“We should not forget the lessons of history. And the lesson is those regulations have been very important.”

Archived hair samples from a baby (right) and adult (left). Credit: Diego Fernandez

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) cracked down on lead-based products—including lead paint and leaded gasoline—in the 1970s because of its toxic effects on human health. Scientists at the University of Utah have analyzed human hair samples spanning nearly 100 years and found a 100-fold decrease in lead concentrations, concluding that this regulatory action was highly effective in achieving its stated objectives. They described their findings in a new paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

We’ve known about the dangers of lead exposure for a very long time—arguably since the second century BCE—so why conduct this research now? Per the authors, it’s because there are growing concerns over the Trump administration’s move last year to deregulate many key elements of the EPA’s mission. Lead specifically has not yet been deregulated, but there are hints that there could be a loosening of enforcement of the 2024 Lead and Cooper rule requiring water systems to replace old lead pipes.

“We should not forget the lessons of history. And the lesson is those regulations have been very important,” said co-author Thure Cerling. “Sometimes they seem onerous and mean that industry can’t do exactly what they’d like to do when they want to do it or as quickly as they want to do it. But it’s had really, really positive effects.”

An American mechanical and chemical engineer named Thomas Midgley Jr. was a key player in the development of leaded gasoline (tetraethyl lead) because it was an excellent anti-knock agent, as well as the first chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) like freon. Midgley publicly defended the safety of tetraethyl lead (TEL), despite experiencing lead poisoning firsthand. He held a 1924 press conference during which he poured TEL on his hand and inhaled TEL vapor for 60 seconds, claiming no ill effects. It was probably just a coincidence that he later took a leave of absence from work because of lead poisoning. (Midgley’s life ended in tragedy: he was severely disabled by polio in 1940 and devised an elaborate rope-and-pulley system to get in and out of bed. That system ended up strangling him to death in 1944, and the coroner ruled it suicide.)

Science also produced a hero in this saga: Caltech geochemist Clair Patterson. Along with George Tilton, Patterson developed a lead-dating method and used it to calculate the age of the Earth (4.55 billion years), based on analysis of the Canton Diablo meteorite. And he soon became a leading advocate for banning leaded gasoline and the “leaded solder” used in canned foods. This put Patterson at odds with some powerful industry lobbies, for which he paid a professional price.

But his many experimental findings on the extent of lead contamination and its toxic effects ultimately led to the rapid phase-out of lead in all standard automotive gasolines. Prior to the EPA’s actions in the 1970s, most gasolines contained about 2 grams of lead per gallon, which quickly adds up to nearly 2 pounds of lead released via automotive exhaust into the environment, per person, every year.

The proof is in our hair

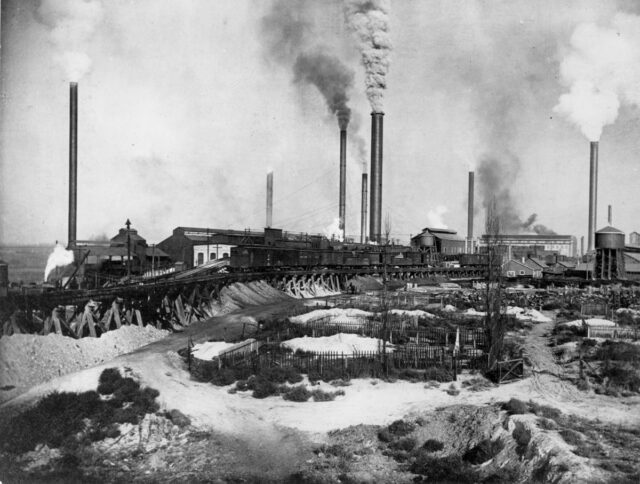

The US Mining and Smelting Co. plant in Midvale, Utah, 1906. Credit: Utah Historical Society

Lead can linger in the air for several days, contaminating one’s lungs, accumulating in living tissue, and being absorbed by one’s hair. Cerling had previously developed techniques to determine where animals lived and their diet by analyzing hair and teeth. Those methods proved ideal for analyzing hair samples from Utah residents who had previously participated in an earlier study that sampled their blood.

The subjects supplied hair samples both from today and when they were very young; some were even able to provide hair preserved in family scrapbooks that had belonged to their ancestors. The Utah population is well-suited for such a study because the cities of Midvale and Murray were home to a vibrant smelting industry through most of the 20th century; most other smelters in the region closed down in the 1970s when the EPA cracked down on using lead in consumer products.

Cerling acknowledged that blood would have been even better for assessing lead exposure, but hair samples are much easier to collect. “[Hair] doesn’t really record that internal blood concentration that your brain is seeing, but it tells you about that overall environmental exposure,” he said. “One of the things that we found is that hair records that original value, but then the longer the hair has been exposed to the environment, the higher the lead concentrations are.”

“The surface of the hair is special,” said co-author Diego Fernandez. “We can tell that some elements get concentrated and accumulated in the surface. Lead is one of those. That makes it easier because lead is not lost over time. Because mass spectrometry is very sensitive, we can do it with one hair strand, though we cannot tell where the lead is in the hair. It’s probably in the surface mostly, but it could be also coming from the blood if that hair was synthesized when there was high lead in the blood.”

The authors found very high levels of lead in hair samples dating from around 1916 to 1969. But after the 1970s, lead concentrations in the hair samples they analyzed dropped steeply, from highs of 100 parts per million (ppm) to 10 PPM by 1990, and less than 1 ppm by 2024. Those declines largely coincide with the lead reductions in gasoline that began after President Nixon established the EPA in 1970. The closing of smelting facilities likely also contributed to the decline. “This study demonstrates the effectiveness of environmental regulations controlling the emissions of pollutants,” the authors concluded.

PNAS, 2026. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2525498123 (About DOIs).

Jennifer is a senior writer at Ars Technica with a particular focus on where science meets culture, covering everything from physics and related interdisciplinary topics to her favorite films and TV series. Jennifer lives in Baltimore with her spouse, physicist Sean M. Carroll, and their two cats, Ariel and Caliban.