All the space that’s fit to print

“Almost from the beginning of the company, I wanted to build a Falcon 9 competitor.”

Stage one of Relativity SpaceX's Terran 1 rocket undergoes testing at Launch Complex-16 in Florida. Credit: Relativity Space

Stage one of Relativity SpaceX's Terran 1 rocket undergoes testing at Launch Complex-16 in Florida. Credit: Relativity Space

Relativity Space is preparing to roll its Terran 1 rocket out to the launch pad in Florida in the next few weeks, setting the stage for its debut flight.

While the rocket is modest in scope, with a capacity to loft about 1 metric ton into low-Earth orbit, the company plans to use this vehicle as a demonstrator for a much larger booster, the Terran R rocket. This ambitious rocket is intended to be a fully reusable vehicle with a payload capacity slightly larger than SpaceX’s Falcon 9 rocket.

“Almost from the beginning of the company I wanted to build a Falcon 9 competitor, because I really think that’s needed in the market,” said Tim Ellis, co-founder and chief executive of Relativity Space, in an interview with Ars.

The impending test flight of Terran 1 may have a lighthearted name—Good Luck, Have Fun—but it has a serious purpose. Relativity needs to show customers that its novel approach to 3D-printed rockets is viable. While ground testing has validated this approach, Ellis knows that the acid test will come with launch, particularly when the vehicle passes through the time period of maximum dynamic pressure, max q.

If the mission successfully demonstrates this, Ellis expects even more customers to sign on for Terran R, which he hopes to begin flying in late 2024. The vehicle is intended to be priced competitively with the Falcon 9 and meet the enormous demand for launch services in the medium-lift market, especially after Russia’s war against Ukraine removed the Soyuz vehicle as an option for Western companies.

But first things first.

Terran 1

Relativity recently completed first-stage hot-fire testing of the Terran 1 rocket, and engineers and technicians are now attaching the second stage to the rocket. In a few weeks, the completed vehicle will roll back out to Launch Complex-16 at Cape Canaveral Space Force Station in Florida for a static fire test and, assuming that goes well, a launch attempt.

“We are confident in our tech readiness to launch this year, and we’re still marching toward that,” Ellis said. “But there are a few external factors as we’re getting close to the end of the year that could impact the timeline for us. It’s not a guarantee, but it could.”

Those external factors include other spaceport users in Florida, including uncertainty around the mid-November launch of NASA’s Space Launch System rocket, and blackout periods as part of the military’s Holiday Airspace Release Plan. This effectively precludes launches around Thanksgiving, Christmas, and New Year’s Day due to the high volume of airline flights.

Ellis said the company is progressing well toward securing a launch license for “Good Luck Have Fun,” and noted that the Federal Aviation Administration accepted its methodology for debris mitigation as well as its trajectory analysis software.

No privately funded company has ever reached orbit on its very first rocket launch, and Ellis is cognizant of that. “While the rocket-loving engineer in me wants to say it’s really orbit or nothing for the first flight, I think the business leader part of me knows that customers are going to tell us what enough looks like for the first flight.”

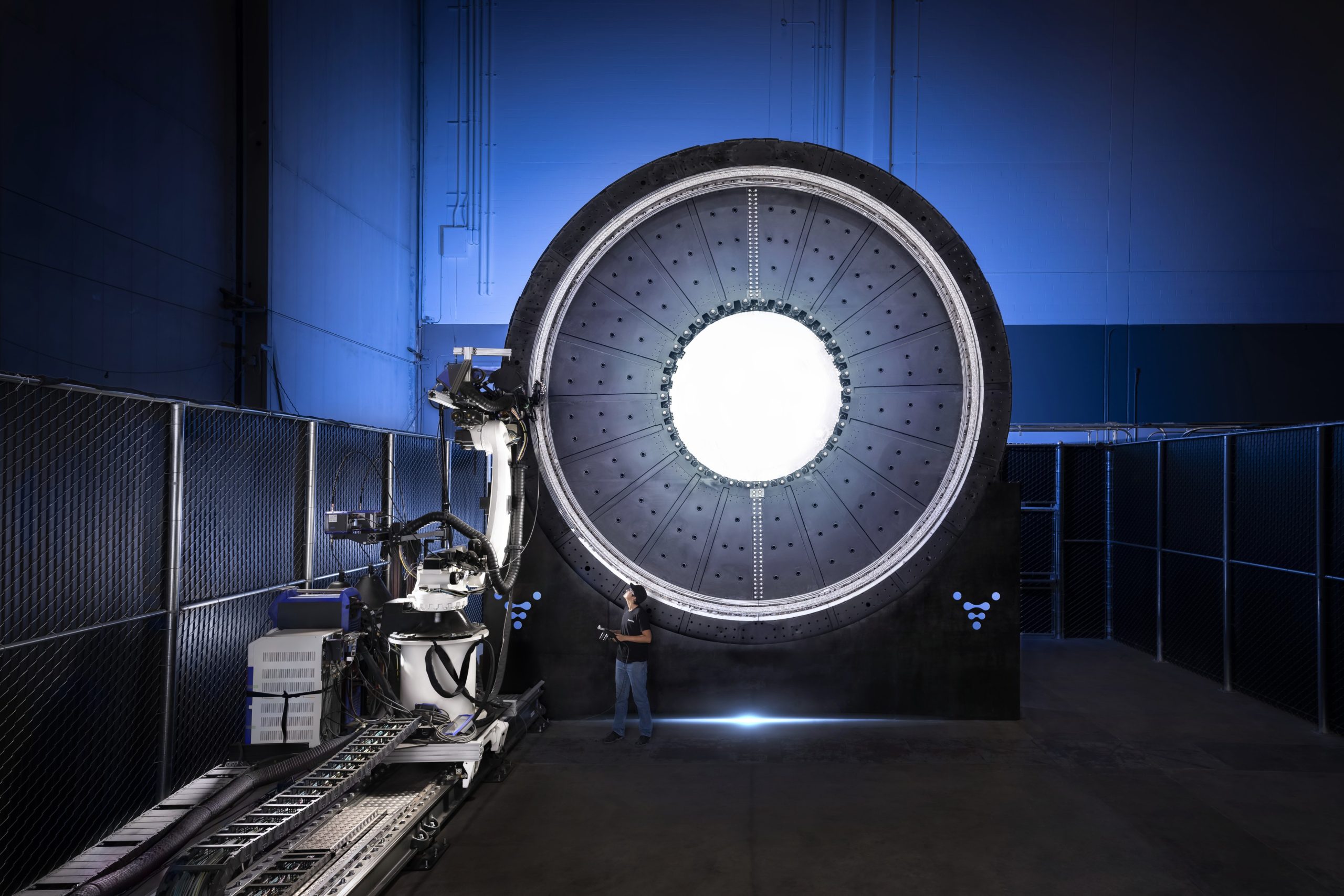

Relativity recently installed the first of its new “fourth generation” Stargate printers at its headquarters in Southern California.

Credit: Relativity Space

Relativity recently installed the first of its new “fourth generation” Stargate printers at its headquarters in Southern California. Credit: Relativity Space

What customers want to see, he said, is a demonstration that a 3D-printed rocket can withstand the rigors of launch. At its core, Relativity is an additive manufacturing company, with the goal of printing the majority of its rockets. By mass, about 85 percent of the Terran 1 is additively manufactured. Can these structures survive max q?

“In many ways Terran 1 is about proving the hypothesis that 3D-printing a rocket is viable,” Ellis said. “Doing stage testing on the ground, the structural testing, in my mind, has already really proven the rocket structures that are 3D-printed are strong enough. But I think from a customer perspective, hitting max q becomes an important moment in terms of validating this additive manufacturing model and tech platform. From a visceral perspective on an actual launch, that’s really the moment.”

Of course, if Terran 1 does reach orbit on its first attempt, it would be a real breakthrough. In addition to becoming the first private company to reach orbit with a vertically launched rocket on the first try, Terran 1 would be the first methane-fueled rocket to launch and also the first one that was built primarily from 3D-printed parts.

Terran R

Ellis said the second flight of Terran 1 would launch a payload for NASA but would not make a firm commitment to any other missions on Terran 1. “A lot of focus right now is on Flight One,” he said. “And we’re also quite focused on just continuing to do Terran R milestones because we’ve sold so many.”

The reality is that customers are not all that interested in a 1-ton class rocket, he said. Rather, they prefer a medium-lift vehicle than can lift 20 or more tons in a single launch. Relativity has sold $1.2 billion worth of launches on Terran R and has a “few hundred” million more dollars’ worth of contracts under negotiation with customers.

And so Relativity is pressing ahead full-bore with Terran R, investing several hundreds of millions of dollars into the project this year and doing as much or more in 2023. (As of its last fundraising round in 2021, Relativity had raised $1.3 billion.) The company currently has nearly 1,000 employees, and a majority of them are working on Terran R, with the goal of completing the full-scale Aeon R engine test about 12 months from now and launching in two years.

Ellis said the plan was to move swiftly from Terran 1, as a demonstrator, into Terran R from the beginning. As a result, the smaller vehicle is more complex than it needs to be, with nine engines that use methane propellant, an “autogenous” pressurization system for its propellant tanks, and new igniters not based on TEA-TEB.

“We’ve bitten off a lot more upfront on the Terran 1 learning so that we can roll it into the Terran R, and get there faster,” Ellis said. “That’s some insight into why customers are so excited about Terran R, because when they visit the launch site and look at Terran 1, a lot of their reaction is, ‘Wow, this looks more like a miniature Falcon 9 than it does a cubesat launch vehicle.’”

In a few months, probably after the Terran 1 launch, Ellis plans to provide a “comprehensive” update on Terran R to talk about plans for reusability. However, initially, the vehicle will fly in an expendable mode to meet the demands of customers who want a medium-lift rocket, sooner. Much as SpaceX experimented with reusing the first stage, Relativity will practice water landings as well. Second stage reuse will also be folded in over time.

But rest assured, Ellis said that full reuse is coming. It’s the future of Relativity Space and, he believes, the industry, as SpaceX develops Starship and other companies have revealed plans for such vehicles.

“They can’t be the only one disruptive medium- to heavy-lift launch company,” he said. “Relativity is certainly playing to win.”

Listing image: Relativity Space

Eric Berger is the senior space editor at Ars Technica, covering everything from astronomy to private space to NASA policy, and author of two books: Liftoff, about the rise of SpaceX; and Reentry, on the development of the Falcon 9 rocket and Dragon. A certified meteorologist, Eric lives in Houston.