, MITRE had begun operation of a prototype civilian SAGE capability called CHARM, the CAA High Altitude Remote Monitor (CAA had become the FAA during the course of the CHARM effort). CHARM used MIT's Whirlwind computer to process high-altitude radar data from the Boston ARTCC (Air Route Traffic Control Center), which it displayed to operators while continuously evaluating aircraft movements for possible conflicts. CHARM was designed for interoperability with SAGE, the ultimate goal being the addition of the CHARM software package to existing SAGE computers. None of that would ever happen; by the time the ball dropped for the year 1960 the Super Combat Center program had been almost completely canceled. SATIN, and the whole idea of civilian air traffic control with SAGE, became blast damage.

In 1961, the Beacon Report concluded that there was an immediate need for a centralized, automated air traffic control system. Mid-air collisions had become a significant political issue, subject of congressional hearings and GAO reports. The FAA seemed to be failing to rise to the task of safe civilian ATC, a perilous situation for such a new agency... and after the cancellation of the SCCs, the FAA's entire plan for computerized ATC was gone.

During the late 1950s and 1960s, the FAA adopted computer systems in a piecemeal fashion. Many enroute control centers (ARTCCs), and even some terminal facilities, had some type of computer system installed. These were often custom software running on commodity computers, limited to tasks like recording flight plans and making them available to controllers at other terminals. Correlation of radar targets with flight plans was generally manual, as were safety functions like conflict detection.

These systems were limited in scale—the biggest problem being that some ARTCCs remained completely manual even in the late 1960s. On the upside, they demonstrated much of the technology required, and provided a test bed for implementation. Many of the individual technical components of ATC were under development, particularly within IBM and Raytheon, but there was no coordinated nationwide program. This situation resulted in part from a very intentional decision by the FAA to grant more decision making power to its regional offices, a concept that was successful in some areas but in retrospect disastrous in others. In 1967, the Department of Transportation was formed as a new cabinet-level executive department. The FAA, then the Federal Aviation Agency, was reorganized into DOT and renamed the Federal Aviation Administration. The new Administration had a clear imperative from both the President and Congress: figure out air traffic control.

In the late 1960s, the FAA coined a new term: the National Airspace System 1, a fully standardized, nationwide system of procedures and systems that would safely coordinate air traffic into the indefinite future. Automation of the NAS began with NAS Enroute Stage A, which would automate the ARTCCs that handled high-altitude aircraft on their way between terminals. The remit was more or less "just like SAGE but with the SATIN features," and when it came to contracting, the FAA decided to cut the middlemen and go directly to the hardware manufacturer: IBM.

The IBM 9020

It was 1967 by the time NAS Enroute Stage A was underway, nearly 20 years since SAGE development had begun. IBM would thus benefit from considerable advancements in computer technology in general. Chief among them was the 1965 introduction of the System/360. S/360 was a milestone in the development of the computer: a family of solid-state, microcoded computers with a common architecture for software and peripheral interconnection. S/360's chief designer, Gene Amdahl, was a genius of computer architecture who developed a particular interest in parallel and multiprocessing systems. Soon after the S/360 project, he left IBM to start the Amdahl Corporation, briefly one of IBM's chief competitors. During his short 1960s tenure at IBM, though, Amdahl contributed IBM's concept of the "multisystem."

A multisystem consisted of multiple independent computers that operated together as a single system. There is quite a bit of conceptual similarity between the multisystem and modern concepts like multiprocessing and distributed computing, but remember that this was the 1960s, and engineers were probing out the possibilities of computer-to-computer communication for the first time. Some of the ideas of S/360 multisystems read as strikingly modern and prescient of techniques used today (like atomic resource locking for peripherals and shared memory), while others are more clearly of their time (the general fact that S/360 multisystems tended to assign their CPUs exclusively to a specific task).

One of the great animating tensions of 1960s computer history is the ever-moving front between batch processing systems and realtime computing systems. IBM had its heritage manufacturing unit record data processing machines, in which a physical stack of punched cards was the unit of work, and input and output ultimately occurred between humans on two sides of a service window. IBM computers were designed around the same model: a "job" was entered into the machine, stored until it reached the end of the queue, processed, and then the output was stored for later retrieval. One could argue that all computers still work this way, it's just process scheduling, but IBM had originally envisioned job queuing times measured in hours rather than milliseconds.

The batch model of computing was fighting a battle on multiple fronts: rising popularity of time-sharing systems meant servicing multiple terminals simultaneously and, ideally, completing simple jobs interactively while the user waited. Remote terminals allowed clerks to enter and retrieve data right where business transactions were taking place, and customers standing at ticket counters expected prompt service. Perhaps most difficult of all, fast-moving airplanes and even faster-moving missiles required sub-second decisions by computers in defense applications.

IBM approached the FAA's NAS Enroute Stage A contract as one that required a real-time system (to meet the short timelines necessary in air traffic control) and a multisystem (to meet the FAA's exceptionally high uptime and performance requirements). They also intended to build the NAS automation on an existing, commodity architecture to the greatest extent possible. The result was the IBM 9020.

The 9020 is a fascinating system, exemplary of so many of the challenges and excitement of the birth of the modern computer. On the one hand, a 9020 is a sophisticated, fault-tolerant, high-performance computer system with impressive diagnostic capabilities and remarkably dynamic resource allocation. On the other hand, a 9020 is just six to seven S/360 computers married to each other with a vibe that is more duct tape and bailing wire than aerospace aluminum and titanium.

The first full-scale 9020 was installed in Jacksonville, Florida, late in 1967. Along with prototype systems at the FAA's experimental center and at Raytheon (due to the 9020's close interaction with Raytheon-built radar systems), the early 9020 computers served as development and test platforms for a complex and completely new software system written mostly in JOVIAL. JOVIAL isn't a particularly well-remembered programming language, based on ALGOL with modifications to better suit real-time computer systems. The Air Force was investing extensively in real-time computing capabilities for air defense and JOVIAL was, for practical purposes, an Air Force language.

It's not completely clear to me why IBM selected JOVIAL for enroute stage A, but we can make an informed guess. There were very few high-level programming languages that were suitable for real-time use at all in the 1960s, and JOVIAL had been created by Systems Development Corporation (the original SAGE software vendor) and widely used for both avionics and air defense. The SCC project, if it had been completed, would likely have involved rewriting large parts of SAGE in JOVIAL. For that reason, JOVIAL had been used for some of the FAA's earlier ATC projects including SATIN. At the end of the day, JOVIAL was probably an irritating (due to its external origin) but obvious choice for IBM.

More interesting than the programming language is the architecture of the 9020. It is, fortunately, well described in various papers and a special issue of IBM Systems Journal. I will simplify IBM's description of the architecture to be more legible to a modern reader who hasn't worked for IBM for a decade.

Picture this: seven IBM S/360 computers, of various models, are connected to a common address and memory bus used for interaction with storage. These computers are referred to as Compute Elements and I/O Control Elements, forming two pools of machines dedicated to two different sets of tasks. Also on that bus are something like 10 Storage Elements, specialized machines that function like memory controllers with additional features for locking, prioritization, and diagnostics. These Storage Elements provide either 131 kB or about 1 MB of memory each; due to various limitations the maximum possible memory capacity of a 9020 is about 3.4 MB, not all of which is usable at any given time due to redundancy.

At least three Compute Elements, and up to four, serve as the general-purpose part of the system where the main application software is executed. Three I/O Control Elements existed mostly as "smart" controllers for peripherals connected to their channels, the IBM parlance for what we might now call an expansion bus.

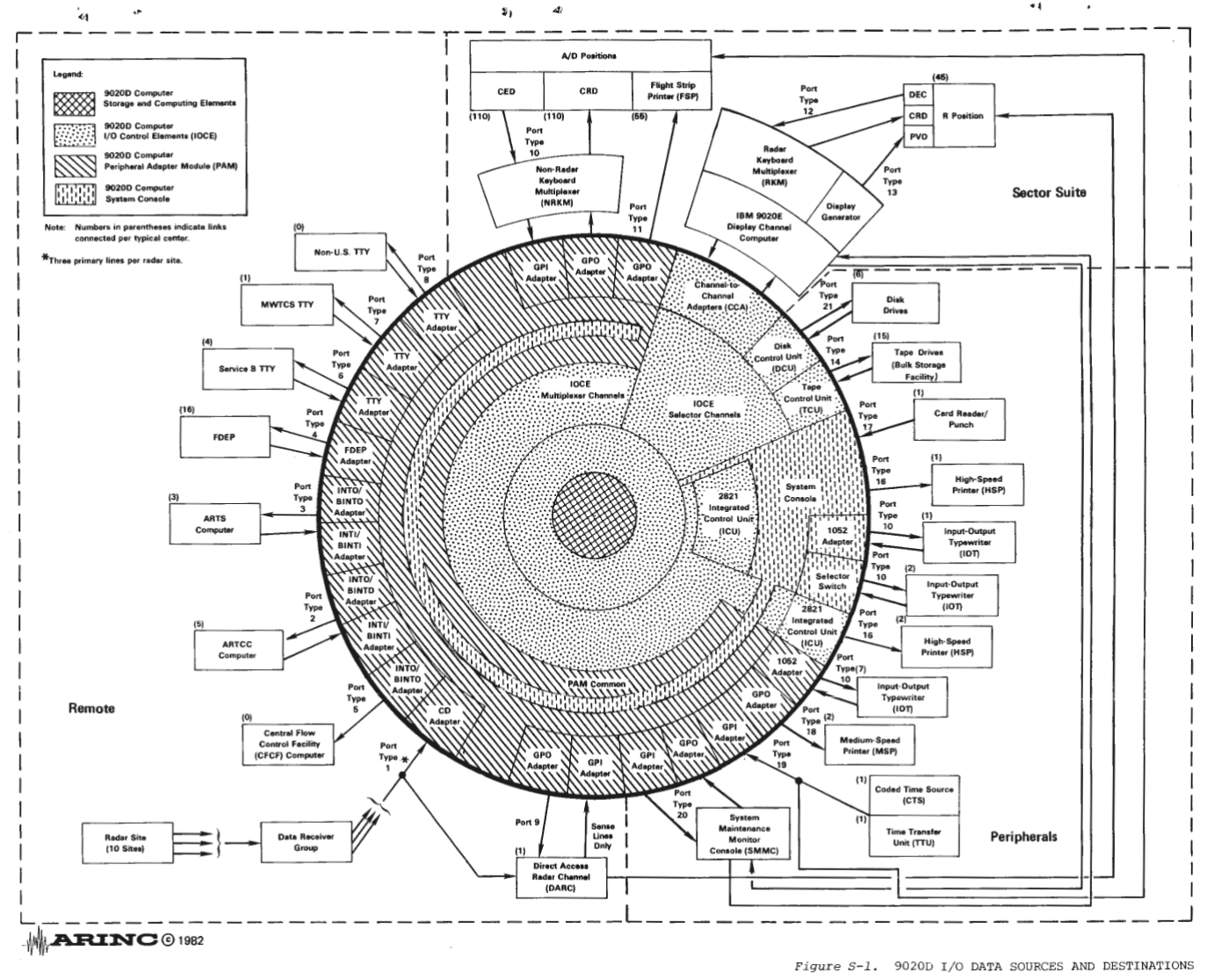

The 9020 received input from a huge number of sources (radar digitizers, teletypes at airlines and flight service stations, controller workstations, other ARTCCs). Similarly, it sent output to most of these endpoints as well. All of these communications channels, with perhaps the exception of the direct 9020-to-9020 links between ARTCCs, were very slow even by the standards of the time. The I/O Control Elements each used two of their high-speed channels for interconnection with display controllers (discussed later) and tape drives in the ARTCC, while the third high-speed channel connected to a multiplexing system called the Peripheral Adapter Module that connected the computer to dozens of peripherals in the ARTCC and leased telephone lines to radar stations, offices, and other ATC sites.

Any given I/O Control Element had a full-time job of passing data between peripherals and storage elements, with steps to validate and preprocess data. In addition to ATC-specific I/O devices, the Control Elements also used their Peripheral Adapter Modules to communicate with the System Console. The System Console is one of the most unique properties of the 9020, and one of the achievements of which IBM seems most proud.

Multisystem installations of S/360s were not necessarily new, but the 9020 was one of the first attempts to present a cluster of S/360s as a single unified machine. The System Console manifested that goal. It was, on first glance, not that different from the operator's consoles found on each of the individual S/360 machines. It was much more than that, though: it was the operator's console for all seven of them. During normal 9020 operation, a single operator at the system console could supervise all components of the system through alarms and monitors, interact with any element of the system via a teletypewriter terminal, and even manually interact with the shared storage bus for troubleshooting and setup. The significance of the System Console's central control was such that the individual S/360 machines, when operating as part of the Multisystem, disabled their local operator's consoles entirely.

One of the practical purposes of the System Console was to manage partitioning of the system. A typical 9020 had three compute elements and three I/O control elements, an especially large system could have a fourth compute element for added capacity. The system was sized to produce 50% redundancy during peak traffic. In other words, a 9020 could run the full normal ATC workload on just two of the compute elements and two of the I/O control elements. The remaining elements could be left in a "standby" state in which the multisystem would automatically bring them online if one of the in-service elements failed, and this redundancy mechanism was critical to meeting the FAA's reliability requirement. You could also use the out-of-service elements for other workloads, though.

For example, you could remove one of the S/360s from the multisystem and then operate it manually or run "offline" software. An S/360 operating this way is described as "S/360 compatibility mode" in IBM documentation, since it reduces the individual compute element to a normal standalone computer. IBM developed an extensive library of diagnostic tools that could be run on elements in standby mode, many of which were only slight modifications of standard S/360 tools. You could also use the offline machines in more interesting ways, by bringing up a complete ATC software chain running on a smaller number of elements. For training new controllers, for example, one compute element and one I/O control element could be removed from the multisystem and used to form a separate partition of the machine that operated on recorded training data. This partition could have its own assigned peripherals and storage area and largely operate as if it were a complete second 9020.

Multisystem Architecture

You probably have some questions about how IBM achieved these multisystem capabilities, given the immature state of operating systems design at the time. The 9020 used an operating system derived from OS/360 MVT, an advanced form of OS/360 with a multitasking capability that was state-of-the-art in the mid-1960s but nonetheless very limited and with many practical problems. Fortunately, IBM was not exactly building a general-purpose machine, but a dedicated system with one function. This allowed the software to be relatively simple.

The core of the 9020 software system is called the control program, which is similar to what we would call a scheduler today. During routine operation of the 9020, any of the individual computers might begin execution of the control program at any time—typically either because the computer's previous task was complete (along the lines of cooperative multitasking) or because an interrupt had been received (along the lines of preemptive multitasking). To meet performance and timing requirements, especially with the large number of peripherals involved, the 9020 extensively used interrupts which could either be generated and handled within a specific machine or sent across the entire multisystem bus.

The control program's main function is to choose the next task to execute. Since it can be started on any machine at any time, it must be reentrant. The fact that all of the machines have shared memory simplifies the control program's task, since it has direct access to all of the running programs. Shared memory also added the complexity that the control program has to implement locking and conflict detection to ensure that it doesn't start the same task on multiple machines at once, or start multiple tasks that will require interaction with the same peripheral.

You might wonder about how, exactly, the shared memory was implemented. The storage elements were not complete computers, but did implement features to prevent conflicts between simultaneous access by two machines, for example. By necessity, all of the memory management used for the multisystem is quite simple. Access conflicts were resolved by choosing one machine and making the other wait until the next bus cycle. Each machine had a "private" storage area, called the preferential storage area. A register on each element contained an offset added to all memory addresses that ensured the preferential storage areas did not overlap. Beyond that, all memory had to be acquired by calling system subroutines provided by the control program, so that the control program could manage memory regions. Several different types of memory allocations were available for different purposes, ranging from arbitrary blocks for internal use by programs to shared buffer areas that multiple machines could use to queue data for an I/O Control Element to send elsewhere.

At any time during execution of normal programs, an interrupt could be generated indicating a problem with the system (IBM gives the examples of a detection of high temperature or loss of A/C power in one of the compute elements). Whenever the control program began execution, it would potentially detect other error conditions using its more advanced understanding of the state of tasks. For example, the control program might detect that a program has exited abnormally, or that allocation of memory has failed, or an I/O operation has timed out without completing. All of these situations constitute operational errors, and result in the Control Program ceding execution to the Operational Error Analysis Program or OEAP.

The OEAP is where error-handling logic lives, but also a surprising portion of the overall control of the multisystem. The OEAP begins by performing self-diagnosis. Whatever started the OEAP, whether the control program or a hardware interrupt, is expected to leave some minimal data on the nature of the failure in a register. The OEAP reads that register and then follows an automated data-collection procedure that could involve reading other registers on the local machine, requesting registers from other machines, and requesting memory contents from storage elements. Based on the diagnosis, the OEAP has different options: some errors are often transient (like communications problems), so the OEAP might do nothing and simply allow the control program to start the task again.

On the other hand, some errors could indicate a serious problem with a component of the system, like a storage element that is no longer responding to read and write operations in its address range. In those more critical cases, the OEAP will rewrite configuration registers on the various elements of the system and then reset them—and on initialization, the configuration registers will cause them to assume new states in terms of membership in the multisystem. In this way, the OEAP is capable of recovering from "solid" hardware failures by simply reconfiguring the system to no longer use the failed hardware. Most of the time, that involves changing the failed element's configuration from "online" to "offline," and choosing an element in "online standby" and changing its configuration to "online." During the next execution of the control program, it will start tasks on the newly "online" element, and the newly "offline" element may as well have never existed.

The details are, of course, a little more complex. In the case of a failed storage element, for example, there's a problem of memory addresses. The 9020 multisystem doesn't have virtual memory in the modern sense, addresses are more or less absolute (ignoring some logical addressing available for specific types of memory allocations). That means that if a storage element fails, any machines which have been using memory addresses within that element will need to have a set of registers for memory address offsets reconfigured and then execution reset. Basically, by changing offsets, the OEAP can "remap" the memory in use by a compute or I/O control element to a different storage element. Redundancy is also built in to the software design to make these operations less critical. For example, some important parts of memory are stored in duplicate with an offset between the two copies large enough to ensure that they will never fall on the same physical storage element.

So far we have only really talked about the "operational error" part, though, and not the "analysis." In the proud tradition of IBM, the 9020 was designed from the ground up for diagnosis. A considerable part of IBM's discussion of the architecture of the Control Program, for example, is devoted to its "timing analysis" feature. That capability allows the Control Program to commit to tape a record of when each task began execution, on which element, and how long it took. The output is a set of start and duration times, with task metadata, remarkably similar to what we would now call a "span" in distributed tracing. Engineers used these records to analyze the performance of the system and more accurately determine load limits such as the number of in-air flights that could be simultaneously tracked. Of course, details of the time analysis system remind us that computers of this era were very slow: the resolution on task-start timestamps was only 1/2 second, although durations were recorded at the relatively exact 1/60th of a second.

That was just the control program, though, and the system's limited ability to write timing analysis data (which, even on the slow computers, tended to be produced faster than the tape drives could write it and so had to fit within a buffer memory area for practical purposes) meant that it was only enabled as needed. The OEAP provided long-term analysis of the performance of the entire machine. Whenever the OEAP was invoked, even if it determined that a problem was transient or "soft" and took no action, it would write statistical records of the nature of the error and the involved elements. When the OEAP detected an unusually large number of soft errors from the same physical equipment, it would automatically reconfigure the system to remove that equipment from service and then generate an alarm.

Alerts generated by the OEAP were recorded by a printer connected to the System Console, and indicated by lights on the System Console. A few controls on the System Console allowed the operator manual intervention when needed, for example to force a reconfiguration.

One of the interesting aspects of the OEAP is where it runs. The 9020 multisystem is truly a distributed one in that there is no "leader." The control program, as we have discussed, simply starts on whichever machine is looking for work. In practice, it may sometimes run simultaneously on multiple machines, which is acceptable as it implements precautions to prevent stepping on its own toes.

This model is a little more complex for the OEAP, because of the fact that it deals specifically with failures. Consider a specific failure scenario: loss of power. IBM equipped each of the functional components of the 9020 with a battery backup, but they only rate the battery backup for 5.5 seconds of operation. That isn't long enough for a generator to reliably pick up the load, so this isn't a UPS as we would use today. It's more of a dying gasp system: the computer can "know" that it has lost power and continue to operate long enough stabilize the state of the system for faster resumption.

When a compute element or I/O control element loses power, an interrupt is generated within that single machine that starts the OEAP. The OEAP performs a series of actions, which include generating an interrupt across the entire system to trigger reconfiguration (it is possible, even likely given the physical installations, that the power loss is isolated to the single machine) and resetting task states in the control program so that the machine's tasks can be restarted elsewhere. The OEAP also informs the system console and writes out records of what has happened. Ideally, this all completes in 5.5 seconds while battery power remains reliable.

In the real world, there could be problems that lead to slow OEAP execution, or the batteries could fail to make it for long enough, or for that matter the compute element could encounter some kind of fundamentally different problem. The fact that the OEAP is executing on a machine means that something has gone wrong, and so until the OEAP completes analysis, the machine that it is running on should be considered suspect. The 9020 resolves this contradiction through teamwork: beginning of OEAP execution on any machine in the total system generates an interrupt that starts the OEAP on other machines in a "time-down" mode. The "time-down" OEAPs wait for a random time interval and then check the shared memory to see if the original OEAP has marked its execution as completed. If not, the first OEAP to complete its time-down timer will take over OEAP execution and attempt to complete diagnostics from afar. That process can, potentially, repeat multiple times: in some scenario where two of the three compute elements have failed, the remaining third element will eventually give up on waiting for the first two and run the OEAP itself. In theory, someone will eventually diagnose every problem. IBM asserts that system recovery should always complete within 30 seconds.

Let's work a couple of practical examples, to edify our understanding of the Control Program and OEAP. Say that a program running on a Compute Element sets up a write operation for an I/O Control Element, which formats and sends the data to a Peripheral Adapter Module which attempts to send it to an offsite peripheral (say an air traffic control tower teleprinter) but fails. A timer that tracks the I/O operation will eventually fail, triggering the OEAP on the I/O control element running the task. The OEAP reads out the error register on its new home, discovers that it is an I/O problem related to a PAM, and then speaks over the channel to request the value of state registers from the PAM. These registers contain flags for various possible states of peripheral connections, and from these the OEAP can determine that sending a message has failed because there was no response. These types of errors are often transient, due to telephone network trouble or bad luck, so the OEAP increments counters for future reference, looks up the application task that tried to send the message and changes its state to incomplete, clears registers on the PAM and I/O control element, and then hands execution back to the Control Program. The Control Program will most likely attempt to do the exact same thing over again, but in the case of a transient error, it'll probably work this time.

Consider a more severe case, where the Control Program starts a task on a Compute Element that simply never finishes. A timer runs down to detect this condition, and an interrupt at the end of the timer starts the Control Program, which checks the state and discovers the still-unfinished task. Throwing its hands in the air, the Control Program sets some flags in the error register and hands execution to the OEAP. The OEAP starts on the same machine, but also interrupts other machines to start the OEAP in time-down mode in case the machine is too broken to complete error handling. It then reads the error register and examines other registers and storage contents. Determining that some indeterminate problem has occurred with the Compute Element, the OEAP triggers what IBM confusingly calls a "logout" but we might today call a "core dump" (ironically an old term that was more appropriate in this era). The "logout" entails copying the contents of all of the registers and counters to the preferential storage area and then directing, via channel, one of the tape drives to write it all to a tape kept ready for this purpose—the syslog of its day. Once that's complete, the OEAP will reset the Compute Element and hand back to the Control Program to try again... unless counters indicate that this same thing has happened recently. In that case, the OEAP will update the configuration register on the running machine to change its status to offline, and choose a machine in online-standby. It will write to that machine's register, changing its status to online. A final interrupt causes the Control Program to start on both machines, taking them into their new states.

Lengthy FAA procedure manuals described what would happen next. These are unfortunately difficult to obtain, but from IBM documentation we know that basic information on errors was printed for the system operator. The system operator would likely then use the system console to place the suspicious element in "test" mode, which completely isolates it to behave more or less like a normal S/360. At that point, the operator could use one of the tape drives attached to the problem machine to load IBM's diagnostic library and perform offline troubleshooting. The way the tape drives are hooked up to specific machines is important; in fact, since the OEAP is fairly large, it is only stored in one copy on one Storage Element. The 9020 requires that one of the tape drives always have a "system tape" ready with the OEAP itself, and low-level logic in the elements allows the OEAP to be read from the ready-to-go system tape in case the storage element that contains it fails to respond.

A final interesting note about the OEAP is a clever optimization called "problem program mode." During analysis and handling of an error, the OEAP can decide that the critical phase of error handling has ended and the situation is no longer time sensitive. For example, the OEAP might decide that no action is required except for updating statistics, which can comfortably happen with a slight delay. These lower-priority remaining tasks can be added to memory as "normal" application tasks, to be run by the Control Program like any other task after error handling is complete. Think of it as a deferral mechanism, to avoid the OEAP locking up a machine for any longer than necessary.

For the sake of clarity, I'll note again an interesting fact by quoting IBM directly: "OEAP has sole responsibility for maintaining the system configuration." The configuration model of the 9020 system is a little unintuitive to me. Each machine has its own configuration register that tells it what its task is and whether it is online or offline (or one of several states in between like online-standby). The OEAP reconfigures the system by running on any one machine and writing the configuration registers of both the machine it's running on, and all of the other machines via the shared bus. Most reconfigurations happen because the OEAP has detected a problem and is working around it, but if the operator manually reconfigures the system (for example to facilitate testing or training), they also do so by triggering an interrupt that leads the Control Program to start the OEAP. The System Console has buttons for this, along with toggles to set up a sort of "main configuration register" that determines how the OEAP will try to set up the system.

The Air Traffic Control Application

This has become a fairly long article by my norms, and I haven't even really talked about air traffic control that much. Well, here it comes: the application that actually ran on the 9020, which seems to have had no particular name, besides perhaps Central Computing Complex (although this seems to have been adopted mostly to differentiate it from the Display Complex, discussed soon).

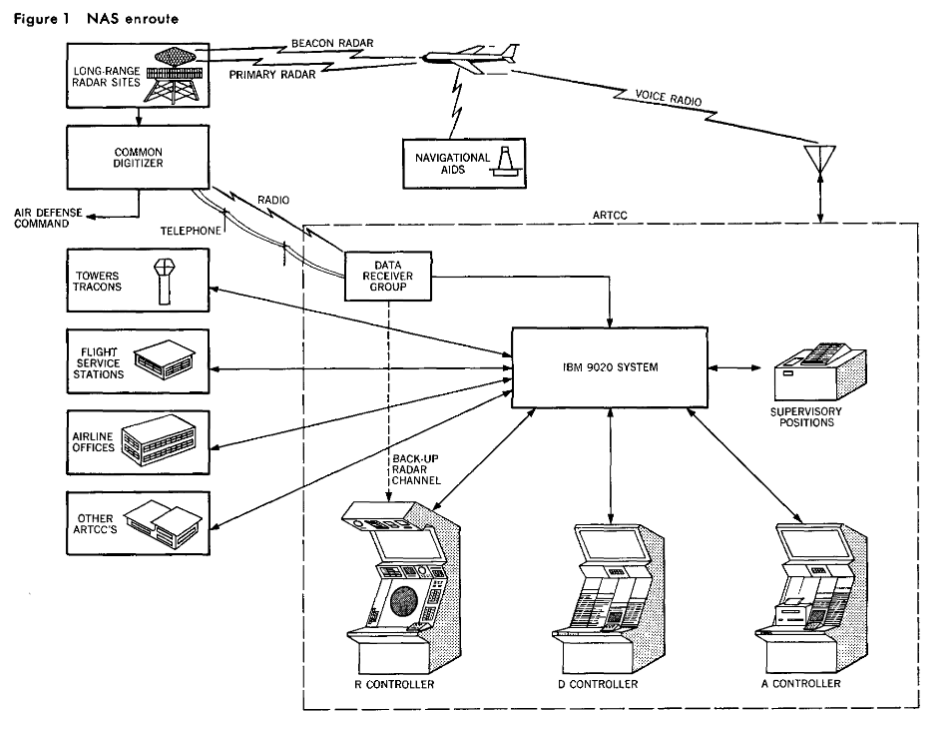

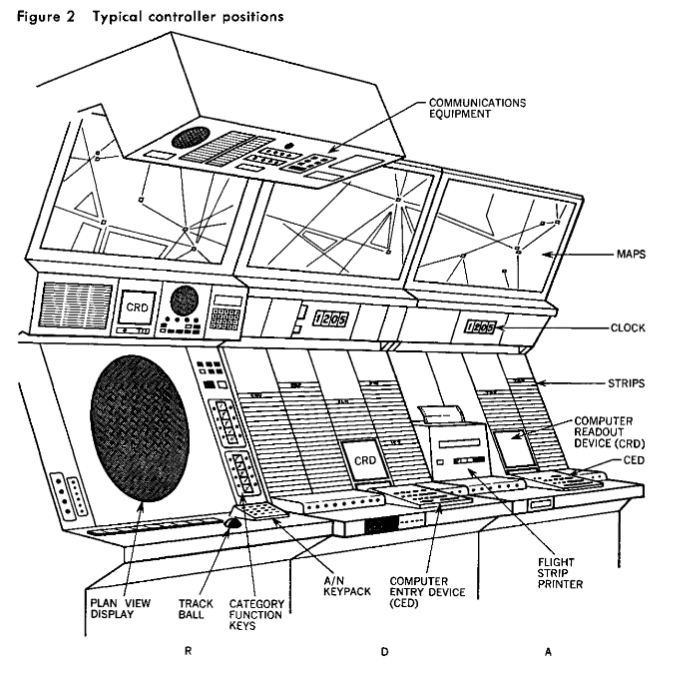

First, let's talk about the hardware landscape of the ARTCC and the 9020's role. An ARTCC handles a number of sectors, say around 30. Under the 9020 system, each of these sectors has three controllers associated with it, called the R, D, and A controllers. The R controller is responsible for monitoring and interpreting the radar, the D controller for managing flight plans and flight strips, and the A controller is something of a generalist who assists the other two. The three people sit at something like a long desk, made up of the R, D, and A consoles side by side.

The R console is the most recognizable to modern eyes, as its centerpiece is a 22" CRT plan-view radar display. The plan-view display (PVD) of the 9020 system is significantly more sophisticated than the SAGE PVD on which it is modeled. Most notably, the 9020 PVD is capable of displaying text and icons. No longer does a controller use a light gun to select a target for a teleprinter to identify; the "data blocks" giving basic information on a flight were actually shown on the PVD next to the radar contact. A trackball and a set of buttons even allowed the controller to select targets to query for more information or update flight data. This was quite a feat of technology even in 1970, and in fact one that the 9020 was not capable of. Well, it was actually capable of it, but not initially.

The original NAS stage A architecture separated the air traffic control data function and radar display function into two completely separate systems. The former was contracted to IBM, the latter to Raytheon, due to their significant experience building similar systems for the military. Early IBM 9020 installations sat alongside a Raytheon 730 Display Channel, a very specialized system that was nearly as large as the 9020. The Display Channel's role was to receive radar contact data and flight information in digital form from the 9020, and convert it into drawing instructions sent over a high-speed serial connection to each individual PVD. A single Display Channel was responsible for up to 60 PVDs. Further complicating things, sector workstations were reconfigurable to handle changing workloads. The same sector might be displayed on multiple PVDs, and where sectors met, PVDs often overlapped so the same contact would be visible to controllers for both sectors. The Display Channel had a fairly complex task to get the right radar contacts and data blocks to the right displays, and in the right places.

Later on, the FAA opted to contract IBM to build a slightly more sophisticated version of the Display Channel that supported additional PVDs and provided better uptime. To meet that contract, IBM used another 9020. Some ARTCCs thus had two complete 9020 systems, called the Central Computer Complex (CCC) and the Display Channel Complex (DCC).

The PVD is the most conspicuous part of the controller console, but there's a lot of other equipment there, and the rest of it is directly connected to the 9020 (CCC). At the R controller's position, a set of "hotkeys" allow for quickly entering flight data (like new altitudes) and a computer readout device (CRD), a CRT that displays 25x20 text for general output. For example, when a controller selects a target on the PVD to query for details, that query is sent to the 9020 CCC which shows the result on the R controller's CRD above the PVD.

At the D controller's position, right next door, a large rack of slots for flight strips (small paper strips used to logically organize flight clearances, still in use today in some contexts) surrounds the D controller's CRD. The D controller also has a Computer Entry Device, or CED, a specialized keyboard that allows the D controller to retrieve and update flight plans and clearances based on requests from pilots or changes in the airspace situation. To their right, a modified teleprinter is dedicated to producing the flight strips that they arrange in front of them. Flight strips are automatically printed when an aircraft enters the sector, or when the controller enters changes. The A controller's position to the right of the flight strip printer is largely the same as the D controller's position, with another CRD and CED that operate independently from the D controller's—valuable during peak traffic.

While controller consoles are the most visible peripherals of the system, they're far from the only ones. Each 9020 system had an extensive set of teletypewriter circuits. Some of these were local; for example, the ATC supervisor had a dedicated TTY where they could not only interact with flight data (to assist a sector controller for example) but also interact with the status of the NAS automation itself (for example to query the status of a malfunctioning radar site and then remove it from use for PVDs).

Since the 9020 was also the locus of flight planning, TTYs were provided in air traffic control towers, terminal radar facilities, and even the dispatch offices of airlines. These allowed flight plans to be entered into the 9020 before the aircraft was handed off to enroute control. Flight service stations functioned more or less as the dispatch offices for general aviation, so they were similarly equipped with TTYs for flight plan management. In many areas, military controllers at air defense sectors were also provided with TTYs for convenient access to flight plans. Not least of all, each 9020 had high-speed leased lines to its neighboring 9020s. Flights passing from one ARTCC to the next had their flight strip "digitally passed" by transmission from one 9020 to the next.

A set of high-speed line printers connected to the 9020 printed diagnostic data as well as summary and audit reports on air traffic. Similar audit data, including a detailed record of clearances, was written to tape drives for future reference.

To organize the whole operation, IBM divided the software architecture of the system into the "supervisor state" and the "problem state." These are reasonably analogous to kernel and user space today, and "problem" is meant as in "the problem the computer solves" rather than "a problem has occurred." The Control Program and OEAP run in the supervisor state, everything else runs after the Control Program has set up a machine in the Problem State and started a given program.

IBM organized the application software into five modules, which they called the five Programs. These are Input Processing, Flight Processing, Radar Processing, Output Processing, and Liaison Management. Most of these are fairly self-explanatory, but the list reveals the remarkably asynchronous design of the system. Consider an example, we'll say a general aviation flight taking off from an airport inside of one of the ARTCC's sectors.

The pilot first contacts a Flight Service Station, which uses their TTY to enter a flight plan into the 9020. Next, the pilot interacts with the control tower, which in the process of giving a takeoff clearance uses their TTY to inform the 9020 that the flight plan is active. They may also update the flight plan with the aircraft's planned movements shortly after takeoff, if they have changed due to operating conditions. The Input Processing program handles all of these TTY inputs, parsing them into records stored on a Storage Element. In case any errors occur, like an invalid entry, those are also written to the Storage Element, where the Output Processing program picks them up and sends an appropriate message to the originating TTY. IBM notes that there were, as originally designed, about 100 types of input messages parsed by the input processing program.

As the aircraft takes off, it is detected by a radar site (such as a Permanent System radar or Air Route Surveillance Radar) which digitally encodes the radar contact (a Raytheon system) for transmission to the 9020. The Radar Processing program receives these messages, converts radial radar coordinates to the XY plane used by the system, correlates contacts with similar XY positions from multiple radar sites into a single logical contact, and computes each contact's apparent heading and speed to extrapolate future positions. Complicating things, the 9020 went into service during the development of secondary surveillance radar, also known as the transponder system 2. On appropriately equipped aircraft, the transponder provides altitude. The Radar Processing system makes an altitude determination on each aircraft, a slightly more complicated task than you might expect as, at the time, only some radar systems and some transponders provided altitude information. The Radar Processing program thus had to track if it had altitude information at all and, if so, where from. In the mean time, the Radar Processing program tracked the state of the radar sites and reported any apparent trouble (such as loss of data or abnormal data) to the supervisor.

I put a lot of time into writing this, and I hope that you enjoy reading it. If you can spare a few dollars, consider supporting me on ko-fi. You'll receive an occasional extra, subscribers-only post, and defray the costs of providing artisanal, hand-built world wide web directly from Albuquerque, New Mexico.

The Flight Processing program periodically evaluates all targets from the Radar Processing program against all filed flight plans, correlating radar targets with filed flight plans, calculating navigational deviations, and predicting future paths. Among other outputs, the Flight Processing program generated up-to-date flight strips for each aircraft and predicted their arrival times at each flight plan fix for controller's planning purposes. The Flight Processing program hosted a set of rules used for safety protections, such as separation distances. This capability was fairly minimal during the 9020's original development, but was enhanced over time.

The Output Processing program had two key roles. First, it handled data that was specifically queued for it because of a reactive need to send data to a given output. For example, if someone made a data entry error or a controller queried for a specific aircraft's flight plan, the Input Processing program placed the resulting data in memory, where the Output Processing program would "find it" to format and send to the correct device. The Output Processing program also continuously prepared common outputs like flight data blocks and radar station status messages that were formatted once to a common memory buffer to be sent to many devices in bulk. For example, a new flight strip for an aircraft would be formatted and stored once, and then sent in sequence to every controller position with a relation to that aircraft.

Legacy

The 9020 is just one corner of the evolution of air traffic control during the 1960s and 1970s, a period that also saw the introduction of secondary radar for civilian flights and the first effort to automate the role of flight service stations. These topics quickly spiral out into others: unlike the ARTCCs of the time, the flight service stations dealt extensively with weather and interacted with both FAA and National Weather Service teletype networks and computer systems. An early effort to automate the flight service function involved the use of a teletext system originally developed for agricultural use as a "flight briefing terminal." That wasn't the agricultural teletext system in Kentucky that I discussed, but a different one, in Kansas. Fascinating things everywhere you look!

This article has already become long, though, and so we'll have to save plenty for later. To round things out, let's consider the fate of the 9020. SAGE is known not only for its pioneering role in the computing art, but because of its remarkably long service life, roughly from 1958 to 1984. The 9020 was almost 20 years younger than SAGE, and indeed outlived it, but not by much. In 1982, IBM announced the IBM 3083, a newer implementation of the Enhanced S/370 architecture that was directly descended from S/360 but with greatly improved I/O capabilities. In 1986, the FAA accepted a new 3083-based system called "HOST." Over the following three years, all of the 9020 CCCs were replaced by HOST systems.

The 9020 was not to be forgotten so easily, though. First, the HOST project was mostly limited to hardware modernization or "rehosting." The HOST 3083 computers ran most of the same application code as the original 9020 system, incorporating many enhancements made over the intervening decades.

Second, there is the case of the Display Channel Complex. Once again, because of the complexity of the PVD subsystem the FAA opted to view it as a separate program. While an effort was started to replace the 9020 DCCs alongside the 9020 CCCs, it encountered considerable delays and was ultimately canceled. The 9020 DCCs remained in service controlling PVDs until the ERAM Stage A project replaced the PVD system entirely in the 1990s.

While IBM's efforts to market the 9020 overseas generally failed, one reduced-size "simplex" 9020 CCC system was sold to the UK Civil Aviation Authority for use in the London Air Traffic Centre. This 9020 remained in service until 1990, and perhaps because of its singularity and unusually long life, it is better remembered as a historic object. There are photos.