Credit: Ben Orlin

The next turn falls to Zoe who asks, “Xia, do you have any Scruples?”

This means Zoe’s final card is a Scruple. Indeed, it’s the last Scruple, which means that Xia can’t possibly have one. Why did Zoe even bother to ask?

Because, with all the Scruples and Qualms accounted for, Zoe knows that Xia’s remaining cards are Narwhals. By declaring and explaining this knowledge, Zoe wins the game. (Xia, despite ending the game with all four Narwhals, began with only three, later gaining one from Zoe.) Easy like Sunday morning, right?

Credit: Ben Orlin

Physical version

Some mathematicians I know like to forbid pencil and paper, forcing you to keep track of the game entirely in your head. “Though that’s fun,” says Anton Geraschenko, “I came up with a physical deck for playing the game which automatically does a lot of the bookkeeping for you, freeing your brain cycles up to strategize.”

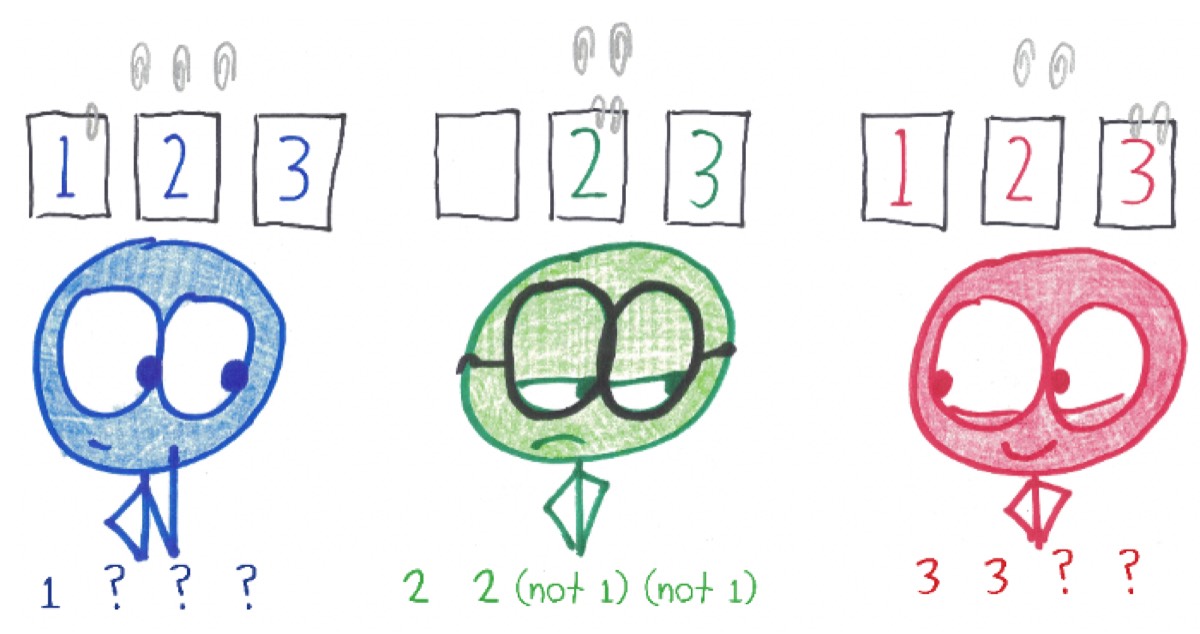

I heartily recommend Anton’s system. Here’s what you need:

- Four paper clips per player (representing your cards).

- Assuming you have n players, each player needs face-up pieces of paper numbered 1 to n(representing the possible suits that you might possess).

As you play, keep track of the evolving game state via these steps:

- If you determine that you have none of a suit (because you’ve answered “No” or because others have them all), turn the corresponding piece of paper facedown.

- Your unattached clips may belong to any of the face-up suits.

- If you determine a card’s suit, attach that paper clip to the corresponding piece of paper. If you have multiple of that suit, attach multiple clips.

Credit: Ben Orlin

Where it comes from

The game has circulated for years among mathematicians. I’ve adapted my description from Anton Geraschenko, who encountered the game in the math Ph.D. program at UC Berkeley, where our mutual pal David Penneys was its biggest cheerleader.

Folks there often played it as a drinking game, which I find equal parts insane and inspiring. Whereas most drinking games create runaway positive feedback cycles—losing makes you drink, which makes you drunk, which makes you lose, which makes you drink—this one is played with a healthier negative feedback loop, in which someone who makes an error is forbidden from drinking for the next round.

Anyway, Anton learned it from Scott Morrison, who credits Dylan Thurston, who doesn’t know who invented the game but shared with me his earliest record of it: a 2002 email, signed by himself and Chung-chieh Shan. If anyone knows the game’s deeper historical (or quantum) origins, please contact me on Twitter: @benorlin.

Ars Technica may earn compensation for sales from links on this post through affiliate programs.