At Monumental we’re bringing robotics to on-site construction, starting with bricklaying. Our approach isn’t a single heavyweight robot, but a coordinated fleet of small autonomous ground vehicles, each equipped for a specific part of the build. As that fleet scales, we lean heavily on techniques from typed functional programming to keep our fleet orchestration robust and maintainable

At the moment we’re running multiple deployments in parallel. On one site alone, ten robot teams are building four houses, bringing us to over 260 actuators moving in total. All at the same time. It’s a surprising amount of hardware to coordinate, and we’re only getting started!

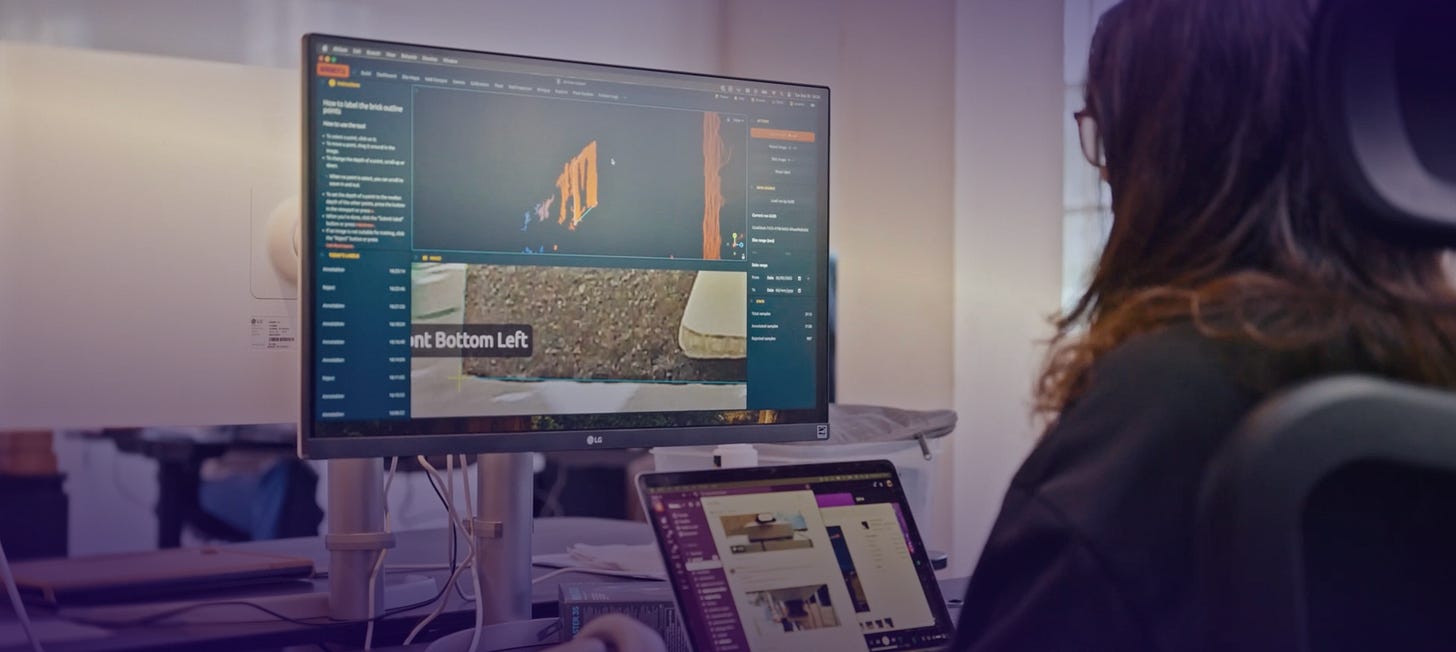

A few PLCs and some ladder logic won’t cut it at this scale. We use Atrium, our operating system for construction, to plan deployments and orchestrate build plans. In this post, we focus on how functional programming helps us express complex build plans and abstract away the hardware beneath them.

Our codebase is mostly Rust and TypeScript, with some occasional Python and C++. None of these languages are truly FP, but most are expressive enough to embrace the paradigm.

How do we use functional programming? Besides the common idioms of immutability, purity and higher-order functions we write a lot of embedded domain-specific languages. Mostly as large indexed sum types (enumerations), with one variant per supported action. Instead of writing imperative code directly, we use these DSLs to build up scripts as a datatype that we can write a separate interpreter for.

The DSL-as-datatype approach is really powerful, because having the structure of your code as a value gives us a lot of flexibility besides direct interpretation. We can do a lot more: we can control execution (pause, restart, rewind), run offline simulations, statically rewrite and optimize, log and profile runtime execution, and build introspective UIs. All of this without our domain specific code ever knowing about it.

DSLs are also great for overall code hygiene: a well defined and fully typed abstraction layer between our domain logic and our core platform.

In order to command our robots to build walls we write high level plans as scripts inside a domain specific language aptly called Plan. At the heart of this DSL is an algebraic datatype with a set of combinators encoding all the possible types of actions our plans can take. The datatype is recursive, because plan actions might reference or contain other plan actions.

We’ll start by showing a small example of the Plan type in TypeScript and slowly build up to more interesting examples step by step.

The Plan type is a tagged union with four actions: run a primitive effect, run plans sequentially, run them in parallel, or dispatch a plan based on the world state. Our DSL is generic and doesn’t make any assumptions about the environment it runs in.

Wrepresents the World. Our digital twin containing everything relevant on-site: robot state, wall geometry, environment reconstructions, and building bookkeeping.Erepresents Effects. The commands we can issue to robots. Only primitive plans produce effects; everything else is structure interpreted or simulated by the runtime.

To simplify writing code in our DSL we introduce a bunch of boilerplate smart constructors for every possible plan action.

Now we have enough to start writing simple plans. Let’s pick and place a brick:

The plan reads like a small script: inspect the current world, decide what to do next, combine sequential and parallel steps, and place the brick. The code itself doesn’t deal with execution details; it simply describes the structure of the work. Turning that structure into real behavior is left to the interpreter.

By this point we’ve already seen how plans can dispatch based on the current site state. Our DSL doesn’t include a built-in looping construct, but that turns out not to be a limitation. Using recursion and a small dyn-based helper, we can define looping ourselves:

With that in place, building an entire wall becomes straightforward:

This reads as “keep placing bricks until the wall is finished”, but with an important detail: the condition is evaluated against a fresh snapshot of the site on every iteration. Each step rechecks reality before deciding what to do next.

Plans are executed by a lightweight asynchronous interpreter. It switches over each plan tag, recursing into nested plans as needed. Primitive actions are delegated to an effect executor, while sequential flows, parallel branches, and world-driven dynamic dispatch are evaluated directly. The interpreter exposes the digital twin through a world variable, which each plan step can inspect.

A key design choice is keeping interpretation and execution independent. The interpreter walks the plan and determines the next action; the executor handles the real-world effect. This explicit boundary gives us a lot of flexibility.

This architecture gives us plug-and-play execution. The same plan can drive live hardware, run in a deterministic simulator, or be replayed for debugging:

The Plan DSL provides a clear separation between domain logic and orchestration. Domain code describes what should happen, while the interpreter is responsible for how plans are executed. This separation makes plans easy to test, simulate, and trace without involving real hardware.

Dynamic dispatch (via dyn) gives each plan step explicit, local access to the latest snapshot of the world. Decisions are made by pure functions over that snapshot, rather than through implicit global state or direct API calls. This keeps control flow visible and predictable.

Strong typing further constrains what plans can and cannot do, fencing off entire classes of errors at compile time. And because the DSL is generic and environment-agnostic, the same structure scales beyond the current use case. Whether that’s new robot types, new build processes, or entirely different domains.

What we’ve covered so far is just the foundation. The real system includes richer primitives: world-state updates for manual bookkeeping, synchronization between parallel branches, structured retries and recovery logic, local state variables and more. See this post’s appendices for a more complete listing.

One subtle but powerful mechanism is state zooming via functional lenses. This allows a plan to isolate a particular region of the world — for example, a single wall segment or robot subsystem — run a focused sub plan, and then cleanly stitch the updated state back into the full twin. This keeps complex orchestration code both modular and maintainable.

We’ll explore these patterns and more in upcoming posts.

The actual Plan type we use in production includes more variants than the simplified versions in the main post. Several of these constructors allow plans to return values, that can be picked up by the bind command making the structure effectively monadic.

We place the enumeration inside a small class wrapper. This gives us room for convenience methods and keeps plan construction readable without changing the underlying semantics. Here for example we put named/zoom/while/if directly on the class as a utility method. Crucially, we’re still only building a data structure, nothing executes until the interpreter runs it.

This appendix shows the minimal interpreter that executes our plans. It pattern-matches on each Plan constructor and applies the corresponding semantics. The interpreter uses a Var abstraction (essentially a reactive world-state cell) which allows us to read, update, and react to changes in the digital twin over time. All actual robot commands are handed off to an effect runner, keeping the interpreter focused purely on plan semantics rather than hardware details.