A comprehensive review of the Samsung Odyssey Neo G9 and the super ultrawide experience

68 min readTable of contents

- The hardware

- Productivity and other desktop use

-

Gaming

- You need a pretty powerful rig for that, right?

- Game support (or lack thereof)

- First and third person games: mostly great

- Bird’s eye, top-down and isometric games: sometimes actual gameplay benefits!

- Side scrollers and other games: wild west

- Some assembly required

- The distortion problem

- Multitasking while gaming

- Gaming summary

- Other random thoughts and observations that didn’t fit anywhere else

- Summary

Back in early 2023, my trusty 27-inch Samsung CHG70 monitor was on its last legs. This once fancy flagship model — which I had bought in November 2017 — had been slowly dying for a couple of years. The issue was that the picture would be partially or completely garbled, covered in horizontal glitchy scanlines, which would sort themselves out after the monitor had warmed up for a while. The first encounter was in 2020 after I had been away from home for a couple of weeks. In the following years, this became more and more frequent, and by late 2022 the issue was present every time the monitor had been off for more than 15 minutes. It was technically still fully functional, just rather inconvenient to use.

But as 2023 rolled around, I had finally had enough and decided to get a replacement. My initial plan was to get one of those new fancy OLED displays, as they were starting to become more affordable and less prone to self-destruction via burn-in. I had fallen in love with my OLED TV, and all of my phones for the past decade had had OLED displays as well. The Alienware AW3423DW had been released the previous year and it received pretty good reviews with some major caveats, such as very limited max brightness with an aggressive ABL, ugly text rendering due to the subpixel layout, and the still very real risk of permanent burn-in.

However, a surprise deal at a local retailer made me change my mind. The Samsung Odyssey Neo G9 was normally priced at around 2,000 euros, but they were selling the remaining stock for a mere 1,400 euros each. This was a deal I could not refuse, so I pulled the metaphorical trigger and ordered one of these behemoths. It’s an LCD, but not just any old LCD: it’s an aggressively curved super ultrawide 32:9 aspect ratio VA panel with 2,048-zone full-array local dimming, running at a resolution of 5120x1440 at up to 240 Hz. And it’s even capable of pretty respectable HDR performance, unlike my previous main monitor which — despite technically supporting it — was completely incapable of reaching the required contrast and brightness levels. Or in less nerdy terms: this monitor is monstrously wide, bright, contrasty, and fast.

This is kind of a review of my experience with this monitor after a bit under 3 years of near-daily use. But the monitor isn’t really the main focus here; there’s little point in reviewing a monitor that was already outdated when I bought it, and it hasn’t been available for purchase for a long time. The monitor isn’t the most interesting part of my experience; rather, it’s the experience and struggles of using such an extreme aspect ratio for work and play. But I have things to say about the monitor as well, so let’s get that out of the way first.

The hardware

I am not a hardware reviewer, so my focus is on the user experience rather than benchmarks and technical measurements. If you’re more interested in that, I can strongly recommend the RTINGS review which goes into uncomfortable levels of detail about the monitor’s features and performance.

Size

The monitor is — as previously stated — absolutely enormous. However, as with most things, the largeness is relative. While it’s objectively gargantuan for a single panel, it actually takes up less space on my desk than my previous setup of two 27-inch 1440p monitors side by side. And it comes with the same exact number of pixels as the two displays combined, so the screen real estate is technically (though not experientially) the same — more on that later.

Design

The back of the monitor is made from white plastic, with random sci-fi detailing and some kind of a lighting effect (which Samsung calls “Infinite Core Lighting”) in the center bit that I was luckily able to disable immediately. It has a kind of Y2K retro-futuristic gamer sci-fi look that reminds me of early 2000s graphics card box art. That is largely irrelevant as I have the back of the monitor facing the wall, as I’d imagine most people do. The front side is mostly black plastic with fairly thick bezels. It looks like a monitor, except for the bits that don’t.

Build quality

The build quality is mixed. The plastics feel nice, and the stand is solid and surprisingly small for such a heavy piece of kit. The buttons and the joystick feel responsive and the indicator light is not too bright. All mostly good things.

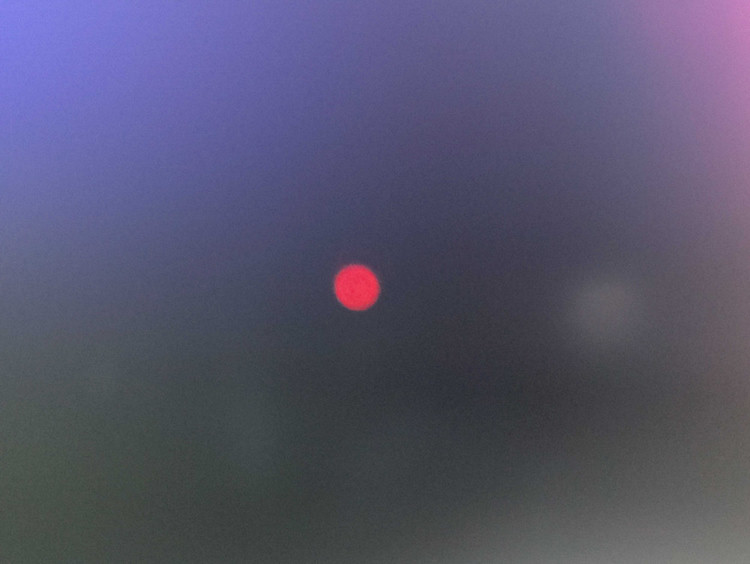

However, there’s a big caveat: my monitor has had a stuck pixel since day one. It’s a bright red pixel near the left edge of the screen, a bit below the center. It took me a day to notice it, and at that point I couldn’t be bothered to go through the hassle of packing it back up and returning it. From what I’ve gathered, this is not an uncommon issue with this model, and in a sense I was lucky to get just one stuck or dead pixel. Nowadays I can barely notice it; it’s not visible against a white background, and local dimming makes it a bit less obvious against darker backgrounds as well. Still, it’s a major blemish on an otherwise mostly competently made premium product. You’d think that for a monitor this expensive, it would be worthwhile to have someone have a look at it before sending it out to the customer.

Inputs and connectivity

The monitor has one DisplayPort 1.4 input and two HDMI 2.1 ports, which is adequate but not ideal, and here’s why: only the DisplayPort input is capable of running the monitor at its native resolution at 240 Hz. The HDMI ports are limited to 144 Hz, because apparently the Neo G9 does not support DSC with HDMI. It’s not a huge issue — chances are you can’t run most games at more than 144 FPS at this resolution anyway — but at this price point, I’m not very accepting of compromises like this. Two DisplayPort inputs would have been preferable, and a USB-C input would have also been nice to have.

When I first got the monitor, I was having some issues running it at 240 Hz without dropouts or flickering. There were occasional flashes (maybe 50 to 400 ms) of black screen, especially when jumping between different windows with Alt+Tab. I think this might have had something to do with display stream compression not being able to keep up when content changes instantly, but then again games render entirely new frames all the time and I don’t recall seeing this issue in any game, only on the desktop. Regardless, after trying different DisplayPort cables and failing to get any improvement, I gave up and dropped the refresh rate to 120 Hz, which had no issues at all.

But then, writing this, I realized that I’ve actually been running the monitor at 240 Hz for a fairly long time, and I haven’t seen the issue in a while. I don’t remember exactly when I switched the refresh rate back up, but it was probably after I upgraded my GPU from an RTX 3080 to an RTX 4080 Super in early 2024. It could have been a GPU issue after all, either hardware or driver-related. Or maybe I just switched to a better and / or shorter cable at some point. It shall remain a mystery.

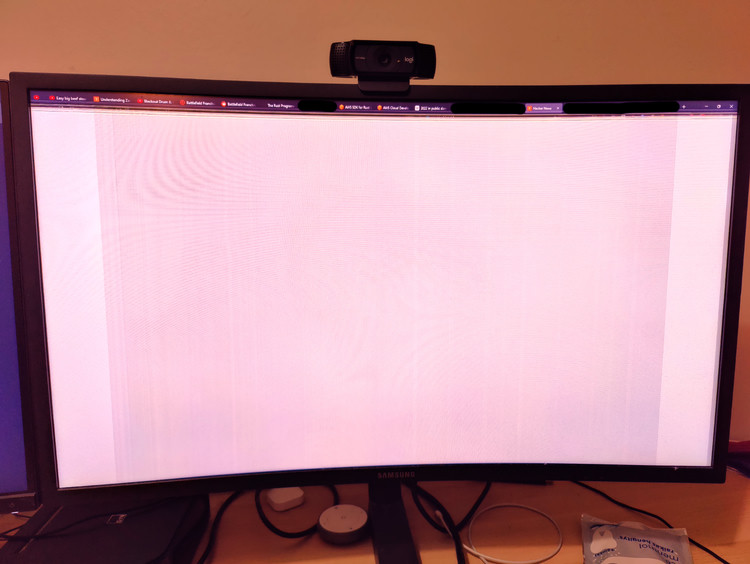

I still get random connectivity issues with my M2 MacBook Pro, which is connected directly via HDMI. Occasionally, maybe twice a week, the picture goes black for one or two seconds, and then either comes back as normal or becomes glitched in an interesting way:

The issue is easily fixed by replugging the HDMI cable or by opening and closing the Mac’s lid to make it re-detect the display. The glitches don’t happen in the panel (unlike with my previous main display), as the OSD still looks fine when the issue occurs. It could be a bug in either the monitor or the computer, or just a bad cable. A minor annoyance, not a dealbreaker.

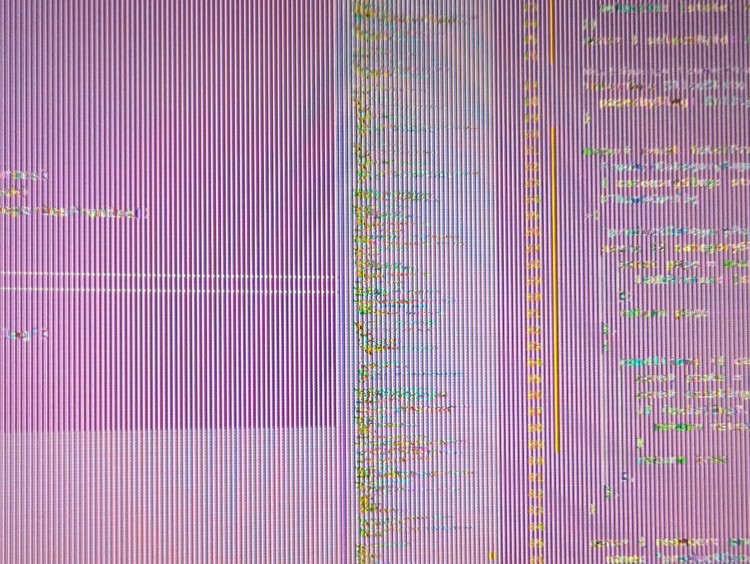

Similarly, switching from the HDMI input (connected to the Mac) to the DisplayPort input (connected to my gaming PC) sometimes causes the display to just show horizontal rainbow scanlines, regardless of what the PC is outputting.

This is fixed by restarting the monitor, and it’s almost certainly a bug in the monitor’s firmware; I’ve only experienced it when switching inputs, never when the computer starts or wakes from sleep.

Features and user experience

The user experience is a more complicated matter. Overall, I think it has several conceptually good features bottlenecked if not ruined by baffling design choices and cost-cutting in odd places, and also some features that don’t seem to fit a flagship gaming monitor at all, at least the way they are implemented here.

There’s an integrated USB hub with two USB-A ports in the back, which are not very conveniently located. At this price point, at least nowadays, I would expect at least one USB-C port with power delivery, and possibly even a built-in KVM switch. I use the monitor with my M2 MacBook Pro for work and with my gaming PC the rest of the time, so I have a separate 4-port KVM switch cluttering my desk. The monitor’s USB ports are useless to me.

Speaking of useless features, I am somewhat confused by the three buttons on the bottom edge of the monitor, right next to the joystick used for navigating the on-screen display. I had assumed from marketing materials that these would be programmable quick-access buttons for switching between different input sources and / or picture settings, but in reality they are hardcoded to “genre-specific” picture modes (like RTS, FPS and AOS), which basically ruin the picture quality by applying very aggressive contrast and sharpness adjustments. I would imagine the display engineers who worked very hard on the panel would be devastated to see someone actually use these modes, but they were still given dedicated buttons that cannot be used for anything else. What?

Similarly, though less annoyingly, I also wonder what a 3.5mm headphone jack is doing on the back of a high-end display. I’m sure someone somewhere might find it useful, but if you are interested in a high-end gaming experience, chances are you also have either a dedicated DAC / amplifier or at least acceptable onboard audio from your computer. Regardless, they could have at least put it in a more accessible location, like the bottom edge or side of the monitor — and also done that for the USB ports while they were at it.

There’s a picture-by-picture feature I was originally somewhat excited about: you can virtually split the monitor into two displays, either in a 1:1 or 2:1 / 1:2 configuration. This would in theory make multitasking slightly easier, as window management on such a wide display can be a bit of a pain. My main use case would be to run a game on the bigger portion of the screen, and have Discord or a web browser open on the smaller side. However, there are several limitations: you need to connect two separate cables to the monitor to use this feature, and most of the high-end gaming features (variable refresh rate / G-Sync, 240 Hz, HDR, local dimming) are simply not available in the picture-by-picture mode. It’s purely for work and not intended for serious gaming. So, I haven’t really used this feature much after initial experimentation.

DisplayPort has a feature called Multi-Stream Transport (MST). As the name kind of implies, this enables one cable to transport multiple independent video streams, meaning you can connect multiple monitors to a single DisplayPort output. This is usually accomplished either via daisy-chaining (connecting one monitor to another) or via a hub, which splits the signal into multiple outputs.

While daisy-chaining is a pretty common feature on higher-end business monitors and graphics cards have supported it for 10-15 years, as far as I can tell there is no monitor that uses MST to implement picture-by-picture with a single cable. This seems like an obvious application of the technology, but maybe there’s a reason no one has done it yet.

The on-screen display (OSD, the settings menu) is basically the same it’s been on Samsung monitors for about a decade now, and it’s mostly fine. As expected, it’s full of bullshit Made Up Technologies™ dreamed up by the marketing team — who’s excited for Off Timer Plus? Every setting has a built-in description, which is good in theory, but many of them are pretty confusing and either poorly translated or written by someone who doesn’t actually know what the feature does either; for example, the setting labeled VRR control says “Sync GPU provides optimal gaming conditions”. Admittedly, this is standard stuff for monitor OSDs, and after the initial setup I haven’t had to interact with it much, other than to change inputs up to a few times a day. Not great, not terrible.

Panel and image quality

But now for the main event: the panel. I can forgive many blunders if the image quality is good, and luckily it very much is. It is simply the best display I’ve ever used.

It doesn’t have the perfect blacks of OLED, but VA combined with FALD gets surprisingly close. Local dimming can be prone to blooming — and it is, in fact, unavoidable, unless every pixel has its own backlight (which is what OLED is) — but Samsung’s engineers have performed some magic to almost completely eliminate it, as long as you are looking at it from a typical viewing angle.

I’m really happy with color reproduction, contrast and peak brightness, and the pixel density is at least sufficient for both gaming and productivity use at the native resolution. The high refresh rate is a delight whenever I can reach it in games, though admittedly going past 144 Hz (which is what my previous monitor supported) doesn’t make a huge difference for me personally.

But it’s not without some minor issues.

Local dimming looks excellent with HDR content, but games with good HDR implementations are still relatively rare on the PC — more on that later. And unfortunately, enabling full local dimming (“Low” or “High” setting) in SDR mode (which is what you’ll likely be using most of the time) looks pretty bad, with a busted gamma curve that makes every grayscale tone look slightly wrong. As a result, I have set local dimming to Auto mode, which is supposed to disable local dimming with SDR content, and to automatically enable it with HDR.

However, the Auto mode doesn’t actually work as documented. As an experiment, I created a completely black image and set it to cover most of the screen. In Auto mode, the mouse cursor looks much darker when hovering over the black background, which is a sign that local dimming is active — even though HDR is not enabled. Explicitly disabling local dimming makes the cursor brighter, but also makes the black levels noticeably worse. Setting local dimming to Low or High doesn’t seem to improve the black levels, but they do boost peak brightness levels while ruining gamma as previously mentioned, whereas gamma looks correct in Auto mode. So I have no idea what the hell Auto is actually doing, but that’s the mode I’ve been using day-to-day for the past few years.

There is apparently a firmware update (my monitor is running version 1011, latest is 1015) that improves some aspects of local dimming with HDR content, but at least according to Reddit, it makes it even worse with SDR. So I’m not planning to update the firmware any time soon.

Some colors, especially light blues and oranges (such as the tone of orange used in the Hacker News logo and header) have subtle yet visible horizontal scanlines when looked at closely. It’s not a huge issue, but it’s interesting how it only happens with very specific colors. It’s not noticeable in games or other media, but in desktop use it can be a bit distracting.

And there’s, of course, the aforementioned stuck pixel, which is a shame on such an otherwise excellent panel.

Odyssey Neo G9 summary

Overall, the Samsung Odyssey Neo G9 is both impressive and frustrating. It’s the most impressive monitor I’ve ever used, but it’s still mired in issues and compromises I wouldn’t expect from a top-tier product. The 600 euro discount made it a worthwhile purchase, but I would have never paid full price for it. It hasn’t shown any signs of hardware failure so far, so I hope it will last for many more years to come.

There’s overall a bit of a mismatch between the premium price point and some of the design choices. Despite the gamer-y aesthetic and high-end panel specifications, the rest of the features are surprisingly basic and unpolished, and not dramatically different from most entry to mid-range monitors made in the past 15 years. It does what it sets out to do well — to be a top-tier super ultrawide gaming monitor — but it doesn’t really impress in any other aspect.

Not having better support for productivity use — such as a built-in KVM switch, USB-C input with PD, or better picture-by-picture support — seems like a missed opportunity, especially considering this monitor was released during the pandemic when a lot of people who bought it were likely using it for both work and play. I know very little about how monitor design and manufacturing works, but I would assume the vast majority of manufacturing cost goes into the panel itself (especially the FALD backlight), and things like USB ports and headphone jacks are basically free in comparison. There are some monitors which go all out on productivity features, such as this model from Dell, which has a KVM switch with lots of USB-A ports, USB-C with PD, and even an RJ45 Ethernet port for wired networking. Admittedly it’s also rather terrible in most other aspects, but I would imagine it’s not physically impossible to combine a great panel with great auxiliary features.

It’s the best display I’ve ever had. I hate it. I love it. I regret buying it. I wouldn’t change it for anything else — except maybe the OLED version from 2023, which is now available for 1,500 euros even without a discount.

Productivity and other desktop use

When I got this display, I had used two 27-inch 2560x1440 monitors (the aforementioned Samsung CHG70 and some Dell business monitor) at home for about 5 years. With the exact same number of pixels and identical pixel density, how different could the experience really be?

Multitasking

While the total screen area is the same with both setups, the way those pixels can be put to practical use is very different. Keyword: bezels. The operating system merges the two displays into one large virtual display, but it cannot change the fact that there’s a bit of plastic separating the two halves. While windows can technically span multiple displays, that almost always results in text, UI elements and content getting cut off in awkward ways. So the maximum size of a single window is the size of one display, and window boundaries are practically forced to align with the physical bezels.

With a single ultrawide monitor, multitasking is much more free-form. Windows can take arbitrary fractions of the screen width, with no care where the window boundaries fall. My usual setup is to arrange windows to split the space into three different sections, and to tweak the relative sizes of those sections depending on what I’m doing. For example, when working on a front-end web development task, I’ll usually have my IDE taking up a bit over half of the screen (usually with two files, a terminal and a file listing or LLM chat panel), and two browser windows — one for Figma and one for the app — sharing the remaining space.

It’s not all sunshine and kittens, though. With a more traditional monitor setup consisting of one or more 16:9-ish displays, partitioning the screen for multiple applications is an optional extra, mostly relevant for power users. With a monitor like this one, it’s basically mandatory. Apart from gaming and some productivity applications — namely FL Studio, DaVinci Resolve and Resolume Avenue — I have encountered very few applications and zero websites that can be reasonably used in a maximized state with a 32:9 aspect ratio.

In my experience, basic multitasking was easier with two separate displays, as I could just maximize windows to each display without much drama. This is the reason why the Neo G9 has a picture-by-picture mode, after all. As a result, I spend more time each day managing window sizes and positions than I ever did with my previous monitor setups — though the multitasking experience itself is superior with the additional flexibility. It’s not a lot of time in the grand scheme of things, but I wouldn’t recommend a monitor like this to someone who’s allergic to window management.

I use macOS for work and Windows for pretty much everything else, so here’s how I deal with the situation on each platform.

Windows

I’ve been a huge fan of Aero Snap ever since it was introduced in Windows 7, but with an ultrawide monitor it’s no longer very useful. Its primary use case is to snap windows to halves of the screen, but on an ultrawide half is usually too much. I did try using FancyZones from Microsoft’s PowerToys suite for a while, but it just never became part of my workflow. It could be argued that FancyZones’ core functionality was made redundant by Windows 11’s improved window snapping features, but I never really got into using those either.

Instead, I use a little utility application called AquaSnap, which makes several improvements to Windows’ window management features, such as making windows snap to each other’s edges, making windows transparent while they are being moved, and the ability to resize multiple windows simultaneously by dragging the shared border while holding down Ctrl. Apart from window edge magnetism (I wish every window manager / operating system had this) the core feature set is very similar to Windows 11’s built-in window snapping; the main difference is that in AquaSnap the layout is implicitly defined by the current set of open windows, while in Windows 11 you have to explicitly select a layout from the snap assist UI. I could probably get by without AquaSnap, but I’ve been using it since 2020 and how it works now is how I expect window management to work in Windows.

I also enabled Automatically hide the taskbar to maximize vertical screen real estate. With two monitors I had the taskbar only on the primary display, which gave the secondary display a bit more vertical space. It’s a shame Microsoft killed the vertical taskbar in Windows 11, as it seems like a natural fit for ultrawide monitors. On the other hand, Windows 11’s centered taskbar is at home with such a wide aspect ratio — it’s neat that I don’t have to constantly turn my head just to access the Start menu.

macOS

Window management on modern macOS is a bit of a mixed bag. macOS Sequoia introduced native window snapping (or tiling in Apple’s parlance), and it’s actually quite good. It feels more robust than Windows 11’s snapping, which forgets your layout if you accidentally move or resize any of the windows involved the wrong way.

It’s a shame that it’s almost useless for displays bigger than a typical laptop screen, as it can only deal with either two windows side by side, or four apps in a 2x2 grid. Try to split the screen into three or more sections — even by manually moving and resizing windows — and the functionality enabled by tiling (like the ability to resize multiple windows simultaneously) simply ceases to exist.

It’s not all bad, though: window border magnetism is built into the OS, and as far as I remember it’s been there for a good while. It doesn’t feel quite as good as AquaSnap’s implementation on Windows, but it’s certainly better than nothing.

I do have Magnet installed on my work computer, but truth be told, I’m not really a power user. Unlike the built-in snapping feature, it does support snapping into thirds and sixths of the screen, but I almost never make use of it; like with FancyZones, I just never got into the habit of using it daily. I just use the basic snapping functionality to make a window take up the full height, and then manually resize and move it where I want it. Window magnetism makes this not too painful.

I also have the Dock set to auto-hide, but that’s not really specific to this monitor.

More is more

There’s a saying in Finnish: “nälkä kasvaa syödessä”, literally “hunger grows while eating”, meaning that once you get a taste of something good, you want more of it. That pretty much summarizes my experience with ultrawide monitors for work and productivity use. Even though the monitor occupies most of my horizontal field of view and basically all of the space on my not-very-small desk, I still can’t get everything I need on the screen at once. I always have to compromise when using my standard IDE + app + Figma setup; one or two of those windows are always uncomfortably small if I don’t overlap them.

What I really want is a slightly higher pixel density. While 109 PPI is pretty good as far as desktop monitors go, it’s a far cry from the ridiculous 254 PPI offered by my M2 MacBook Pro. And Samsung does have a solution for this problem: the Odyssey Neo G9 57-inch (G95NC) from 2023, which is similar to my monitor in most aspects, but it boosts the resolution to a completely unreasonable 7680x2160 at a slightly larger physical size. At first glance it might not seem like a huge upgrade, but it actually more than doubles the number of pixels. This results in a pixel density of 140 PPI, an improvement of about 28%. I’ve only seen it in person once at an electronics store, but I would imagine that I would be able to use it comfortably with minimal scaling, which would provide quite a big boost to screen real estate. It even comes with a 2-port KVM switch! But it also costs 2,600 euros, offers worse HDR performance than the 2021 Neo G9, and requires an input source with DisplayPort 2.1 support (RTX 5000 Series or M4 Mac) to even run it at full resolution and refresh rate. But I don’t think I will be upgrading any time soon.

Reflecting on different monitor setups I’ve used for work over the years, I think the most productive combination was a 21:9 ultrawide monitor (3440x1440) paired with the Mac’s built-in display, ideally with the laptop propped up on a stand to vertically align the two displays. While there’s some inherent awkwardness in using two wildly different monitors, at least for me this was a great combination. The ultrawide can be dedicated to the main task at hand, while the laptop is used more flexibly to jump between different applications as needed, especially with the help of virtual desktops. The Mac’s high pixel density (which devotees of the Church of Apple call Retina) means there can actually be more usable space with this setup than with a single super ultrawide monitor, depending on scaling settings, of course.

Gaming

Finally, let’s talk about playing games in 32:9 on this 32:9 gaming monitor. While I will be covering some aspects specific to the Neo G9, talking about this monitor isn’t really the main point here.

While all of my experiences of playing in super ultrawide are based on this specific monitor (though I have used multiple 21:9 monitors in the past), I think it’s far more interesting and useful to talk about playing at wider aspect ratios in general. Practically all mainstream games are designed for 16:9 first, and console games don’t even support anything else. Not to mention older games from the early 2000s and before, for which even widescreen can be a challenge. How do games handle the wider viewport, from technical and design perspectives — if at all? How does it change the subjective experience of playing a game? Why does Half-Life 2’s FOV slider lie, and why is that a good thing, actually? Is it ultimately worth it?

You need a pretty powerful rig for that, right?

The answer is: yes, but not as much as you might think. In most mainstream games, the rendering resolution is the single biggest factor affecting game performance; the more pixels the game needs to render, the harder the GPU has to work. 5120x1440 is a lot of pixels, about 7.4 million of the little guys, and that is quite obviously double the pixel count of a single 16:9 2560x1440 display. But to give it further context, 4K (3840x2160) is about 8.3 million pixels. So it definitely requires a powerful GPU to run games at high settings at good frame rates, but it’s actually a bit less demanding than 4K, which even consoles have been able to handle (with generous amounts of upscaling and other tricks) for several years now.

But it’s a bit more complex than that. 4K monitors, especially ones sized 32 inches and below, have such a high pixel density that in my opinion rendering games at the native resolution is almost completely pointless. The pixels are so small that the difference between 1440p and 4K is barely noticeable unless you are doing close-up side-by-side comparisons. Especially with modern upscaling techniques like Nvidia DLSS and AMD FSR (4+) you can really crank the rendering resolution down without losing much visual fidelity. While 4K TVs are obviously bigger, they are also almost always viewed from much further away, meaning you can get away with even lower rendering resolutions with a good upscaler.

But since this monitor is effectively two 27-inch 1440p monitors stapled together, you can’t go quite as hard on upscaling as with a 4K display; whatever resolution scale looks good on a 1440p panel also works here. I’ve found that DLSS Balanced mode (58% resolution scale) is acceptable in most games, but Quality mode (67%) is sometimes a noticeable improvement. Meanwhile, it’s pretty common to see games being run at 4K with DLSS Performance mode (50%) with relatively little loss in visual quality.

So in summary: compared to a 4K monitor, this one is sometimes easier and sometimes harder to run, depending on the game, viewing distance, monitor size and personal tolerance for upscaling artifacts.

My PC has an RTX 4080 Super paired with a Ryzen 7 9800X3D, which is sufficient but not exactly overkill for this display. I run most modern AAA games with a mix of high and ultra settings with ray tracing enabled (though rarely maxed out) and with DLSS either in Quality or Balanced mode, and that usually results in frame rates between 60 and 120 FPS depending on the game, not taking frame generation into account. Older games are usually not a problem at all even at max settings as you’d expect, but reaching a stable 240 FPS is still rare even in older titles.

Game support (or lack thereof)

I’ve played a lot of games (even finished some of them) on this monitor, and I’ve seen a wide variety of implementations and levels of support for the 32:9 aspect ratio. I’d say overall most games released in the past five or so years support ultrawide resolutions to at least some extent, and most recent AAA releases I’ve played actually support it quite well. Anything older than 5 years often requires at least a bit of tinkering to get working, and going further back to games from early 2000s, chances are even mods can’t help you. But there are many exceptions, both good and bad, so it’s hard to say if a specific game will work or not without checking. For that, PCGamingWiki is an invaluable resource, since the articles often list the required configuration changes and mods needed to get ultrawide support working.

Before we get into specific examples, let’s define what I mean by “support”. On a basic level, I consider a game to support 32:9 if I can start it in fullscreen mode at the monitor’s native resolution, and the game has no obvious graphical, interface or gameplay issues caused by the aspect ratio. The goal is that the game looks the way the developer intended it to look, even if that means black bars on the sides. It’s unreasonable to expect every game to have special handling for non-standard aspect ratios, and there are many good technical, artistic and gameplay-related reasons why a developer might choose to only support one or a few aspect ratios — for example, imagine a 2D game where every scene is hand-drawn and carefully composed.

Going further than that, it would be nice if the game actually makes use of the additional horizontal space and shows something instead of just black bars. Expand first and third person views to cover the entire screen, show more of the map in a strategy game, that kind of thing. Every first- and third-person game should have field of view (FOV) settings just for the sake of accessibility if nothing else, but it’s especially important with ultrawide monitors.

Being able to customize the UI / HUD size and layout is also very important for a good experience on an ultrawide. Most games tend to have very important information (health, ammo, minimap) in the corners of the screen, which is fine when the entire monitor is in the center of your vision, but with a monitor over a meter wide you physically can’t see all of the information at once without turning your head. Being able to either limit the width of the UI to a 16:9 or 21:9 area is great, full UI customization where you can position every element individually is even better (and almost unheard of).

First and third person games: mostly great

Most mainstream games use either a first- or third-person perspective, and both types of games do work quite well with a super ultrawide aspect ratio, with some caveats. Most modern AA and AAA games tend to have built-in support for ultrawide resolutions (21:9 and / or 32:9), and FOV settings have become fairly common even in console ports.

It’s not limited to just modern games. For example, Half-Life 2 works almost perfectly well at 32:9 with no tinkering, and it even supports adjusting the HUD size separately to limit it to a 16:9 area. Now, granted, Half-Life 2 has been updated near continuously since its release in 2004, but still, it’s impressive. There are some minor issues: loading screens are stretched, and the first person camera has some clipping issues around the edges of the screen when walking close to walls. Same applies to every Source 1 game I’ve tested.

We’ll talk more about Half-Life 2 later.

Here are some screenshots from other games I’ve played in 32:9 that I managed to find from my collection:

Some notable games I don’t have (presentable) screenshots of but want to mention:

- Batman: Arkham City worked surprisingly really well, despite its age.

- Forza Horizon 5 looks excellent at this aspect ratio, and it also supports forcing the UI to be in 16:9. I still prefer 4, though.

- Titanfall 2 was great — at least in multiplayer — despite it predating the existence of super ultrawide monitors by at least a year. The only issue I noticed was that some non-critical UI elements had stretching and positioning issues. Titanfall 2 is actually a Source 1 game in disguise, so it’s not a huge surprise it worked well.

- Just Cause 2 and 3 worked quite well, but both had their own quirks. JC2 has no problems with the resolution, but it has to be artificially limited to 60 FPS to avoid game-breaking physics issues. JC3 supports arbitrary frame rates and the UI scales quite nicely to 32:9. Well, visually. For some reason the mouse only works properly in menus when playing in 16:9. Even though the UI is scaled and the cursor can be moved anywhere on the screen, the visual cursor is detached from the actual cursor position, making menu navigation (especially the map) a pain.

- Red Dead Redemption 2 has mostly excellent ultrawide support. Most of my time was on the 21:9 monitor, and I can’t remember if I ever tested it at 32:9, but I would assume it works just as well. I have only one gripe: the game’s numerous cutscenes are designed to be in 21:9, even on consoles, so you’d imagine that the cutscenes are even better suited for a native 21:9 or wider display. However, when playing at 21:9 RDR2 adds black bars on all sides of the screen during cutscenes, resulting in a relatively small viewport. First it adds pillarboxing to convert 21:9 into 16:9, and then letterboxes that 16:9 back into 21:9. Sure it works, but it feels like a missed opportunity.

- The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild… wait, what? Yeah, the Cemu Wii U emulator doesn’t just run BOTW with significantly better graphics and performance than either the Wii U or Switch versions, but it can also be configured to run at different aspect ratios, including 32:9. I played through a good chunk of the game this way, and it’s a huge improvement over the original. Unlocking the 30 FPS cap is an even bigger upgrade, and it breaks only some of the physics-based puzzles.

The main caveat with these kinds of games is that the increased field of view comes with unavoidable perspective distortion. While I think most would agree that the screenshots above look good at a glance, if you look at the left and right edges of the screen everything looks stretched out and just a bit weird. This is such an important issue that I have an entire sub-section about it coming later in this post. But let’s tackle all the other types of games first.

Bird’s eye, top-down and isometric games: sometimes actual gameplay benefits!

In terms of gameplay hours, strategy, RPG and tycoon / management games make up a good chunk if not the majority of my gaming time. Think Civilization, Crusader Kings, Factorio, Cities: Skylines, Age of Empires, Baldur’s Gate, Anno and so on.

The primary benefit in these games is that with a wider screen you can actually see more of the game world at once. Isometric games — and by that I mean games that actually use an isometric or similar parallel projection, not just a tilted 3D camera — do not suffer from perspective distortion regardless of aspect ratio (because there’s literally no perspective). Game design-wise showing more of the world is rarely a problem, as most strategy games rarely limit your actual visibility — they use fog of war and other mechanics to limit what you can see and interact with.

But there’s always a catch.

Most of these games are very heavy on UI; a large share if not the majority of the interaction happens via menus, windows and panels, rather than the representation of the game world itself. Therefore, how well the UI adapts to 32:9 is often the primary factor determining if the game is improved or ruined by the added screen real estate. There are two primary approaches: let the UI spread out to make use of all the available space, or limit the UI to around the center of screen so that important information and controls are always visible and easily accessible.

In slow-paced, either turn-based or real-time-with-pause games, I think more screen real estate is always better. In a typical session of Stellaris, Crusader Kings III or Victoria 3 the screen is usually mostly covered by event windows, statistics and other UI thingies, and having more space to wrangle all that information is a welcome improvement. Similarly, Baldur’s Gate 3 and Warhammer 40,000: Rogue Trader — both fairly heavy CRPGs — benefit from the extra space. Rogue Trader is actually the only game I’ve seen to date that customizes its UI layout specifically for ultrawide. I don’t have any screenshots of this, but as one example the level-up UI is split into multiple sections you can’t see at once on a 16:9 display, but on 32:9 everything fits nicely side by side.

But in faster real-time strategy games, a wider UI is rarely a good thing. If the UI is just spread to cover the entire screen, not only is information harder to see at a glance, but the on-screen controls are physically further away from each other, making the game harder to play — unless you aren’t a filthy casual like myself and remember all the hotkeys by heart. This is unfortunately the case in both Age of Empires II: Definitive Edition and Age of Empires IV. I find AoE2 to be still playable at 32:9, but AoE4 is one of the only games I’ve intentionally set to run at 16:9, even though it supports 32:9 perfectly fine from a technical standpoint.

Side scrollers and other games: wild west

The games that don’t fit into either of the above categories are a mixed bunch, but in general they don’t benefit much from the wider aspect ratio, with once again a few exceptions. Many games allow selecting a 32:9 resolution, but don’t benefit from it in any meaningful way. This is not a bad thing as I’ve argued before; if the game is designed to be played at a specific aspect ratio, there is usually a good reason for it.

Some games support 32:9 even though they probably shouldn’t. I’ve played through most of Trine 5 at 32:9, and while the game looks great and is perfectly playable, the wider aspect ratio spoils some secrets and breaks the illusion of tightly designed levels just by showing too much of the environment at once. The same applies to cutscenes: the game made the brave choice not to force a specific aspect ratio during cinematics, so while they are sometimes enhanced by the wider aspect ratio, the reality is that they were only designed for 16:9. Characters stop being animated the moment they exit the 16:9 area in the center, and the “sets” often look incomplete and poorly framed when viewed at wider aspect ratios.

One example of a game that actually benefits from 32:9 is good old Terraria. As a procedurally generated 2D sandbox game, it does not rely on tightly framed levels unlike most other side scrollers. A wider screen shows more of the world, which is beneficial for both exploration and boss battles.

Some assembly required

New games generally support ultrawide aspect ratios better than old games, but there are exceptions in both directions. I think most new games support ultrawide resolutions because there is some market demand for it nowadays and studios explicitly built support for it, while some older games (especially from the early 2000s) might “accidentally” support it, because monitors were less standardized back then and games had to adapt to whatever display the user had.

With the right mods and config changes almost every game can be made to run at 32:9.

I played through F.E.A.R. (from 2005), and after some settings tweaks and fan patches recommended by PCGamingWiki, it was perfectly playable at 32:9 with very few issues. If I recall correctly, the only issue was that fullscreen flashes / JPEG jumpscares didn’t cover the whole screen, leaving black bars on the sides.

Notable newish games I’ve played with poor but fixable ultrawide support include Starfield, and the Resident Evil 2 and 4 remakes.

Starfield was demoed at 32:9 before launch in a weird cross-promotion with Tempur, the makers of very expensive plastic mattresses. However, the final game only shipped with 16:9 and 21:9 support, though this being a Bethesda game, you could mod it to run at 32:9 since day one (which I did). However, both 32:9 and even the officially supported 21:9 had major issues: no FOV slider, weirdly sized weapon models, and the mouse cursor’s visual position not matching its actual position in the ship builder & map menus. They finally added official 32:9 support and fixed some if not all of these issues in a patch four months later, when most people (including myself) had already moved on long ago. The menus are limited to 16:9 to this day, which I don’t think is that big of a problem, but if it bothers you there’s a mod for that as well.

Bethesda released official updates that added ultrawide support for both Skyrim and Fallout 4 some time before Starfield got the ultrawide patch, but the implementations were, in a word, dogshit. Skyrim’s UIs were just stretched to cover the entire screen, with predictably terrible results. In Fallout 4, the UI became a mix of scaled and stretched elements, with unintended cropping and overlapping elements. I’m not usually one to call game developers lazy, but what other explanation could there be for this mess? It seems like no one even started the game once after implementing the “ultrawide support”. Adding insult to injury, in both cases, the updates broke existing mods that actually improved ultrawide support, at least temporarily. To be clear, I blame the entire team and / or management for shipping such half-baked non-solutions, not the individuals who were assigned a ticket with no time or resources to do it properly.

I’ve finished Fallout 3 and New Vegas at 32:9 and 21:9, respectively, and played a couple dozen hours of Skyrim at 32:9 as well. All three were extensively modded, though ultrawide support didn’t require much on top of standard bugfix and quality-of-life mods. The biggest issue with New Vegas was scoped weapons and binoculars, which are implemented using fullscreen overlay textures that were designed exclusively for 16:9 — luckily, replacement mods were easy to come by.

Regarding the Resident Evil remakes, to be honest, I didn’t have high expectations. Traditionally, PC versions of Japanese games have ranged from completely broken to below average at best, but things have definitely improved in the past decade or so. If I recall correctly, both games allowed me to pick 5120x1440 in the settings menu, which already made them better than Starfield at launch. The main issue in both games — shared with more or less every other game made with the RE Engine — is that the camera field of view doesn’t take the aspect ratio into account, resulting in an unplayably zoomed-in view at 32:9. Luckily PCGamingWiki pointed me to download REFramework, which includes ultrawide fixes for both games, including proper FOV settings. Resident Evil 4 does actually have a built-in FOV slider, but the range is so small that the difference between minimum and maximum FOV at 32:9 was almost unnoticeable.

After applying the necessary fixes it was mostly smooth sailing, and I finished RE2 and got pretty far into RE4 without gamebreaking issues. The only notable problem I remember having was that changing the FOV causes worldspace UI elements (like button prompts) to be mispositioned or sometimes even completely missing.

The distortion problem

But as previously teased, 32:9 comes with a major tradeoff compared to normal widescreen: distortion.

The inherent challenge with the first-person perspective (well, all 3D cameras, really) is that while humans have a pretty wide horizontal field of view — about 200 degrees on average — a screen in front of you only occupies a small fraction of that field of view. It depends on screen size, viewing distance and curvature, but for a typical 27-inch widescreen monitor the figure is somewhere between 40 and 60 degrees (calculated using this online tool), and for a TV across the room it can be even less.

However, if you actually try to play an FPS game with a 45-degree horizontal FOV, you have practically no peripheral vision, which besides making you see very little of the game world can also cause motion sickness. As a result, games tend to use much higher FOV values, typically between 80 and 110 on PC, depending on the game and personal preference. Stuffing 110 degrees’ worth of… stuff into a 16:9 rectangle occupying about 50 degrees of actual vision is bound to cause distortion; it’s mathematically impossible to avoid. But that distortion is almost always an acceptable tradeoff, and I don’t think most people even consciously notice it.

Now, you’d expect that an ultrawide monitor (such as this one) would be a perfect fit for high FOV gaming. The natural FOV of a curved 49-inch 32:9 monitor is between 90 and 100 degrees, depending on viewing distance, which is right in the sweet spot for most FPS games. That should result in minimal distortion, right?

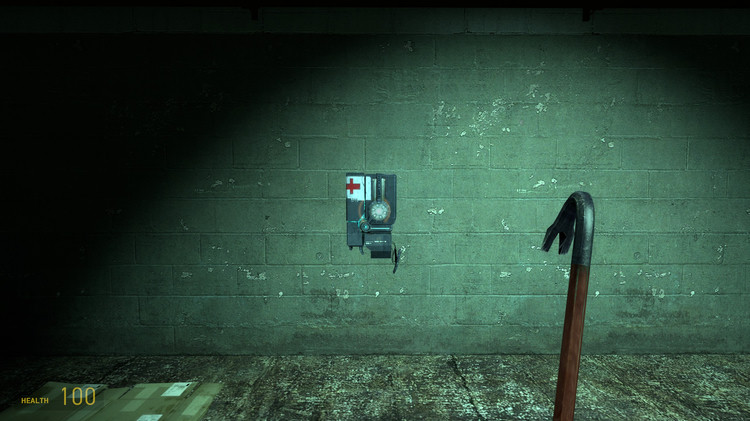

Unfortunately, it’s actually the opposite. Let’s bring back my lovely assistant Half-Life 2 to demonstrate the issue:

When I look at the health charger head-on, it looks as perfectly normal as a piece of dystopian sci-fi medical equipment can look. However, as I turn the camera to look at it from an angle (only turning, not moving at all), the health charger grows multiple times bigger, taking almost one-third of the entire screen at its most extreme.

Unfortunately, this isn’t a problem unique to Half-Life 2; it’s an inherent issue with how rasterization-based 3D rendering works.

In the real world, the usual way to capture a wide field of view onto a rectangular medium is to use a wide-angle or fisheye lens, resulting in barrel distortion. The image is distorted through the entire frame, but objects mostly retain their relative proportions, even near the edges where distortion is strongest. The downside is that straight lines appear curved. Most video games, meanwhile, use rectilinear projection, which preserves the straightness of lines, but distorts the sizes of objects as previously demonstrated. Here’s a pair of images illustrating the difference:

Neither projection is necessarily better than the other — extreme barrel distortion probably makes some people very motion sick, and curved lines can make it hard to judge distances and shapes of objects — but it would be nice to have the option to choose which one to use, especially on an ultrawide monitor. Sadly, video games are almost exclusively limited to rectilinear projection due to how 3D graphics rendering works. Graphics cards are designed to render triangles consisting of straight lines, and rendering curved lines requires tessellating shapes into many more triangles, which is computationally expensive and can lead to other artifacts.

There are post-processing shaders that can reduce the distortion caused by rectilinear projection, such as Panini projection — probably named after the grilled cheese sandwich — which is supported out of the box by Unreal Engine 4 and 5. It comes with its own set of tradeoffs, such as cropping and blurriness caused by the fact it’s a post-process effect warping already rendered images. Despite the popularity of Unreal there are very few games that actually make use of Panini projection; the only non-driving game I’m aware of is the Silent Hill 2 remake.

Half-Life 2 has an FOV slider (and associated console command), which supports values between 75 and 110 degrees. However, while doing some experiments I noticed that it doesn’t actually work the way I thought it did. To figure out what’s going on I ended up reading through some of the publicly available Source engine code to find how the FOV value is handled; the main bits are here and here. I converted the relevant C++ code into an interactive web tool with Gemini 3 Pro, so I could play around with different aspect ratios and FOV values.

HL2 was created in an era where 4:3 and 5:4 monitors were still the norm, but Valve was aware that widescreen monitors were becoming more common. In the Source 1 engine powering the game, FOV values are always relative to 4:3. What this means in practice is that if you set the FOV to 90 degrees, the camera actually uses a 90-degree FOV only when the aspect ratio is 4:3. Increase the aspect ratio to the standard widescreen 16:9, and the effective horizontal FOV becomes about 106 degrees, and at 32:9, the FOV is almost 139 degrees! Even the minimum FOV setting of 75 degrees becomes almost 128 at 32:9.

For context, due to the way projection matrices work the maximum FOV from a single viewpoint is 180 degrees (at least the way games implement it), and the distortion starts becoming gradually yet exponentially worse after about 120 degrees.

Technically speaking, the FOV slider effectively controls the vertical FOV, even though the number it shows is in degrees of horizontal FOV (at 4:3). A wider screen shows more horizontal content at the same vertical FOV. This is a good thing, actually, because it means that players using wider monitors automatically get a reasonable FOV without needing to fiddle with settings. This is known as Hor+ scaling, and most modern games use it, though probably not with 4:3 as the baseline. Its evil double is Vert− scaling, where the horizontal FOV is fixed and widening the aspect ratio reduces the vertical FOV, resulting in a very zoomed-in and often nauseating experience. That’s actually what Resident Evil 4 remake did without mods.

One more factor making the distortion even worse is the fact that ultrawide monitors are often curved, but very few games take advantage of that. Some hardcore racing sims, most notably iRacing, have settings for handling curved ultrawide monitors, where you provide the curvature, size, and viewing distance of the monitor, and the game applies corrections to compensate for it. But unfortunately most games simply treat the display as a flat rectangle, resulting in even more extreme distortion at the edges of the screen.

Speaking of iRacing, it has a feature called “Render scene using 3 projections” designed specifically for 3-monitor setups, but it also supports super ultrawide monitors. As the name implies, it works by rendering the scene from three slightly different viewpoints and then stitches them together, reducing distortion at the edges. This should result in something much better than what can be achieved with post-processing effects. It comes with obvious performance costs as the scene is rendered three times, but graphics API extensions like Vulkan’s VK_KHR_multiview can probably be used to reduce the overhead. This is effectively what games with triple-monitor support have done for years (often in conjunction with Nvidia Surround or AMD Eyefinity), but it would be nice to get the same kind of support for ultrawide monitors in more games.

Graphics hardware and APIs have supported a feature called variable-rate shading (VRS) for a while now, which allows applications to control the shading rate on a per-region basis. As Microsoft’s documentation puts it, it’s like the opposite of multi-sample antialiasing. It was touted as one of the big features of the current console generation, but I haven’t seen it used much in mainstream games. The only example I can remember was the Dead Space remake, where it caused so many artifacts that EA released a patch soon after launch that disabled it on PC by default, and just completely removed it from the console versions.

Where VRS has found some success is in VR games, where headsets capable of eye-tracking can use foveated rendering to reduce the rendering quality in peripheral vision, reducing GPU usage without noticeable loss of visual fidelity.

But I wonder if you could also apply VRS to optimize gaming on super ultrawide monitors. Since a large share of the viewport is heavily distorted, maybe you could get away with rendering those areas at a lower quality without the user noticing? I don’t think anyone has tried this yet, but it could be an interesting experiment.

Multitasking while gaming

I am one of those weird people who somewhat unashamedly consume multiple forms of media simultaneously. I don’t watch Family Guy compilations while playing Disco Elysium, or listen to an audiobook while playing Call of Duty, but I do often consume podcasts and long-form video content while playing simpler and / or less intense games. Catching up on gaming podcasts while playing a few (hundred) turns of Civilization, chopping down trees (or demons) in Old School RuneScape during my annual re-watch of the Folding Ideas filmography, slowly filling sudoku puzzles while watching a three-hour video essay about the Alan Wake franchise — those kinds of things. I just need something to keep my hands busy while I focus on listening or watching. Sometimes it’s just a really grindy game, and I want some background noise to keep me sane.

With two or more monitors, this crime against art is easy to commit: put the game on one screen, and the video or podcast on the other.

Unfortunately, a single humongous monitor isn’t ideal for that kind of multitasking. Games are largely designed to be run in fullscreen, but if I do that, well, obviously I can’t use the monitor for anything else. Almost every game includes a windowed mode nowadays, but it’s surprising how rare it is to find games that actually have a resizable window in windowed mode; most games have a set of predefined resolutions to pick from, and none of them are optimal for 1440 pixels of vertical space. The window title and borders also eat a bit of space, and if I select a borderless windowed mode, I can’t move the game window where I want it.

I can’t use fullscreen for videos either, so most of the time I have to look at YouTube’s ugly UI as a further distraction, while not making good use of the full height of the monitor. Sometimes, very rarely, I’ll bother to futz around with Firefox’s picture-in-picture mode to get a mostly clean viewing experience.

This particular monitor does have the picture-by-picture feature, which can kind of solve this problem, but it comes with so many compromises to the gaming features that I haven’t used it since the first week.

Now, if I also were the kind of person who regularly posts on LinkedIn, I would probably say something like

Getting this monitor made me realize that both games and other media deserve my full attention; splitting my focus between them is a disservice to both media and myself. I now see the error of my ways. I now enjoy games more than ever before, I retain much more information from podcasts and video essays, and I feel more present in my daily life.

Also, somehow this experience taught me several valuable lessons about content marketing and B2B sales.

But that would be a lie. The actual end result is that I still multitask a lot of the time, but both the game and the other content look and feel worse than they would on separate monitors. Picture watching a documentary in the leftmost third of the screen while playing Stellaris in a relatively small 1920x1080 window next to it, because the game (like every other game from Paradox Development Studio) doesn’t support resizable windows. Most of the screen is just wasted space. Not exactly a premium experience.

Gaming summary

A super ultrawide monitor can provide breathtaking gaming experiences for certain types of games — playing Alan Wake 2 on this monitor with path tracing enabled in a darkened room is one of the best visual experiences I’ve ever had with any entertainment medium. FPS games are more immersive, strategy and management games might be easier to play, and if you are into simulators, it’s at least better than a single widescreen display.

However, a lot of the time, reaching that experience doesn’t come for free, and I’m not just talking about the price of the monitor itself. While 32:9 support has become more common and better implemented in recent years, you have to be prepared for the fact that many games require tweaks, mods, and workarounds to run properly at this aspect ratio, if at all. You can’t just install any game from Steam, max out the settings, and expect it to work flawlessly — unless you are willing to drop down to 16:9 and waste 50% of your screen.

The near-universal distortion issue is also something that can’t be ignored. While a large 32:9 monitor makes games more immersive, the fact of the matter is that the extra field of view is mostly decorative rather than functional. You can see a bit more of the game world, sure, but due to heavy distortion it doesn’t significantly increase your situational awareness like a VR headset or a triple-monitor setup would. It can still be very impressive, but for me it’s more of a luxury feature than a fundamental improvement to gameplay.

It’s a monitor and / or aspect ratio for enthusiasts, for people who treat gaming as a hobby rather than just a form of entertainment. Like owning a sports car or a fancy Japanese chef’s knife, it’s not for everyone, and you have to be willing to put in some effort to get the most out of it. I’m not being elitist here; if you are not willing to download and install random DLL mods and browse through Reddit threads to find potential fixes for ultrawide-related issues, you will be disappointed. Just get a fancy 16:9 monitor instead, or if you’re a bit more adventurous, a 21:9 ultrawide is a much safer bet.

Other random thoughts and observations that didn’t fit anywhere else

One of the primary challenges of using a 32:9 monitor is, well, the aspect ratio. It has a surprisingly big impact on various things one might do on a computer. We’ve covered productivity and gaming so far, but there are many things that don’t fit neatly into either category.

For example, screenshots. Fullscreen screenshots at 32:9 look weird when shared elsewhere, as you might have seen from the examples in this very article. They are awkward enough for most other desktop users, but they are especially bad on mobile devices. Many platforms also limit image size and / or perform automatic resizing (and compression), often resulting in tiny, unreadable images. Enabling HDR causes its own set of problems for screenshots, but that’s a topic for another day.

Screen sharing, recording, and streaming also become more awkward, for many of the same reasons.

If I share my entire screen to show something to a coworker, the text will be unreadably small for them, or they have to constantly pan and zoom to see the thing I’m trying to show. Same thing applies to casually streaming a game to friends on Discord or Twitch.

YouTube does technically support 32:9 videos, but no one is going to watch those except to test and demo a new monitor. If you want to share gameplay clips or create something more elaborate, you either have to play in 16:9, or crop the footage in a video editor. At least OBS, Nvidia ShadowPlay, and Steam’s new video recording feature all work fine at 32:9, so capturing footage isn’t a problem. I did find several bugs in DaVinci Resolve when trying to edit 32:9 footage, though.

Streaming to a larger audience is its own can of worms. Twitch does technically support 21:9, but once again, no one is going to watch an ultrawide stream — at the time of writing, the top stream tagged with Ultrawide has 74 viewers. So you’ll have to either run the game (or other application) at 16:9, or maybe run it at 21:9 and arrange it in OBS alongside other elements to fill a 16:9 frame. Speaking of OBS and other elements, you probably want to see your streaming software and chat windows while streaming, but if you’re playing a game in fullscreen, you can’t. Borderless windowed mode could potentially work, provided that you can move the game window where you want it, which is a bit of a challenge since windows are usually moved by dragging the title bar / borders, which, by definition, are not visible in borderless mode. This is the kind of scenario the picture-by-picture feature was intended for, but as mentioned before, the implementation on this particular monitor isn’t very good for gaming.

Summary

This is the kind of monitor one might think of when imagining the ultimate productivity and gaming setup, with zero compromises. Ironically enough, using it can require making many more compromises than with a more conventional display.

The hardware is mostly excellent from a specification and performance standpoint, but choices that have been made either out of incompetence or cost-cutting result in an overall compromised experience. Firmware bugs, weirdly placed ports and dead / stuck pixels should have no place in a supposed top-tier product. I love it, I hate it.

From a productivity standpoint, a single 32:9 panel offers more flexibility than a dual-monitor setup, but you will spend more time fiddling with window arrangements than you would with two regular monitors. Slightly higher pixel density and better tools for window management would go a long way.

If you primarily play the latest and most popular games by big (mostly Western) and / or PC-focused studios, you will likely have a great experience gaming at 32:9. Fortnite, Call of Duty, Battlefield, Minecraft, Terraria, Factorio — they all work great. Play anything else, and be prepared to get your hands dirty with mods and config tweaks to get things working properly. Perfection is often unattainable, and even the games with great ultrawide support suffer from distortion issues inherent to the way 3D graphics are rendered. Some games just can’t be played at 32:9 at all, often for good reasons. If you are considering getting into PC gaming for the first time, resist the urge to start with an ultrawide monitor. You’ll thank me later.

Regardless, I’m looking forward to the next 1,000 days with this monitor — provided it doesn’t die on me first like the last one.

If you managed to read this far, I’m amazed. The scope of this article ballooned way out of control, as it always does with me. This is actually my third attempt at writing a review of the Samsung Odyssey Neo G9. I started the first draft the week it arrived, but I gave up when I noticed I had written several thousand words about monitors I had used in the past, without ever getting to the actual review. I started the second draft a year later (titled “A year in 32:9”), but it suffered from the same problem, plus it also ballooned into a game compatibility database, rather than a coherent article. On the plus side, both of those drafts were useful for this third and final version, which took me almost a month of on-and-off writing to finish. I could never be a journalist.

You can follow me on Bluesky, and this blog should also have a functional Atom feed if someone is still using that technology in 2025.