"Unauthorized Bread"—a tale of jailbreaking refugees versus IoT appliances—is the lead novella in author Cory Doctorow's Radicalized, which has just been named a finalist for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation's national book award, the Canada Reads prize. "Unauthorized Bread" is also in development for television with Topic, parent company of The Intercept; and for a graphic novel adaptation by First Second Books, in collaboration with the artist and comics creator JR Doyle. It appears below with permission from the author.

The way Salima found out that Boulangism had gone bankrupt: her toaster wouldn’t accept her bread. She held the slice in front of it and waited for the screen to show her a thumbs-up emoji, but instead, it showed her the head-scratching face and made a soft brrt. She waved the bread again. Brrt.

“Come on.” Brrt.

She turned the toaster off and on. Then she unplugged it, counted to ten, and plugged it in. Then she menued through the screens until she found RESET TO FACTORY DEFAULT, waited three minutes, and punched her Wi-Fi password in again.

Brrt.

Long before she got to that point, she’d grown certain that it was a lost cause. But these were the steps that you took when the electronics stopped working, so you could call the 800 number and say, “I’ve turned it off and on, I’ve unplugged it, I’ve reset it to factory defaults and…”

There was a touchscreen option on the toaster to call support, but that wasn’t working, so she used the fridge to look up the number and call it. It rang seventeen times and disconnected. She heaved a sigh. Another one bites the dust.

The toaster wasn’t the first appliance to go (that honor went to the dishwasher, which stopped being able to validate third-party dishes the week before when Disher went under), but it was the last straw. She could wash dishes in the sink but how the hell was she supposed to make toast—over a candle?

Just to be sure, she asked the fridge for headlines about Boulangism, and there it was, their cloud had burst in the night. Socials crawling with people furious about their daily bread. She prodded a headline and learned that Boulangism had been a ghost ship for at least six months because that’s how long security researchers had been contacting the company to tell it that all its user data—passwords, log-ins, ordering and billing details—had been hanging out there on the public internet with no password or encryption. There were ransom notes in the database, records inserted by hackers demanding cryptocurrency payouts in exchange for keeping the dirty secret of Boulangism’s shitty data handling. No one had even seen them.

Boulangism’s share price had declined by 98 percent over the past year. There might not even be a Boulangism anymore. When Salima had pictured Boulangism, she’d imagined the French bakery that was on the toaster’s idle-screen, dusted with flour, woodblock tables with serried ranks of crusty loaves. She’d pictured a rickety staircase leading up from the bakery to a suite of cramped offices overlooking a cobbled road. She’d pictured gas lamps.

The article had a street-view shot of Boulangism’s headquarters, a four-story office block in Pune, near Mumbai, walled in with an unattended guard booth at the street entrance.

The Boulangism cloud had burst and that meant that there was no one answering Salima’s toaster when it asked if the bread she was about to toast had come from an authorized Boulangism baker, which it had. In the absence of a reply, the paranoid little gadget would assume that Salima was in that class of nefarious fraudsters who bought a discounted Boulangism toaster and then tried to renege on her end of the bargain by inserting unauthorized bread, which had consequences ranging from kitchen fires to suboptimal toast (Boulangism was able to adjust its toasting routine in realtime to adjust for relative kitchen humidity and the age of the bread, and of course it would refuse to toast bread that had become unsalvageably stale), to say nothing of the loss of profits for the company and its shareholders. Without those profits, there’d be no surplus capital to divert to R&D, creating the continuous improvement that meant that hardly a day went by without Salima and millions of other Boulangism stakeholders (never just “customers”) waking up with exciting new firmware for their beloved toasters.

And what of the Boulangism baker-partners? They’d done the right thing, signing up for a Boulangism license, subjecting their process to inspections and quality assurance that meant that their bread had exactly the right composition to toast perfectly in Boulangism’s precision-engineered appliances, with crumb and porosity in perfect balance to absorb butter and other spreads. These valued partners deserved to have their commitment to excellence honored, not cast aside by bargain-hunting cheaters who wanted to recklessly toast any old bread.

Salima knew these arguments, even before her stupid toaster played her the video explaining them, which it did after three unsuccessful bread-authorization attempts, playing without a pause or mute button as a combination of punishment and reeducation campaign.

She tried to search her fridge for “boulangism hacks” and “boulangism unlock codes” but appliances stuck together. KitchenAid’s network filters gobbled up her queries and spat back snarky “no results” screens even though Salima knew perfectly well that there was a whole underground economy devoted to unauthorized bread.

She had to leave for work in half an hour, and she hadn’t even showered yet, but goddamnit, first the dishwasher and now the toaster. She found her laptop, used when she’d gotten it, now barely functional. Its battery was long dead and she had to unplug her toothbrush to free up a charger cable, but after she had booted it and let it run its dozens of software updates, she was able to run the darknet browser she still had kicking around and do some judicious googling.

She was forty-five minutes late to work that day, but she had toast for breakfast. Goddamnit.

The dishwasher was next. Once Salima had found the right forum, it would have been crazy not to unlock the thing. After all, she had to use it and now it was effectively bricked. She wasn’t the only one who had the Disher/Boulangism double whammy, either. Some poor suckers also had the poor fortune to own one of the constellation of devices made by HP-NewsCorp—fridges, toothbrushes, even sex toys—all of which had gone down thanks to a failure of the company’s cloud provider, Tata. While this failure was unrelated to the Disher/Boulangism doubleheader, it was pretty unfortunate timing, everyone agreed.

The twin collapse of Disher and Boulangism did have a shared cause, Salima discovered. Both companies were publicly traded and both had seen more than 20 percent of their shares acquired by Summerstream Funds Management, the largest hedge fund on earth, with $184 billion under management. Summerstream was an “activist shareholder” and it was very big on stock buybacks. Once it had a seat on each company’s board—both occupied by Galt Baumgardner, a junior partner at the firm, but from a very good Kansas family—they both hired the same expert consultant from Deloitte to examine the company’s accounts and recommend a buyback program that would see the shareholders getting their due return from the firms, without gouging so deep into the companies’ operating capital as to endanger them.

It was all mathematically provable, of course. The companies could easily afford to divert billions from their balance sheets to the shareholders. Once this was determined, it was the board’s fiduciary duty to vote in favor of it (which was handy, since they all owned fat wads of company shares) and a few billion dollars later, the companies were lean, mean, and battle ready, and didn’t even miss all that money.

Oops.

Summerstream issued a press release (often quoted in the forums Salima was now obsessively haunting) blaming the whole thing on “volatility” and “alpha” and calling it “unfortunate” and “disappointing.” They were confident that both companies would restructure in bankruptcy, perhaps after a quick sale to a competitor, and everyone could start toasting bread and washing dishes within a month or two.

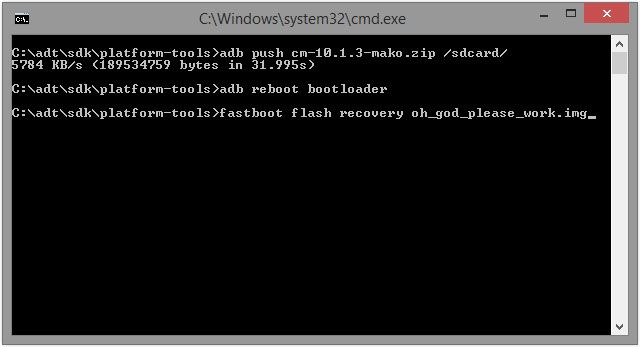

Salima wasn’t going to wait. Her Boulangism didn’t go easily. After downloading the new firmware from the darknet, she had to remove the case (slicing through three separate tamper-evident seals and a large warning sticker that threatened electrocution and prosecution, perhaps simultaneously, for anyone foolish enough to ignore it) and locate a specific component and then short out two of its pins with a pair of tweezers while booting it. This dropped the toaster into a test mode that the developers had deactivated, but not removed. The instant the test screen came up, she had to jam in her USB stick (removing the toaster’s hood had revealed a set of USB ports, a monitor port, and even a little Ethernet jack, all stock on the commodity single-board PC that controlled it) at exactly the right instant, then use the on-screen keyboard to tap in the log-in and password, which were “admin” and “admin” (of course).

It took her three tries to get the timing right, but on the third try, the spare log-in screen was replaced with the pirate firmware’s cheesy text-art animation of a 3-D skull, which she smiled at—and then she burst into laughter as a piece of text-art toast floated into the frame and was merrily chomped to crumbs by the text-art skull, the crumbs cascading to the bottom of the screen and forming shifting little piles. Someone had put a lot of effort into the physics simulation for that ridiculous animation. It made Salima feel good, like she was entrusting her toaster to deep, serious craftspeople and not just randos who liked to pit their wits against faceless programmers from big, stupid companies.

The crumbs piled up as the skull chomped and the progress indicator counted up from 12 percent to 26 percent then to 34 percent (where it stuck for a full ten minutes, until she was ready to risk really bricking the damned thing by unplugging it, but then—) 58 percent, and so on, to an agonizing wait at 99 percent, and then all the crumbs rushed up from the bottom of the screen and went back out through the skull’s mouth, turning back into toast, each reassembled piece forming up in ranks that quickly blotted out the skull, and the words ALL DONE burned themselves into the toast’s surface, glistening with butter that ran down in rivulets. She was just grabbing for her phone to get a picture of this awesome pirate load-screen when the toaster oven blinked and rebooted itself.

A few seconds later, she held a slice of bread to the toaster’s sensor and watched as its light turned green and its door yawned open. Halfway through munching the toast, she was struck by an odd curiosity. She held her hand up to the toaster, palm out, as though it, too, were a slice of bread. The toaster’s light turned green and the door opened. She was momentarily tempted to try and toast a fork or a paper towel or a slice of apple, just to see if the toaster would do it, but of course it would.

This was a new kind of toaster, a toaster that took orders, rather than giving them. A toaster that would give her enough rope to hang herself, let her toast a lithium battery or a can of hairspray, or anything else she wanted to toast: unauthorized bread. Even homemade bread. The idea made her feel a little queasy and a little tremorous. Homemade bread was something she’d read about in books, seen in old dramas, but she didn’t know anyone who actually baked bread. That was like gnawing your own furniture out of whole logs or something.

The ingredients turned out to be incredibly simple, and while her first loaf came out looking like a poop emoji, it tasted amazing, still warm from the little toaster, and if anything, the slice (OK, the lump) she saved and toasted the next morning was even better, especially with butter on it. She left for work that day with a magical, warm, toasty feeling in her stomach.

She did the dishwasher that night. The Disher hackers were much more utilitarian in their approach, but they also were Swedish, judging from the URLs in their README files, which might explain the minimalism. She’d been to an Ikea, she got it. The Disher didn’t require anything like the song and dance of the Boulangism: she popped off the maintenance cover, pried the rubber gasket off the USB port, stuck in her stick, and rebooted it. The screen showed a lot of scrolling text and some cryptic error messages and then rebooted again into what looked like normal Disher operating mode, except without the throbbing red alerts about the unreachable server that had haunted it for a week. She piled the dishes from the sink into the dishwasher, feeling a tiny thrill every time the dishwasher played its “New Dish Recognized” arpeggio.

She thought about taking up pottery next.

IoT(oast) Credit: Björn Birkhahn / EyeEm / Getty Images

Her experience with the dishwasher and the toaster changed her, though she couldn’t quite say how at first. Leaving the apartment the next day, she’d found herself eyeing up the elevator bank, looking at the fire-department override plate under the call screen, thinking about the fact that the tenants on the subsidized floors had to wait three times as long for an elevator because they were only eligible to ride in the cars that had rear-opening doors that exited into the back lobby with its poor-doors. Even those cars wouldn’t stop at her floor if they’d picked up one of the full-fare residents on the way, because heaven forfend those people should have to breathe the common air of the filthy commoners.

Salima had been overjoyed to get a spot in her building, the Dorchester Towers, because the waiting list for the subsidy units that the planning department required of the developer was years deep. She’d been in the country for a decade at that point, spending the first five years in a camp in Arizona where they’d watched one person after another die in the withering heat. When the State Department finally finished vetting her and let her out, a caseworker met her with a bag of clothes, a prepaid debit card, and the news that her parents had died while she was in the camp.

She absorbed the news silently and didn’t allow herself to display any outward sign of her agony. She had assumed that her parents had died, because they’d promised to meet her in Arizona within a month of her arrival, just as soon as her father could call in his old debts and pay for the papers and database fiddling that would get him on the plane and to the U.S. Immigration checkpoint where they could claim asylum. She’d been a teenager then, and now she was a young woman, with five years’ hard living in the camp behind her. She knew how to control her tears. She thanked the caseworker and asked what had become of their bodies.

“Lost at sea,” the woman said and donned a compassionate mask. “The ship and all its passengers. No survivors. The Italians scoured the area for weeks and found nothing. The wreck went straight to the bottom. Bad informatics, they said.” A ship was a computer that you put desperate people inside, and when the computer went bad, the ship was a tomb you put desperate people inside.

She nodded like she understood, though the sound of her blood in her ears was so loud she couldn’t hear herself think. The social worker said more things, and gave her some paperwork, which included a Greyhound ticket to Boston, where she had been found a shelter bed.

She read the itinerary through three times. She’d learned to read English in the camp, taught by a woman who’d been a linguistics professor before she was a refugee. She’d learned geography from the mandatory civics lessons she’d gone to every two weeks, watching videos about life in America that were notably short on survival tips for life in the part of America where they slept three-deep in bunk beds in a blazing desert, surrounded by drones and barbed wire. She’d learned where Boston was, though. Far.

“Boston?”

“Two days, seventeen hours,” the social worker said. “You’ll get to see all of America. It’s an incredible experience.” Her mask slipped for a moment and she looked very tired. Then she pasted her smile back on. “Get to the grocery store first, that’s my advice. You’ll want some real food to eat.”

Salima had got good at being bored over her five years in the camp, mastering a kind of waking doze where her mind simply went away, time scurrying past like roaches clinging to the baseboard, barely visible in the corner of her eye. But on the Greyhound bus, the skill failed her. Even after she found a window seat—twenty-two hours into the journey—she found her mind returning, again and again, to her parents, the ship, the deep fathoms of the Mediterranean. She had known that her parents were dead, but there was knowing, and there was knowing.

She debarked in Boston two days and seventeen hours later, noting as she did that the bus didn’t have a driver, something she’d missed, boarding and debarking by the rear doors. Another computer you put your body into. Given the wrong informatics, the Greyhound could have plunged off a cliff or smashed into oncoming traffic.

There’d been a charge port on the armrest, and she’d shared it with the seatmates who’d come and gone on her bus, but she made sure she had a full charge when she stepped off the bus, and it was good she did, as she used up almost all of her battery getting translations and directions in order to find the shelter she’d been assigned, which wasn’t in Boston, but in a suburb called Worcester, whose pronunciation evaded her for the next six months.

All her groceries were consumed, and everything she owned fit into a duffel bag whose strap broke as she was lugging it up a broken escalator while changing underground T trains on her way to Worcester. She’d spent half the funds on her debit card on food, and had eaten like a mouse, like a bird, like a scurrying cockroach. She had started with nearly nothing and now she had nothing.

The hardest part of finding the shelter was the fact that it was in a dead strip mall, eleven stores all refitted with bunks and showers and playrooms for kids, arranged along the back plane of an empty parking lot that was half a mile from the nearest bus stop. Salima walked past the mall three times, staring at her phone—whose battery was nearly flat again; it was so old it barely held a charge—before she figured out that this row of shops was her new home.

The reception was in an old pharmacy that had anchored the mall. It was unattended, a cavernous space walled off by a roll-down gate, with a row of touchscreens where the cash registers had sat. It smelled of piss and the floor was dirty, with that kind of ancient, ground-in grime you got in places where people trudged over and over.

Only one of the touchscreens was working, and it took a lot of trial and error before she figured out that she needed to tap about 1.5 centimeters south-southwest of the buttons she was hitting. Once she clocked this, things got faster. She switched the screen to Arabic, let the camera over it scan her retinas, and repeatedly pressed her fingers to the pad until the machine had read her. Once it had validated her, she had to tap through eight screens of things she was promising: that she wouldn’t drink or drug or steal; that she didn’t have any chronic or infectious diseases; that she did not support terrorism; that she understood that at this stage, she was not permitted to work for wages, but that also and paradoxically, she would be required to work in Worcester in order to pay back the people of the United States for the shelter bed she was about to be assigned.

She read the fine print. It was something she’d learned to do, early in the refugee process. Sometimes the immigration officers quizzed you on the things you’d just clicked through and if you couldn’t answer their questions correctly, they’d send you back to the back of the line, or reschedule your hearing for the next month, because you hadn’t fully appreciated the gravity of the agreement you were forging with the USA.

Then she found out which of the former stores she’d be living in, and was prompted to insert her debit card, which was topped up with credits she could exchange for food at specific stores that catered to people on benefits. As she tapped through more screens, entering her phone number, choosing times for medical checkups, she became aware of a low humming noise, growing closer. She turned around and saw a low trolley trundling through the aisles of the derelict pharmacy, with a cardboard banker’s box on it. It steered laboriously around corners, then moved to a gate set into the roll-down cage, which clunked open. The screen prompted her to retrieve the box, which contained linens, a towel, a couple six-packs of white cotton underwear, t-shirts, a box of tampons, and a toilet bag with shampoos, soaps, and deodorants. It was the most functional transaction she’d had in … years … and she wanted to kiss the stupid unlovely little robot.

She couldn’t carry her box and her duffel bag at the same time, and she didn’t want to let either out of her sight, so she staged them down the face of the strip mall, moving the box ten paces, setting it down and getting her duffel and carrying it ten paces past the box, then leapfrogging the box over the duffel. Her pile of papers from the kiosk included a map showing the location of her storefront, near the end (of course), so it was a long way. At the halfway mark, a woman came out of the store she’d just passed and regarded her with hands on hips, head cocked, a small smile on her face.

The woman was Somali—there’d been plenty in the camp—and no older than Salima, though she had a small child clinging to her legs, gender unknown. She wore overalls and a Boston University sweatshirt and had her hair in a kerchief, and for all that, she looked somehow stylish. Later, Salima would learn that the woman—whose name was Nadifa—came from a long line of seamstresses and would unpick the seams on any piece of clothing that fell into her hands and re-tailor them for her measurements.

“You are new?”

“I am Salima. I’m new.”

The woman cocked her head the other way. “Where are you staying? Show me.” She walked to Salima and held out her hand for the map. Salima showed it to her and she chupped her teeth. “That’s no good, that one has bad heat and the toilet never stops running. Gah—here, let us fix it.”

Without asking, the woman hoisted her box, and led her back to the office, Salima trailing after her alongside the little child, who kept sneaking her looks. The woman knew which screen worked and could land her finger at the exact south-southwestern offset needed to hit the buttons. Her fingers flew over the screen and then she had Salima stand before the retina monitor and put her fingers on the scanner again, and new paper emerged in the kiosk’s out tray.

“Much better,” the woman said. Salima felt confused and a little anxious. Had this woman just moved her in with her family? Was she to be a babysitter for the child who was staring at her again?

But she didn’t need to worry. Single women stayed in one of three units, and families in two more. Salima’s new home—thanks to the woman, who finally introduced herself—had once been a nail salon, and its storeroom still had a few remnants from those days, but it was now hung with heavy, sound-absorbing blankets made out of some kind of synthetic fiber that turned out to be surprisingly good at shedding dirt and dampening sound. The woman and her kid left her there, and she pulled the fabric corners shut and tabbed them together and spent a moment in the ringing silence of the tiny curtained roomlet, a place that would truly be hers, shared with no one, for some indeterminate time.

Later, she’d discover all the ways that the other shelter-dwellers had decorated their little spaces, which most of them called cells, with heavy irony, because every one of them had spent months or years in literal cells, the kinds with concrete walls and iron bars. She’d decorate her own room, and Nadifa’s children would come to poke their heads in without warning and demand stories or someone to play a game with or ideas for pictures to draw. She wasn’t exactly roped into being a babysitter, but she wasn’t exactly not roped into it, either, and she liked Nadifa’s kids, who were just as bold and fearless as their mother, who was also a lot of fun, especially when she found a bottle of wine and sent the kids out to play in the common room, and they’d perch at opposite ends of Salima’s narrow bunk, telling lies about men, and sometimes the odd truth about their lives before the shelter would slip in, and there’d be a tear or two, but that was all right, too.

Nadifa already had her work papers and she showed Salima how to get papers of her own, which took months of patient prodding at the one working kiosk to get it to emit pieces of paper that she’d have to bring to government offices and feed into other kiosks, sneaking the trips in between her work details. The irony of being too busy working to get a work permit did not escape her, and oh, how she laughed at the irony as she scrubbed graffiti and picked up trash in the parks and cleaned city buses in the great bus-barns in places even more out of the way than her Worcester strip mall.

Getting her work papers wasn’t the same as getting a job, but Salima was smart and she’d spent her years in the camp pursuing different qualifications by online course—hair braiding and bookkeeping, virus removal and cat grooming—and she felt sure there’d be something she could do. She searched the job boards with Nadifa’s help, enrolled with temp agencies, submitting to their humiliating background checks, which included giving them access to her social media and email history, an invasion that was only made worse when she was later quizzed on the messages she’d saved from her parents, videos and picture-messages sent after they’d been separated, but before they’d both died.

Work trickled in, a few hours here and there, shifts dwarfed by the long commutes on the bus to and from the jobs, but she cherished hope that taking these shitty jobs would build her rep with the agencies that were sending her out, that she’d pay her dues and start getting real shifts, for real money. She bought a couple external batteries for her ailing phone so that she could work on the bus rides. She and Nadifa had divided up the entirety of New England and every day they ran hundreds of searches to look for new high-rise approvals that came with subsidized apartments and then made a note of the day that the waiting list for each would open. They knew the chances of either one of them getting accepted were vanishingly small, and if they were both accepted, it was pretty much impossible that they’d end up in a place together.

Which is why the Dorchester Towers were such a miracle. It was bitter December and the shelter hadn’t ever gotten its promised shipment of winter coats, so everyone was making do with multiple layers of sweaters and tees, which didn’t read as “professional” and had cost Salima a very good weeklong bookkeeping job for a think tank that was closing its quarterly books. She’d been worried sick about losing the job and, worse, getting a black mark with the temp agency, which had got her several other great bookkeeping jobs that had fattened her tiny savings account more than a dozen cleaning jobs.

Rattling around the strip mall with the other denizens trapped by the weather and the inadequate clothes, she pondered raiding her savings for a coat, trying to figure out how much work she’d have to lose before it would be a break-even proposition and estimating the probability that the long-delayed winter-coat shipment would finally arrive before too much work was lost. Her phone let her know she had a government message—the kind that she would have to retrieve from the kiosk in the shelter office—so she put on three sweaters and stuffed her hands into three thicknesses of socks and fought the gale-force winds to the office.

Standing in a puddle of her own meltwater, she logged into a kiosk—they’d fixed them all, including the one that sort of worked, and now all of them were equally unreliable and prone to falling into an endless reboot cycle—and retrieved the message. She was just absorbing the impossibly good news when Nadifa staggered in from the cold, carrying her smallest one close to her for body heat.

“Does that one work?” She pointed at Salima’s kiosk and Salima smiled to herself as she wiped the screen and stepped away from it.

“It works!” Her joy was audible in her voice, and Nadifa gave her a funny look. Salima stifled her grin. She’d tell Nadifa when—

“Oh my God.” Nadifa was just staring at the screen, jaw on her chest. Salima peeked and laughed aloud.

“Me too, me too!”

The message was that Dorchester Towers had approved Nadifa’s residency, with a two-room flat on the forty-second story that would be ready to move into in eighteen months, assuming no construction delays. The rent was income-indexed, meaning that Nadifa and her kids would be able to afford to live there no matter what happened to them in the future. Nadifa was sometimes loud and pushy, but she was never squeaky, so it amused Salima quite a lot when Nadifa threw her hands into the air and bounced up and down on her toes, making excited noises so high-pitched they’d have deafened a dolphin.

She didn’t even stop bouncing when she hugged Salima, pulling her along as she jumped up and down, laughing with delight, and Salima laughed even harder, because of what she knew.

She logged Nadifa out of the kiosk and logged herself in and quickly tapped her way into her official government mailbox, and simply pointed wordlessly at the screen until Nadifa bent and read it. Her jaw dropped even further.

“You’re on the thirty-fifth floor! That’s only seven floors below us! We can take the stairs to each other’s places!” Nadifa’s smallest child, confused by all the shouting and bouncing, chose that moment to set up a wail, and so Nadifa pulled him out of his sling and twirled him around over her head. “We’re getting a place, a place of our own! And Auntie Salima will be there, too! We’ll have a kitchen, we’ll have bedrooms, we’ll have—” She broke off and cradled the boy under one arm, used her free hand to grab Salima and shake her by the shoulder. “We’ll have bathrooms. Our own bathrooms! Our own bathtubs! Our own toilets!”

“Our own toilets!” Salima shouted, and the little one said something that was almost toilets and that set them both to laughing like drains, laughing until tears streamed down their faces, and the kid laughed with them.

The coats arrived after dinner that night, too.

Salima and Nadifa clubbed together to rent a van the day they moved out, and they filled it to the ceiling with the detritus of Nadifa’s years and Salima’s months at the shelter—kids’ toys, clothes, shampoo bottles with enough left inside for three more careful washes, drawings, picture books, scrap paper for drawing and paper dolls painstakingly cut out of old printouts from the kiosk. The car inched its way through the Boston traffic, which they could only glimpse intermittently through the tiny bits of windshield that weren’t covered in shopping bags full of possessions.

The van pulled into Dorchester Towers’ back alley two hours later. It was a hot June day and the kids had needed two toilet breaks and several water breaks, which had blown up their plans to beat rush hour traffic, landing them squarely within it. But the two women were stoic. They had been on journeys that were much, much longer and far, far more difficult.

The poor-doors for Dorchester Towers weren’t finished yet, and so they had to go through a temporary plywood tunnel to enter the building. The lobby was in the same condition as the doors—raw drywall, open electrical receptacles, rough concrete floor with troughs cast into it for conduit. They lugged their things into the lobby in stages, leaving Nadifa’s eldest to stand guard and watch the kids as they went back and forth to the van, trying to get everything out before the sixty-minute mark, when they’d be billed for another hour’s rental. They squeaked in.

There in the lobby, sweating and humid, they met the Dorchester Towers elevators. The touchscreen asked you for your floor, then tracked the passage of the cars up and down the shafts. Cars would touch down in the lobby and they’d hear the doors on the other side sigh open and shut, but the doors facing them never opened.

They debated what to do. Eventually, they decided that the doors on this side must not be working at all, that it was yet another thing that had to be completed, along with the lobby and the doors and please god, air conditioning.

Kids, belongings, themselves—somehow they got them out of the doors again, down the alley and around the building’s circumference to its lobby doors, which, they couldn’t help but notice, were finished, chromed, shined, smudge-free, and guarded.

The guard on the other side of the door buzzed the intercom when they tried the handle. He was white and wearing a semi-cop outfit, some kind of private security, which was unusual because that was the kind of job you saw brown people in, most of the time. They noticed this, too.

“Yes?”

“We live here, we’re moving in today. On the…” Salima waved down the road. “On the other side? But the elevators aren’t working there yet. We can take the stairs, after we move in, but she’s on the forty-second floor, and I’m on the thirty-fifth, and we have all this—” The pile of bags and clothes and drawings and children and themselves, all so disreputable, especially contrasted against the shining chrome, the unsmudged glass, which now had two of Nadifa’s kids’ faces and hands smearing slowly across it. Oops.

The security guard tapped his screen. “Elevators are working.”

“Not on that side. The elevators came down, but the doors didn’t open.”

“Step aside please.” He said it so sharply that even Nadifa’s kids snapped to attention. There were some people trying to get in, pressing their thumbs to a matte place on the doorframe that didn’t smudge. The doors gasped open and let out a blessed gust of air conditioning that almost brought them to their knees. The beaded sweat on their backs and legs and faces and scalps spilled as much of their heat as it could in the brief wind. Then the fine people were through the door, not having looked once at them. They were preppy, a look Salima had come to understand since moving to this city of colleges and universities, with floppy blond hair and carefully scuffed tennis outfits and sweaty, shining faces. The security guard greeted them and chatted with them, words inaudible through the closed doors. They were amiable enough, and waved good-bye as they stepped into the elevator. As the doors closed, Salima saw the doors on the opposite side, the doors that opened into that other lobby.

The security guard gave them an irritated look and shook his head like he couldn’t believe they were still hanging around, blocking his doorway. “Your entrance is around back.”

“The elevators don’t work,” Salima reminded him. “We waited and waited—”

“The elevators work. They just give priority to the market-rent side. You’ll get an elevator when none of these folks need one.”

Salima grasped the system and its logic in an instant. The only reason she’d been able to rent in this building was that the developer had to promise that they’d make some low-income housing available in exchange for permission to build fifty stories instead of the thirty that the other buildings in the neighborhood rose to. There was a lot of this sort of thing, and she knew that there were rules about the low-income units, what the landlords had to provide and what she was forbidden from doing.

But now she saw an important truth: even the pettiest amenity would be spitefully denied to the subsidy apartments unless the landlord was forced by law to provide it. She had spent enough time as Auntie Salima, helping to raise Nadifa’s three kids, to recognize the logic of a mulish child who wanted to make their displeasure known.

“Come on,” she said, as she picked up a double armload of bags and slogged back around the building to the poor-door.

The apartment was wonderful. The promised luxury of a private shower and a bathtub she could lie down in if she squinched her legs and put her chin on her chest (but it was her bathtub!) and a single bed with a good mattress that no one else had ever slept upon, and when she folded that up, she could fold down the sofa slab with its bright cushions. Raise that slab up a little higher and twist the coffee table so that its legs extended and it became a dining table and you could seat three, or four if they were all very good friends. The walls had good insulation, and what little sound leaked in from the units around her was inaudible so long as she ran the fan in the HVAC at the lowest setting, something she could automate with the apartment’s sensors so it just happened whenever she was home.

The kitchen had “all major appliances,” just as advertised: the toaster, the dishwasher—a small thing that would hold all the dishes from a meal for one, along with a mixing bowl or one of the toaster’s baking pans—the fridge. They all started working once she’d input her debit-card number, and they presented her with menus of approved consumables: the dishes that would work in the dishwasher, the range of food that would work with the toaster, from bread to ready-meals. The washing machine would do a towel and sheets, or two days’ clothes, and there were dozens of compatible detergents she could order from its screen. The prices all included delivery, or she could shop for herself in approved stores, but there was always the risk that she’d pick up something that was incompatible with her model, so it would be better for everyone concerned if she’d do her shopping right there in her kitchen, where it was most convenient for everyone.

It was only a short walk to the T, and the stairs weren’t that bad going down in the morning. Coming back up was another story: thirty-five floors was seventy flights of stairs. She braved them about once a week and told herself that she was making herself healthy with such an intense aerobic workout.

Having a place to live that was truly hers made a huge difference in her life. Something about the stability, the confidence—hell, just having a reliable place to do laundry every night—it all added up to the sense that she was finally exiting the endless limbo she’d lived in all her life. Her earliest memories were of being on the move with her parents, one camp and then another, then an uncle’s house for a while, then another camp, then temporary apartments, then the crossing to America, the camp, the shelter. All that time, she’d had the sense that her life was on hold, that she was floating around like a leaf in the breeze, sometimes snagged on a branch and sometimes lofted up to the clouds, but never touching down, never coming to rest. It meant that she never really thought about her life more than a few days in advance. Now, in her own home, she was thinking about what her future held.

Some combination of luck and self-confidence was with her, and within a month she’d landed a full-time job as a bookkeeper for a company that serviced little mom-and-pop shops. She had half a dozen clients and she’d try to see each of them once a week, even if she could have done most of the work from home. She preferred setting up in the back room of a dry cleaner or a convenience store or a little ice-cream parlor and going over the logs from the registers and the invoices, scheduling payments and chatting with the staff and the owners. She learned that people liked to be warned of impending cash-flow crunches and other potential snags she could see in their books and within a few months she was more like a trusted advisor than a contractor. She remembered their birthdays and brought them cards, and then when her twenty-fifth rolled around, the owner of a vintage clothing store surprised her with a gorgeous Japanese satin jacket from the previous century, the back embroidered with a tiger that had faded beautifully over the years, with a patina like a Persian rug.

Nadifa’s kids got into school and Nadifa even started to fill in; the breathing room of time to herself meant that she could get a decent meal, could take care of her hair and clothes. She’d always had a regal bearing, but it warred with a natural overburdened-mother’s shoulder-slump, the exhaustion lines, the hands always full of kids or toys or laundry, the stains on her beautifully tailored clothes. With some stability in her life, Nadifa’s underlying nature asserted itself. Her clothes were impeccable, the lines in her face made her look serious, and then when she’d crack a wicked joke and her eye would gleam, the contrast between the seriousness and the humor was like something you’d see in an old painting.

Nadifa’s kids never lost their mischief, but school was good for them, gave them some structure to work within and fight against. They were behind, especially Abdirahim, the eldest at twelve, and Nadifa rode his ass, making him work through his remedial homework assignments on his phone or even the big screen in their living room provided the littlies could be tamped down to mere chaos. Nadifa’s place had two rooms, one for the kids and the living room, which was exactly like Salima’s, turning into a bedroom by folding down the table and folding up the sofa and folding down the bed, a magic trick that had to be done in the right order or everything snagged everything else in the middle of the room in an unholy knot that had to be carefully worked to loosen it.

Things were good, until the appliances started to disobey her.

Your scientists were so preoccupied with whether or not they could, they didn ‘t stop to think if they should. #IoT

Credit: Werayuth Tessrimuang / EyeEm / Getty Images

Your scientists were so preoccupied with whether or not they could, they didn ‘t stop to think if they should. #IoT Credit: Werayuth Tessrimuang / EyeEm / Getty Images

She did the washing machine just because she could. Once you had a kitchen full of devices that would obey you, the one that wouldn’t loomed ever larger and grew less and less tolerable. Besides, she was single, had no interest in swiping right on randos who never failed to disappoint. She had become an obsessive watcher of jailbreaking videos, especially since she’d followed a breadcrumb trail of ever-more daring videos, until she found the one that told her how to download the darknet tools that would get her to the real-deal sites where you could download new firmware images, swap tips and complaints, and jolly along with thousands of lawless anarchists like herself who were toasting any damned thing they felt like.

The washing machine was the hardest yet and involved uncoupling a lot of water hoses. She kept messing up the ring clamps, which she’d never had to use before, but she bore down on it with a bookkeeper’s resolve, methodically trying one variation after another, keeping a pan beneath the join to catch the leaks when she tested it out by turning on the water. While she worked, she switched to bread-making videos because that was her new passion, and now every time she saw Nadifa’s kids they begged her for whatever her latest creation was. She was making braided loaves now, an egg bread called challa, basting the rising dough with egg whites to give the crust a high gloss.

A week later, she made two important discoveries: first, shopping for detergent in the grocery store was a lot cheaper than buying it through her machine’s screen, and second, that her persistent eczema was actually an allergic reaction to something in the authorized laundry soap. Spring was springing and she’d been dreading sweating out the hot days in long sleeves to cover her flaking, itchy arms. She bought three vintage short-sleeved blouses and asked Nadifa to alter them to fit her as beautifully as all of Nadifa’s clothes.

She stopped short of jailbreaking her thermostat. For now. The thermostat was integrated with the building’s sensor grid, including the camera over her door, the cameras sprinkled around her apartment. It recognized her even before she entered, and spun the HVAC system up to speed before she’d even closed the door behind her, giving her just a moment of the claustrophobic, gasping air of the shut-up apartment before the white noise of the fan whisked a soft air current around and around. What’s more, it would watch her place while she was out at work and send her a video stream if it detected anyone in her place when she wasn’t there. She liked that, it comforted her. She’d been robbed twice in the shelter in Arizona, and had gotten used to carrying everything she owned of any value with her at all times. It was such a relief to be able to amass more valuable goods than she could easily carry.

The elevator was another matter.

When she’d moved into Dorchester Towers, the building had only been in service for a few weeks and was at less than half occupancy. As the apartments had filled up, the number of market-rate people using the elevators had increased to the point where it could take a full forty-five minutes to get a ride up to the thirty-fifth floor, and when the elevator finally came for the poor-door’s lobby, there were so many people waiting that she’d end up riding in a squash of people, face in someone’s sweaty armpit, and if she was lucky she’d be pressed against a wall behind her and not up against some strange man. She was nearly certain that the times it had seemed like she was being creeped on it had been an accident of the press of bodies and not actually creepiness, but she couldn’t be sure, and anyway, it still felt creepy.

One day she was sitting in Nadifa’s living room, drinking tea and watching Nadifa’s eldest do his extra homework. She and Nadifa had been complaining about the elevators for a good twenty minutes—it was a well-established subject among all the subsidy tenants and they could really work themselves up about it—when Abdirahim, Nadifa’s eldest son, looked up from his math.

“Mama, why don’t we just use elevator captains?”

“Do your homework.” Nadifa operated on pure reflex when it came to her kids and homework, but after a moment she added, “What’s an elevator captain?”

Abdirahim’s smile was luminous. “It is so cool. If you’re the first person in the elevator in Japan, you’re the elevator captain. You have to hold the door-open button until everyone boards, and then you have to press the door-close button and all the floor buttons. If the elevator captain gets out before the elevator is empty, the next closest person has to do it.”

“Where do you hear this?”

“We did a unit on unspoken rules in social studies. I’m doing an extra-credit on the unspoken rules of refugee detention in America. The teacher loves that, she gets all solemn when I talk about it. The other refugee kids think it’s hilarious.”

“I don’t think it’s hilarious.” Nadifa was deadpan. “I think it’s very respectful.” She turned back to Salima, opened her mouth to start talking again, and then turned back to Abdirahim. “Why would we use an elevator captain?”

His smile was twice as big. “We could just take turns staying in the elevator in the morning and the afternoon, during the busy times. It won’t stop for a poor if there’s a rich who needs it, sure, but if there’s a poor in it, it won’t stop for a rich until the poor is out.”

Nadifa mouthed a poor to Salima and rolled her eyes. Salima covered her smile. The kids knew what was what and they told it like it was. Meanwhile the plan was dawning on Salima and Nadifa. It was weirdly elegant: simple, so there weren’t many things that could go wrong. Plus, it used the fact that the rich people didn’t want to have to ever see one of them used against them.

“Do your homework.” Nadifa used her stern voice, but her smile to Salima was the twin of Abdirahim’s. Salima mouthed smart kid and Nadifa nodded.

The two weeks of the elevator captains were the best in the building’s short history. From 7:30 to 8:45 in the morning and 5:15 to 6:30 at night, there was effectively one elevator exclusively reserved for the use of the poor side of the building, serving the ten floors out of fifty-six. That left fifteen elevators for the rich people to use, and so at first they may not have even noticed that their unseen neighbors living in their building’s off-limits spaces were getting up and down in a matter of minutes, rather than waiting an hour or trudging the stairs.

But someone figured it out. Nadifa called Salima at work, using anger to mask her worry. “They were waiting in the lobby. Three security guards! Three! And of course it had to be Abdirahim who was elevator captain.” It was Abdirahim’s idea and he was the most enthusiastic captain in the building. Salima had even bought him a little peaked military cap from her vintage store client’s stock, and he wore it at a jaunty angle during his shifts, looking almost indecently cute.

He’d just brought the elevator back down to the ground floor and was mashing the close-door button with the lightning reflexes of a thirteen-year-old raised on video games when the other door opened, the rich-person door, the door that never, ever opened while any of them were in the car.

The three security guards demanded Abdirahim’s name and papers—and when he told them that they were in his home, on the forty-second floor, they refused to let him go get them. Instead, they took him down into the basement, using their security-guard fobs to override the elevator’s controls. They locked him in a windowless room with a reinforced door and conspicuous cameras in each ceiling corner and slammed the door on him.

After a long time, they came in to question him. He knew that he was late getting home and that his mum would be getting worried, though not frantic, because Nadifa didn’t do frantic. Furious, yes. Frantic, never. Furious was a lot more worrying, honestly. That was the thought that was in his head when he explained the whole elevator captain business to the security guards, who questioned him and denied him water or the use of the toilet until it seemed that every drop of water in his body was in his bladder and trying desperately to escape.

They went over the story again and again, and he began to cry, because it reminded him of the questioning they’d had in the camps, when he was tiny, and again when they got to America, when he was small. Those had been hard times, with his father dying and refusing to show it, sitting up ramrod straight and answering question after question, praying they wouldn’t detect his illness and use it as an excuse to turn away the family.

The memory of that time overcame him and he sobbed and couldn’t answer their questions anymore, and that’s when they called Nadifa, finally, and she was furious, but not at him; she yelled at them about re-traumatizing a child and demanded their names and their badge numbers and even got out her phone and recorded it all, even him crying, which made him ashamed, but still, he couldn’t stop.

There would be a reckoning, Nadifa swore, and Salima thought she was probably right, but that they would get the worst of it.

They did.

The elevators had cameras in them, of course, and it took the face-recognition software all of ten seconds to produce a list of all the poor-door residents who’d used the elevator captain system, with times and dates of each ride. It took a day for the building management to merge those records with form letters informing everyone who’d participated that they were in violation of their lease, which forbade “tampering with, reverse engineering, disabling, bypassing, disconnecting, spoofing, undermining, damaging, or subverting” any of the building’s systems. Further violations would result in eviction proceedings. Be warned. Be told.

It was humiliating to be addressed in this manner. Even for Salima, who had been subjected to the most humiliating of depredations over the years—strip searches and confiscations, collective punishments, and scouring of her most private data and memories to find an excuse to deny her humanity—it burned. After years of spinning in place, she had finally started her life in earnest, with a place and a job and friends who were nearly family. This was a reminder that her current life was a tissue-thin surface covering the world she’d lived in before.

For her whole life, the world had been divided into the people around her, people who knew her, and who she was. Most of those were people who wished her well and supported her and she supported them back. Some of those people were bad people and meant her harm—the camps were not paradise—but even for them, it was personal.

But there was another world, vast beyond her knowing, of people who didn’t know her at all, but who held her life in their hands. The ones who thronged in demonstrations against refugees. The politicians who raged about the scourge of terrorists hidden among refugees, and the ones who talked in code about “assimilation” and “too much, too fast.” The soldiers and cops and guards who pointed guns at her, barked orders at her. The bureaucrats she never saw who rejected her paperwork for cryptic reasons she could only guess at, and the bureaucrats who looked her in the eye and rejected her paperwork and refused to explain themselves.

Now there was a new group in that latter class, distant as the causes of the weather: the building management company and its laser printer, blasting out eviction threats to people whose names they didn’t know and whose faces they’d never seen over transgressions so petty and rules so demeaning.

The elevator captains had been a good chuckle, a way for everyone from the poor-doors and the poor-floors to feel like they were mice outsmarting the cats. The letters put them in their place: roaches, facing exterminators.

Someone’s always watching, eh? Credit: Susie Adams / Getty Images

The elevators weren’t any better programmed than the Disher or the Boulangism or the thermostat or anything else, really. The big difference was access. She could take her Disher to pieces in her kitchen without having to explain herself to anyone, but let her try that in the hallway, in sight of the cameras and her neighbors, and the situation would be very different.

To take out the elevators, she’d need to take out the cameras, and then work in the very small hours, and still she would risk discovery, so she’d need a disguise, a maintenance outfit, and maybe she could also take out the lights and replace them with working lights—she began to visualize the tableau: her down on one knee in shapeless coveralls with a hard hat pulled way down, the lights out and illumination from floodlights that would shine right into the eyes of anyone who tried to snoop. It was a fun daydream, and she enjoyed the game of thinking of how someone might catch her and how she might avoid being caught. It was an especially good way to recover from the exhaustion of trudging thirty-five flights up, or the frustration of waiting for forty-five minutes with a cooling pot of tagine from the corner deli in her hand, the smell driving her crazy.

She pushed around the wreckage of her tagine with a glass of cheap and delicious retsina—a favorite among so many refugees who’d made the passage through Greece, and now a staple of refugees who hadn’t, thanks to its popularity in the camps—and looked out her tiny window at Boston far below her, the Charles swollen to its levees, the ant-like people swarming home under the streetlights as autumn’s early night fell swiftly upon them. She daydreamed about hi-viz and work lights, about the tools she’d use to remove the firefighter’s override panel to reveal the USB port beneath, the subtle ways in which she would alter the building’s algorithms so that the faceless people would never discover her intrusion.

There was a ding at the door and the screen showed her Abdirahim, weirdly distorted by the camera’s autofocus on his face, which was a good foot below the adult-height camera mounting. She waved the door unlocked and he let himself in, looking from her to the tagine to the wine and then back to her.

“Have you eaten?” It was a phrase she remembered her mother saying to everyone who came through their door, even when there was no food to share. It had irritated her once, and now she said it automatically on those rare occasions when someone came through her door.

“Yes.” Abdirahim said it too quickly.

“But you’re still hungry.” It wasn’t a question. She remembered being a thirteen-year-old: hungry all the time. She got him a plate and spooned some tagine onto it and then found a pita and popped it in her toaster to warm it. When it was done, he looked at her with wide eyes.

“Yours works?”

It took a moment for her to figure out what he meant. The toaster. “It works,” she said. “I fixed it.” Then, with a little pride: “The dishwasher, too. And the thermostat. And the fridge.”

“Show me.”

“Eat first.”

The food barely touched his throat on the way down. She felt like she should probably make him eat slowly in her capacity in loco parentis, but she was as eager to show him as he was to be shown. When he said show me it made her realize that she’d been bursting with secret knowledge that she’d wanted more than anything to share.

When he was done, she put his dishes in the dishwasher and gestured him over to her so that she could show him the boot screen as she put the Disher through its paces, with the fanciful graphics she’d installed, of anthropomorphic dishes with bad attitudes showering angrily in the trademark Disher spray. He clapped and laughed and demanded to see the rest, and then to be shown how to do it.

They say you don’t really know how to do something until you can teach it to someone else. As Salima looked up the instructions again, she realized how much of it had just been recipe-following the first time around and how much she’d come to understand since, so that the steps made sense. She was able to explain to Abdirahim the why of each step, nearly as much as the what and how, and her heart beat and her blood sang with the experience of mastery.

This was the antidote, she realized, to the feeling of distant people whom she’d never meet who held the power of everything over her. To be able to control the computers around her, rather than being controlled by them.

“You see,” she said at last, as a realization came out of the blue to her and left her wonderstruck and thunderstruck, feeling like a revelating prophet. “You see, if someone wants to control you with a computer, they have to put the computer where you are, and they are not, and so you can access that computer without supervision. A computer you can access without supervision is a computer you can change, because all these computers are the same, deep down. When you get down to the programs underneath the skin, a toaster and a dishwasher and a thermostat, they’re all the same computer in different cases. Once you can seize control over that computer, all of them are yours.”

As the words left her mouth, her messianic fervor was replaced by nagging self doubt, the knowledge that she was shouting triumphantly at a small boy who had only gotten out of temporary refugee housing a few months before, and she felt foolish and small. But then she saw the gleam in Abdirahim’s eyes, and it was the same as the gleam in her eyes, and she knew that the two of them were sharing the vision.

“Our dishwasher and cooker haven’t worked in weeks,” he said.

“Oh, dear.” She hadn’t even thought of that. She had reflexively kept her work a secret from Nadifa, because she was doing something potentially dangerous and she didn’t want Nadifa to point this out. But that was before her vision. “We should do something about that.” She held out her hand. “Let’s go see your mother.” She remembered to take the retsina with her on her way out the door.

Perhaps Nadifa would have been upset at the idea of hacking the family’s appliances, but that was before she had spent two weeks parenting without a toaster or dishwasher. The hardship of eating everything cold or shelling out money she didn’t have for takeaways had softened any concerns she might have had, and as she watched Abdirahim show his sisters how to jailbreak all the apartment’s major appliances, she radiated motherly pride.

“He’s good at it,” Salima said. “I only showed him once and now—” She gestured.

“Do you think we’ll get in trouble? With the building, I mean? They own the appliances.”

Salima shrugged. “They were getting a share of the money we spent before, for the special bread and soap and so on. But with both companies bankrupt, they won’t be expecting any new money. Now, if the companies do ever come back from bankruptcy and still no one here is using their products…”

Nadifa nodded. “That would definitely be trouble.” She watched her kids, who had the cover off the thermostat and were avidly watching a video on the big screen next to it, where a person whose body had been mapped to a giant animated rabbit was explaining how to get it to fall back into a debug mode from which it would accept commands that let you override central commands to it. “But if it’s just the two of us, will they even find out?”

Salima shrugged again. “If the system is designed well, then yes. It would be very weird for our apartments to generate much lower revenues than any of the others. I once did a job where I saw that two of the self-checkouts at a pharmacy were generating twenty percent less money than the rest. At first I thought it was that they were broken, but even when they were serviced and even moved, they were always twenty percent down from the average. They got sent away for analysis and they’d been hacked and were being skimmed.”

“But you are good at your job, and you care about that sort of thing.” Unspoken: no one good at their job, who cared about anything, was involved in the poor-floors of Dorchester Towers.

“I’m sure they care about money. But perhaps they’re not so well designed.” She pondered it. “I don’t know. They certainly care a lot about making money, so the parts that help them make as much money would probably have the most attention. I’ll search for it. There must be other people in this situation.”

The kids successfully tested their modifications to the thermostat and closed it up, looking this way and that for something else to attack.

“Don’t forget the refrigerator,” Nadifa said. “That’s a fun one. Very tricky.”

They raced to the screen and started typing, sending Idil, the eldest girl, to read the model number off the label on the inside of the fridge door.

Salima knew that the kids wouldn’t stop at their own apartments, of course. She’d pass them in the hallways, sometimes, rushing from one apartment to the next. The feeling this gave her was hard to pin down: pride and excitement, but also trepidation and a sick, impotent sensation, the echo of the slow roll her stomach had done when she came home to find that laser-printed threat stuck to her door, to all their doors.

On the elevators, Salima heard whispers: Have you done your place yet? It’s so easy. I’m baking bread again! We found some beautiful dishes at a thrift shop, such a treat to be able to wash them in the machine. My little boy did it so easy!

Then one night, a knock at her door, urgent and low. She opened it and found Abdirahim, wide-eyed and stressed, and her pulse quickened, her armpits slickened, and she thought, Oh no, this is it.

“Tell me,” she said, bringing him in.

“I did the same as always,” he said. “A toaster. I’ve done so many of them. But something went wrong and now it won’t even turn on.”

She whooshed out a sigh of relief. He’d bricked some poor person’s toaster, but he hadn’t gotten them all evicted. “Let’s go see.”

There were message boards for this eventuality, of course. Abdirahim wasn’t the first person to brick an appliance. There were tricks to get it to boot into an emergency shell from which the original factory operating system could be laboriously reinstalled, and then they could start over. She used Abdirahim as her helper, reading her instructions and searching for help when they got unexpected error messages.

The toaster’s owner was an old Serbian man, who’d never spoken a word to her, though they’d shared elevators and waited in the lobby together often enough. She had assumed that he was a racist, because that was usually the reason that white people didn’t speak to her. She didn’t take it personally. Some people were just ignorant.

But it seemed that he was painfully shy and awkward, and not (necessarily) racist. He offered them tea and served them biscuits he counted out carefully from a packet that he took from a nearly empty cupboard in which she spotted a huge jar of food-bank peanut butter and not much else. He excused himself to use the toilet four times while they worked, and she heard the painful dribble of an old man struggling with an enlarged prostate.

So frustrating when you can’t get the kitchen bootloader screens to load…

At one point, she was ready to give up. The toaster wouldn’t even show her a bootloader screen—it was in worse shape than when she’d started. But the old man looked so concerned, and she knew he wouldn’t be able to afford a new toaster—she imagined the cold meals of biscuits and peanut butter he’d been surviving on since Boulangism had shut down.

So she and Abdirahim went back to step one, checking everything, everything, very methodically. Finally, they noticed that the toaster was actually an earlier model than the ones that everyone else had in the building—cosmetically identical, but with a model number that was a single letter off, and when she searched on that, she found a completely different set of instructions, and these worked. It was after 1:00 A.M. when they finished, but she still went down to her place and came back up with the makings of grilled cheese sandwiches on homemade bread, and they had a midnight feast that gave her heartburn, but it was worth it.

The next time, it was a kid she didn’t even know, tapping at her door and asking for help with a bricked screen. Abdirahim had apparently told his army of Dorchester Towers Irregulars that she was a reliable source of level 2 emergency tech support.

The third time it happened, she realized she needed to get ahead of the phenomenon if she ever wanted to have another moment to herself.

“Abdirahim.” She stared intently at the kid until he met her eyes. Nadifa’s presence helped.

“Yes, Auntie?” He only called her that when he was in trouble. The rest of the time it was “Salima,” or, with learned American familiarity, “Sally,” which was a new one on her that she wasn’t entirely happy about.

“The way you are doing this, you and your friends, it’s dangerous. You’re going to get caught and you’re going to get the people who live here caught, too. Do you remember the elevator captains, and what happened?”

“Yes, Auntie.”

“We don’t want that again, do we?”

“No, Auntie.”

“We don’t want to get everyone here thrown out onto the streets, either.”

“No, Auntie.”

“So I want you to get all your friends to come to my place, tomorrow, after school. Five pm. Tell them, anyone who doesn’t come is not allowed to jailbreak anything ever again.”

He registered surprise. “You mean that if we come, we can still jailbreak?”

She smiled and met Nadifa’s eye. “Oh yes, my boy. We’re not going to stop breaking the rules. We’re just going to be smart about it.”

She bought snacks for the kids, more than she thought she’d need, but it wasn’t enough. They just kept coming, scratching at her door until she just propped it open, and still they came, cramming into her flat. Ten kids. Twenty. Forty. Then she lost count. They stood in the bathroom and passed around bags of sweets and pretzels, filled her kitchen and stood on the counter. One of them sat in her kitchen sink.

“Quiet please, quiet.” They shushed each other. She turned to Abdirahim. “Is this everyone?”

He made a show of craning his neck around the room, nodded. “I think so.”

She shook her head at him. “Close the door, please, and someone turn up the air conditioning?” The smell was that goaty, musky smell of many children at various stages of puberty in an enclosed space, a smell that brought her back to the kids’ dorms in the camps she’d lived in.

“I want to start by saying that I’m very proud of you all. You’ve taught yourselves some important skills, you know, and you’ve helped your neighbors when they needed it. But you know that what you’ve done—what I did, too—is against the rules, and now that it’s happening so often, it’s going to be harder and harder not to get caught. Getting caught is not an option. Can anyone tell me why?”

A forest of arms shot up and the smell buffeted her again. She pointed to a young girl, chubby, with a face full of clever mischief. “Because we’ll all get thrown out of the building?”

Salima nodded. “What else?”

The girl thought for a moment. “Also, everyone we’ve helped will get thrown out?”

Salima nodded again. “Very good.” It was good to hear that the kids knew the stakes. It was also scary to hear them uttered aloud, and scarier still to think of the level of recklessness the kids had exhibited, even though they’d understood those stakes.

“I’ve been researching this, because I don’t know any more about this than any of you. I learned by watching the same videos and reading the same message boards as you. But we’re not the only ones going through this and there’s been a lot of talk about it. The companies that made Disher and Boulangism have been bought up by new owners who say they’ll be back online soon, and so we need to figure out how to stay safe once that happens.”

She checked to see whether they were following all this. It was pretty esoteric, this idea of bankruptcies by distant companies. What did these kids think about the appliances they jailbroke? Did they see them as just weirdly nonfunctional gadgets they had to work around, like the bad touchscreens at the shelter? Or did they see them as the enemy, something that they were at war with, the weapons of a distant adversary who wanted to subjugate them to its will?

“The truth is that no one seems to know exactly how the companies will monitor what we do, especially after they have new owners. A lot of the original programmers were fired and some of them are on those same message boards, or at least they claim to be those original programmers, and there’s a real race on to see who can come up with a reliable way to trick the monitors into thinking that we haven’t been jailbreaking. We’re definitely going to have to change people’s appliances so that they generate some billings for the companies, because they’d notice if no money was coming from Dorchester Towers, right?” There was nodding. They were following along. They were bright kids, she thought, kids who’d spent their whole lives outsmarting gadgets that were designed to control them.

“Here’s the assignment: we’re going to read all those message boards and bring back what we find, figure out which people seem to know what they’re talking about, then we’re going to go back to every apartment and tweak all those appliances so that they’re safe.

“That’s assuming we come up with a decent plan. If we decide that no one knows what they’re talking about, we’re going to restore every appliance to its factory defaults, un-jailbreak everything.” That prompted groans and even a few cries of protest, but she held her hands up. “I know, I know. But better to have bad appliances than no home. There are millions of people around the world in the same situation as us, anyway, and they’re all trying to solve this problem, so perhaps it won’t be so hard as all that. I know that reading message boards isn’t as much fun as messing about with gadgets, but if you want to be able to keep jailbreaking, you’ll have to do the research, too.”

It was too crowded for much Q&A, but Abdirahim put his hand up anyway. She called on him. “Auntie, there’s one thing I can’t figure out.”

“Only one?” She smiled and he smiled back.

“For now. When I bring a notepad to school, I can write anything I want on it. I don’t need to ask the company that made the pen or the store that sold me the notebook how I can use it. I can tear out the pages and make paper airplanes, or doodle, or copy down what the teacher says. When I put on a pair of shoes, I can wear any socks I want. I can walk anywhere I want to go on my shoes. I can wipe myself with any sort of toilet paper—” That got a laugh. “But I can’t toast any bread I want in my toaster.”

She waited. He was struggling to find the words. “What’s the question, Abdirahim?”

He shook his head, shrugged. “I guess I don’t know. I just want to understand, how can it be against the law to choose your bread but not your socks? What makes a toaster different from shoes?”

She opened her mouth to answer, but discovered she didn’t know the answer. Right up until that moment she’d felt like she had some intuitive sense of which things were objects-with-rules and which ones were objects-without-rules, felt it so readily that she hadn’t even named the two categories until just that instant. Now that she tried to come up with a rule to explain the difference between the two, she found she couldn’t.

“That is an excellent question,” she said at last. “Why don’t you research the answer and tell us all what you find out.”

He rolled his eyes and let out a showy groan but he looked excited by the challenge. He really was a bright little fellow. She chased the kids out of her flat, buzzing with conversation, joking and shoving and posturing in the way of kids. The smell lingered after they were gone and she turned up the HVAC to 140 percent of its nominal capacity, a feature whose purpose had mystified her when she’d jailbroken the thermostat. But now she was thankful for it.

She tried to go to sleep, but Abdirahim’s question nagged at her, so she raised her bed until it was a sofa and worked on the big screen for a couple hours, discovering to her relief that reading about technology law was better than a sleeping pill.

“Unplug it,” feels like good universal advice. Credit: Dennis Lane / Getty Images

There was something about the woman standing over her on the T that snagged her attention. She wasn’t anyone Salima knew, but something about her seemed so familiar. She kept sneaking glances, and then it hit her: the logo on the woman’s ID badge, dangling from a lanyard at eye height. Salima knew that logo, though she hadn’t seen it in months: it was the Boulangism logo, a stylized slice of bread in a single continuous line, three squiggly heat lines radiating off it.

The woman caught her staring, and they made eye contact. She was young and white and had messy brown hair and those contacts the computer people wore to help them stare at screens all day without messing up their sleep schedules. The light from the ads lining the top third of the car cast a rainbow sheen over them.

“Boulangism?” Salima said.

The woman nodded enthusiastically. “That’s right.”

“They’re in Boston?”

“They are now. They got bought out by a fund on Route 128, and then they recruited a bunch of us MIT kids to bash them back into shape and get them stood up again.” The woman was younger than Salima had thought—an undergrad, or maybe a young grad student. Salima tried to picture the kids who crammed into her apartment as a classmate of this young woman, getting tempted away from their studies by a deep-pocketed company. They were smart, but were they smart enough? How smart did you have to be? She suddenly wanted to know more about the woman.

“Do you have a Boulangism?”

Salima nodded. “Do you?”

The woman snorted. “God, no. I mean, that business model, authorized bread? I wouldn’t put one of those in my house if you paid me. Why’d you buy one?”

“I didn’t. It came with the apartment.”

“Unplug it and put it in a closet. Get a real oven.”

This had literally never occurred to Salima. She had no idea how much a toaster oven cost. She could probably afford it. Not that she had any closet space. And then there were all the other people on the poor-floors, the old ones, the ones with kids, the ones who didn’t have her skills or who couldn’t speak English. She couldn’t buy ovens for all of them—let alone dishwashers and all the other appliances.

“You don’t seem to think much of them.”

The woman rolled her eyes. “It’s a good job, and the technical challenges are interesting. Hell, even the basic units do a good job, as far as that goes. But the lockdown is ob-nox-ious.”

Salima couldn’t help herself. “I think so, too.”

“They’ve brought in a whole team to find people who’re jailbreaking their units, a snitch squad. Now that’s a job I wouldn’t do. A girl’s gotta have standards.”

They’d gone past Salima’s stop. She didn’t care. She could always ride back the other way. The conversation was too good to end. “I’m Salima.”

“Wyoming,” the girl said, and shook. Her hands were slim and clever, typist’s hands.

Though they were in a very public place, Salima felt a bubble of inattention around them—that urban thing, where you pretended you couldn’t see the people pressed up against you. It was something she’d gotten good at in the camps, where there were so many times when the skill was necessary to keep her sanity.

“When do you think you’ll have the servers up again?” Salima said. The guy next to her stood to debark as they pulled into a station. How many more stops would they have? Salima thought she’d stay on one stop past Wyoming, get off and cross to the opposite platform and ride back. If she got off at the same stop, she’d seem like a creepy stalker.

Wyoming startled at the question. “Oh, shit! I didn’t even think of it. This must have sucked for you. How long has it been? Four months? Five? With no oven? You must be so sick of waiting for us, huh?”

“Five months,” Salima said. “It certainly has been a long time.”