Running your own Autonomous System on the public internet sounds like something reserved for ISPs and large enterprises. It’s not. With sponsoring LIRs making AS numbers and IPv6 prefixes accessible to individuals, and FreeBSD providing the routing tools to make it work, you can announce your own address space to the Default-Free Zone from a single virtual machine.

This article walks through the complete setup: obtaining resources from RIPE via a sponsoring LIR, configuring a FreeBSD BGP router with FRR, building GRE/GIF tunnels to distribute prefixes to remote servers, and solving the routing challenge that arises when a server needs to speak from two different IPv6 address spaces simultaneously.

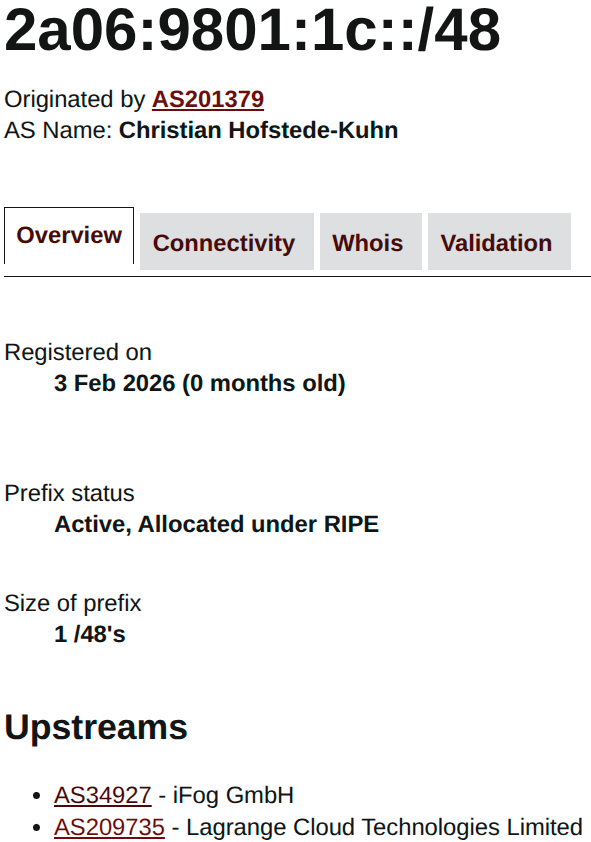

Note on addresses: All provider-assigned IP addresses, hostnames, and management IPs in this article have been replaced with RFC 5737 / RFC 3849 documentation ranges. My own AS number (AS201379) and prefix (2a06:9801:1c::/48) are public BGP resources and shown as-is. The upstream AS numbers (AS34927, AS209735) are equally visible in public routing tables.

Why Run Your Own AS?

Provider-assigned IPv6 addresses are tied to that provider. Move to a different hoster and your addresses change - along with DNS records, firewall rules, reputation, and every system that references them. With your own AS and prefix, your addresses follow you. Migrate a server, update a tunnel endpoint, and traffic flows again without touching a single service configuration.

There are also less practical reasons. Understanding BGP transforms how you think about internet routing. Watching your prefix propagate through the DFZ and appear on looking glasses worldwide is genuinely satisfying. And if you run services across multiple providers, having provider-independent addressing simplifies the architecture considerably.

Obtaining Resources

To announce prefixes on the internet, you need two things from a Regional Internet Registry (in Europe, that’s RIPE NCC):

- An AS number - your identity in BGP. Mine is AS201379.

- An IPv6 prefix - the address space you’ll announce. I received 2a06:9801:1c::/48.

As an individual, you don’t need to become a RIPE member (which involves fees and bureaucracy). Instead, you work with a sponsoring LIR - an existing RIPE member who sponsors your resource registration. Several LIRs cater to hobbyists and small operators. The process typically involves:

- Filling out a request form with your intended use case

- Creating the appropriate RIPE database objects (aut-num, inet6num, route6)

- Setting up RPKI ROAs (Route Origin Authorizations) to cryptographically bind your prefix to your AS

Once the paperwork is done, you need upstream connectivity - someone willing to carry your BGP sessions and announce your routes to the rest of the internet.

Architecture Overview

The setup involves two tiers: a BGP router that peers with upstream providers, and downstream servers that receive tunneled subnets from the router’s /48.

┌──────────────────────────────┐

│ Default-Free Zone │

└──────┬──────────────┬─────────┘

│ │

AS34927 (iFog) AS209735 (Lagrange)

│ │

GRE tunnel Direct peering

│ │

┌──────┴──────────────┴─────────┐

│ router01 (BGP Router) │

│ FreeBSD + FRR │

│ AS201379 │

│ 2a06:9801:1c::/48 │

└──────┬──────────────┬─────────┘

│ │

GIF tunnel GIF tunnel

(proto 41) (proto 41)

│ │

┌──────┴───┐ ┌──────┴──────────┐

│ vps01 │ │ dcgw01 │

│ VPS │ │ DC OPNsense │

│ :1000:: │ │ :2000::/62 │

│ /64 │ │ │

└──────────┘ └──────────────────┘

The BGP router (router01) announces 2a06:9801:1c::/48 to two upstream providers and maintains a blackhole route for the aggregate. Individual /64s (and a /62 for my Colocation datacenter) are tunneled to downstream servers via GIF tunnels (IPv6-in-IPv4 encapsulation). Each server receives real, globally routable addresses from my prefix while keeping its existing provider-assigned IPv6 fully operational.

The BGP Router

The router runs on a FreeBSD VM at a colocation facility with direct connectivity to two upstream networks. Let’s walk through each layer.

Network Configuration

The router’s /etc/rc.conf sets up the physical interface, tunnel interfaces, and static routes:

hostname="router01"

# Security

kern_securelevel_enable="YES"

kern_securelevel="2"

# Physical interface

ifconfig_vtnet0="inet 198.51.100.10/24 -rxcsum -txcsum -rxcsum6 -txcsum6 -lro -tso"

ifconfig_vtnet0_ipv6="inet6 2001:db8:100::96/64"

defaultrouter="198.51.100.1"

ipv6_defaultrouter="2001:db8:100::1"

# Loopback alias for originated prefix

ifconfig_lo0_alias0="inet6 2a06:9801:1c::1 prefixlen 64"

# Tunnel interfaces

cloned_interfaces="gif0 gif1 gre0"

kld_list="if_gif if_gre"

# GRE Tunnel to transit provider (iFog)

ifconfig_gre0="tunnel 198.51.100.10 198.51.100.44"

ifconfig_gre0_ipv6="inet6 2001:db8:300::2 2001:db8:300::1 prefixlen 128"

ifconfig_gre0_descr="Transit-iFog"

# GIF Tunnel to VPS (vps01)

ifconfig_gif0="tunnel 198.51.100.10 203.0.113.10"

ifconfig_gif0_ipv6="inet6 2a06:9801:1c:ffff::1 2a06:9801:1c:ffff::2 prefixlen 128"

ifconfig_gif0_descr="Tunnel-to-VPS"

ipv6_route_cloud="2a06:9801:1c:1000::/64 2a06:9801:1c:ffff::2"

# GIF Tunnel to datacenter firewall (dcgw01)

ifconfig_gif1="tunnel 198.51.100.10 192.0.2.50"

ifconfig_gif1_ipv6="inet6 2a06:9801:1c:ffff::3 2a06:9801:1c:ffff::4 prefixlen 128"

ifconfig_gif1_descr="Tunnel-to-Datacenter"

ipv6_route_dc="2a06:9801:1c:2000::/62 2a06:9801:1c:ffff::4"

# Blackhole route for the aggregate + downstream routes

ipv6_static_routes="myblock cloud dc"

ipv6_route_myblock="2a06:9801:1c::/48 -reject"

ipv6_gateway_enable="YES"

# Services

pf_enable="YES"

pflog_enable="YES"

frr_enable="YES"

zfs_enable="YES"

sshd_enable="YES"

A few things worth explaining:

- The blackhole route (

-rejectfor the /48) is essential. Without it, traffic for unassigned subnets within your prefix would follow the default route back to the upstream, creating a routing loop. The blackhole ensures unrouted traffic is dropped locally. - Point-to-point tunnel addresses use /128 prefixes on the

2a06:9801:1c:ffff::/64link subnet. Each tunnel gets a pair of addresses from this range. - Downstream routes point specific subnets at the far end of each tunnel. The /64 for the VPS and /62 for the datacenter are routed to their respective tunnel endpoints.

- GRE vs GIF: The iFog peering uses GRE because that’s what the provider requires. The downstream tunnels use GIF (protocol 41, IPv6-in-IPv4) which is simpler and has less overhead.

FRR Configuration

FRR (Free Range Routing) handles the BGP sessions. The configuration lives at /usr/local/etc/frr/frr.conf:

frr version 10.5.1

frr defaults traditional

hostname router01

log syslog informational

service integrated-vtysh-config

!

ipv6 prefix-list PL-MY-NET seq 5 permit 2a06:9801:1c::/48

!

ipv6 prefix-list PL-BOGONS seq 5 deny ::/0 le 7

ipv6 prefix-list PL-BOGONS seq 10 deny ::/8

ipv6 prefix-list PL-BOGONS seq 15 deny 100::/8

ipv6 prefix-list PL-BOGONS seq 20 deny 200::/7

ipv6 prefix-list PL-BOGONS seq 25 deny 400::/6

ipv6 prefix-list PL-BOGONS seq 30 deny 800::/5

ipv6 prefix-list PL-BOGONS seq 35 deny 1000::/4

ipv6 prefix-list PL-BOGONS seq 40 deny 4000::/3

ipv6 prefix-list PL-BOGONS seq 45 deny 6000::/3

ipv6 prefix-list PL-BOGONS seq 50 deny 8000::/3

ipv6 prefix-list PL-BOGONS seq 55 deny a000::/3

ipv6 prefix-list PL-BOGONS seq 60 deny c000::/3

ipv6 prefix-list PL-BOGONS seq 65 deny e000::/4

ipv6 prefix-list PL-BOGONS seq 70 deny f000::/5

ipv6 prefix-list PL-BOGONS seq 75 deny f800::/6

ipv6 prefix-list PL-BOGONS seq 80 deny fc00::/7

ipv6 prefix-list PL-BOGONS seq 85 deny fe80::/10

ipv6 prefix-list PL-BOGONS seq 90 deny fec0::/10

ipv6 prefix-list PL-BOGONS seq 95 deny ff00::/8

ipv6 prefix-list PL-BOGONS seq 100 deny 2a06:9801:1c::/48

ipv6 prefix-list PL-BOGONS seq 105 deny ::/0 ge 49

ipv6 prefix-list PL-BOGONS seq 110 permit ::/0 le 48

!

route-map RM-IFOG-OUT permit 10

match ipv6 address prefix-list PL-MY-NET

set community 34927:9501 34927:9301 additive

exit

!

route-map RM-LAGRANGE-OUT permit 10

match ipv6 address prefix-list PL-MY-NET

set as-path prepend 201379 201379

exit

!

route-map RM-IFOG-IN permit 10

match ipv6 address prefix-list PL-BOGONS

exit

!

route-map RM-LAGRANGE-IN permit 10

match ipv6 address prefix-list PL-BOGONS

exit

!

ipv6 route 2a06:9801:1c::/48 blackhole

!

router bgp 201379

bgp router-id 198.51.100.10

no bgp default ipv4-unicast

neighbor 2001:db8:300::1 remote-as 34927

neighbor 2001:db8:300::1 description Upstream-iFog

neighbor 2001:db8:300::1 ttl-security hops 1

neighbor 2001:db8:300::1 update-source gre0

neighbor 2001:db8:100::ff remote-as 209735

neighbor 2001:db8:100::ff description Upstream-Lagrange

neighbor 2001:db8:100::ff ttl-security hops 1

neighbor 2001:db8:100::ff update-source 2001:db8:100::96

!

address-family ipv6 unicast

network 2a06:9801:1c::/48

neighbor 2001:db8:300::1 activate

neighbor 2001:db8:300::1 soft-reconfiguration inbound

neighbor 2001:db8:300::1 maximum-prefix 250000 90 restart 30

neighbor 2001:db8:300::1 route-map RM-IFOG-IN in

neighbor 2001:db8:300::1 route-map RM-IFOG-OUT out

neighbor 2001:db8:100::ff activate

neighbor 2001:db8:100::ff soft-reconfiguration inbound

neighbor 2001:db8:100::ff maximum-prefix 250000 90 restart 30

neighbor 2001:db8:100::ff route-map RM-LAGRANGE-IN in

neighbor 2001:db8:100::ff route-map RM-LAGRANGE-OUT out

exit-address-family

exit

There’s a lot happening here. Let me break down the key design decisions.

Prefix Lists

Two prefix lists control what gets sent and received:

- PL-MY-NET: Matches only our /48. Used in outbound route-maps to ensure we only ever announce our own prefix.

- PL-BOGONS: A comprehensive bogon filter for inbound routes. This rejects non-routable address space (link-local, ULA, multicast, documentation ranges), our own prefix (to prevent loops), and anything more specific than a /48 or less specific than a /8. The final

permit ::/0 le 48at the end accepts everything that survived the deny rules.

The bogon filter deserves emphasis. Accepting bad routes from peers can cause anything from black-holed traffic to becoming an unwitting participant in route hijacks. Filter aggressively on inbound.

Route Maps

Each peer gets its own pair of inbound/outbound route maps:

- Outbound to iFog (

RM-IFOG-OUT): Announces our /48 with BGP communities34927:9501and34927:9301. These are iFog-specific communities that control route propagation - in this case, requesting announcement to specific peering partners. - Outbound to Lagrange (

RM-LAGRANGE-OUT): Announces our /48 with AS-path prepending (adds our ASN twice). This makes the Lagrange path appear longer to the rest of the internet, steering inbound traffic to prefer the iFog path. Useful for traffic engineering when one upstream has better connectivity. - Inbound from both: Apply the bogon filter to reject garbage routes.

BGP Session Details

no bgp default ipv4-unicast: We’re IPv6-only. Don’t activate IPv4 address family by default.ttl-security hops 1: GTSM (Generalized TTL Security Mechanism) - reject BGP packets with TTL less than 254. This prevents remote attacks on the BGP session since only directly connected peers can send packets with TTL 255.soft-reconfiguration inbound: Store received routes before applying filters. This lets you change inbound policy without resetting the BGP session.maximum-prefix 250000 90 restart 30: Safety valve. If a peer sends more than 250,000 prefixes (or 90% of that as a warning), tear down the session and retry after 30 minutes. Protects against route leaks from upstream.

Firewall on the Router

The BGP router’s PF configuration protects the control plane while allowing data plane forwarding:

# --- Macros ---

ext_if = "vtnet0"

dc_tun = "gif1"

vps_tun = "gif0"

trusted_ipv4 = "{ 198.51.100.100, 198.51.100.101 }"

trusted_ipv6 = "{ 2001:db8:ffff:1::/64, 2001:db8:ffff:2::/64 }"

bgp_peers_v4 = "{ 198.51.100.20 }"

bgp_peers_v6 = "{ 2001:db8:100::ff }"

ifog_gre_endpoint = "198.51.100.44"

ifog_bgp_peer = "2001:db8:300::1"

my_network_v6 = "2a06:9801:1c::/48"

vps_v4 = "203.0.113.10"

# --- Tables ---

table <bruteforce> persist

table <trusted_v4> const { $trusted_ipv4 }

table <trusted_v6> const { $trusted_ipv6 }

table <bgp_peers_v4> const { $bgp_peers_v4 }

table <bgp_peers_v6> const { $bgp_peers_v6 }

table <bogons> const { 0.0.0.0/8, 10.0.0.0/8, 172.16.0.0/12, \

192.168.0.0/16, 169.254.0.0/16, ::/96, fc00::/7, \

fec0::/10, ff00::/8 }

# --- Options ---

set skip on lo0

set block-policy drop

set loginterface $ext_if

# --- Scrub ---

scrub in all fragment reassemble

scrub on $vps_tun max-mss 1440

scrub on $dc_tun max-mss 1140

scrub on gre0 max-mss 1400

# --- Filtering ---

block log all

block in quick on $ext_if from { <bogons>, $my_network_v6 } to any

antispoof quick for { $ext_if }

# --- Control Plane ---

# SSH from trusted sources only

pass in quick on $ext_if proto tcp from <trusted_v4> to ($ext_if) port 22 \

flags S/SA keep state \

(max-src-conn 5, max-src-conn-rate 3/30, \

overload <bruteforce> flush global)

pass in quick on $ext_if proto tcp from <trusted_v6> to ($ext_if) port 22 \

flags S/SA keep state \

(max-src-conn 5, max-src-conn-rate 3/30, \

overload <bruteforce> flush global)

# BGP (TCP 179) - strictly limited to known peers

pass in quick on $ext_if proto tcp from <bgp_peers_v4> to ($ext_if) port 179 \

flags S/SA keep state

pass in quick on $ext_if proto tcp from <bgp_peers_v6> to ($ext_if) port 179 \

flags S/SA keep state

# GRE tunnel from iFog

pass in quick on $ext_if proto gre from $ifog_gre_endpoint to ($ext_if)

pass in quick on gre0 proto tcp from $ifog_bgp_peer to any port 179

# ICMPv6: essential for NDP, PMTUD, and diagnostics

pass in quick inet6 proto ipv6-icmp icmp6-type { \

echoreq, echorep, neighbrsol, neighbradv, \

toobig, timex, paramprob, routersol }

pass in quick inet proto icmp icmp-type { echoreq, unreach, timex }

# --- Data Plane ---

# Inbound traffic destined for our prefix

pass in quick on $ext_if inet6 from any to $my_network_v6 keep state

pass in quick on gre0 inet6 from any to $my_network_v6 keep state

# Return traffic from downstream tunnels

pass in quick on $vps_tun inet6 from $my_network_v6 to any keep state

pass in quick on $dc_tun inet6 from $my_network_v6 to any keep state

# GIF tunnel encapsulation (proto 41) from downstream endpoints

pass in quick on $ext_if proto 41 from $vps_v4 to ($ext_if)

# Outbound

pass out quick all keep state

The firewall cleanly separates control plane (SSH, BGP sessions) from data plane (forwarded traffic). The control plane rules are strict: BGP is locked to known peer addresses, SSH to trusted management IPs. The data plane rules are simpler since the router just needs to forward packets between upstreams and downstream tunnels.

The block in quick on $ext_if from { <bogons>, $my_network_v6 } rule is important - it drops packets claiming to come from our own prefix arriving on the external interface. If someone on the internet spoofs a source address from our range, this catches it before it enters the forwarding path.

Note the per-tunnel MSS clamping in the scrub section. Each tunnel has different overhead (GRE adds more headers than GIF), so the MSS values differ. Getting this wrong causes mysterious connection stalls with large packets.

The Downstream Server: Dual-Stack with Policy Routing

This is where things get interesting. The VPS (vps01) already has provider-assigned IPv6 from its hoster. Jails on this server use addresses from both address spaces:

- Provider IPv6 (2001:db8:200:0:1000::/68) - the hoster’s addresses, NATed to the host

- BGP IPv6 (2a06:9801:1c:1000::/64) - our own prefix, routed natively via the GIF tunnel

- Private IPv4 (10.254.254.0/24) - NATed to the host’s public IPv4

The challenge: when a jail sends traffic from its BGP address (2a06:…), that traffic must exit through the GIF tunnel to the BGP router - not through the default route to the VPS provider, where it would be dropped as spoofed. But traffic from the provider address must continue using the normal default route.

The solution is dual-FIB policy routing - FreeBSD’s implementation of multiple routing tables.

How Dual-FIB Works

FreeBSD supports multiple routing tables called FIBs (Forwarding Information Bases). Each FIB is an independent routing table with its own default route and entries. Interfaces and PF rules can assign traffic to a specific FIB, and the kernel consults the appropriate table when forwarding.

FIB 0 (default):

default --> vtnet0 --> VPS provider upstream

Used by: host traffic, provider-addressed jail traffic

FIB 1:

default --> gif0 --> BGP router (router01)

Used by: BGP-addressed jail traffic (2a06:9801:1c::/48)

Network Configuration

Here’s the relevant portion of the server’s /etc/rc.conf:

hostname="vps01.example.com"

kern_securelevel_enable="YES"

kern_securelevel="2"

# Primary interface - provider IPv4 and IPv6

ifconfig_vtnet0="inet 203.0.113.10 netmask 255.255.252.0 -lro -tso"

ifconfig_vtnet0_ipv6="inet6 2001:db8:200::2 prefixlen 68"

defaultrouter="203.0.113.1"

ipv6_defaultrouter="fe80::1%vtnet0"

# Jail bridge - three address spaces

cloned_interfaces="bridge0 gif0"

ifconfig_bridge0_name="bastille0"

ifconfig_bastille0="inet 10.254.254.1/24"

ifconfig_bastille0_ipv6="inet6 2001:db8:200:0:1000::1 prefixlen 68"

ifconfig_bastille0_alias0="inet6 2a06:9801:1c:1000::1 prefixlen 64"

# GIF tunnel to BGP router - assigned to FIB 1

ifconfig_gif0="fib 1 tunnel 203.0.113.10 198.51.100.10 tunnelfib 0"

ifconfig_gif0_ipv6="inet6 2a06:9801:1c:ffff::2 2a06:9801:1c:ffff::1 prefixlen 128"

# Enable forwarding

gateway_enable="YES"

ipv6_gateway_enable="YES"

# FIB 1 routing table entries

static_routes="fib1default jailleak bgplink"

route_fib1default="-6 default -interface gif0 -fib 1"

route_jailleak="-6 2001:db8:200:0:1000::/68 -interface bastille0 -fib 1"

route_bgplink="-6 2a06:9801:1c:1000::/64 -interface bastille0 -fib 1"

The GIF tunnel configuration deserves a closer look:

ifconfig_gif0="fib 1 tunnel 203.0.113.10 198.51.100.10 tunnelfib 0"

This single line contains two critical directives:

fib 1: The tunnel interface itself lives in FIB 1. Traffic arriving on gif0 and traffic routed out gif0 consults routing table 1.tunnelfib 0: But the outer IPv4 encapsulation (the 203.0.113.10 —> 198.51.100.10 wrapper) uses FIB 0. This is essential - the IPv4 path to the BGP router goes through the provider’s default route in FIB 0. Withouttunnelfib 0, the encapsulated packets would try to use FIB 1’s default route (which points at gif0 itself), creating a recursive loop.

The three static routes in FIB 1 complete the picture:

fib1default: Default route in FIB 1 exits through gif0 to the BGP routerjailleak: Tells FIB 1 that the provider’s jail subnet is reachable via bastille0 (without this, return traffic in FIB 1 for jails’ provider addresses would try to exit through gif0)bgplink: Same for the BGP jail subnet - FIB 1 needs to know these addresses are local on bastille0

PF: The Routing Glue

PF is where the address-based routing decision happens. When a jail sends a packet from a BGP address, PF assigns it to FIB 1:

# BGP-addressed jail traffic --> force into routing table 1 (exits via gif0)

pass in quick on bastille0 inet6 from $bgp_net to any rtable 1 keep state

The rtable 1 directive is the key. It tells PF to route matching packets using FIB 1 instead of the default FIB 0. Since FIB 1’s default route points out gif0 to the BGP router, these packets get encapsulated and sent to router01, which then forwards them to the internet with the correct source address.

For traffic arriving on the tunnel destined for jails, PF uses reply-to to ensure return traffic takes the same path:

# Inbound BGP traffic - reply-to ensures responses exit via gif0

pass in quick on $tun_if reply-to ($tun_if $bgp_hub_ip) inet6 \

from any to $bgp_net keep state

# BGP ICMPv6 - also needs reply-to for correct return path

pass in quick on $tun_if reply-to ($tun_if $bgp_hub_ip) inet6 proto ipv6-icmp \

from any to $bgp_net \

icmp6-type { echoreq, echorep, toobig, timex, paramprob } \

keep state

Without reply-to, the kernel would consult FIB 0 for return traffic (since the jail itself isn’t in FIB 1), and replies to BGP-addressed connections would exit through vtnet0 with the wrong source routing - getting dropped as spoofed by the provider. The reply-to directive forces PF to send reply packets back out the interface they arrived on, to the specified next-hop.

The Complete Picture

Here’s how a request to a BGP-addressed jail service flows:

1. Client sends packet to 2a06:9801:1c:1000::10 (web jail)

2. Packet traverses the internet, reaching AS201379 via iFog or Lagrange

3. router01 forwards it through gif0 tunnel to vps01

4. vps01 receives proto 41 on vtnet0, decapsulates --> gif0

5. PF matches: reply-to ($tun_if $bgp_hub_ip), creates state

6. Packet forwarded to bastille0 --> jail

7. Jail responds, packet exits on bastille0

8. PF's state table triggers reply-to: send via gif0 to bgp_hub_ip

9. gif0 encapsulates (proto 41) using FIB 0 to reach router01

10. router01 receives, forwards to upstream --> internet --> client

And for outbound connections initiated by the jail using its BGP address:

1. Jail sends packet from 2a06:9801:1c:1000::10

2. Packet arrives on bastille0

3. PF matches: "from $bgp_net --> rtable 1"

4. Kernel routes via FIB 1 --> default route --> gif0

5. gif0 encapsulates using FIB 0 --> vtnet0 --> router01

6. router01 receives, forwards to internet (source: 2a06:9801:1c:1000::10)

Meanwhile, the exact same jail can communicate using its provider address through the normal default route in FIB 0, with NAT to the host’s address. Both address spaces coexist on the same interface, differentiated purely by PF rules and FIB selection.

Verification

Once everything is running, verification is straightforward. From inside a jail with both addresses:

# Traffic from the provider address - NATed through the hoster

root@caddy:~ # curl --interface 2001:db8:200:0:1000::10 https://ifconfig.co

2001:db8:200::2

# Traffic from the BGP address - routed natively through the tunnel

root@caddy:~ # curl --interface 2a06:9801:1c:1000::10 https://ifconfig.co

2a06:9801:1c:1000::10

The first request shows the host’s NATed provider address. The second shows the jail’s real BGP address - confirming the packet traversed the tunnel and reached the internet through AS201379.

A traceroute from an external host confirms the BGP path is working:

$ mtr -rw 2a06:9801:1c:1000::10

HOST: Loss% Snt Last Avg Best Wrst StDev

1.|-- [local-gateway] 0.0% 10 2.6 5.5 2.6 14.1 3.6

...

9.|-- [transit-provider-edge] 0.0% 10 33.8 46.2 33.8 81.2 19.0

10.|-- [ifog-peering-fabric] 0.0% 10 33.5 46.7 33.5 87.0 18.6

11.|-- 2001:db8:300::2 0.0% 10 44.3 59.1 41.9 136.7 33.2

12.|-- 2a06:9801:1c:ffff::2 0.0% 10 72.7 98.9 68.8 198.8 42.4

13.|-- 2a06:9801:1c:1000::10 0.0% 10 164.1 83.1 63.5 164.1 33.4

Traffic enters via the transit provider (hops 9-10), traverses the GRE tunnel to router01 (hop 11), then the GIF tunnel to vps01 (hop 12, the 2a06:9801:1c:ffff::2 link address), and finally reaches the jail (hop 13). The prefix also shows up correctly on bgp.tools as active and originated by AS201379 with both upstreams visible.

Lessons Learned

MSS clamping is non-negotiable with tunnels. Every layer of encapsulation eats into the MTU. GIF adds 20 bytes (IPv4 header) to every packet. GRE adds more. If you don’t clamp the TCP MSS, large packets get fragmented or dropped, causing mysterious failures where small requests work but large transfers stall. Set max-mss in PF’s scrub rules for every tunnel interface, calculated as: MTU minus IPv6 header (40 bytes) minus TCP header (20 bytes).

FIB separation is cleaner than source-based routing hacks. FreeBSD’s multi-FIB support is a first-class feature. Using rtable in PF and fib/tunnelfib on interfaces gives you full control over which routing table handles which traffic. It’s conceptually cleaner and more debuggable than alternatives like ip6tables MARK targets on Linux.

Bogon filtering matters even for small networks. The internet is full of misconfigurations and occasional malice. Filtering inbound routes prevents your router from accepting nonsense that could black-hole traffic or worse. The cost is a few lines of configuration; the protection is real.

reply-to solves asymmetric routing. When traffic can arrive on multiple interfaces, the kernel’s default FIB selection for return traffic may choose the wrong path. PF’s reply-to directive forces replies back out the arrival interface, which is exactly what you need for tunnel overlay setups.

Start with two upstreams. A single upstream means zero redundancy and no ability to do traffic engineering. Two upstreams give you failover and the ability to prefer one path over the other using AS-path prepending or communities. The operational complexity increase is minimal.

Conclusion

Running your own AS on the internet is more accessible than most people assume. The barrier isn’t technical complexity - it’s knowing that the option exists. A FreeBSD VM, FRR, a couple of tunnels, and some careful PF rules give you provider-independent addressing, real BGP peering, and a deeper understanding of how the internet actually works.

The dual-FIB approach on the downstream server is the piece I’m most satisfied with. It elegantly solves the “two address spaces, one server” problem without hacks: BGP traffic takes the tunnel, provider traffic takes the default route, and PF’s rtable directive makes the decision based purely on source address. Both paths coexist transparently, and the jails don’t need to know anything about the routing underneath.

Is it overkill for a blog? Absolutely. But the same infrastructure carries every service I run, and having addresses that survive provider migrations has already paid for itself in operational simplicity. Besides, there’s something deeply satisfying about seeing your own AS number show up in a traceroute.

References

- RIPE NCC - Requesting Resources

- FRR Documentation

- FreeBSD Handbook: Firewalls (PF)

- FreeBSD setfib(1)

- bgp.tools - BGP looking glass and analytics

- RIPE RPKI Documentation

- RFC 5082 - GTSM (TTL Security)

The internet is a network of networks, and now you’re one of them. There’s a certain elegance in participating in the same routing protocol that glues together every network on the planet - from your single /48 all the way up to the Tier 1 carriers. BGP doesn’t care about your size. It just cares that your routes are valid, your filters are clean, and your packets know where to go.