Yes. This is another attempt at criticising that impregnable castle that is Guns, Germs and Steel.1 The internet is full of reviews, summaries and, of course, those classy threads in Reddit. He has been widely prized, but also criticised in almost all fronts; history, human evolution, geography, and in many cases he seems to have been badly wounded, like in that review of Michael Barratt Brown, or the Mises Institute critical review on what they call Diamond’s pseudo-history. But when it comes to biology, he still stands tall and proud, like the Sphinx at Giza.

That is why I am still to find a proper critique of Diamond’s chapter on animal domestication. The more I read about the subject, whereas horses or aurochs, the more I find that there seems to be two camps: one completely ignores Diamond, as if avoiding the wrath of a Demigod; the other one cites his books and articles as priests citing Saint Matthew.

I am not a biologist, which kind of gives me the outsider’s advantage. It also puts me on a blind spot, as most non-specialists can easily get lost in the detail and interpret things in a completely mistaken way. I get that. But not being a biologist also allows me to approach the subject with an unorthodox point of view. I am irresolutely at peace with the prospect of being wrong about animal domestication. Probably Diamond has been right all along and that is why no one challenges his theory of animal domestication.

Diamond’s thesis about animal domestication is poured in chapter 9 Zebras, Unhappy Marriages, and the Anna Karenina Principle. But before I start talking about the subject proper, I need to say something about the literary analogy. The “Anna Karenina principle” has been used in all sort of situations and it wasn’t invented by Diamond. He may have made it widely popular outside the fenced pastures of literary criticism and other disciplines such as psychology and economics, but it’s definitely not his. I say this because people seem to attribute to Diamond all sort of ideas, when in reality what he has done, very well, is to summarise a huge variety of different ideas and to create a synthesis of what he thinks is the evolution of mankind. Another very popular myth is that he invented the continental axis hypothesis. The first person to mention it was Alfred Crosby in Ecological Imperialism.2 Crosby did not elaborate a full hypothesis though, and only mentioned the possibility of the north-south axis of the Americas to be one of many reasons for the slow pace of development:

“Why was the New World so tardily civilized? Perhaps because the long axis of the Americas runs north and south, and so the Amerindian food plants on which all New World civilizations depended had to spread through sharply differing climates, unlike the staple crops of the Old World, which by and large spread east and west through regions of roughly similar climates.” (p. 18)

Crosby wrote the above in 1986, almost a decade before Diamond’s first edition of Guns, Germs and Steel. It looks pretty similar to what Diamond proposes, right? What I find dishonest from Diamond is the fact that although he does cite Crosby in his literature, he never says this idea was first proposed by… which is kind of cheeky, to say the least.

Anyway, Chapter 9. Zebras, Unhappy Marriages, and the Anna Karenina Principle. Diamond presents here fourteen species as the backbone of animal domestication. Nine species are presented as minor, and five species are presented as major. We will focus now on the major ones: Sheep, Goat, Cow, Pig, Horse. These are the five species that have become ubiquitous around the world. The original range of these five species is located in Eurasia and this is very important because we must remember that Europeans, Diamond says Eurasians but he cannot mean anything other than Europeans, came to dominate the world and have guns, germs and steel. Yes, Genghis Khan, Darius and the Ottomans were not Europeans, but neither they arrive in ships to the Americas in 1492, nor created the Portuguese, Spanish, Dutch and British Empires, or gave birth to the United States of America, Australia and New Zealand. A fundamental milestone in the European triumph, or Eurasian if you prefer a more ambiguous term, was the domestication of animals and plants. In the case of plants, humans practically stumbled upon a massive wild granary in the Fertile Crescent as soon as they came out of Africa 40000 years ago. Some may point at the fact that, more precisely, this occurred after the Last Glacial Maxima (LGM), but it seems that the region in point wasn’t affected too much (please forgive my leniency if that wasn’t the case). There really was not much to do, wheat, barley, pulses were all there, not only growing across large expanses, but also being very productive already in their wild forms. It doesn’t come as a surprise then that recent discoveries have pushed back the date of early human use of cereals in the Levant to 23000 years ago, in a site called Abu Hureyra 1 in Syria. Please bear in mind that this doesn’t mean that humans started eating cereals 23000 years ago, it simply means that we know, for certain, that humans were using cereals by then; humans relationship with cereals could be much older, but we have not found evidence of older use, or further evidence from elsewhere to prove that this was the case across a large area in the Levant and the rest of the Fertile Crescent at the same date. As a comparison, the oldest evidence of cereal domestication, that is, people actually growing modern forms of wheat, is 10700 years old in a site called Tell Qarassa North, in southern Syria.

But animal domestication was different. We are not going to tell the individual story of each species here because neither does Diamond; what matters is what he considers the fundamental characteristics for a species to be domesticated. Here comes the Anna Karenina principle: “Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” In order to be happy, a marriage needs to succeed in many different respects, says Diamond. He then goes on to explain the characteristics of the Anna Karenina principle when applied to animal domestication:

flexible diet

appropriate growth rate

successful breeding in captivity

pleasant disposition towards humans

steady temperament

adaptable social hierarchy

In order to be domesticable, an animal must have all six characteristics. It cannot be fussy with food; it needs to grow fast; it must be able to breed in captivity; it must not panic or get completely infuriated by human presence and, finally, it must have a hierarchical social organisation whereby humans can occupy the vacant place of the alpha male leadership.

And here my dear readers, is where I think this gets rather tricky. The more I read the above “characteristics”, the more I have a weird feeling about it. Because what Diamond is describing under the banner of the ‘Anna Karenina Principle’ could be the result of thousands of years of selective breeding and not a series of traits shared among some wild animals. This is what I call a classic example of the Hempel’s paradox: ‘A case of a hypothesis supports the hypothesis.’ Yes, the black raven. “All Ravens are black” is equal to “All non-black things are non-ravens” and, therefore, a white shoe provides as much evidence that all ravens are black as a black raven does.

If we see one black raven, it doesn’t mean that all ravens are black, it simply is a piece of evidence supporting the hypothesis. Likewise, seeing 10000 black ravens still doesn’t prove that all ravens are black; it would only show us that we may be going in the right direction, but is not incontrovertible proof. But what happens if we see a single white raven? Well, we would have found incontrovertible, irrefutable and definite proof that not all ravens are black.

But a white shoe is another proof that all ravens are black, as all non-black things are non-ravens, right? There are two positions about this; a) a white shoe is a red herring (sensu Wood, 1967); b) a white shoe is not a red herring (sensu Hempel, 1967). Wood argues that the paradoxes of confirmation are spurious on the ground that one of the two assumptions underlying them is false; a white shoe does not represent evidence that all ravens are black. Hempel, on the other hand, argues that objects may have properties that make them confirmatory and disconfirmatory for a given hypothesis. A bird may be a raven and black, but may also have an albino for a sister; it would then prove and disprove the hypothesis that all ravens are black.

But in following Diamond’s argument, I feel that the best way of explaining my own convoluted argument is by using a literary analogy, as he has done with Tolstoi’s novel. Let’s call it the Chernobyl Principle, based on the HBO’s adaptation of Svetlana Alexievich’s Voices from Chernobyl. In one of the first episodes, a scientist called Valery Legasov is invited to a meeting of the Politburo presided by President Mikhail Gorbachev. Once the politburo has been briefed about the accident at Chernobyl in very rossy terms, Gorbachev adjourns the meeting, but Legasov objects, saying that he’s been worried about the mentions of black debris in the report which he believes is graphite. He also says that he is worried about the 3.6 roentgen radiation measure reported (one of the members of the politburo has liken it to a chest X-ray). As it turns out, the 3.6 roentgen magical number was the result of the low-limit dosimeters maxing out. The radiation was much higher indeed, but “they gave us the number they had.”

The Chernobyl Principle then, would dictate that what you see, does not necessarily equals to what you do not see. Diamond seems to be giving us ‘the number he had’, consciously or otherwise. According to him, Zebras have not been domesticated simply because they have evolved in an ecosystem overcrowded by predators, and therefore have become too aggressive, too twitchy, too suspicious (which, by the way, doesn’t explain the Zebras’ ducking reflex that makes them so good at avoiding the lasso). But what evidence do we have that the wild relative of the horse was not as wild as the zebra? Since the closest wild relatives of the modern horse have no descendants today, Diamond is supporting his characterisation of the horse as an ideal candidate for domestication on the heavily domesticated modern horse, not on historical or archaeological evidence, as the former is non-existent (the domestication of the horse predates writing) and the latter is scant. He basically says that the wild horses that roamed Eurasia’s steppes did not have to constantly deal with and be aware of cheetahs, lions and hyenas as zebras do on a daily basis in Africa; but he also forgets to mention that wild horses did have to contend with the most dangerous predator of all in Eurasia: humans. Since all we see around us are black ravens, we end up assuming that all ravens are black. But this may not have been always the case; maybe we pushed white ravens to extinction because we thought they were a bad omen.

But let us elaborate further the Chernobyl principle with a more relevant and appropriate example (we haven’t domesticated ravens after all). Aurochs are the ancestors of modern cattle and, as ancient horses, they went extinct. The big difference is that they lived much longer than horses in the wild and so, there is written evidence of their behaviour from Poland, where they supposedly existed until the High Middle Ages, I say supposedly because there is always the question mark of how wild they were by then. The following descriptions appear in Van Vuure (2005): “An aurochs is not afraid of humans and will not flee when a human being comes near, it will hardly avoid him when he approaches it slowly.”3 But then, the same author cites other passages from chroniclers where the European bison, held in similar conditions to the Aurochs in Białowieża forest, “does not run from humans; on the contrary, it stops when it is approached, and does not budge; it only attacks man when it is irritated, in which case it is fierce and dangerous.” It seems that both species behaved similarly towards humans. When chased, hunt or confined, they would become timid and shy, avoiding contacts with humans; when left to their own devices, they wouldn’t be afraid of humans. So here we have two species that behave similarly towards humans, eat the same, grow more or less at the same rate (Bisons reach adulthood in 3 years, while cattle does in 2), can breed while in captivity, have a more or less steady temperament (as long as you do not come across as a bull fighter), and have exactly the same social hierarchy. They also seem to adapt quite rapidly to the presence of humans, switching to a different social behaviour if they are chased or hunt. A similar situation has been reported with cattle that has been reintroduced to natural reserves in the Netherlands, Poland, Romania and Spain. European bison can be observed at very close range at Białowieża forest and they seem to behave exactly as they did 500 hundred years ago; if left alone, they would tolerate humans from a safe distance. Why is it then that Aurochs were domesticated but European bison was not if, according to Diamond, any species with the Anna Karenina Principle characteristics can, and has been domesticated?

Diamond offers further evidence to support the Anna Karenina principle by arguing that cultural obstacles against domestication cannot be put forward for the following reasons:

“… [the] rapid acceptance of Eurasian domesticates by non-Eurasian peoples, the universal human penchant for keeping pets, the rapid domestication of the ancient fourteen, the repeated independent domestications, and the limited successes of modern efforts at further domestication” (p. 176)

The first thing I have to say is that if I thought that Diamond’s original argument was weak, here I think that he is in even shakier and muddier territory. Once more, we can see here Diamond’s penchant for sweep generalisations at work. Let’s break and dissect the above paragraph:

Rapid acceptance of Eurasian domesticates by non-Eurasian peoples

The universal human penchant for keeping pets

The rapid domestication of the ancient fourteen

The repeated independent domestications

The limited success of modern efforts at further domestication

Rapid acceptance of Eurasian domesticates by non-Eurasian peoples: Here Diamond seems to confuse adoption with imposition. I do not want to expand too much on this because I personally believe that the victim argument used by the political left has been over-exploited. This does not mean that is not partially correct. In the process of enforcing the land grab that we call the Discovery of the Americas, the traditional ways of life of Native Americans were profoundly modified, when not completely annihilated. The whole process was merely a forced acculturation. Diamond’s argument of rapid acceptance of the Eurasian domesticates is tantamount to say that the swift spread of Catholicism among native peoples in the Americas was a divine sign of its righteousness; or that the adoption of the conquerors’ languages is a sign of the superiority of Indo-European languages over the local languages.

I would also add here that the “success” and wide adoption of Eurasian domesticates in the Americas is also a function of ecological fitness. The disappearance of Megafauna in the Americas, either caused by overkill or climate related changes in the ecosystem, left huge vacant expanses ready to be occupied by new, large ruminants such as domestic cattle, horses or sheep. That was the case in the Argentinian Pampas, where feral horses spread like fire once they were brought from Europe and accidentally escaped their enclosures. Likewise, the hunt of American bison and their consequent dwindling numbers in the large expanses of North America left a vacant niche ready to be occupied by Eurasian cattle.4

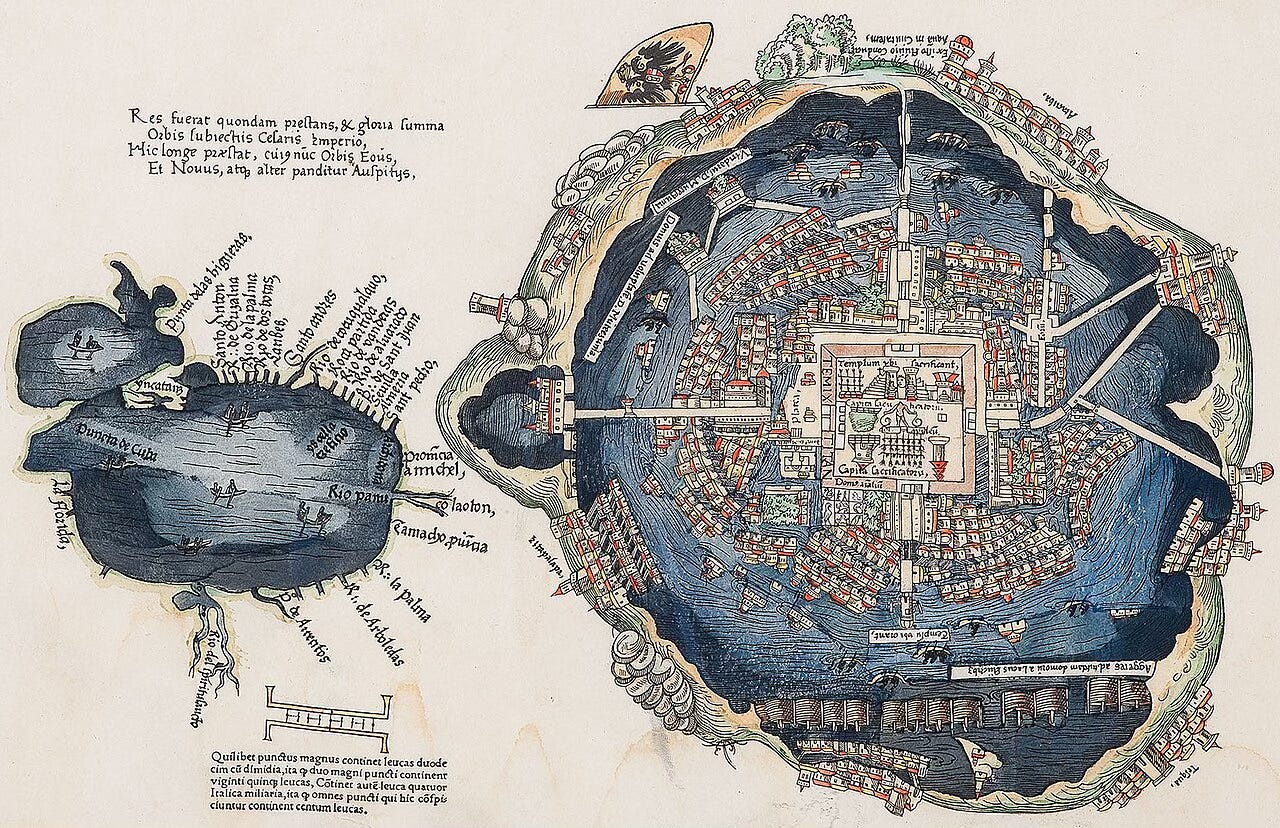

Finally, the adoption of the horse by Natives in North America may have been more of a survival adaptation to the constant encroaching of European colonists than the gracious acceptance of an alien animal as a mean of transport. I always find amusing the obsession of the Western world with animals as beasts of burden, when there are myriads of examples from ancient societies across the world of large scale engineering feats where no animals were used as aid. Think for example of the Easter Island Moais, or the construction of Machu Picchu or the Mayan monuments in Mesoamerica. We usually declare these monuments as engineering mysteries. One has only to see a map of the Aztec capital, Tenochtitlan, and appreciate that the canals and chinampas (small orchards) were a very elegant solution to the logistical problems of a big city devoid of other means of transport.

The universal human penchant for keeping pets: Diamond assumes here that all human societies see animals as an accessory to whatever is that humans do. They are either food, companion or amusement. Not long ago, we used to parade human beings with deformities or disabilities as amusing objects from a cabinet of curiosities too. But anthropological research in South America has shown that: “indigenous Amazonians don’t domesticate animals because it doesn’t make any sense to them.”5 Furthermore, many aboriginal peoples, and this is particularly so in the Amazonian context, believe that animals (both predator and prey) are people. According to this logic, there is a profound dilemma in eating something that, like us, has a soul. It may also have consequences. In the Amazon basin, even the ubiquitous dog was absent as a pet until the 20th Century. So, despite the profuse presence of pets among the Amazonian tribes, this cannot be taken as a precursor to domestication.

Furthermore, Native Americans, who never experienced horses or cattle prior to the European arrival, may have not seen these species as they would see the ones that conform their cosmography. Horses may have been seen as extensions of the Europeans, with no ontological connection to their system of beliefs.

The rapid domestication of the ancient fourteen: it is true that most of the species described by Diamond were domesticated in the last 10000 years, but this is also true for almost everything related to modern humans: Agriculture, sedentarism, writing, religion, all occurred within the last 10000 years. As a counter argument, we can say that dogs were domesticated way before that, and as not much occurred outside this 10000 years, it is really a poor argument in favour of domestication.

The repeated independent domestications: This is another area where Diamond performs poorly, with a particular use of cherry-picking to enhance his argument. He mentions the domestication of cattle in India, Southwest Asia and, possibly North Africa as a proof of independent domestications. But with the exception of Southwest Asia, which I am completely ignorant of, I have been told countless of times while reading Guns, Germs and Steel that Eurasia is a single landmass that has facilitated the spread of animals, technologies and plants. Diamond has also explicitly written in his book that he considers North Africa part of Eurasia. So, why does he treat Eurasia as a singularity in some cases, as in the continental axis hypothesis, but breaks it up when it suits his argument, as in domestication? Isn’t the domestication of Aurochs in India, or in Europe part of the same story? That of the superiority of the Eurasian peoples, partly due to the axis orientation and so on? How independent are these domestication events? What about examples of repeated domestications outside Eurasia? None worth mentioning in Africa, the Americas or Oceania? The multiple domestication of dogs both in Eurasia and in the Americas is also a very disputed argument, as ancient DNA studies have shown that the dog entered with humans to the Americas. This does not preclude the domestication of American species (way too complicated to cover succinctly here), but it does qualify domestication of the dog in the Americas to the fact that Paleoindians already had a coevolutionary relationship with wolves prior to the entry to the Americas.

The limited success of modern efforts at further domestication: Here I have to go back to the bison/Aurochs dichotomy. Diamond dodges the bison issue by literally omitting the European bison from his chapter on domestication altogether, and mentioning American bison only four times. What does he say about the American bison? Literally nothing:

“In the 19th and 20th centuries at least six large mammals—the eland, elk, moose, musk ox, zebra, and American bison—have been the subjects of especially well-organized projects aimed at domestication, carried out by modern scientific animal breeders and geneticists. For example, eland, the largest African antelope, have been undergoing selection for meat qual- ity and milk quantity in the Askaniya-Nova Zoological Park in the Ukraine, as well as in England, Kenya, Zimbabwe, and South Africa; an experimental farm for elk (red deer, in British terminology) has been operated by the Rowett Research Institute at Aberdeen, Scotland; and an experimental farm for moose has operated in the Pechero-Ilych National Park in Russia. Yet these modern efforts have achieved only very limited successes. While bison meat occasionally appears in some U.S. supermarkets, and while moose have been ridden, milked, and used to pull sleds in Sweden and Russia, none of these efforts has yielded a result of sufficient economic value to attract many ranchers.” (p. 180) My emphasis.

So, basically he is admitting, reluctantly though, that the issue with these programs is not that they have failed, but rather, that they haven’t attracted sufficient interest from farmers due to economic reasons. So, yes, according to this logic, they are of limited success, but how can he cite this as support for the Anna Karenina principle? Isn’t the occasional presence of bison meat in the supermarkets proof that bison can and have been successfully domesticated? The species may still look pretty much as the wild form that once roamed the prairies in their millions, but this is because the heavily domesticated forms of cattle that we grow as food have taken thousands of years to materialise, and even so, some specific breeds still resemble the primeval traits of the ancient Aurochs. Next time you see a Toro de Lidia, the Spanish fighter bull, pay attention to the specific shape of the horns and the athletic figure. That animal is an Aurochs in miniature, particularly at young age. Is it a coincidence then that this cattle breed has been particularly chosen due to his temperament for the Corridas de Toros? It seems to me that this is an ancient trait that survived in the remoteness and inaccessibility of the Iberian countryside and, once discovered, has been preserved not for food but for entertainment, rather than developed in the modern sense?

I want to finish this essay by asking one question about domestication that bothers me the most: what if we have been chosen by few, or ALL these domesticated species as a survival strategy? In other words, who has been domesticated here? I cannot stop thinking about that nasty parasitic fungus (Ophiocordyceps unilateralis) that transforms ants into zombies, the fruity organ protruding from the ant’s brain while still alive and conscious, when I see people walking their pets on the streets. Think about it, here you are in front of the most successful predator you have ever come across (humans), your chances of surviving this onslaught are truly slim; there is no chance to hide or run. What do you do? Do you let your pride to drag you to your tomb, or do you adapt? By offering to humans what they want, these species may have had increased their chances of survival enormously. They offer us proteins, company, assistance, early warning, transport, and so on; in turn they are showered with food, protection against predators and diseases, and plenty of habitats where to thrive.

This is even more obvious in our symbiotic relationship with dogs and cats, who most likely were attracted to human settlements by food waste and/or prey, as it’s the case of high rodent concentrations around grain storage. In both cases, humans may have neither elicited the contact, nor displayed any direct intention of domesticating the species. Only with time, this coevolutionary process would end up benefitting both species, when humans realised that wolfs could help them track and hunt large herds of herbivores, and cats could alleviate the loses caused by rodents. This, of course, is all speculative as there is no evidence to support it, but in India, Leopards are now attracted to large cities by the abundance of stray dogs; it remains to be seen if humans will tolerate leopard’s presence in a not-too-distant future to maintain strays populations in check.