Graphic adventures like Space Quest, Leisure Suit Larry, and Day of the …

Space Quest. Day of the Tentacle. Gabriel Knight. Monkey Island. To gamers of a certain age, the mere names evoke an entire world of gaming, now largely lost.

Graphic adventure games struggle to find success in today’s market, but once upon a time they topped sales charts year after year. The genre shot to the top of computer gaming in the latter half of the 1980s, then suffered an equally precipitous fall a decade later. It shaped the fate of the largest companies in the gaming industry even as the games’ crude color graphics served as the background for millions of childhood memories. It gave us Roger Wilco, Sam & Max, and the world of Myst. But few gamers today know the complete history of the genre, or how the classic Sierra and LucasArts titles of the late 1980s and early 1990s largely disappeared beneath the assault of first-person shooters.

Here’s how we got from King’s Quest to The Longest Journey and why it matters—and getting to the end of this particular story won’t require the use of a text parser, demand that you combine two inscrutable inventory objects to solve a demented puzzle, or send you pixel-hunting across the screen.

A picture’s worth a thousand words

The origins of the graphic adventure lie, unsurprisingly, in text adventures. Inspired by a version of Will Crowther’s Adventure, which was discovered by accident while remotely coding on a mainframe computer, husband and wife team Ken and Roberta Williams created Mystery House for the Apple II in 1980. Mystery House was a painfully simple text adventure that offered one big selling point: monochrome line drawings which accompanied the text. A second title, Wizard and the Princess, followed shortly after and added color graphics.

Wizard and the Princess was the first adventure game to support color graphics

These simple illustrations were enough to bring the games to life; even though the text parser was primitive, you could lose yourself in the game world, and people did. The games sold out everywhere that they were available. The couple was so encouraged by the success of their two games that they decided to switch the focus of their company, On-Line Systems, from consulting to game development. The graphic adventure was born, along with its most influential developer.

It wasn’t until 1983, though, that the genre received its first kick in the pants. IBM approached the fledging company, now renamed Sierra On-Line, with an offer of $700,000 to create a game that could show off the multimedia capabilities of the upcoming PCjr. And so was born the game that defined the genre, King’s Quest: Quest for the Crown, along with the scripting language Adventure Game Interpreter (AGI), which formed the backbone of Sierra’s adventure games until it was superseded in 1988.

The PCjr tanked, but King’s Quest took the computer gaming world by storm—being ported and remade for several other platforms and rapidly rising to bestseller status. It was the first computer game to support the 16 color EGA standard, and also the first to offer a pseudo-3D world in which players controlled a character—via a third-person perspective—who could move in front of, behind, or over other objects on the screen. Billed by some as an “interactive cartoon,” King’s Quest seemed to bring adventure games—and the fairy tales they used for inspiration—to life.

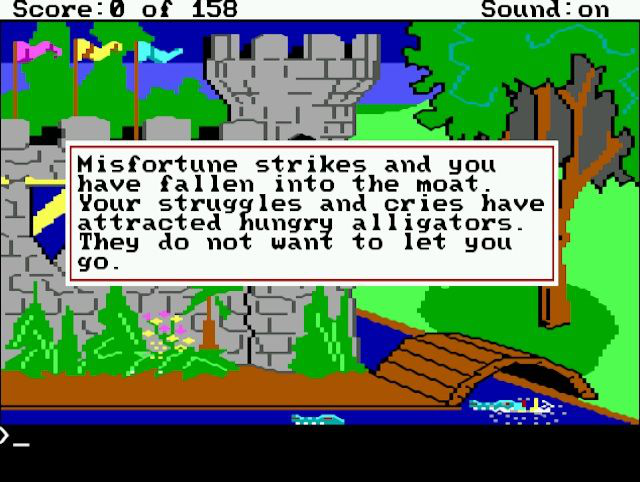

The first King’s Quest may have looked sweet and innocent, but even the first screen is fraught with danger

King’s Quest wasn’t perfect, though, and it suffered from a sometimes-convoluted logic and limited text parser. In some respects, the game was harder than its text-only brethren, since it omitted details that were clearly apparent on screen when responding to the “look” command. The issue of identifying the correct verb—long a problem in all adventures, text or graphic—was now joined by the problem of identifying the correct noun (when is a “rock” a “stone,” for instance?). Problems also existed with navigation. The illusion of a 3D space projected onto a 2D plane was just that, an illusion; orienting protagonist Graham with respect to a staircase, bridge, or cliff edge proved unintuitive and, in a game of frequent deaths, dangerous.

Enter the mouse

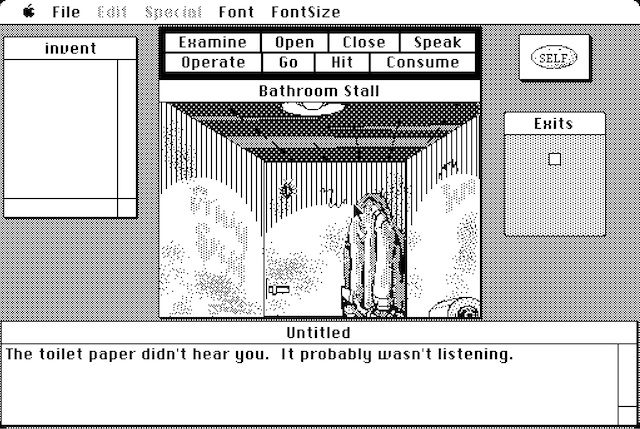

Sierra wasn’t the only company advancing the fledgling genre. Apple’s revolutionary Macintosh computer was released in January 1984, with a high-resolution display, graphical user interface, and a mouse as standard. It signaled a paradigm shift in computing, and a few clever developers saw an opportunity to extend the usability of the Mac to games. Silicon Beach Software released Enchanted Scepters, the first point-and-click adventure game, in 1984, with drop-down menus for selecting player actions and a text description displayed in a separate window from the static graphics. The real innovator, though, was ICOM Simulations, which released mystery-themed Déjà Vu the following year.

The first game in the MacVenture series, Déjà Vu offered a fully point-and-click interface. Separate windows displayed the (largely static) visual scene, the available exits, a second-person narration, and a tiered inventory system in which some objects could be stored within other objects. You could drag and drop objects around the scene and into your inventory. Other actions typically involved clicking on one of eight choices —Examine, Open, Close, Speak, Operate, Go, Hit, Consume—then clicking on an object in the scene or in your inventory. Often, double-clicking would act as a shortcut to either examine or open an object (whichever action seemed contextually more appropriate).

Early Macintosh point-and-click adventure Déjà Vu

Déjà Vu was an instant classic, thanks in large part to its snappy writing and sharp humor. It would soon be ported to several platforms, finding the most success on the NES, where the interface received major streamlining to handle a lower resolution and controller input. Other games followed in the MacVenture series, including Shadowgate and Uninvited, but none matched the popularity or prestige of Sierra’s Quest games. The no-typing, point-and-click concept would have to wait a little longer before it could become a genre standard.

In the meantime, Sierra forged ahead. Two King’s Quest sequels followed the first game, along with the first in a new Quest series, Space Quest, which added a comedic space opera to Sierra’s repertoire.

Lost in space

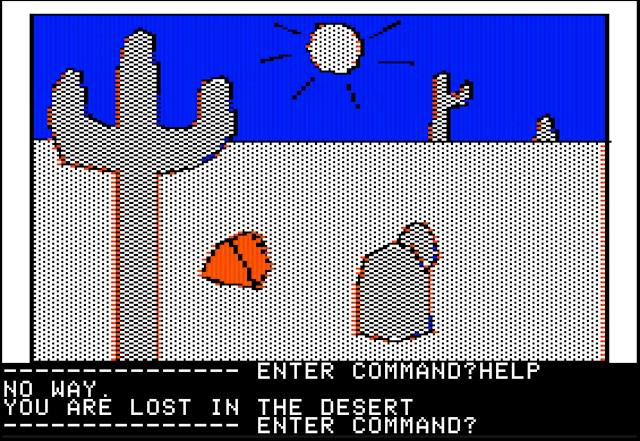

The goal of Space Quest: The Sarien Encounter was to recover the stolen “Star Generator” technology, but this was hardly serious sci-fi. The game cast the player as a hapless janitor who awakens from an on-duty broom closet nap to find his entire ship’s crew killed by an alien race. It took a more light-hearted approach than previous Sierra adventures, with every possible death being accompanied by a joke—usually at the player’s expense—and frequent references in narration to the fact that you were not just embodying the character on screen but also playing a game. Much of the joy came from uncovering the ways in which you could die, including one that memorably transported protagonist Roger Wilco to Daventry, the world of King’s Quest. Pop culture references also abounded, with the Blues Brothers and ZZ Top appearing in alien form at a bar in Ulence Flats.

Sierra’s beloved first foray into science fiction—Space Quest—quietly mocks you for being thorough

1987 brought a well-received Space Quest sequel, Vohaul’s Revenge, which continued the story of series protagonist Roger Wilco and introduced me to the Sierra adventure line. Fresh from his heroic exploits with the Sariens, Roger received a promotion to Head Janitor—a meaningless title, since he was the only janitor. As a child, I discovered the game some years after release and was immediately captivated by the detailed world that oozed humor from every orifice. You could get stuck to a tree (while attempting to climb it) or give a gigantic tentacled root-monster gastrointestinal problems digesting your body. It was gravity—not your would-be nemesis Sludge Vohaul—that proved to be your greatest adversary, mercilessly sucking you to the ground below, time and time again.

The suit makes the man

Two more cult favorites arrived the same year. Police Quest featured a story and gameplay mired in actual police procedure, with Sierra’s now-famous dry, black humor providing a comedic edge. But it was Leisure Suit Larry in the Land of the Lounge Lizards that made the greater impact. In 1986, company founder Ken Williams asked programmer Al Lowe to make an AGI version of Softporn, an earlier text adventure. Lowe kept Softporn’s puzzles, but introduced 38-year old lovable loser Larry Laffer as a new protagonist. A legend was born, as Larry’s misguided and pathetic attempts to have sex with every woman he meets led to dozens of bizarre and hilarious situations, as well as some comedically cruel deaths.

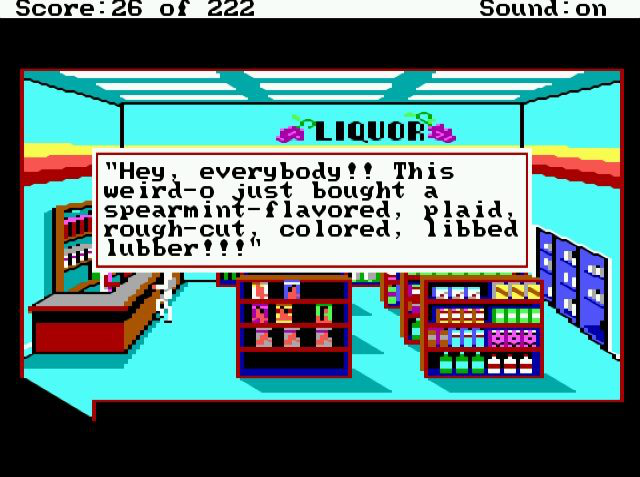

The infamous Leisure Suit Larry in the Land of the Lounge Lizards

For younger gamers such as myself, the age-gating quiz presented upon booting Larry was a game all of its own. If you told the game that you were above a certain age, it would dismiss you outright; otherwise, provided that you claimed to be over 18, you had to prove your age by answering a series of trivia questions relating to politics or pop culture. These questions made reaching the actual game seem like a kind of achievement; you earned the right to play. When you did manage to get inside, you were faced with a game that made few concessions in its mocking depravity. This was one of the few Sierra games that gained enjoyment from the presence of a text parser—the narrator had a witty response for a considerable number of ridiculous or dirty commands (including the random input of profanity).

Larry sold poorly, moving just 4,000 copies in its first month. But word of mouth spread quickly, and it became the third best-selling computer game in America in July 1988, just over a year after its initial release. Millions of pirated copies were played around the world, too. In one RetroGamer interview, Lowe remarked that a Russian computer consultant had told him Larry was so widespread in Russia that it seemed like it was a part of DOS.

No dying

Lucasfilm Games (which became LucasArts in 1990) entered the graphic adventure market in 1986, releasing Labyrinth: The Computer Game for just about all then-active home computer platforms. Labyrinth took inspiration from the Jim Henson film of the same name and used a slot machine text interface instead of the typical text parser. Players would choose a verb from the left slot and a noun from the right slot to select an action. It was the company’s second foray into the genre that really took off, however.

A programmer at Lucasfilm by the name of Ron Gilbert loved King’s Quest, but found fault in the frustrating text parser and frequent player deaths. He came up with the Script Creation Utility for Maniac Mansion (SCUMM), which powered the company’s second graphic adventure, Maniac Mansion. SCUMM took many of the best elements from Sierra’s AGI engine and ICOM’s MacVenture interface, with all verbs and inventory laid-out on the bottom of the screen while the scene was animated with moving characters.

Maniac Mansion—the first SCUMM game

Maniac Mansion offered multiple characters the player could switch between during the game, it featured multiple endings, and it had puzzles heavily dosed in humor. With art by Gary Winnick and a setting inspired by B-movie horror tales, the game had a distinctive look and feel, helped in large part by its refusal to take anything seriously. Although you could die in the game, unlike in later SCUMM titles, it took gross player error with each of your three selected characters.

Ron Gilbert pushed for a more player-friendly design philosophy, whereby players were not punished for curiosity and do not need to return to a much earlier point in the game when it becomes apparent they are missing a crucial item—the norm in prior adventure games. This emphasis on accessibility soon permeated the genre, opening it to new audiences. Maniac Mansion’s greatest legacy, though, was the SCUMM engine, which would be used to create thirteen original titles over the following decade.

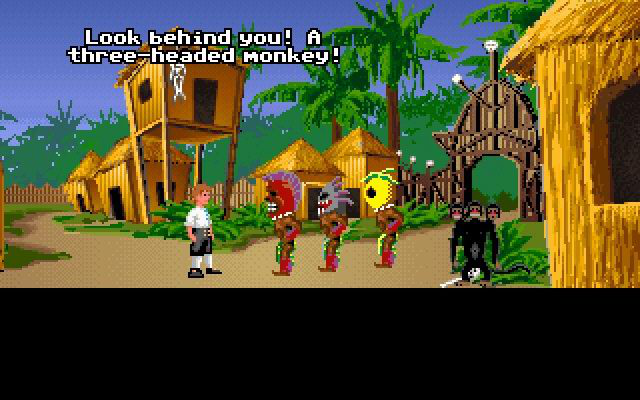

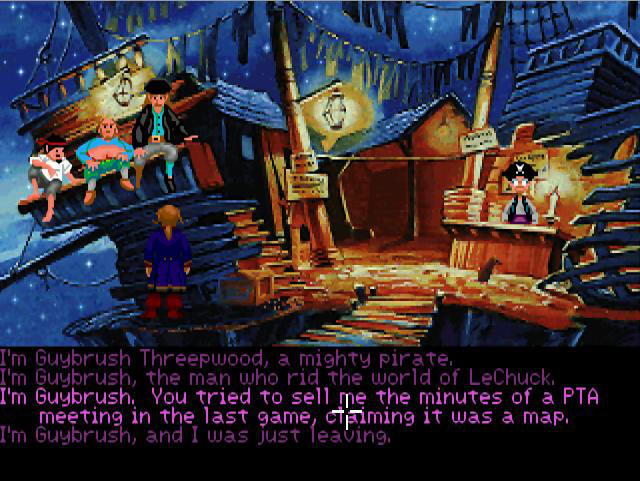

Zak McKracken and the Alien Mindbenders followed in 1988, with Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989) and Loom (1990) hot on its heels, before Tim Schafer and Dave Grossman partnered with Ron Gilbert to work on a swashbuckling pirate adventure called The Secret of Monkey Island. Wannabe pirate Guybrush Threepwood was first introduced here as LucasArts refined the player-friendly, comedic approach to adventure games. The game notably included dozens of in-jokes and stabs at adventure tropes, in addition to the much-loved Insult Swordfighting mini-game in which a series of insults and witty retorts are exchanged in lieu of actual swordfighting.

The three-headed monkey was a recurring gag in the Monkey Island games

Although Monkey Island lived up admirably to the SCUMM promise of accessibility, it featured some of the most bizarre puzzles of all time, including one that used a rubber chicken with a pulley in the middle and another that involved an actual red herring. The ridiculousness of the puzzles, much like its cast of quirky characters, became part of the game’s charm, as its internal logic was predicated upon silliness and clever wordplay.

Level up

Sierra replaced the AGI scripting language with SCI (Sierra’s Creative Interpreter) in 1988, with King’s Quest again used to demonstrate the latest technology. King’s Quest IV: The Perils of Rosella was notable also for being one of the earliest PC games to support sound cards (the AdLib Music Card and Roland MT-32) and for being released simultaneously in both AGI and SCI (AGI for the older systems; SCI for everything else).

King’s Quest IV: The Peril’s of Rosella marked a major upgrade in presentation for Sierra’s adventure games

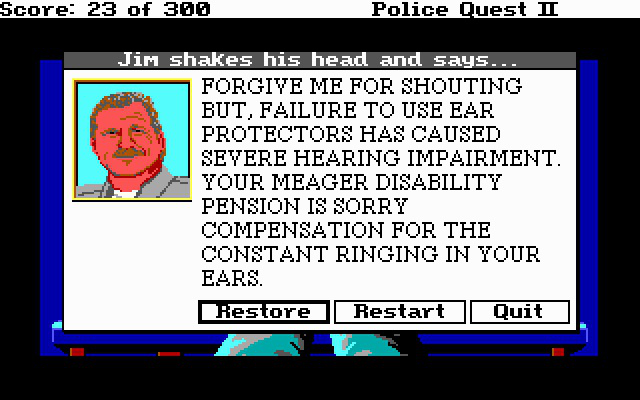

SCI’s big innovations were not the addition of a mouse-driven, icon-based interface as an alternative to the text-parser of earlier adventures, but rather its improved sound and graphics together with the switch to an object-oriented language that could run exactly the same on all platforms—years before Java. Gamers and critics alike were wowed by the capabilities of the new engine, which pushed ever-closer to the ideal of cinematic presentation. Older games were remade and re-released with high-resolution graphics and the new point-and-click interface, while new titles, such as Police Quest II, Space Quest III, and Hero’s Quest: So You Want to Be a Hero (an adventure-RPG hybrid), were tailor-made for the enhanced capabilities of the new engine.

Police Quest II protagonist Sonny Bonds learns the hard way that you should always wear ear protection at a gun range

Police Quest II: The Vengeance continued the story from the original Police Quest, with protagonist Sonny Bonds moving from patrol officer to homicide detective. By this point, it had become common for people to spend their playing time in Quest games searching for funny ways to die or to push the boundaries of the text parser. Police Quest games were heavily steeped in police protocol; if you didn’t strictly follow procedure, you died. I spent hours discovering the most interesting ways in which you could break with procedure: drawing a gun in public, yelling out to a suspect, revealing my identity while undercover, and trying to bribe or coerce colleagues are just a fraction of the things I tried to do (just to see what would happen). When you took the games seriously, though, Police Quest offered an insightful window into police life and the difficulty of catching criminals without breaking the law yourself.

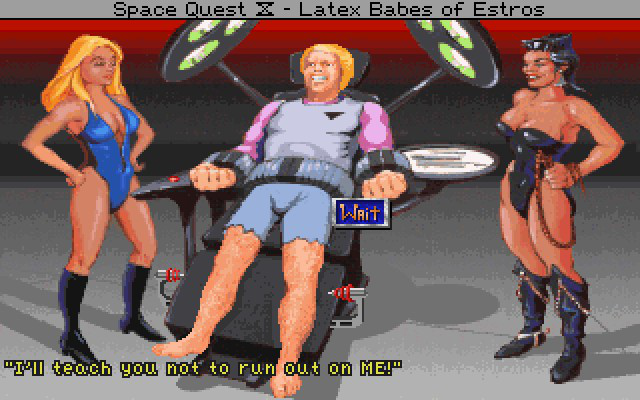

Sierra continued to improve the SCI engine throughout its life. As always, it was King’s Quest that showcased the big updates. King’s Quest V (1990) introduced the first major update, SCI1, which brought the aforementioned icon-based interface together with an upgrade to 256-color VGA graphics (the 1992 CD-ROM version also added full voice acting). Space Quest IV: Roger Wilco and the Time Rippers was perhaps the more impressive showcase of the new technology, however, with beautiful hand-painted graphics and a ridiculous story brimming with self-referentiality that sent Roger Wilco through a number fictional sequels (and also the original Space Quest).

The beautifully drawn, always ridiculous Space Quest IV

In 1991, LucasArts developed iMUSE—the Interactive Music Streaming Engine—as a new audio component of SCUMM. Composers Michael Land and Peter McConnell were behind the engine, which overcame many of the limitations of MIDI technology. Hard cuts and jarring music transitions were a thing of the past; SCUMM-powered adventures now had dynamic audio. This put the company at an immediate competitive advantage—none of its rivals had such a technology, which allowed far more interesting and subtle audio cues than ever before found in games. The new technology saw its first use in Monkey Island 2: LeChuck’s Revenge, which was SCUMM-creator Ron Gilbert’s last game with LucasArts (Gilbert left to found Humungous Entertainment with colleague Shelley Day).

Monkey Island 2 brought jokes new and old, improved upon the visuals of its predecessor, and introduced a new audio engine: iMUSE

The introduction of iMUSE made an immediate difference, too. Monkey Island 2 felt more full, more contiguous than any previous LucasArts game. The music seemed to respond spontaneously to your actions, no matter how unpredictable, which gave an impression that the arrangement was far more complex and expansive than it in fact was.

Hyperkinetic rabbity thing

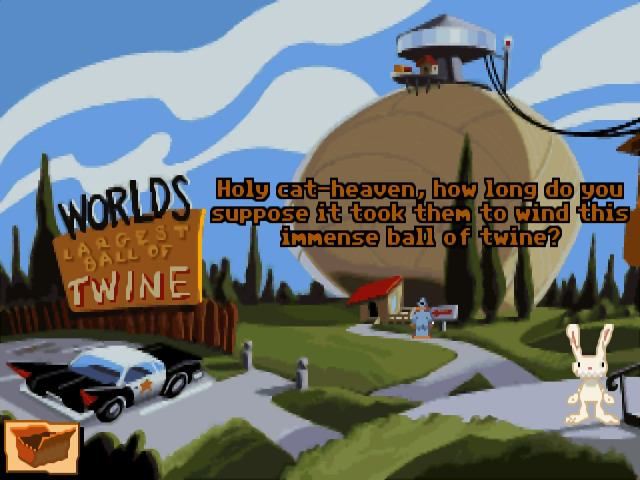

Perhaps the most memorable characters ever to appear in an adventure game, foul-mouthed freelance police Sam and Max made their debut in 1993 with Sam & Max Hit the Road. The game was significant for more than just beginning one of the most beloved adventure franchises; it brought visible changes to the SCUMM engine and was the first LucasArts adventure to be released after legendary designer Dave Grossman left the company. Day of the Tentacle, released earlier the same year, introduced changes on the backend that allowed for more detailed graphics. Sam & Max added a revamped user interface to this updated engine, with the list of verbs replaced by several cursor modes and the inventory moved to an off-screen menu.

Sam & Max wasn’t afraid to poke fun…at anything

Sam’s offbeat-but-keen observations and Max’s caustic wit, both of which were superbly voiced, were perfect for the almost-real present day setting, as the game poked fun at Americana in ways both subtle and overt. The pair have their money quite literally stashed in a rat hole, while their travels take them to a flooded mini-golf course enterprisingly converted into an alligator-infested driving range and a trip to the carnival subtly exposes common prejudices against misfits. Sam and Max also find exploitative tourist attractions such as a gigantic ball of twine and a small rock that utterly fails to look like a frog, and a country music star lives a life of absurdly extravagant self-indulgence that includes two gigantic statues and an escalator-equipped bed.

The dialogue selection menu featured only icons, so that jokes could not be read before being heard, while the script offered what are perhaps the strangest non-sequiturs ever to appear in a video game—take, for example, the time anthropomorphic dog Sam says (completely out of the blue), “My mind is a swirling miasma of scintillating thoughts and turgid ideas.”

Sam & Max‘s streamlined interface was a big step forward in character-driven graphic adventures—especially those made by LucasArts—as it allowed far more of the environment to be visible on-screen and made interaction more intuitive. But others—including, to some extent, Sierra with SCI—had beaten LucasArts to the punch. Dynamix put out Rise of the Dragon in 1990, followed by Heart of China and The Adventures of Willy Beamish in 1991, with minimal interface elements and a contextual cursor, which changed mode automatically depending on its position on the screen.

The Adventures of Willy Beamish—one of the few adventure games developed by Dynamix, which was bought by Sierra in 1990

Literary inspiration

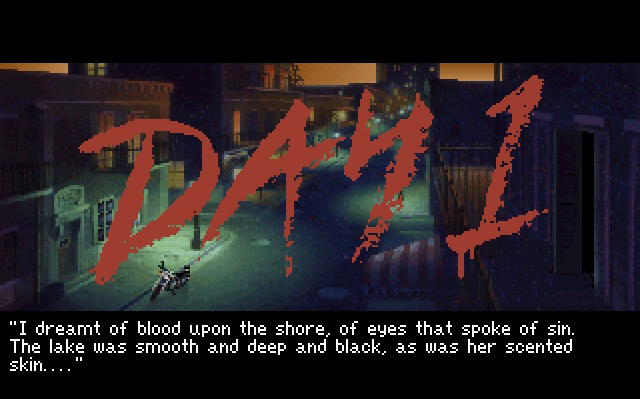

Sierra released what is widely regarded as one of the best-written games of all time in 1993. Gabriel Knight: Sins of the Fathers took a more literary approach than its forebears, with a deep story about a struggling novelist and a real-life murder-mystery. The game played like its contemporaries, but looked like a graphic novel brought to life—just as the original King’s Quest had given the impression of an interactive cartoon. 1994 cyberpunk hit Beneath a Steel Sky similarly pushed the storytelling potential of the genre, with an engaging plot set in a dystopian future version of Australia.

The mystery-novel plot of Gabriel Knight emerged rather more slowly than in other graphic adventures, but the pace never felt plodding, and its maturity belied the all-too-common sentiments of the time that games were exclusively for children. The game also notably used a custom interface that was unlike anything Sierra had produced before, with some actions—namely “use/execute” and “talk"—broken into multiple, slightly different actions—a strange move in a period of streamlined interfaces. The reception of this interface was mixed. On the one hand, it added more nuance to the player’s possible actions (such as the option to just chat rather than interrogate); on the other, it created needless redundancy.

The opening screen of Gabriel Knight

Trouble lurking in the Myst

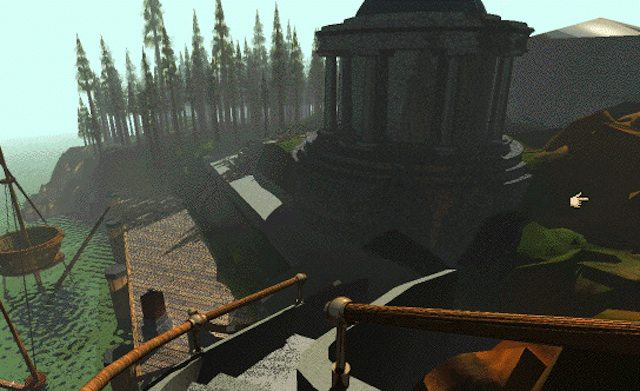

Cyan was already well-known on the Mac gaming scene when it began work on an ambitious new title that would utilize the emerging CD-ROM format. Leveraging Apple’s HyperCard authoring tool, The Manhole, Cosmic Osmo, and Spelunx had all been successful as exploratory adventure games aimed at a younger audience. Now the Miller brothers, who formed the core of Cyan, were ready to tackle a bigger project. The epic, surrealistic Myst was released for Mac in 1993, with purportedly photorealistic 3D graphics and a minimalistic point-and-click interface.

Myst dropped players on a deserted island full of strange contraptions, with no knowledge except what could be gathered from the environment. It was lauded for its mature story and atmospheric world, and it successfully integrated embedded QuickTime videos with the environment. Myst captured the imagination of its players and immersed them in its lavishly detailed—yet hauntingly empty—world. This (largely) never-before-seen mix of realistic and dreamlike world design made the game seem like such a leap forward that many overlooked its poor character development, limited interaction, and obtuse puzzle design.

We used to call that photorealistic

A Windows port soon followed as Myst quickly became the poster child of the computer games industry. It dominated sales charts, fast becoming the biggest selling computer game of all time (until The Sims came along), and with the help of The 7th Guest pushed the CD-ROM into widespread use—gone were the days of constantly switching between 14 floppy disks.

Unfortunately, the runaway success of Myst did more harm than good for the adventure genre. The bottom fell out of the market, and the weakest dragged the strong down with them, as dozens of horrible, broken clones—with far too little differentiation—flooded the adventure landscape, destroying consumer confidence and killing innovation as publishers pushed for “me too” graphics and puzzles. Cyan’s own Myst successor, Riven, expertly honed the formula to result in a much-improved experience when it was released in 1997. But it, too, spawned a multitude of copycats trying to make a quick buck.

Beacons of hope

Not all adventure games post-Myst were bad. The Journeyman Project trilogy, which actually began shortly before Myst was released, quickly emerged as a serious competitor to the Myst franchise. Over in Japan, where Déjà Vu had been a greater influence than in the West, Metal Gear Solid creator Hideo Kojima’s Blade Runner-esque Snatcher finally picked up an English version in 1994 (on the Sega CD). A series of Discworld games—based on fantasy author Terry Pratchett’s world of the same name—began in 1995, with acclaimed comic actor Eric Idle doing voice work.

I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream, as its fantastic title suggests, explored a twisted horror theme in an adaptation of a short story of the same name. In what is surely one of the most original adventure game concepts ever, Bad Mojo cast players as a human-turned-cockroach, who has a chance to save the life of a horrible-yet-sympathetic landlord in the process of finding a way to turn back into a human. The filthy apartment block took on a new scale from the perspective of a cockroach as you explored floors, walls, and furniture via direct-control and a third-person viewpoint to discover more than just a solution to your inconvenient bodily transformation.

Yes, really, you control the cockroach, and, no, that rat is not dead

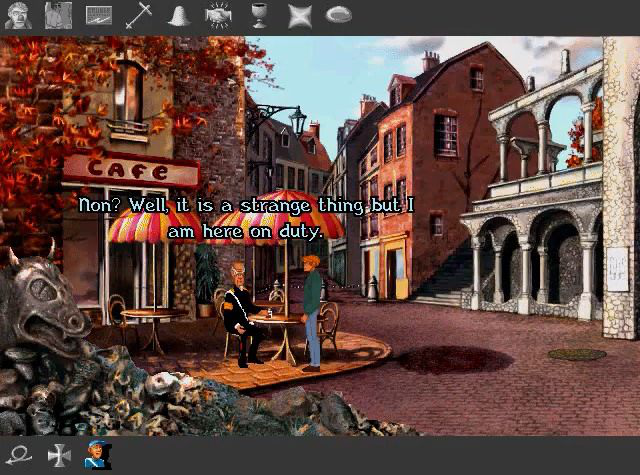

UK-based Revolution Software had made an impression in the early 90s with Lure of the Temptress and the award-winning Beneath a Steel Sky. On the eve of the genre’s precipitous decline, they followed up these early successes with the intelligently-written Broken Sword: Shadow of the Templars (originally subtitled Circle of Blood in the United States) and its sequel, The Smoking Mirror—both of which met resounding success.

The first Broken Sword followed the story of George Stobbart, an American tourist in Paris, who narrowly escapes a bomb attack on a café and witnesses a suspicious-looking clown (aren’t they all?) flee the scene. Unimpressed by the handling of the crime displayed by the local police, he decides to do some of his own investigation. What follows is a slow-paced but fascinating (and often humorous) tale of intrigue that is steeped in conspiracy theories and Knights Templar mythos, with a presentation that remains passable even by today’s standards.

The sedate but impressive Broken Sword

Controversial developments

Sierra met controversy by first replacing ex-California Highway Patrol officer Jim Walls with former LAPD chief Daryl F. Gates as designer for the fourth Police Quest installment, then, in 1995, releasing a non-adventure Police Quest and the horror-themed “interactive movie” Phantasmagoria. Reception of the high-budget Phantasmagoria was mixed, thanks to its excessive violence and other adult content—which resulted in the game being banned in Australia—and the ridiculous seven CDs needed to store the swathes of live-action video footage. But it still managed to be one of the best-selling games of the year.

FMV games were a horrible trend. Despite its success, Phantasmagoria was no exception

Looking back on Phantasmagoria now, you have to wonder how it sold so well. The stiff, cheesy visuals and horrendous production values have aged almost as badly as the clunky interface and limited interactivity, which seemed at a pitifully low resolution compared to the motion capture. Other FMV-based graphic adventures were released with a less jarring disconnect between the actors and their environments, the visuals, and the gameplay, including The X-Files Game (1998), Black Dahlia (1998), and The Beast Within: A Gabriel Knight Mystery (1995), but none could completely dispel the criticisms leveled at earlier FMV games.

Express train to nowhere

Jordan Mechner, the creator of late-80s hits Karateka and Prince of Persia, had spent much of the 1990s working on an adventure game. The Last Express was a revolutionary game set entirely on a train across Europe (the Orient Express) on the eve of World War I. It cast you as a fugitive taking on the identity of another passenger—a friend whom you find dead in his compartment after you arrive on the train via a moving motorcycle. It also featured a painstaking recreation of the original Orient Express, branching story paths, a novel rewind-time mechanic, a unique Art Nouveau visual style, and rotoscoped animation. What made The Last Express revolutionary, though, was its dialogue engine and tight, focused environment. It took place in accelerated real-time, with other characters acting independently of the player and with their own agendas—the world did not wait for you to act and continued unabated regardless of whether you were there to witness it.

Although the game counted the seconds, I lost all track of time when playing The Last Express. For the first time in a video game, I felt like I was in the world. I had to race from one end of the train to the other, desperate to know what everyone was talking about. I didn’t want to miss a moment of anyone’s subplot— every character had one—but there was simply no way I could be in two places at once; I couldn’t hope to hear all of the gossiping of the closet lesbians and uncover the history between childhood companions (now strangers) Alexei and Tatiana, and I felt horrible leaving the room while the Austrian concert violinist performed a solo. I was amazed when the other passengers responded to me in the hallway or dining compartment according to my prior behavior and interactions.

The Last Express is one of the greatest adventure games ever made, but few have played it

Unfortunately, the timing of its release could not have been worse. Publisher Brøderbund’s entire marketing staff quit the company shortly before the game hit store shelves. Despite taking four years and a then-astronomical $5 million to develop, The Last Express appeared with no marketing. As you might expect, it failed to make a splash, despite great praise from the few people—including editors at Newsweek and USA Today—who did play the game. It went out of print in under a year, as Brøderbund’s troubles compounded. (Thankfully, the game is now available for play on modern systems.)

This was perhaps emblematic of the adventure genre’s downfall. Development costs were increasing, while sales (in North America, at least) dropped off and marketing for adventure games utterly failed to draw the attention of a mainstream audience. Similarly, The Last Express offered some of the most innovative, forward-thinking mechanics and ideas in video games, but these were mired in a sometimes-clunky interface and a handful of horribly-awkward unskippable action sequences. The genre needed to move forward, but it seemed determined to keep one foot firmly planted in the past—staunchly clinging to outdated conventions and infuriatingly unintuitive puzzles.

End of an era

Sierra was purchased by CUC International in 1996. Ken Williams relinquished executive control for the first time in the company’s history as Sierra’s heart and soul was systematically ripped apart by corporate greed. Lay-offs came hard and fast while creativity suffered, and the new management pushed for maximum productivity. CUC was later embroiled in a high-profile accounting scandal that caused company stocks to plummet and led to the imprisonment of high-ranking executives. Sierra was sold to Vivendi in 1998, with months of lay-offs and division closures immediately following.

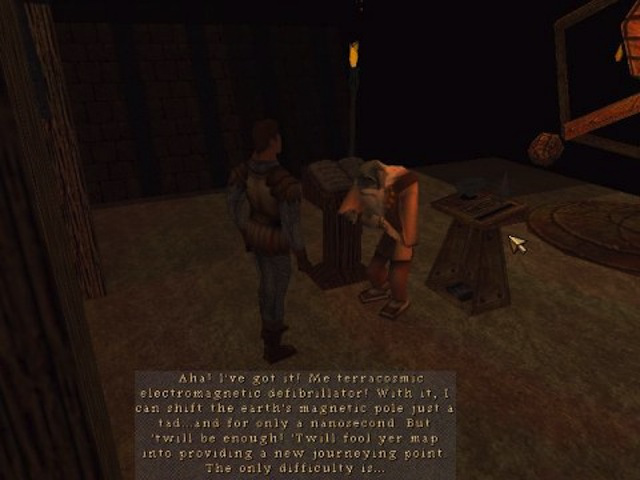

Amidst all this chaos, Sierra attempted to bring the long-running King’s Quest series into the modern era with a fully-3D engine. Released in December 1998, King’s Quest: Mask of Eternity tanked both commercially and critically. Gabriel Knight 3, released the following year, did little better—despite more positive reviews. Back-room drama had clearly taken its toll on the quality and charm of Sierra’s adventure games.

King’s Quest: Mask of Eternity tried to modernize the long-running series with a switch to polygonal 3D graphics. It failed

On February 22, 1999, the company’s original studios in Oakhurst were closed—leaving more than 250 people without a job. Sierra would continue to operate until its Bellevue offices were closed in 2004, but it had long since fallen into irrelevancy. The company that more or less defined the graphic-adventure genre was dead in all but name.

The meteoric rise of the first-person shooter certainly wasn’t helping the ailing adventure genre, which no longer sat at the pinnacle of gaming technology and could not hope to match the immediacy of its new rival in terms of immersion or reward-based mechanics. Many looked to third-person action adventure hybrids, such as Tomb Raider, Resident Evil, and Metal Gear Solid. Adventure games simply weren’t keeping up, as far as the gaming public was concerned. And even the game that is still held up as Tim Schafer’s magnum opus could not stem this changing tide.

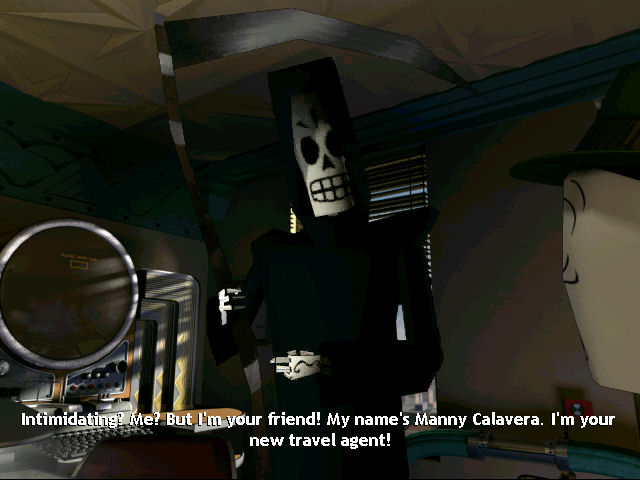

Grim Fandango eschewed the aging SCUMM engine in favor of a new 3D engine called GrimE, which rendered characters and objects in 3D on top of pre-rendered backgrounds. The game set its story in the style of film noir—which coincidentally also formed the core of the following year’s Discworld Noir—and in the world of Mexican folklore. Controlling Manuel “Manny” Calavera, a travel agent in the Land of the Dead, you set out on a journey to save a saintly client and uncover a ring of corruption. Grim Fandango was widely praised for its brilliant story, art style, and audio, but it sold fewer than 100,000 copies in North America.

What do you get when you cross Mexican folklore and film noir? A Tim Schafer masterpiece

LucasArts released one more graphic adventure, Escape from Monkey Island (2000), before canceling development on sequels to Sam & Max and Full Throttle. Tim Schafer left the company in January 2000 to found Double Fine Productions, which is perhaps best known for adventure hybrids Psychonauts and Brütal Legend. The two companies whose names were synonymous with the graphic-adventure genre had abandoned it under volatile market conditions and rising development costs.

Pundits, observers, and despairing fans called the adventure game dead. The genre had gone from dominating the computer games market to struggling for air. But it had a little life left in it.

A lifeline across the Atlantic

While the genre was hemorrhaging in the United States, across the Atlantic adventure games continued to thrive. In the first half of the decade, Adventure Soft’s Simon the Sorcerer games had put a British spin on the LucasArts comedic adventure formula—to great success. In 1997, the developers followed this with The Feeble Files, a science fiction comedy in the traditional point-and-click style that cast players as a “feeble” alien called Feeble, who inadvertently gets caught up in a plot to overthrow his Orwellian overlords.

The Feeble Files had a fantastic concept and great humor, although its overall design was less impressive

Funcom’s 2000 release of The Longest Journey proved the genre’s continuing relevance in video game storytelling, with some of the best writing yet seen in the medium. Lead character April Ryan displayed a rare strength and maturity for women in games, using her intelligence and wit—rather than good looks and sexuality—to overcome adversity, as she underwent a journey across parallel worlds that mirrored her own personal growth.

The Longest Journey tells a traditional coming-of-age story in a grand setting across two distinct yet interconnected worlds

The Longest Journey‘s structure fell rather more in line with traditional narrative than the typical adventure game. It had the kind of story beats you might expect from a coming-of-age fantasy tale. April’s realistic characterization juxtaposed perfectly with the ridiculousness of her calling to save the world, and the game only really suffered from the same problems that plagued nearly every other adventure—a clunky inventory system, a distinct lack of true player agency, and a number of nonsensical puzzles.

French developer Microïds furthered the cause for strong and smart female leads with the 2002 release of Syberia—a gorgeous-looking game that combined Art Nouveau and steampunk in both its story and setting. With inventive mechanical puzzles, well-written characters and dialogue, and a fine attention to detail, it was a stand-out release that deserved more attention than it received. But it did well enough to warrant a sequel, which arrived in 2004 and was generally well-received.

Microïds Syberia wowed critics and fans with its detailed graphics

Many American-developed adventures barely made a mark in the US but sold well in Europe around this time—including the real-time-3D point-and-click Blade Runner and DreamForge’s psychological thriller Sanitarium. The gulf existed well into the next decade, as Spanish developer Péndulo Studios released the sometimes-hilarious Runaway: A Road Adventure in 2001—a game which sold in huge quantities throughout Europe, but took two years even to get published in the United States.

The rise of episodic gaming

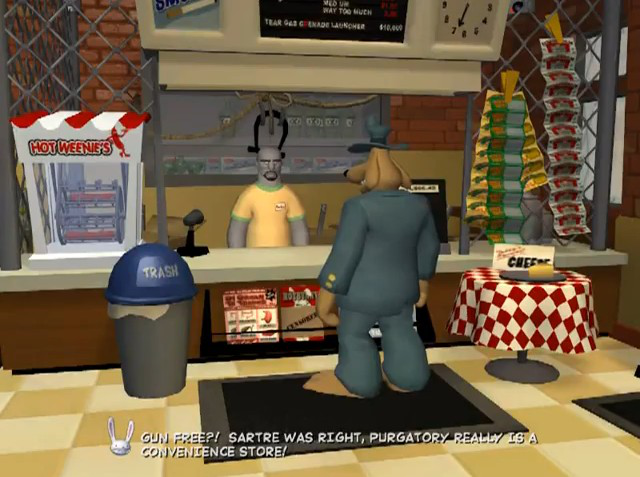

The European market continued to prop up the adventure genre until 2006, when Telltale Games began an episodic series of Sam & Max games—having acquired the rights in late-2005. Telltale did precisely what Ron Gilbert had done when creating SCUMM; it replaced the most inaccessible, unintuitive element of adventure games—in this case, the puzzles—with an equivalent that did not leave players pulling their hair out in frustration. The convoluted logic of 1990s and early-2000s adventure games was now a thing of the past.

Telltale’s Sam & Max also brought the dated interface and inventory systems into modern times, with context-sensitive options/actions and no more fruitless clicking to see whether two items could be combined—if an item is relevant to the puzzle at hand, you need only click on it once. This change came with no loss of humor or zaniness, and only a slight loss in charm—although that was mostly due to the transition to 3D graphics.

Telltale’s episodic Sam & Max games have now spawned three seasons, each more finely tuned than the last

Gamers and critics embraced the new games, and the genre seemed poised for a comeback—with the most popular and beloved adventures of the ’90s receiving remakes or ports for the Nintendo DS, PC, home consoles, and megahit iPhone. Console-oriented adventures Indigo Prophecy and Heavy Rain met a strong audience, while Nintendo Wii adventure Zack & Wiki: Quest for Barbaros’ Treasure was critically acclaimed. Smaller studios had greater success with the proliferation of digital distribution, and Telltale went from strength to strength—creating episodic adventure game spin-offs of Wallace and Gromit and Strong Bad, in addition to reviving the Monkey Island series under guidance from Dave Grossman.

Zack & Wiki proved the Nintendo Wii could be a great platform for graphic adventures, but it sold poorly

Now on the horizon are new games from Telltale and Whispered World-creator Daedalic Entertainment, as well as a third Syberia game, a new title from Gabriel Knight writer/designer Jane Jensen, and a remastered edition of Broken Sword II. Whether the genre can return to its former glory remains to be seen, but it’s a good time to be a graphic adventure fan.

Epilogue

In its sometimes-turbulent thirty-year history, the graphic-adventure genre has driven technology adoption, ridden at both the crest and trough of the graphics and audio waves, touched the lives of millions of people, and shaped the rise (and, in some cases, fall) of several big-name people and companies in the gaming industry. It’s a genre that has often been held back by its own insularity, suffering from an unwillingness to adapt to changing market conditions or to further push the boundaries of interactivity. Adventure games certainly did these things, but the efforts to truly innovate seemed to peak in the mid-’90s, before rapidly falling off—with only a few exceptions. The improving fortunes of adventure game developers in recent years may at least in part be attributable to their efforts to innovate—Telltale with the episodic structure, Quantic Dream with a new control system (for better or worse), and Japanese developers such as Cing with Nintendo DS titles that introduce elements from visual novels.

The rise of casual games hasn’t helped the ailing genre, though, with hidden-object games (of which there are very many) often being marketed as kinds of graphic adventures—thus making it harder for deeper, more serious offerings to wade through the crowd and draw public attention.

Even if adventure games never do return to the pinnacle of computer gaming, their pioneers can rest assured that theirs was a genre that has long been a bastion for serious storytelling in video games and undeniably influenced all development in the medium. Beyond pure technological innovation, adventure games drove improvements in interface design, sound design, writing, dialogue, and art direction. Some mechanics and concepts, such as the rewind-time mechanic most famously used in Braid and Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time or the embedded movies found in all kinds of games, debuted in adventure games. And they remain the best demonstration of how comedy and humor can work in video game form.