Eh! All of you, come here! Taste it! Taste it! Taste it! Taste it!

Gordon Ramsay

If you want to cook a great dish, you’ve got to taste it every step of the way. Taste the ingredients you buy, the components you prepare, and the spices and seasonings. If you can’t taste it, you smell it, feel it, or listen to it. And then you adjust. Taste and adjust until you create a dish you like.

“Taste and adjust” is a form of continuous improvement applied to the creation of food. The hallmark methodologies of the scientific method, Kaizen, TPS, PDCA, TDD, design sprints, or extreme programming, that have led to some of humanity’s best creations, are all forms of continuous improvement. At their core is this principle:

Creators need an immediate connection to what they’re creating.

Bret Victor, Inventing on Principle

Bret Victor says that “working in the head doesn’t scale”, and that understanding comes from seeing data, flow, and state directly. When building products, can you see the data, flow, and state directly? Can you “taste” your product every step to ensure it’s exactly what you and your users want?

The chef’s line-tasting, our flywheel, harness, environment, or feedback loop, is the framework in which we apply this principle to product creation. The product and engineering functions must build and maintain this flywheel together, every step of the way.

The product development flywheel

To build the flywheel, we ask:

- “What is the simplest experiment I can run to validate this hypothesis?”, and then

- “What do I need to run this experiment?”

The machinery that enables running such experiments frequently and quickly is the flywheel.

It could be in the form of an operator’s console that allows product to tweak config on the fly, or building a prototype, or a feature-flag allowing tests with beta-users, or publishing a new metric that removes a blind spot. Even unit tests that verify whether the code does what product intends are part of this flywheel.

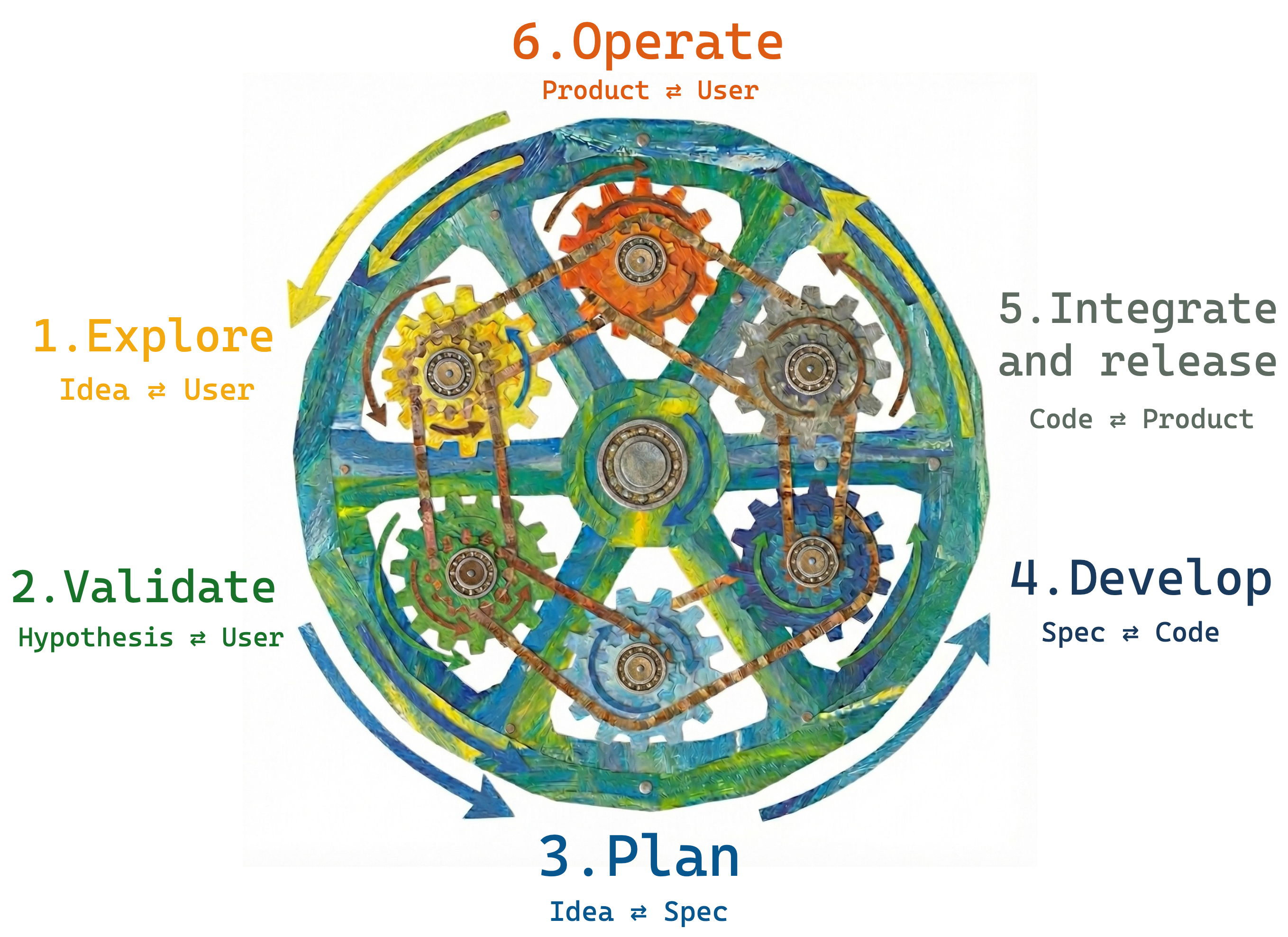

While this seems like a simple enough principle to apply, in reality, we are faced with the inherent complexity of working with many people, roles, and tools. A typical product development lifecycle (PDLC) looks like the abstract machine shown below. Each phase has controls and measurements around specific feedback loops (such as Idea ⇄ User), and the phases are interconnected through reinforcing and balancing information channels.

Here’s a list of some ways to “taste” at each phase, and a healthy level of involvement of product and engineering in each of them.

| Phase | Feedback Loop | Feedback tools (ways to taste, smell, or touch) | Healthy involvement % |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Explore | Idea ⇄ User | Pen + Paper, User Research, Design Sprints, Landing Pages, Campaigns | 90% Product, 10% Engineering |

| 2. Validate | Hypothesis ⇄ User | Wireframes, Prototypes, Proofs of Concept | 70% Product, 30% Engineering |

| 3. Plan | Idea ⇄ Spec | Thin slices of work, Experiments, Spikes, Tracing Bullets | 50% Product, 50% Engineering |

| 4. Develop | Spec ⇄ Code | TDD, Types, Compilation, REPL, AI Assisted Coding | 10% Product, 90% Engineering |

| 5. Integrate and release | Code ⇄ Product | Previews, Devboxes, Staging, Integration, Quality Analysis | 30% Product, 70% Engineering |

| 6. Operate | Product ⇄ User | Product Observability, Operator Consoles, Alerts | 50% Product, 50% Engineering |

Fine-Tuning the Flywheel

- Get end-to-end product builders: You want teams that go together from phase 1 to 6, and then around again, to close the loop on their creation. Look for roles siloed in fewer phases, and work to involve them in all phases.

- Get involved early: Phases 1 and 2 are the ideation phase, and the most important thing to do here is to listen, and understand the problem deeply. I wrote about this earlier in the series. Building this phase of the flywheel for new products is cheap, especially with vibe coding. However, keeping experimentation costs low as the product matures can be challenging. Work to keep experiments cheap by using feature flags, or by maintaining experimental or forked versions of applications.

- Get closer to the user: Phases 3, 4, and 5 make up the typical SDLC (software development lifecycle), and in my experience, engineering is less involved in phases 1, 2 and 6. This is unfortunate because phases 1, 2, and 6 interface with the user and house the most important feedback loops.

- Planning > Speed: Development (phase 4) is arguably the most expensive part of most tech companies. While there’s a lot of focus on making development faster to reduce costs, reducing work through planning (phase 3) is far more effective. Break down problems, find thin slices of work to serve, and prioritise ruthlessly.

- Close outer feedback loops: Phase 6 should close the loop on business goals through product observability, in addition to the local feedback loops of individual features or initiatives.

**Stronger flywheel ⇒ Immediate connection ⇒ Better product**

So, review your flywheel periodically. Lubricate the gears, and tighten the feedback loops. Ultimately, ensure that everyone on the team feels empowered to stop the line, take a spoonful, and say, “Needs more salt.”