Devin is cooked, chat.

Posted Dec 21, 2025 by Benjamin Anderson

This September, Cognition (the makers of Devin), raised $400 million at a $10.2 billion valuation. This December, as a late birthday present from me to me, I am declaring Devin officially dead. Why? Because we have Devin at home.

The Appeal of Async Coding Agents

Async coding agents have been "a thing" for a while now. As soon as models were good enough to accomplish even smallish tasks without being talked through each step (probably around the time of Claude Sonnet 3.5 or GPT-4o?), it became feasible and useful to let them do their own thing in the background, and check the results later. Notably, this does not require them to be perfectly accurate, or even close to it. As long as you have money for the tokens, and enough time to look at the output and see if it does what you want, you may as well kick off a coding agent in the background and see if something good happens.

Background agents now seem to be table stakes for startups and AI labs trying to sell coding plans. Cognition (Devin) has always been focused on background agents, which anecdotally, did not work at all when first launched, and now work pretty well. Cursor followed quickly, and OpenAI, Anthropic, and Google now also have background agent offerings (Codex Web, Claude Code Web, and Jules). But from what I can tell, they don't have enormous adoption, in large part because many people still like to babysit their agents, and don't trust them to do things right. It's also possible to substitute 2-5 CLI agents in different terminals without missing out on a whole lot. And of course, there are inconveniences, like cloud agents not having access to environment variables, packages, and such unless you set them up just so.

However, I think the latest crop of models changes the cost-benefit analysis quite a lot. The "may as well try" of 2023 has turned into "Holy shit I have 94 things I want Claude Opus to do, but I only have time to watch it do 8 of them per day." The bottleneck has shifted (at least for me) to deciding what you want done, describing it sufficiently, switching between tasks without forgetting what you were doing and why, and testing the result to avoid regressions. The actual ability to (roughly) do the thing you want is usually not in question. This means that reducing activation energy to spawn agents is more worthwhile, even if it requires paying Anthropic or Cognition some ungodly sum of money, or investing some of your own time to set up the infrastructure yourself.

Why Existing Cloud Agents Aren't Enough

An imaginary interlocutor might say, how could it possibly be easier than it already is? You can just open up your browser or the Claude Desktop app, add a repository, and start spawning background agents to your heart's content. Or you can even add Claude Code to your Slack now. What more do you need? To this interlocutor, I would say: "Good point. But building your own version is more fun." And it can work with any model. And over time I can add more stuff to it, like MCPs, tools, filesystems, and code execution, instead of waiting for Anthropic or OpenAI to add it (the Claude Code and Codex web interfaces are much less flexible/hackable than ChatGPT or Claude). So, on a weekend earlier this month, I decided to do this as a DIY project.

Built in a Day

The title of this post is a bit misleading. Sorry. I didn't really build async coding agents from scratch. Building a full-featured harness like Claude Code is no easy feat. (Although you can make a simple one yourself: see this post from Thorsten Ball at Amp.) Instead, my goal was to take the good harnesses we all know and love, and build the affordances to let them run asynchronously.

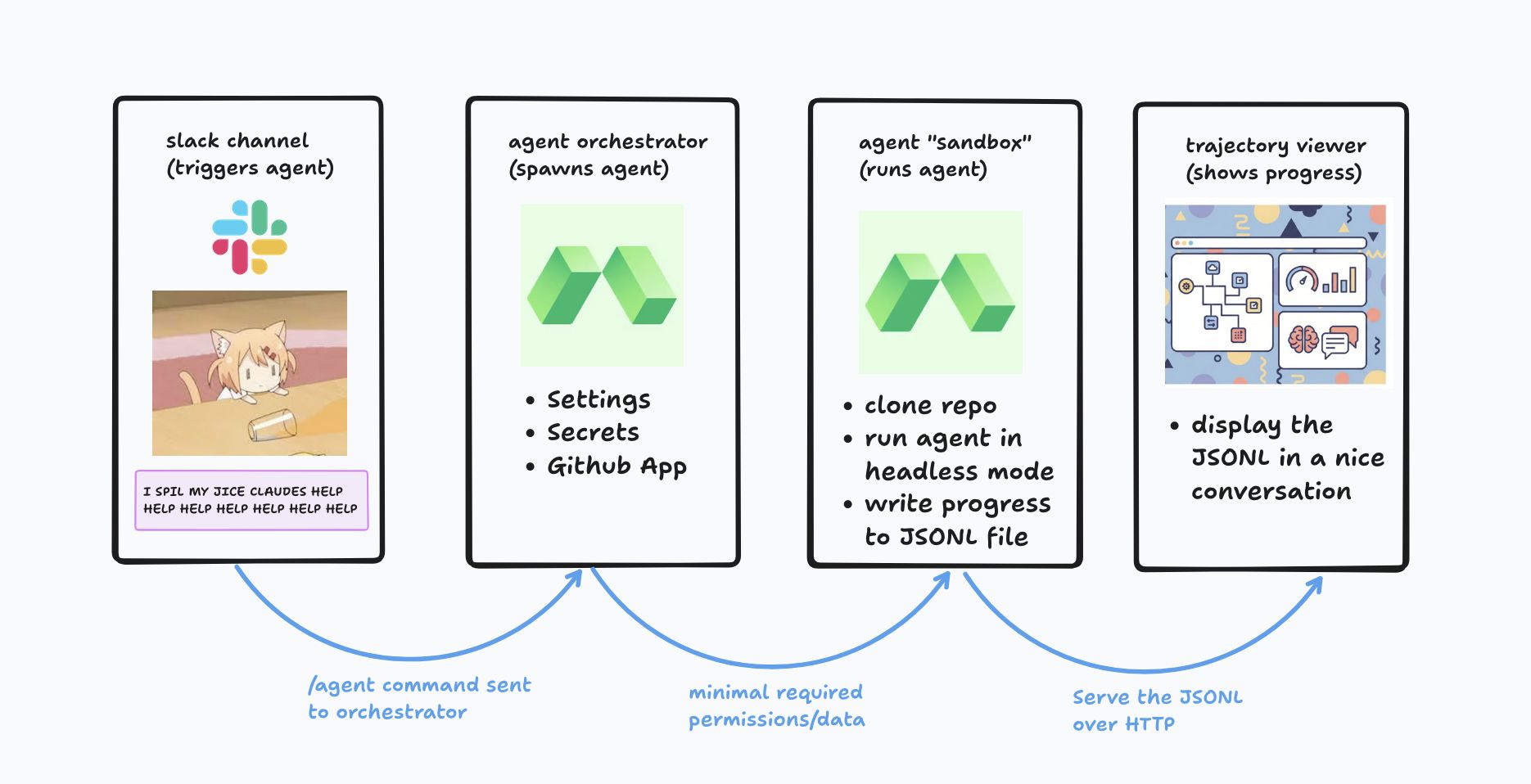

This basically involves combining a few pieces: Slack for triggering agents, a Github app for managing code access, serverless compute, and Claude Code/Codex headless mode. This can be extended to support any harness that can run non-interactively, which includes Codex, the Gemini CLI, OpenCode, Amp, and more.

I'll skip the Slack part because that's easy and boring. For the serverless compute, I started with two Modal functions. The first is the agent "orchestrator." No coding agents run in here—the orchestrator is where the secrets and Github access are managed. Running the /agent command in Slack spins up an orchestrator container, which authenticates with the Github app and generates an ephemeral token with only the required permissions (access to 1 repo, write access only if explicitly requested).

The orchestrator then spins up a second agent Modal container, which is initialized with either an empty project (uv installed and virtual environment activated), or a cloned repo from Github with the aforementioned (read access to 1 repository, write access if push is desired). The orchestrator can also manage secrets, copying over only the API keys needed to run the chosen model. That way, if you're scared of China, Kimi can't access your Anthropic API key. Getting the harnesses to install on Modal was no easy feat (it's meant to deploy Python functions, not NPM packages), but after some persistence, I got the harnesses to run smoothly on Modal.

Perfected in a Week

The initial version was gnarly. Slack commands were received and models ran, but they couldn't actually commit and push their changes (they needed explicit permissions from the harness to run Git commands, which they didn't have). Using Modal Functions (not sandboxes), there wasn't a way to give each agent run its own isolated storage volume, so they shared (not very secure!). If you weren't careful and didn't pass restrict_modal_access, the "locked down" agent container could actually access all deployed apps in your Modal workspace (I already knew not to allow this). There wasn't a good way to look at the agent outputs. But the basics were there! I felt like I'd built Devin in a day. Dialing it in enough to be useful took a bit longer.

The first step was fixing permissions. This just required pre-configuring a bunch of commands that are allowed, getting way more familiar with the Claude Code documentation than I ever really wanted to be. Good permissions to allowlist might include: ["Bash(git commit:*)", "Bash(git checkout:*)", "Bash(git config:*)", "Bash(git add:*)", "Bash(git push:*)"]. These are intentionally broad; we're relying on the scope of the Github App token rather than these permissions to stop the model from pushing if I don't want to allow it to push. There's also things that make make sense to pre-deny, like reading sensitive files, if your repository has any. There's a bunch more interesting stuff here that help deny destructive Git commands; I'll probably add some of these in later.

The second step was going from a Function to a Sandbox for running the agent. I didn't want to do this because CPU and memory are marked up 3-4x on Modal for sandboxes vs. regular containers, but it was the only way to get isolated storage per-agent, and allow each running agent container to open a tunnel for external observability without also giving the LLM access to the entire Modal workspace. But the cost isn't that relevant, because you'll be spending way more on the LLM tokens anyway. However, running things in Modal Sandboxes is more annoying—you have to do everything as a .exec() command, and this doesn't even run with bash, it has to be an executable. So to just run something with bash, you have to do .exec("bash", "-c", "<cmd>"). Oh, and headless Claude Code just chokes and hangs when run this way, unless you pass pty=True, an option that isn't really well-explained in the Modal documentation. But this all eventually was sorted, and as a result, we get stronger isolation and the ability to open an ephemeral tunnel for debugging.

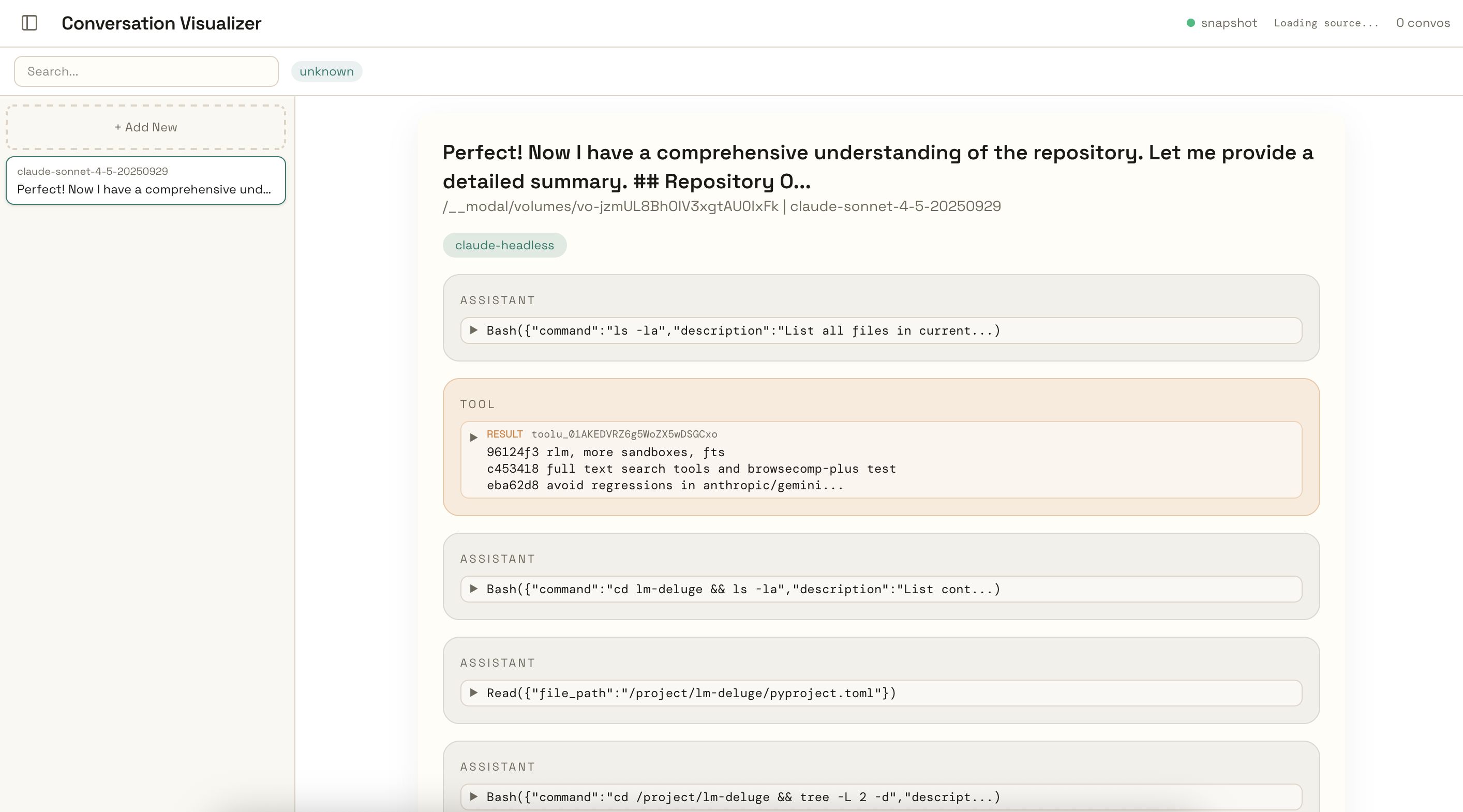

Finally comes making use of that tunnel: providing some useful exhaust for the user to look at while the agent is running, or afterwards. To get structured logs amenable to displaying as a GUI, I have Claude Code/Codex emit JSON streams instead of text (they have this option built in). Each event is appended to a JSONL file as it occurs, and that file is exposed via a simple HTTP server. Then, I spent a good amount of time building CCViewer, a UI that can load in Claude Code and Codex traces and visualize them. I was initially building this separately to view local Claude Code and Codex traces on my computer, but realized it could be extended easily to read these streamed JSONL logs. CCViewer is publicly available (https://ccviewer.com), and by dropping in the server URL of the Modal Sandbox, you can watch the agent's progress as it works.

CCViewer doesn't save your data, but you shouldn't trust me—don't put anything too sensitive in there! I will probably release the source code for it at some point when it's cleaned up a bit. I'm not going to release the source code for the entire coding agent setup, since the whole point of this post is that it's not that special and you can slop it together yourself in a few hours or days.

Conclusion

My goal with this post was to demonstrate that you can homebrew your own asynchronous coding agent pretty easily. I do not actually believe this means no one can build a business selling coding agents in the cloud. However, what it does mean is that merely saying "our agent runs in the cloud in a sandbox and connects to your Slack" is not enough of a differentiator. There should be no local-cloud "arbitrage," where users accept a worse harness or middling performance because oh wow it runs in the cloud! If you are building cloud-based sandboxed coding agents, the baseline to beat is Claude Code and Codex, because I can run those in the cloud with all the customization I want, and so can anyone else. (Not to mention, OpenAI and Anthropic run them in the cloud, albeit with fewer bells and whistles.) I believe the main companies working on coding agents, like Cognition and Cursor, realize this, and are doing everything they can to train their own SWE agent and auxiliary models and improve their harnesses. I'm excited to see what they do in 2026.