Ever since the iPhone came out in 2007 and almost instantaneously overshadowed the Mac, both in terms of sales and development resources, Apple has been making the Mac a bit more like the iPhone. Sure, a few features have moved the other way—the iPad has gradually gotten a bit more Mac-like as it has become powerful enough to do Mac-like things—but a big piece of every macOS release this decade has been “here’s all the stuff Apple brought over from iOS this year.”

Catalina moves macOS further and more decisively in the direction of iOS than ever; for the first time, third-party code written for iOS and iPadOS can run on the Mac with relatively few changes. At the same time, Apple remains adamant that the Mac and iOS/iPadOS are separate platforms that differ in ways that go beyond the underlying processor architecture or the primary input mechanism.

Catalina also draws clearer lines between the two platforms than we’ve gotten before. Apple has both said and done things that only make sense if the Mac will still be able to run whatever code you want for the foreseeable future, even as the default settings and security mechanisms become more locked-down and iOS-y. The overwhelming success of the iPhone indicates that most people are fine with Apple’s restrictions most of the time. But the slew of new desktop hardware we’ve gotten in the last couple of years suggests that Apple understands that a valuable, vocal chunk of the Mac user base (and the developers who drive the iPhone’s and iPad’s success) still wants powerful hardware that runs more flexible software.

Despite continued angst about what it means for apps to be “Mac-like,” the Mac will continue to be the Mac, distinct from the iPhone and the iPad. Keep that in mind as we dig into Catalina, which changes a whole lot of stuff about how Macs work while still aiming to preserve what people like about them.

Table of Contents

System requirements and compatibility

After dropping a pretty long list of older Macs in Mojave last year, Catalina leaves compatibility alone with one minor exception. Just about anything that will run Mojave will run Catalina:

- MacBook (Early 2015 or newer)

- MacBook Air (Mid 2012 or newer)

- MacBook Pro (Mid 2012 or newer)

- Mac mini (Late 2012 or newer)

- iMac (Late 2012 or newer)

- iMac Pro (2017)

- Mac Pro (Late 2013)

For the most part, support for Catalina continues to be tied to support for the Metal graphics and compute API, and making it easier for developers to port their iOS apps to the Mac is probably the justification.

But we’ve reached the end of the line for the old, pre-trash-can Mac Pro, regardless of how much you’ve upgraded yours in the last decade. While Mojave would run on old 2010 and 2012 Mac Pros with upgraded Metal-compatible graphics cards, Catalina will not. And while you may be able to trick Catalina into booting on these systems with minor modifications, Apple has apparently stripped out older drivers needed to make some Wi-Fi adapters and graphics cards work properly in those Mac Pros.

Apple maintains, as it has for the last few macOS releases, that the system requirements for any given version of macOS loosely lines up with its hardware policies for “vintage” and “obsolete” products. Anything discontinued more than seven years ago, as these old Mac Pros were, is considered obsolete, and the company will guarantee neither hardware nor software support for those Macs. Regarding the Mac Pros in particular, there’s also been some speculation that Apple doesn’t want to continue to support them because Intel isn’t releasing microcode updates for those processors to mitigate some of the hardware-level security flaws that have been disclosed in the last year or two.

The removal of support is unfortunate, given that there’s no reason why that Mac Pro hardware couldn’t run Catalina if its GPU were up to snuff; Apple is also dropping those old Mac Pros just in time to sell you a brand-new, tower-style Mac Pro for several thousand dollars. This feels too convenient to be a total coincidence, but it’s unlikely to affect many people at this point.

Even among the Macs that can run Catalina, a small handful of features are only officially supported on newer devices. The new Sidecar feature, which lets you use an iPad as an external monitor via a wired or wireless connection, requires a Mac with hardware acceleration for HEVC video encoding. That means you need a sixth-generation (Skylake) or newer Intel processor in your Mac (and/or an Apple T2, which can handle HEVC encoding).

- MacBook (Early 2016 or newer)

- MacBook Air (2018 or newer)

- MacBook Pro (2016 or newer)

- Mac Mini (2018 or newer)

- 27-inch iMac (Late 2015 or newer)

- 21.5-inch iMac (2017 or newer)

- iMac Pro (2017)

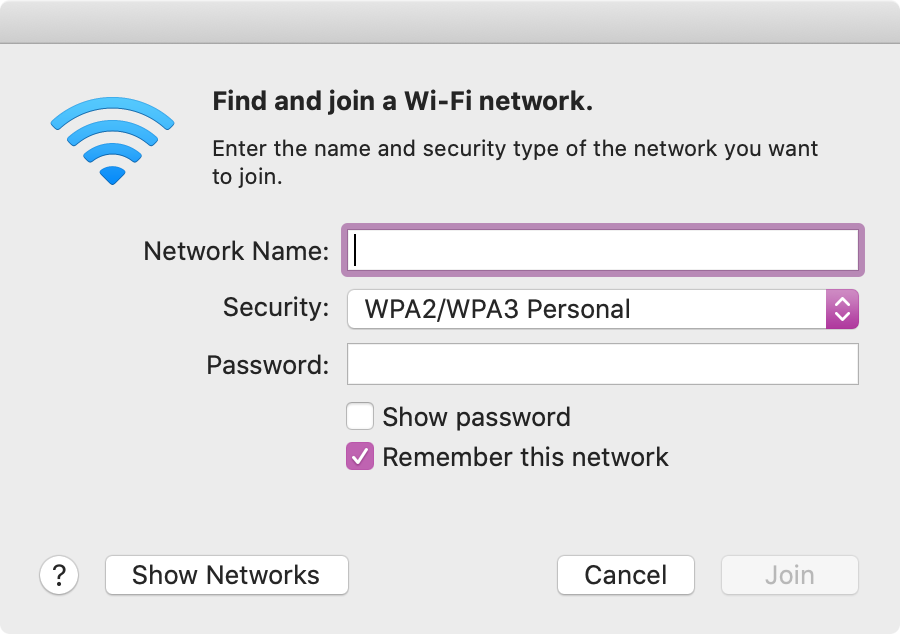

Apple Watch unlocking and WPA3 Wi-Fi encryption support requires a Mac with 802.11ac support. That covers any Mac released in 2013 or later; the 2012 Macs on the Catalina support list are the only ones that still use 802.11n adapters.

What should I do with my unsupported Mac?

If you’ve got an older Mac that you’re still happy with, you have some options. The easiest is to continue running either High Sierra or Mojave, depending on what version your Mac supports. Apple typically supports the previous two versions of macOS with security updates and new Safari versions, so High Sierra should be supported for another year, and Mojave should have two years of patches left. Apple may make some changes to iCloud or other services that break certain functionality (changes to the Notes and Photos apps have, in the past, been unable to sync correctly with older versions of macOS and iOS). But the operating system itself and most third-party apps will continue to work fine—and you’ll still be reasonably secure.

Another, less-satisfying option is to install another operating system. Nothing should keep Windows 10 or most Linux distributions from running on these Macs, though you may have trouble finding modern drivers for the oldest systems. The home version of Neverware’s CloudReady operating system can turn most older Macs into ersatz Chromebooks, which is a decent fit for computers with older processors and 2GB or 4GB of RAM. All of these will take you out of Apple’s software ecosystem (aside from the limited browser-based iCloud apps and iCloud for Windows), but they’ll keep your old computers (relatively) secure and functional.

When Mojave dropped support for a bunch of Macs last year, it prompted some enthusiasts to develop workarounds that would make the operating system (mostly) work on older unsupported systems. DosDude1’s Mojave Patcher Tool is probably the easiest and most extensively documented, and he has been working on a Catalina patcher that seems to support most of the same systems with most of the same caveats. I wouldn’t recommend this for most people; at best these Macs suffer from minor graphics, camera, and trackpad issues, and some older AMD Radeon GPUs will essentially refuse to run the software at all. I can’t speak to which features these Macs are missing, or whether they’ll be able to run Catalyst apps at all. But if you’ve got an older Mac you just can’t give up, this is something you can try.

Branding, installation, and free space

The state of California has 842 miles of coastline, more than 3,000 lakes, dozens of small islands, multiple distinct biomes, and at least one noteworthy estuary. It’s the nation’s third-largest state by land area, its first-largest by population, and if it were its own country it would be the world’s fifth-largest economy. If you were to decide, say, to name your operating system releases after California locations, you’d have an unbelievably large and diverse group of locations to choose from.

So why are the people who name macOS releases so obsessed with rocks?

Save for Mavericks, which used beach-y wave iconography, all of the other California-themed macOS releases have been all about rocks. Yosemite is a park known for its hiking and rock climbing, and El Capitan is a reference to a specific rock within that park. Both Sierra and High Sierra are named for the same mountain range (mountains are big rocks). The desert-themed Mojave almost breaks the cycle, but deserts are full of sand, and sand is mostly little tiny rocks. The desktop wallpaper was a mountain of sand, small rocks piled together in imitation of a big rock; in some ways, it is the rockiest of all. And then we come to Catalina.

Downloadable macOS installers through the ages. Credit: Andrew Cunningham

Santa Catalina is a small, sparsely populated island off of California’s southwestern coast. It’s only 22 miles long from end to end, and the branding Apple uses appears to be a head-on photo of its western tip. It is, at least, a rock with water around it. But, nevertheless, rocks.

Does this rock fixation have something to do with macOS’ status as the bedrock of Apple’s ecosystem, the small-but-vital chunk of its business from which iPhone and iPad apps spring? Is it a reference to the operating system’s rock-solid Unix foundation? It’s hard to say. But I challenge the Mac team to come up with a name for next year’s release that references a forest or a field or something else green and growing.

The install process for Catalina is mostly the same as for Mojave; download the installer from the Mac App Store and then run it to upgrade. It’s still possible to create a USB installer for Catalina if you’ve got a slow Internet connection and a lot of Macs to upgrade, but that feature is slowly becoming less convenient than it used to be since Macs with the Apple T2 chip can’t boot from external media by default and any Mac with a T1 or T2 typically needs to connect to the Internet during setup anyway so it can download and install updates for the BridgeOS software that makes them work.

A fresh, fully indexed installation of Mojave 10.14.6 takes up 15.1GB of space on a 2018 Mac Mini (counting the main OS volume and the recovery volume but not the volume used for virtual memory), and its installer is 6.05GB in size. The GM build of Catalina has an 8.09GB installer—a fairly large increase—but takes up the same 15.1GB of space (again, not including the VM partition). The read-only system partition accounts for about 10.6GB of that, while the data partition is only 3.8GB to start.

The end of 32-bit apps (and other removals)

Mac hardware and macOS made the jump from 32 bits to 64 bits a long time ago, but Catalina will be the very first version of macOS that is totally unable to run 32-bit software. For (what I hope will be) the last time, let’s review the Mac’s entire 64-bit timeline from start to finish:

- June 2003: The PowerPC G5 CPU is the first 64-bit-capable chip to show up in a Mac, and with Mac OS X 10.3 Panther, it can theoretically address up to 8GB of RAM.

- April 2005: Mac OS X 10.4 Tiger allows for 64-bit processes under the hood—they can be spun off from another process or run via the Terminal.

- June 2005: Apple announces that it will begin using Intel processors, which are still primarily 32-bit. Whoops!

- August 2006: Apple launches the Intel Mac Pro with a 64-bit Woodcrest CPU; mainstream 64-bit Core 2 Duo Macs follow shortly afterward.

- October 2007: Mac OS X 10.5 Leopard launches with actual support for regular 64-bit apps; Universal Binaries can run on 32-bit and 64-bit Intel and PowerPC machines, covering four architectures within a single app. Unlike Windows, Apple never ships separate 32- and 64-bit versions of Mac OS X.

- August 2009: Mac OS X 10.6 Snow Leopard still runs on 32-bit chips, but for the first time everything from the apps to the OS kernel supports 64-bit operation. Snow Leopard’s 64-bit capabilities are a major component of Apple’s marketing push, which infamously includes “no new features.” However, most systems still default to loading the 32-bit kernel.

- July 2011: Mac OS X 10.7 Lion drops support for 32-bit Intel CPUs (Snow Leopard had already ended all support for PowerPC systems). Older Macs continue to default to the 32-bit kernel and 32-bit drivers, but new Macs introduced in this era typically default to the 64-bit kernel.

- July 2012: OS X 10.8 Mountain Lion boots into the 64-bit kernel by default on all systems that support it, including a few that previously defaulted to the 32-bit kernel. In the process, a few 64-bit systems with 32-bit graphics drivers and 32-bit EFIs are dropped from the support list.

- June 2017: Apple announces macOS 10.13 High Sierra and says it’s the last release that will run 32-bit apps “without compromise.”

- January 2018: All new apps submitted to the Mac App Store need to be 64-bit only.

- April 2018: High Sierra’s 10.13.4 update begins warning users about “not optimized” (read: 32-bit) apps the first time they’re launched.

- June 2018: All new apps and updates to existing apps submitted to the Mac App Store need to be 64-bit only. Apple announces macOS Mojave, which will be the last version of the OS to run 32-bit code.

- September 2018: Apple releases Mojave. 32-bit software continues to run but with more frequent and aggressive nag messages than High Sierra.

- June 2019: Apple announces macOS Catalina, which makes good on Apple’s promise to drop 32-bit software support.

- October 2019: Catalina is released. 32-bit apps no longer run on the latest version of macOS.

Assuming nothing changes about Apple’s typical macOS update practices, Mojave will stop getting security updated when macOS 10.17 is released in the fall of 2021. At that point, no currently supported version of macOS will be able to run 32-bit software. And a few longstanding components of macOS haven’t made the jump to 64-bit. These include anything related to the legacy QuickTime Player 7 app, the InkServer handwriting-recognition service (now replaced, more or less, by Sidecar and its Apple Pencil support), the old Apple-maintained Java 6 Runtime, and the long-deprecated Carbon API and any apps built using it.

32-bit apps will refuse to run on Catalina. Credit: Andrew Cunningham

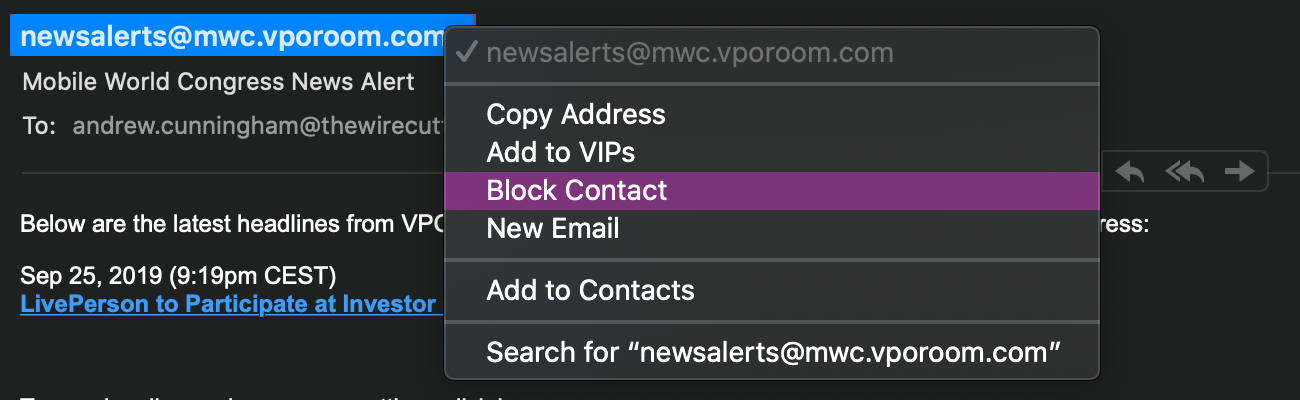

Apple was careful not to surprise anyone with Catalina’s removal of 32-bit support, and the company has been projecting its plans for over two years now. Most developers took the hint, and even software like Audacity and Zoom that was still 32-bit as I wrote the Mojave review last year is 64-bit now—though larger, more complicated apps might still be hung up on old 32-bit dependencies that need to be either updated or replaced. 32-bit apps will remain installed on your Mac, but their icons will be crossed out. Trying to run those apps will only result in a prompt that your software is out of date as well as a link to the Apple support page about 32-bit software.

If you want to check to see which of your Mac’s apps are still 32-bit, open the System Information app and scroll down to Legacy Software. Affected apps and components of otherwise 64-bit apps will appear organized by developer, or under a separate heading if they’re from the Mac App Store. The Catalina installer will also warn you about 32-bit apps before you start the upgrade.

The impact of the 32-bit decision will be felt disproportionately. Regular users are unlikely to notice or care—or, at least, it will be reasonably easy to find replacement or updated versions of older apps that support 64-bit. Creative professionals, on the other hand—people who work with images, video, or audio, or folks who rely on expensive (and not always new) external equipment may run into problems with apps, or plugins, or drivers. Community-maintained open-source software is likely to lag behind software maintained by large companies. If you’re holding on to older versions of these pro software packages before the whole professional software industry shifted to yearly subscriptions with rolling updates, those apps may not have 64-bit compatibility and certainly won’t have it added in an update. And while I don’t think macOS is the gaming platform of choice for many people, tons of older games (and, as of this writing, the regular Steam client) are 32-bit only and are extremely unlikely to be updated.

OpenGL and OpenCL

OpenGL and OpenCL were officially deprecated in Mojave last year, though that’s a little misleading since it implies that Apple had been actively maintaining and updating its support for those standards. In Catalina, as in every macOS version going all the way back to Mavericks, the macOS OpenGL implementation is stuck at version 4.1 (2010), and the OpenCL version is stuck at 1.2 (2011). This means that apps that still rely on those APIs on macOS will continue to run, provided they’ve been updated to meet the 64-bit-only requirement. But you shouldn’t be developing new Mac apps that rely on OpenGL or CL for anything important.

Apple also isn’t directly supporting newer replacement standards like Vulkan. Instead, the company is opting to direct developers toward its own proprietary Metal API for both graphics and GPU computing. But that doesn’t mean there’s no hope for cross-platform developers—the MoltenVK translation layer, which maps Vulkan API calls to Metal ones, is actively being used in several prominent apps, and the results are promising. In both Dota 2 and the Dolphin GameCube and Wii emulator, MoltenVK often performs significantly better than OpenGL while saving developers the trouble of adding and maintaining Metal support. It’s not totally without bugs (and as those Dota 2 benchmarks from Phoronix show, still not quite as fast as Vulkan running on Linux or Windows 10), but MoltenVK is still a big improvement over OpenGL.

Dashboard is dead

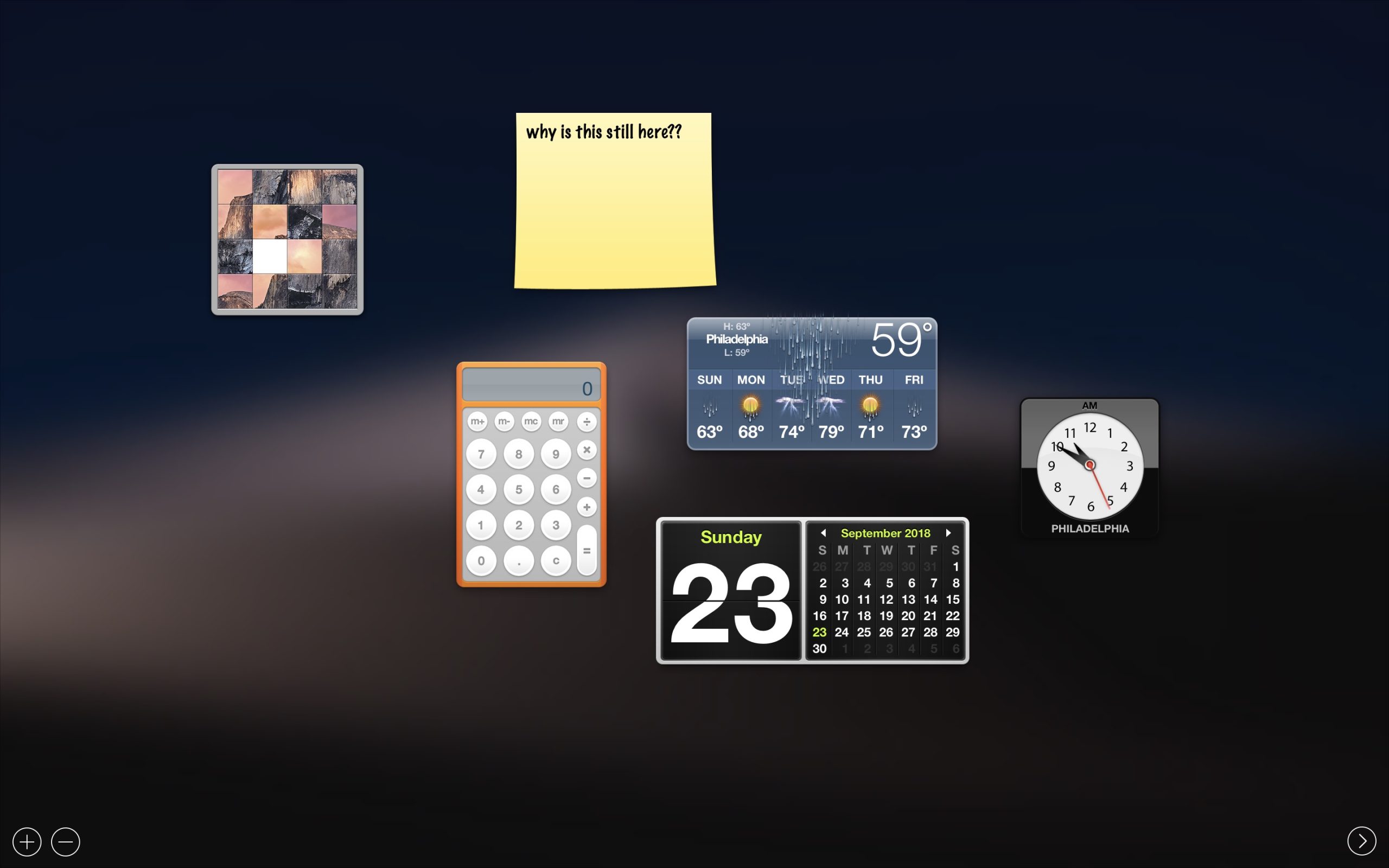

The Dashboard in Mojave. Goodnight, sweet prince. Credit: Andrew Cunningham

Catalina finally kills the Dashboard, a feature introduced 14 years ago in version 10.4 and updated infrequently and sporadically since then—it was the only place in Mojave where the old Scott Forstall-era software design language was still readily visible. Dashboard has been disabled by default since macOS Yosemite in 2014, but it has soldiered on, partially broken and unnoticed, until now.

The bulk of Dashboard’s widgets (including the weather, calendar, world clock, and calculator) could already be replicated in the Today view in the Notification Center. If you had sticky notes stored in Dashboard, upgrading to Mojave moves them to the Stickies app. I suspect a small faction of Dashboard die-hards will lament the demise of a treasured workflow or declare these substitutes to be Not Good Enough, but the rest of us won’t notice.

Python, Perl, and Ruby

For years now, Apple has shipped runtimes for the Python, Perl, and Ruby programming languages to allow users to run scripts written in those languages without performing any additional installs. But according to Apple’s release notes for developers, “future versions” of the operating system will stop including those runtimes by default (though they may still be able to download the runtimes on-demand, just as older versions of macOS could download the Rosetta PowerPC compatibility layer or Java when needed). Apple recommends that developers whose software relies on one or more of these runtimes ship their own runtimes alongside their apps.

Anyone who relies on the built-in versions Python, Perl, or Ruby can breeze through installation using Homebrew or other methods, and the versions that Apple ships usually sometimes trail the current stable releases by several versions. If you do choose to use the built-in versions, Catalina does include Python 3 by default, where older versions of the operating system only included Python 2.7 (still included, and still the default environment if you just run “python” from the Terminal, but Apple warns against using it).

New features: Finder and window management tweaks

After radically overhauling the Mac user interface with Dark Mode in Mojave last year, Catalina does almost nothing to shake things up. There is a new “auto” setting that will let your Mac use Light Mode during the day and switch automatically to Dark Mode at night, but otherwise things look and feel the same. The biggest change is to window management, and even that is mostly just an extension of features that were already available.

Hovering over the green stoplight button in any app now displays a pop-up menu with a few window management options. Apps that support Full Screen mode can be tiled to the left or right of the screen, which will gather all your other Full Screen windows on the other side so you can select a second app to use in Split View mode. Apps that don’t support Full Screen (or apps that do, if you press the Option key as you hover) can be sent to the left or right half of the screen without entering Full Screen mode. If you have a multi-monitor setup (or if you have a Sidecar-compatible iPad within range, whether you’re actively using it or not), this menu will bounce windows over to a different screen if you’d like. All of these window management options are also accessible from the Window menu in any app (though none of them have shortcut keys assigned by default).

The Full Screen app tiling was already present in Mojave if you clicked and dragged the green stoplight button in any Full Screen-compatible app—I am fully confident that almost nobody was aware of this functionality, but if you were, this behavior is no longer available in Catalina.

Other Finder changes are few and far between. Click the Markup button in a Quick Look window or anywhere else that supports Markup, and there’s a new button that will send images and documents over to your iPhone or iPad so you can mark it up with your fingers or an Apple Pencil (and changes are reflected in real time on the Mac’s screen). File metadata in the Finder’s column and gallery views has been rearranged to make it a little easier to read. And Apple has rebuilt the Open With menu in Finder (which carries over to Mail and Calendar, when opening attachments) so that it loads more quickly.

System Preferences, refreshed

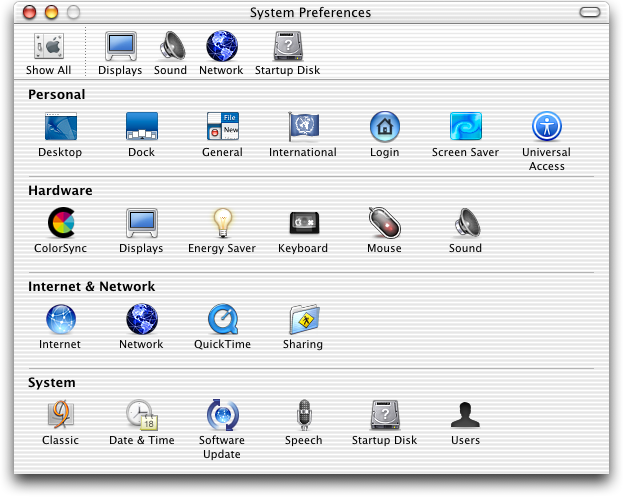

Every macOS release has included its own tweaks to the System Preferences app—icons have moved around or gotten updated, text labels have disappeared or been tweaked—but overall, things have looked more or less the same since Mac OS X version 10.1 (!) separated the icons into four loosely related rows.

Between Puma and Mojave, the text labels disappeared, icons changed, items were added and removed and shuffled around, and a search function made things easier to find, but the basic organization of the icons was the same.

System Preferences in Mojave. Credit: Andrew Cunningham

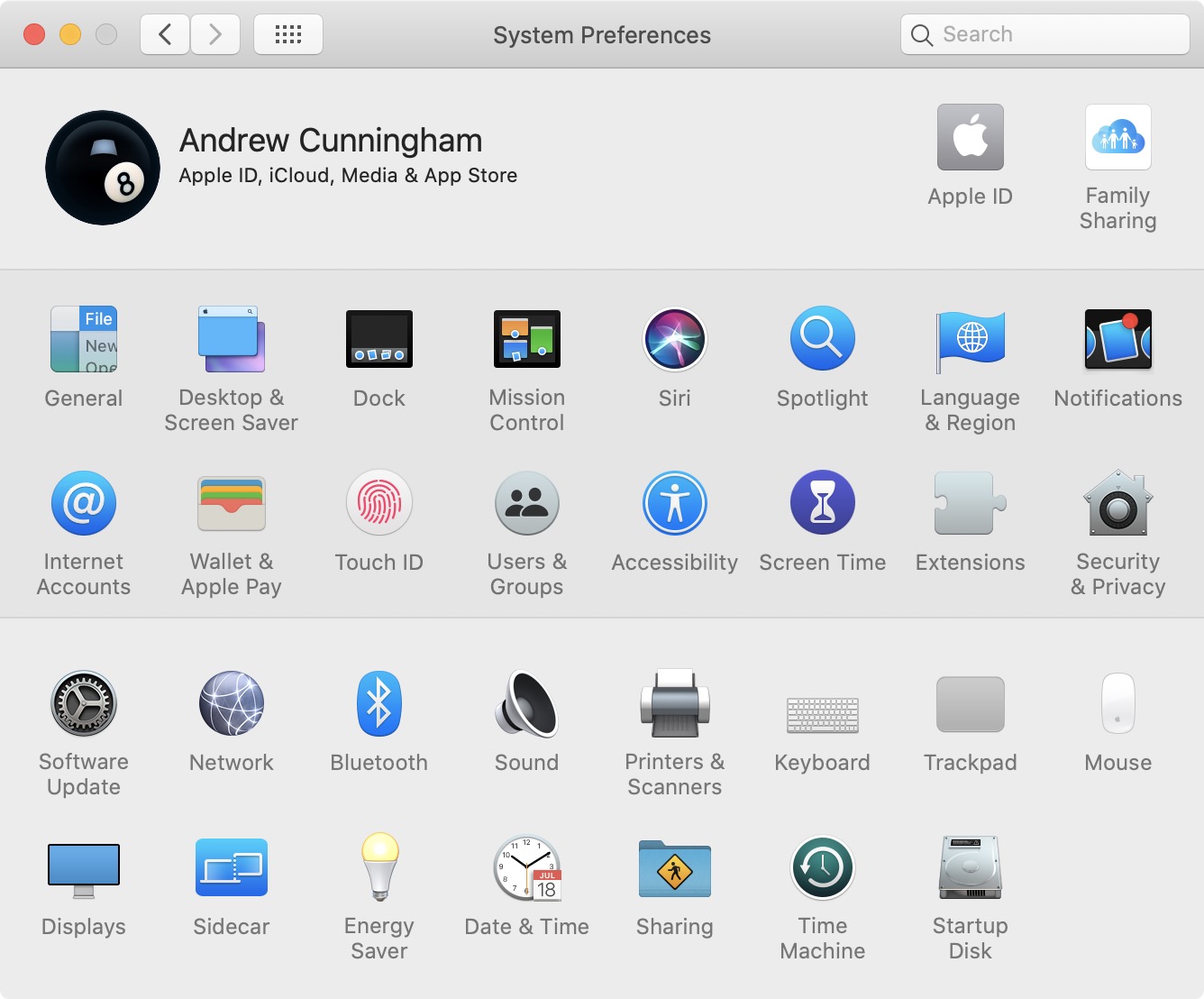

System Preferences in Catalina has been broken up into three different sections. Your Apple ID and Family Sharing settings have been placed right at the top, as is the case in the iOS Settings app, and both panes have gotten a total overhaul.

The rearranged System Preferences in Catalina. Credit: Andrew Cunningham

There’s not really anything in the new Apple ID pane that you couldn’t already see in the Mojave version of the iCloud pane, but it shows you all of your information with a fraction of the clicking—your iCloud settings and storage usage are still visible at the top level, and your list of signed-in devices is now immediately visible, too. Managing the rest of your account information is no longer in a separate tabbed menu but in several categories in the main preference pane. The new layout isn’t identical to the way that iCloud settings are presented in iOS, but it’s much closer than it was before.

The new iCloud settings. Andrew Cunningham

The Family Sharing preference pane is new, at least in the sense that it used to be a buried “Manage Family” button amongst the rest of the iCloud settings and is now a top-level menu item. From here, you can add, remove, and edit the details of individual family members’ accounts, as well as view and manage purchases and subscriptions, use location sharing, view shared Screen Time data, and set limits for your kids’ device usage.

Navigating most of the iCloud-related menus still feels slower than using the other preference panes, presumably because your Mac is actively reaching out to Apple’s servers to grab information in real-time rather than preloading anything. But the new layout should save clicks and make things easier to find, and it’ll be more familiar to people already accustomed to iOS or iPadOS.

Most of the other preference panes will look familiar; they’ve just been shuffled around. The middle section of System Preferences is populated primarily by preference panes that change settings related to the specific account that is currently logged in—though there are exceptions, like the system-wide user management in Users & Groups and FileVault and firewall settings in Security & Privacy. And the bottom section is mostly dedicated to hardware settings for networking, displays, printers, and audio devices as well as some system-wide settings for sharing, software updates, and Time Machine backups. These aren’t hard-and-fast distinctions—even with four separate icon groups instead of three, there was plenty of overlap. But it’s generally how things are organized now.

A few icons have been tweaked; the monitor icon for the Displays preference pane looks more like a Pro Display XDR than an old Apple Thunderbolt Display, with a slimmer bezel and a more squared-off, presumably $1,000 monitor stand. The Users & Groups preference pane gets a circular icon so that it matches better with the other predominantly circular System Preferences icons. And the Notifications icon is now a bit less abstract, showing what looks like a dock icon with a red notification badge rather than a blank gray square.

You might notice that one preference pane is missing entirely from Catalina: the Parental Controls pane from older versions of macOS is totally gone, replaced by Screen Time (or, at least, if you search for Parental Controls from the System Preferences search bar, Screen Time is the only thing that gets highlighted). If you have accounts with Parental Controls enabled, the Catalina upgrade completely removes those settings, leaving you with standard non-administrator accounts rather than managed accounts. Before you upgrade any Mac where you depend on managed local accounts, check to make sure Screen Time can do what you need it to do first.

Screen Time

Screen Time on the Mac is almost an exact replica of the feature Apple added to iOS 12 last year, just with a tweaked Mac user interface. If you’ve used it there, you know more or less what to expect. And if you were previously using the Mac’s Parental Controls to manage your kids’ computer usage, you’ll need to get used to Screen Time, since the old Parental Controls have been removed in favor of Screen Time’s app and usage limiting tools.

Screen Time functions both as a reporting tool and a limiting tool; by default when it’s on, all it does is passively track how much you’re using your devices, what apps you’re running, and how many notifications you’re getting. Like the iOS version, the macOS version can display usage information from other devices signed in to the same iCloud account, though this is disabled by default. But if you’re trying to impose limits on your own application usage or trying to limit someone else’s, Screen Time provides time limits for individual apps and categories of apps as well as controls for limiting purchases from Apple’s media stores and the kinds of websites that can be accessed.

The Mac’s app usage timing feels less flexible and less useful because the operating system doesn’t seem to be able to tell the difference between an app that is running and has focus and one that is simply open, somewhere. I’m not always using Messages or Mail or Slack when I’m using my Mac, but I do almost always have them open, so pretty consistently my browser and the apps I always have open (including the Finder) are all listed as running for the exact same amount of time. This is true even if the app’s windows are all minimized to the dock, or if the app is running but has no windows open. If you’re using Screen Time on the Mac to limit application usage, I can imagine someone who is used to the iOS rules (the app only counts against your time when you’re actively using it) being confused as to why they’ve run out of time on an app they used for two minutes and then forgot to quit or didn’t quit properly.

In addition to managing your own settings, Screen Time can be used to manage app limits and other settings for any kids in your iCloud Family Sharing family—those accounts all show up under a drop-down menu in the Screen Time preference pane. Since Screen Time is intended to replace the old Parental Controls, it would be nice if you could also manage other local accounts on your Mac, instead of needing to do everything through iCloud. You could always sign in to your kid’s local account and manage Screen Time settings from there, but I could see it being an issue for kids who want to have a sense of privacy and parents who trust them enough to give it to them (I have only been a parent for two months and thinking about all of this is already making my head spin). In any event, this is an edge case, and most people are likely to be fine with handling everything via iCloud anyway.

Voice Control

Voice Control’s status icon. Andrew Cunningham

Of all the accessibility features in macOS, Voice Control is the most transformative. It’s sort of an extension of the existing voice dictation features in the operating system, but it’s considerably more powerful—users can now control the entire operating system completely hands-free, using only their voices.

I’ll say upfront that my intent here isn’t to evaluate how good this feature is, as I do not have a disability and don’t have much context for how well accessibility features actually work on this or any other platform. I do aim to tell you how the feature works, and I can tell you how well it worked with my reasonably clear, not-strongly-accented English. If you do want to read a bit more about how the feature works as told by those who need it, Steven Aquino has an excellent piece at MacStories with a few different perspectives.

Setting up Voice Control is done in the Accessibility preference pane, under the “Motor” subheading. The first time you enable it, the operating system needs to do a small download before installing the feature. When it’s installed, a small overlay with a microphone icon appears in one corner of your primary display (it can be repositioned as you see fit) and floats above all of your windows; as you speak, what your Mac hears is displayed in small text above that overlay so you can see in real time whether your commands are being understood properly. The Sleep toggle will disable and enable the feature without turning it off.

Learning how to use Voice Control requires learning an extensive set of specific command words (click the Commands button to see them all), but you pick up the basics surprisingly quickly. Apple’s introduction video is actual a fairly typical (if idealized) example of how it can be used—to launch apps, dictate and correct text, and interact with apps. Mouse clicks can be simulated using either the “show numbers” command, which places a number next to every clickable element in an app and lets you specify a number to click on a thing, or the “show grid” command that lets you click anywhere on your screen. Sometimes, as when you right-click things or interact with the menu bar, Voice Control is smart enough to show numbers alongside each clickable element automatically so you can make a choice relatively quickly.

Just because full control of your computer via your voice is possible doesn’t mean the implementation is infallible. Even in a controlled demo with Apple, the mics built into your Mac are going to miss words or misunderstand them occasionally, and that will be especially true on older Macs without additional voice-canceling microphones. If you’ll be using Voice Control extensively, I’d probably recommend a high-quality headset to minimize errors. And I can’t account for how it works with a stronger accent, or in different languages, or if your speech is impaired (though Aquino writes that the feature worked fairly well even with a stutter). Adding new words via the Vocabulary menu in the Voice Control preferences can minimize errors for uncommon or easily misheard words that you use frequently.

Apps built using the Electron framework (like Slack, Spotify, and a bunch of others) are also problematic. While regular Mac apps don’t usually need to be updated for the “show numbers” command to work properly, as of this writing it’s not working in third-party browsers like Chrome or Firefox (Safari is fine). Because Electron is, at its heart, a wrapper for webpages rendered with the Chromium engine, the typical Electron app gives you almost nothing when you say “show numbers.” In Slack and Spotify, the only elements that were seen as clickable were the stoplight icons. Hopefully this is something that can be fixed as browsers and their engines are updated to take advantage of Catalina’s new features, but it’s not clear whether this will actually happen.

Voice Control is designed for those who are physically impaired—users that can’t or don’t want to use their hands for input via a keyboard and mouse or some version thereof—but who are fully sighted. So much of the way Voice Control works depends on you being able to see either small number icons or text badges or the status of a cursor and exactly where it is in a form field or a block of text. It’s the opposite of the VoiceOver screen reader, which helps with limited vision but assumes mostly unimpaired use of your arms and hands.

Apple indicated to me that Voice Control isn’t intended as an alternate input mechanism for non-disabled users (though I certainly found it useful in a pinch when I wanted to do something but one or both of my hands were full of baby). If you’re able to use a keyboard and mouse/trackpad or any facsimile thereof, they’ll still generally be faster and more accurate than using your voice. And Voice Control’s reliance on sight for most of its cues means that it’s not a great way to control your Mac from across a room, either.

Sidecar: Your iPad is a monitor now

Sidecar—the new feature that allows newer Macs to use iPads running iPadOS 13 as external displays—isn’t a new idea. Apps like Duet Display have made this sort of thing possible for years, and those apps don’t come with the hardware restrictions that Apple has placed on Sidecar. It’s a classic case of Sherlocking; Apple’s version might not do all the same things, but it does enough that most people aren’t going to need to pay for Duet Display anymore.

Sidecar doesn’t have to be new or innovative to be a good idea, and it’s convenient to have this feature built right into the operating system. And while you can use Sidecar as just a plain-old external display (albeit with restrictions, which we’ll cover in a minute), it can also be used to add touch controls, Touch Bar support, and Apple Pencil input to a Mac.

Compatibility

On the Mac end of the connection, Sidecar requires hardware support for HEVC/H.265 video encoding, since Sidecar operates not by sending a typical display signal to your iPad, but by sending a video stream over either Wi-Fi or a connected Lightning or USB-C cable. If you look at Activity Monitor, the process that seems to be handling the heavy lifting when Sidecar is active is actually “avconferenced,” the same process used for video streaming when you’re using FaceTime.

In Macs with an Apple T2 chip, HEVC encoding and decoding is one of the many things that chip can handle. In Macs without a T2, it’s handled by Intel’s Quick Sync video encoding engine, even on Macs with dedicated GPUs that can do their own HEVC encoding. Intel added HEVC support in the Skylake processor generation, which means Sidecar support is effectively limited to Macs built after late 2015 and 2016:

- MacBook (Early 2016 or newer)

- MacBook Air (2018 or newer)

- MacBook Pro (2016 or newer)

- Mac Mini (2018 or newer)

- 27-inch iMac (Late 2015 or newer)

- 21.5-inch iMac (2017 or newer)

- iMac Pro (2017)

Going with H.264 instead would have maximized compatibility, but since HEVC videos are about half as large as H.264 videos of similar quality, HEVC does make more sense if you’re trying to deliver low-latency video over a wireless connection.

On the iPad end, Apple tells me that Apple Pencil support is the limiting factor, not HEVC encoding or decoding. That means the 5th-generation iPad, which does support HEVC via the Apple A9 chip but doesn’t support the Apple Pencil, isn’t compatible with Sidecar. The iPad Air 2 and Mini 4 are excluded, too (early Catalina and iPadOS 13 betas did allow Sidecar on those tablets, but support was removed fairly early on).

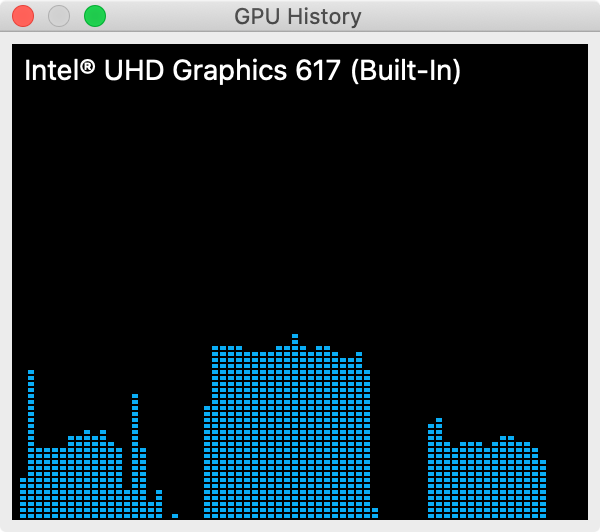

A Sidecar display does appear to be a bit harder on your Mac’s GPU than a typical monitor, probably because it has to handle HEVC encoding on top of rendering the stuff on the screen. Below is a shot of the macOS GPU History monitor; the tall usage peak in the middle is when I quickly swiped between two full-screen apps on my iPad Air 3 connected via Lightning cable, and the smaller peaks on the left and right are when I performed an identical task on the internal display of a 2018 MacBook Air (the Air’s display is set to a higher resolution, too—2880×1800, compared to 2224×1668). Trying to do this without hardware HEVC acceleration would probably be a bad time.

Because it’s also encoding an HEVC video stream, GPU activity on a Sidecar monitor is higher than on a regular monitor performing the same task, even if the regular monitor is set to a higher resolution.

Credit: Andrew Cunningham

Because it’s also encoding an HEVC video stream, GPU activity on a Sidecar monitor is higher than on a regular monitor performing the same task, even if the regular monitor is set to a higher resolution. Credit: Andrew Cunningham

Some Catalina beta users have had some success enabling Sidecar on unsupported Macs with Terminal commands, though it may not be possible in the final builds and doesn’t seem to work on all Macs in the first place (on my “old Mac” test system, a 2012 MacBook Air, the commands enabled the Sidecar preference pane after a restart, but I still couldn’t connect to anything). People with older Macs (or unsupported iPads) can continue using third-party software like Duet Display to enable similar functionality.

Using Sidecar

I tested Sidecar primarily on a 3rd-generation iPad Air and a 6th-generation iPad and a 2016 MacBook Pro, 2018 MacBook Air, and 2017 iMac. In all cases, I spent at least a little time testing the feature both wired and wirelessly.

Like Handoff and the Universal Clipboard and so many other features where an iDevice and a Mac talk to each other, Sidecar requires both of your devices to be signed in to the same Apple ID, even if you’ve connected your iPad to your Mac with a cable. This means multiple family members or coworkers can’t use a shared iPad for Sidecar unless their devices are using the same Apple ID. And because it uses the peer-to-peer Apple Wireless Direct Link (AWDL) to communicate rather than whatever Wi-Fi network you’re connected to, it requires your devices to have a reasonably good wireless connection. If the connection gets too weak, the iPad will show you an error message until you move back within range.

The Sidecar connection must be initiated from your Mac, either through the Sidecar preference pane in System Preferences, the AirPlay icon in the menu bar, or by sending an app window over to your iPad via the Window menu or by hovering over the green stoplight button—you can’t use it to connect to a Mac in another room or as a display for an otherwise headless Mac Mini. By default, your iPad will display a sidebar full of shortcuts and a Touch Bar strip across the left and bottom edges of the screen (respectively), but either or both bars can be repositioned or hidden from the preference pane if you’d prefer to maximize your screen space. The sidebar includes buttons for hiding and showing the menu bar and the dock, persistent keys for the Mac-specific control, option, and command keys as well as the Shift key and an undo button, a button that pulls up an iPhone-style software keyboard that can be moved anywhere you want it on the screen, and a button to disconnect from the Mac.

Move outside of the 20 or 30-foot range of Sidecar, and your connection may drop off until you move back into range. Credit: Andrew Cunningham

The Touch Bar works as it does on a Mac with a built-in Touch Bar, dynamically changing as you switch between tasks, though it only works for apps that are actually displayed on your iPad’s screen (and it doesn’t display the persistent system controls, like brightness and volume and media playback buttons, that you get on a built-in Touch Bar). The feature tends to assume that you’re working on a Mac with a built-in Touch Bar, even if you aren’t; The Touch Bar on your iPad’s screen won’t do anything if you’re working in a window on your Mac’s regular display; and trying to customize your pseudo-Touch Bar’s layout from within the Keyboards preference pane just doesn’t work. Even when you’re using your iPad as your main window, the customization controls show up on your Mac’s screen, and the normal behavior (where you click and drag buttons to the Touch Bar as though it was another, separate display) doesn’t do anything.

The sidebar and pseudo Touch Bar can be situationally useful if you’re actively holding the iPad as you use your Mac, like when you’re drawing with an Apple Pencil. But if you just want to use it as a regular external monitor, I always preferred to hide them and reclaim the extra screen space for apps.

Once you’re connected, your Mac treats the iPad pretty much the same way it treats any external display (though your Mac does know the difference between a Sidecar display and a real one; it shows up in System Information as a “virtual device”). It shows up in the Displays preference pane, and you can either choose to extend or mirror the displays, set either display as your main monitor, or tweak how your screens are arranged so that dragging windows and moving your mouse cursor between monitors works properly. There are a few limitations, though:

- Touch input doesn’t work as it does on iOS. You can’t, for example, click on things with your fingers, and you need to use two fingers if you want to scroll (though the new iPadOS gestures for things like copy, paste, undo, and redo all work). Outside of drawing apps, tapping the Apple Pencil works the same way as clicking and dragging with a mouse or touchpad; you can’t double-tap items to open them, but you can drag-and-drop files and images, or drag to highlight chunks of text.

- You can’t change your display’s scaling. Whether you want larger text or more desktop space, by default you’re stuck at normal 2x Retina scaling (so a 6th-gen iPad with a 2048×1536 display will always look like a sharper version of a 1024×768 display).

- Using Sidecar wirelessly, while it generally performs well enough for basic multitasking, can be a bit frame-y. It takes a lot longer to apply settings changes like hiding and showing the sidebar and Touch Bar.

- You can’t adjust color profiles.

- Your Mac’s sound can only come out of whatever speakers or headphones your Mac is connected to. You can’t use the iPad’s speakers or headphone jack to output Mac audio or the iPad’s microphone to record audio on your Mac.

Presumably because of the performance overhead of encoding multiple HEVC video streams at the same time, Sidecar can only work with a single iPad at a time. But that iPad doesn’t count toward the number of displays that your Mac’s GPU can drive at once (Intel’s GPUs are limited to three; AMD’s can drive up to six; Nvidia’s can handle four). A modern MacBook Air or Pro with an Intel GPU can drive its own external display, two external monitors, and a fourth Sidecar monitor at the same time.

Sidecar and iPad accessories

The Apple Pencil can be used as a pointing device in Sidecar, but drawing support may be its most appealing feature for artists who are already using Macs alongside drawing tablets from Wacom and other manufacturers. Any application that already supports drawing tablets should support Apple Pencil input via Sidecar. I primarily used Microsoft OneNote for testing, and Apple has shown Adobe apps like Photoshop and Illustrator in demos.

In OneNote, Apple Pencil tracking seemed pretty accurate, and the app respected the stylus’ pressure sensitivity just as iOS apps do. While the Pencil is definitely usable over a wireless connection in a pinch (or for quickly jotting something down), this is one case where you’ll definitely want to connect your iPad to your Mac with a cable for the best experience. When connected with a Lightning cable, I found that the tablet’s screen felt noticeably more responsive and a bit closer to the experience of drawing in a native iOS app.

If you use a keyboard with your iPad, whether it’s connected via Bluetooth or a Smart Connector, it functions as a normal Mac keyboard when you’re using Sidecar. The iPad keyboard can enter text into any active window, including the ones on your Mac’s native displays; the only difference is that function keys on the iPad’s keyboard (volume and media playback controls, Back and Home buttons, and so on) still control the iPad, not the Mac. So you can put text into any window you want, but if you’d like to adjust the Mac’s volume you’ve got to do it with a mouse or trackpad or with the keyboard connected to the Mac directly.

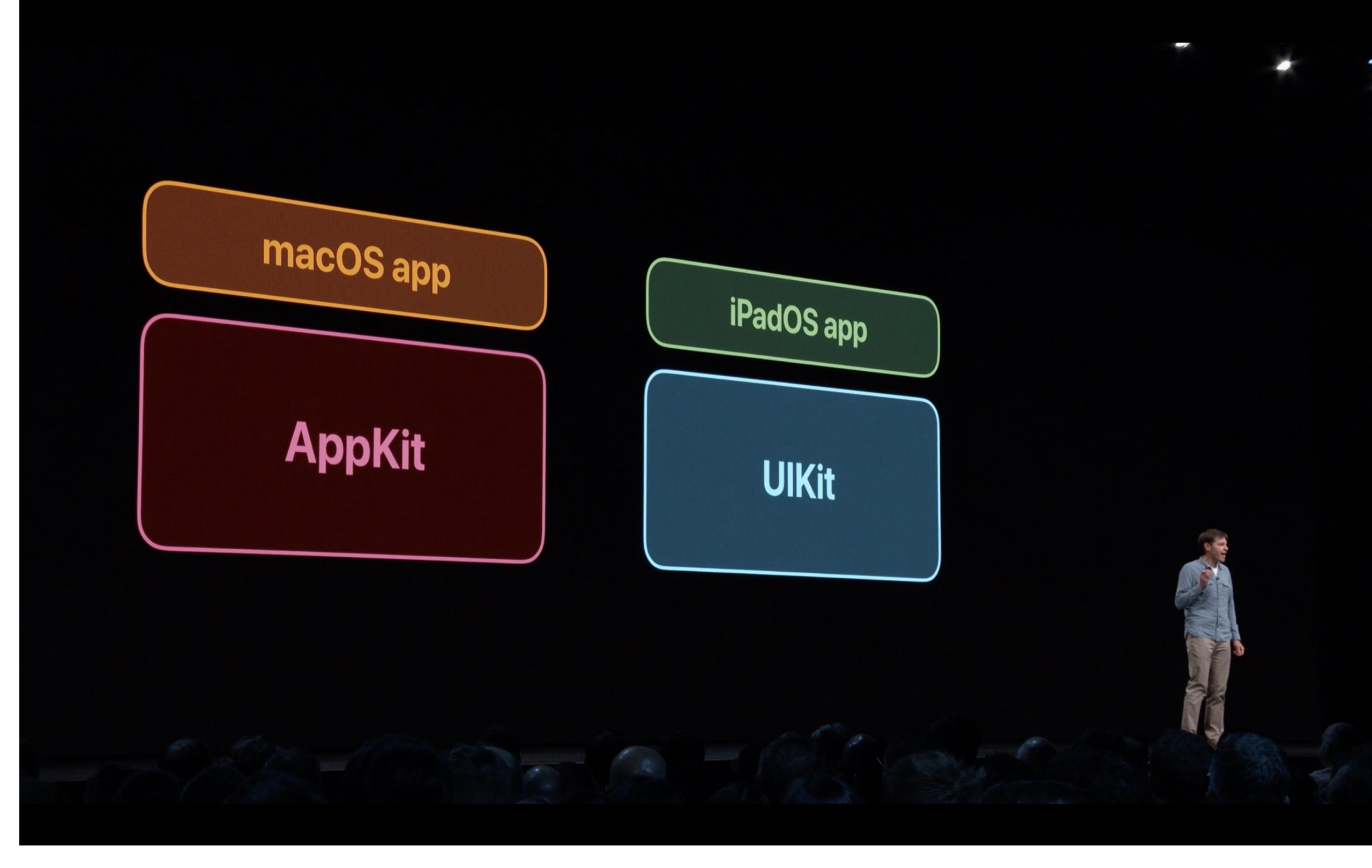

Catalyst: iPad apps come to the Mac

Apple talks about iPad apps on the Mac at WWDC 2019. Credit: Apple

“Catalyst” is the official, public name for the collection of technologies that will allow developers to port their iPadOS apps to the Mac (you may know it as “Marzipan,” which was widely reported as the internal codename for the project). We covered an earlier version of Catalyst in our Mojave review, since Apple previewed the technology by porting a small number of first-party iOS apps (News, Stocks, Voice Memos, and Home) to the Mac. We’ll cover the changes to those apps later—here, we’ll just focus on the changes to the foundational technology.

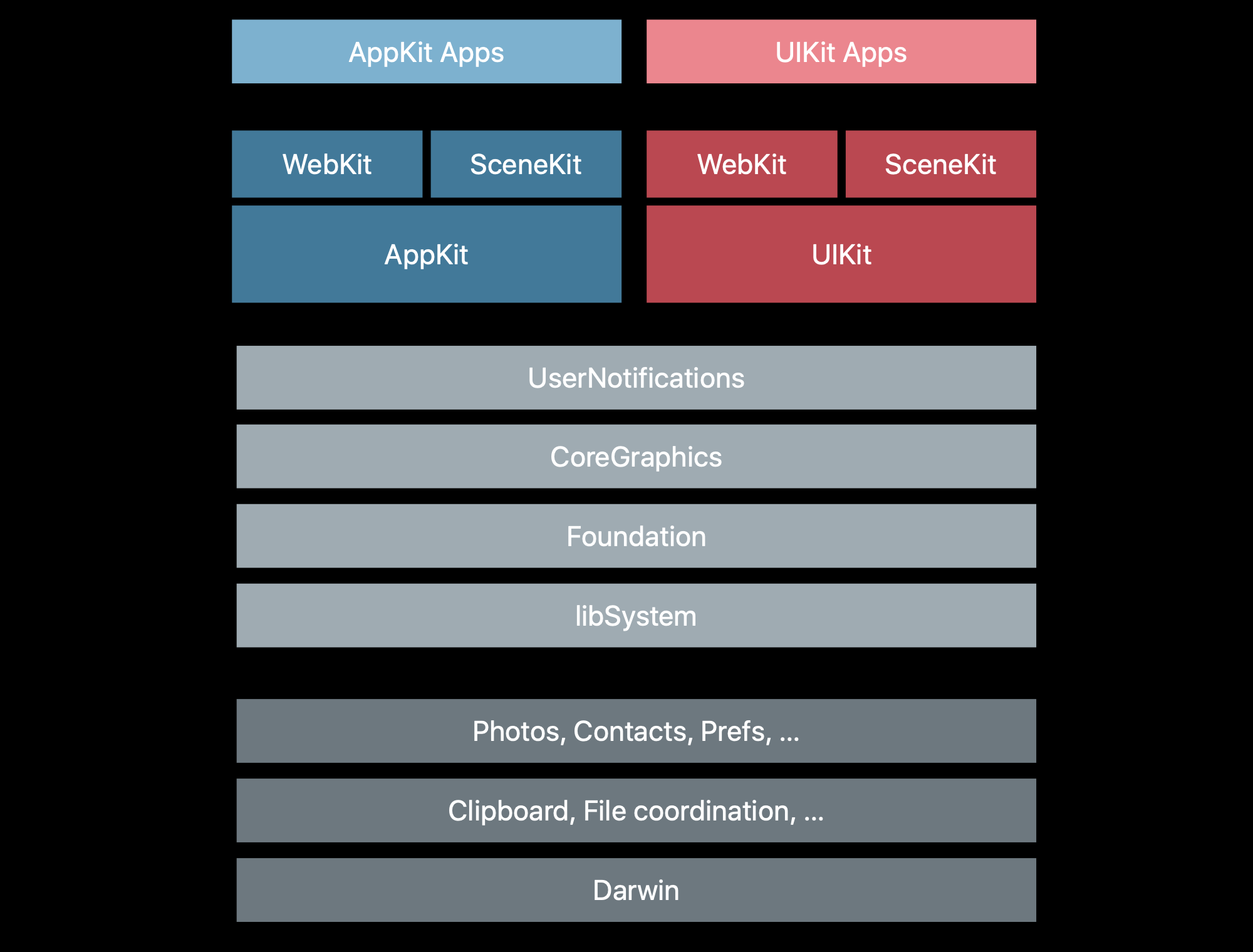

To recap, Catalyst works by mapping certain behaviors from UIKit, which is used to build iOS and iPadOS apps, to AppKit, which is used to build Mac apps. Using Catalyst, an app that already knows how to handle taps and swipes from a finger can in many circumstances automatically be adapted to handle clicking and scrolling from a trackpad. Apps can also take advantage of things like the menu bar and additional windows, things that are available on a Mac but not on iPads.

Note that Apple is specifically bringing iPad apps to the Mac, not iOS apps. If you’ve ever tried using most Android apps on a Chromebook (or a tablet, though Android tablets have been effectively dead for a while now), you know why you don’t want to run an app designed for a narrow, primarily vertical phone screen on a wide, primarily horizontal laptop screen. Modern iPad apps are, in theory, already designed to take advantage of landscape mode, and (if they support Split View) they’re already capable of dynamically adjusting how content is presented as you resize windows. You might still run into excessive whitespace and odd layouts if you’re using an iPad app full-screen on a 27-inch iMac, but on the vast majority of 13-inch laptop screens things won’t look bad.

Apple has done a bit of backend work in Catalina to make it more difficult to tell a UIKit app from an AppKit app. Launching the UIKit-based apps in Mojave spun up multiple processes in Activity Monitor, one “host” app and then the actual UIKit app that would be launched by the host app. Catalyst apps in Catalina just use a single process, which enables a slightly more seamless interaction between UIKit and AppKit code (developers can’t mix-and-match UIKit and AppKit, but apps can include separate AppKit bundles that do Mac-specific things that UIKit can’t handle). And Catalyst apps can continue running in the background once all their windows have been closed (though some apps still behave this way, going against decades of established Mac app behavior).

Most Catalyst apps still have clear tells, like the iOS-style dialog boxes and time picker in the Home app or the un-Mac-like pop-up menus in the Podcasts app. But Podcasts shows how the Catalina Catalyst apps can look and feel more like AppKit apps—the Music app is built on AppKit and Podcasts is built on UIKit, but at a glance the interfaces are really similar. As developer Steve Troughton-Smith notes, it can be “hard to tell the difference without disassembling” the apps to see what framework they’re actually using. Catalyst apps can even be distributed outside the Mac App Store, just like “real” Mac apps.

The downside to these improvements is that Catalyst apps will only run on Catalina—Apple isn’t backporting anything to Mojave or older versions of macOS. And It remains to be seen how forward and backward compatibility will work in future versions of macOS. Will Catalyst apps released today still work without modification in macOS 10.16, since it will presumably include iPadOS 14 features and its own modifications to the underlying Catalyst technology? Will Catalyst apps targeted toward macOS 10.16 be able to work on Catalina Macs? Per usual, Apple isn’t talking about its future plans that far in advance.

What developers are saying

Apple has talked up partnerships with established companies like Twitter and TripIt, who previewed their Catalyst apps at WWDC and spoke to Ars afterward to walk us through the process of porting an iPad app over to the Mac. For this review, I also spoke with multiple indie developers to try to get a better sense of how Catalyst was being received now that it had been available to play with for a few months.

If you’re a developer, whether you’re interested in Catalyst depends a lot on what apps you’ve already got. Developers with iPad apps who wanted to get an app on the Mac with relatively minimal effort are the main audience for Catalyst, and a bunch of apps in this vein should be available on or near day one. This includes apps like Twitter, TripIt, and GameLoft, and art apps like Vectornator, and productivity apps like Zoho Books, Post-It, and Good Notes. Developer Steve Troughton-Smith has a good Twitter thread of other independently developed Catalyst apps, too.

But Mac developers who already maintain AppKit apps are, by and large, happy to continue maintaining separate apps for the time being, and they are in no particular rush to unify their codebases. These developers are either staying away from Catalyst entirely (at least for the time being) or using it to experiment with smaller, simpler apps instead.

Catalyst lets iPadOS apps developed with UIKit run on the Mac alongside traditional Mac apps built using AppKit. Credit: Apple

Max Seelemann is the executive director of Ulysses, a Markdown-based text editor that currently offers similar-but-separate apps for the Mac, the iPad, and the iPhone. He said that while relatively simple iPad apps are pretty easy to translate, in most cases complex AppKit apps cannot easily be replaced by Catalyst versions.

“As long as an app has a lot of default components, default layout and default interactions on iPad, those will map well into default Mac behaviors and looks. As soon as an app starts to get complex and you customize things, Catalyst will likely become more of a roadblock,” Seelemann said. “There is a long list of gaps—it’s essentially everything that isn’t conceptually at home on iPad. Think of three-column split views, detachable popovers, the recently opened files menu, Time Machine file history browsing, etc. Some of these are doable with a lot of effort; some are just impossible without leaving the Catalyst APIs.”

James Thomson, developer of the cross-platform app PCalc, told me that he is planning to maintain the separate UIKit and AppKit versions of PCalc. But he is using Catalyst to port over a version of his smaller, previously-iOS-only 3D dice rolling app called Dice. He’s been generally impressed by the technology, and the developer points out that it has benefits even for iOS developers who don’t want to make Catalyst apps.

“They have done an awful lot to get it this far. A lot of the core code just works seamlessly,” Thomson said. “For example, one thing that has been difficult up until Catalina, is that 3D graphics haven’t been well supported in the simulator. So if you use Metal, or the advanced features of SceneKit, they haven’t worked. Which made development somewhat harder, because you always had to run your code on a real device. Now, not only is Metal supported in Catalyst apps, but it’s also available in the simulator. Which will make my day-to-day development work easier.”

Game developers don’t seem particularly interested in Catalyst at this point, though it’s certainly possible to port iOS games over to macOS using the technology (a couple months back, we spoke to developers at Gameloft Barcelona about Asphalt 9: Legends, one of the early Catalyst apps that Apple showed off at WWDC). Multiple developers indicated to me that middleware engines like Unreal and Unity already make it relatively easy to get games running across different platforms.

“Engines do most of the heavy lifting for cross-platform work already,” said Peter Curry, one of the cofounders of Mini Motorways and Mini Metro developer Dinosaur Polo Club. “A lot of what Catalyst does for developers (converting native UIKit views from iPadOS to macOS equivalents) aren’t useful for games as they don’t tend to use the native UI toolkits.”

Another possible Catalyst roadblock might currently be Apple’s documentation on the feature—namely, that there isn’t a whole lot of it. PCalc’s Thomson cited a few specific examples, echoing concerns I had seen among developers on Twitter.

“I think a lot of documentation effort has gone on things like SwiftUI, and not on Catalyst. A lot of the new Catalyst-only APIs, like the menu support, don’t really have any documentation at all,” Thomson said. “It’s not always difficult to work out, but with some things like how the new multiple-window API from the iPad translates to the Mac, I’ve run into problems where I don’t know if I’m hitting bugs, or I’m just doing it wrong. There’s very little discussion on the Apple developer forums or on the likes of Stack Overflow. Some developers have been discussing things on Twitter, and swapping tips there, and that’s been the best source of information. It does feel a bit like we’re treading unexplored ground.”

SwiftUI (or, the future of cross-platform apps)

If Apple has devoted more time to documenting SwiftUI than Catalyst, it’s because SwiftUI is probably going to be the more impactful technology for most developers going forward.

SwiftUI isn’t a complete replacement for AppKit or UIKit (or the tvOS version of UIKit, or the Apple Watch’s WatchKit). But it will give developers a way to write code one time and have that code displayed differently in different operating systems based on what looks and works best on each. A chunk of code that generates a drop-down menu or a radio bubble on macOS might generate a scrollable picker in iOS or iPadOS; a list of options in an iOS app might be transformed into a strip of Touch Bar controls on a Mac. With SwiftUI, developers can write platform-specific code on top of that connective tissue, optimizing their apps for each operating system’s strengths and weaknesses.

Seelemann believes that Catalyst is “transitional” technology and that SwiftUI is more forward-looking and flexible.

“SwiftUI’s big benefit over Catalyst is its composability,” he told Ars. “You can write the parts of an app that are identical between platforms in SwiftUI and then combine it with native elements where necessary. While with Catalyst one API designed for touch and mobile has to cover all cases even of a desktop interface, SwiftUI allows you to pick what’s best for each area.”

Apple pointedly doesn’t say that developers should just write one app that looks and acts the same across all operating systems, just like making a good Catalyst app requires more work than just checking a box in Xcode. And developers can adopt SwiftUI code alongside UIKit and AppKit code, just as they can add chunks of Swift code to an existing Objective-C app.

“While Catalyst is all-or-nothing, SwiftUI can be added gradually to existing Mac and iOS apps,” Seelemann said. “This will allow us to be more efficient and faster when adding new features beginning as soon as next fall.”

But the Swift example is instructive. SwiftUI is brand-new, which means that it’s not going to be capable of everything that AppKit and UIKit can do, and Apple is likely to make substantial changes every year for at least a few years. That means that, though developers do seem interested in SwiftUI and willing to try it out for new projects, most of them probably won’t go all-in on it until it’s more predictable.

“SwiftUI is younger than Catalyst as technology, and I expect possibly more updates for it next year,” said Danilo Bonardi, a developer at Shiny Frog who works on the cross-platform Bear text editor. “I can see it adopted as the way to go for the iOS development in 1 or 2 years, but Bear comes with a considerable UI codebase, and I don’t see us migrating to SwiftUI soon.”

This sense of caution leaves room for Catalyst’s melding of AppKit and UIKit to serve developers who want to get their iPad apps on the Mac, while at the same time giving developers with existing AppKit apps a reason to wait before overhauling their codebases.

All of this is to say, we are moving slowly toward a future where iOS, iPadOS, and macOS can all run a lot of the same apps, which will hopefully be to each platform’s benefit. But it’s going to be a slow, multi-step, multi-year process, and developers have a lot of reasons to wait and see how Apple’s various tools mature as the company responds to developer feedback. The Mac and the iPad are not going to reach application parity overnight.

iTunes no more: Music, Podcasts, and TV

There’s nothing Apple makes that people enjoy complaining about as much as iTunes (though the butterfly keyboard might come close). Most of that griping is well-earned. Over the years, iTunes has gone from local music player, MP3 store, and iPod-syncer to a gigantic, shambling piece of software that also handles Apple Music streaming, video and podcast downloads, iPhone and iPad updates and software management, and tons more. It’s impressive, in the sense that it has continued to add new stuff while still supporting the same basic local MP3 player/music store/iPod management that iTunes has handled for close to two decades. But it makes for an unwieldy piece of software, and it’s telling that iTunes’ core functionality is split up between five or six different apps on an iPhone or iPad, since Apple had the opportunity to rebuild everything from scratch for mobile.

Catalina splits iTunes’ core features out into four apps—Music, Podcasts, and TV handle the media stuff, while the Finder takes over management, system restores, and backups of iPods, iPhones, and other devices. Apple says iTunes will continue to exist as it currently is on Windows, and presumably the iTunes versions on older-but-still-supported macOS releases will continue to receive updates to fix security holes and keep them compatible with Apple’s media stores and streaming libraries. Apple has published a support document detailing the transition from iTunes to all these separate apps, but we’ll cover the basics here (with an emphasis on people who have been using iTunes for a long time to handle all their media, not just people who use it as a streaming client for Apple Music).

Music

Apple Music looks and works largely like it did before. Andrew Cunningham

Music is the app that comes the closest to being as complex and overloaded as iTunes was, and it actually does appear to be an AppKit app based on the same codebase as iTunes (the icon is near-identical, too, though it trades its colorful outer ring for a soft white gradient). Music still pulls triple duty as a local music library manager and CD ripper, a music store where you pay once for music files and music videos that you can then download forever (still called the “iTunes Store,” one of the few places where the old name appears to survive), and a client app for the a la carte Apple Music streaming service. It benefits from shedding the features it does lose, but there’s still a lot going on here.

Music puts Apple Music front-and-center rather than tacking it on to a manager for a local media library—the first time you open it, you’ll be asked to subscribe to Apple Music if you haven’t already, same as in Music on iOS. By default, Catalina doesn’t even offer access to the iTunes Store in the app’s sidebar, regardless of whether you’re using a fresh install or a library imported over from the Mojave version of iTunes. Head to Preferences and check the box to restore the iTunes Store and its familiar interface, including ads for new releases, curated lists, and charts.

The good news for anyone with an extensive, carefully curated iTunes library is that you’d be hard-pressed to identify any longstanding iTunes features that Apple has actually removed. Everything in the library I tested with survived an upgrade install from Mojave to Catalina, including all your metadata, old playlists, synced iCloud Music Library files, and even both versions of the old iTunes visualizer (if you spent any time in a college dorm in the early-to-mid 2000s, you are definitely familiar with the classic visualizer).

Some of those features are admittedly a bit buried, though. For example, Catalina still includes everything you need to enable classic iTunes library sharing, but it’s not available in the Music app’s preferences. Enabling library sharing is now handled from the new “Media Sharing” section in the Sharing preference pane of System Preferences. And accessing shared libraries is now hidden behind a drop-down menu, accessible by clicking the small arrow next to “Library” in the Music app’s sidebar.

Once you’ve found where everything is, though, there’s surprisingly little to say about the Music app, because the local library features and the Apple Music features all work just as they did before. Apple Music is more strongly emphasized than ever, but that shouldn’t surprise anyone—streaming is just the way that most people listen to most of their music now. But the fact that all of these other features, even the moved and hidden ones, survived the Great iTunes Divorce Proceeding of 2019 indicates that Apple wants to keep longtime iTunes users’ libraries intact. Upgrading your operating system, at least for now, doesn’t need to totally upend your listening habits.

Behind the scenes, the way your music library is stored has changed a bit. iTunes used a few different files to keep track of all your stuff; the main iTunes Library.itl file kept track of play counts, star ratings, and other stuff external to song metadata; album artwork and your actual songs were both kept in their own folders; and a couple of .itdb database files kept track of Genius playlists and “extras.”

Music sticks most of the non-music-file data into a single Music Library package, which contains those .itdb files plus a bunch of files with a new “.musicdb” extension to keep track of library data and other preferences. If you upgrade your iTunes library, your media is still stored in a folder labeled “iTunes.” If you import songs into a new library on a fresh Catalina install, they’re imported into a Media folder with the same file structure as the old iTunes folder. None of this really affects the way your library looks or plays in the Music app itself—it’s just a sign that Apple is rethinking the way your music is stored in addition to breaking iTunes up into separate apps.

Some apps that relied on the old iTunes library format may be broken until developers can issue fixes for Catalina; many DJ apps, for example, could read iTunes’ XML-based library files but can’t be used with Catalina’s Music app without updating. As always, check your important apps and make sure they officially support Catalina before updating.

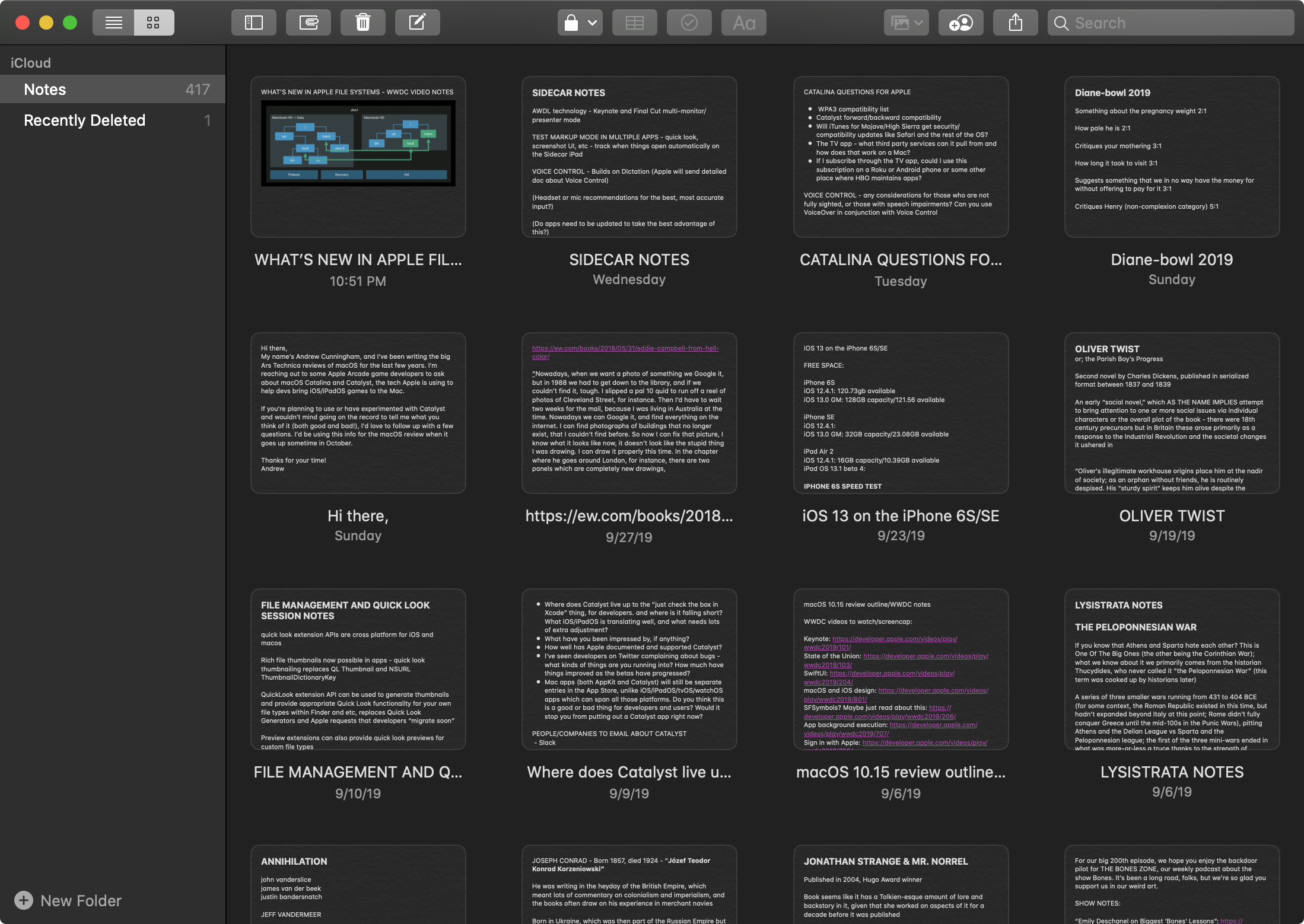

Podcasts

Podcasts is a UIKit app, making it less a direct descendant of iTunes and more a Catalyst port of the existing Podcasts app on the iPad. Like the other first-party Catalyst apps, the Mac Podcasts app is laid out in the same basic way as the iPad app—the Listen Now page shows new episodes of podcasts you’ve subscribed to, the Library page shows all the shows you subscribe to and gives you a few different sorts options for them, and the Browse section is a combination of curated lists as well as popular shows.

But the app has been tweaked to make it more Mac-like, and visually it still intentionally evokes the iTunes interface. The playback controls and progress bar are situated at the top of the window and not the bottom, and a persistent sidebar (and always-present search bar) exposes all of your navigation options at once rather than hiding them behind multiple taps as the iPad app does.

Downloaded podcast episodes no longer appear in your iTunes library folder but in a more hidden cached folder at ~/Library/Group Containers/243LU875E5.groups.com.apple.podcasts/Library/Cache with an abstracted name that will prevent the file from showing up in a Spotlight search.

TV

If you’ve bought movies and TV shows through iTunes, the TV app is where you’ll go to find them. If you’ve seen this app on an iPhone, iPad, or Apple TV, you know what to expect here, though the version you get in macOS is inferior to the one on Apple TV and iDevices—not because the interface has changed, but because the way it pulls from third-party sources is different. The Mac’s version of the app has more in common with the version that Apple will be releasing for third-party hardware like the Fire TV, Roku, and other smart TVs than with the iOS and tvOS version of the app.

On the Apple TV or an iDevice, the TV app can see any compatible streaming app you have installed (HBO Now, PBS Kids, Hulu, and a host of others), and it will offer content available through those services. The Mac app offers a more limited subset of “Apple TV channels,” which include “HBO, Showtime, Starz, and more.” These channels, which offer subscriptions through the TV app, don’t require additional apps or logins, and (aside from some logo placement) they blend in with Apple’s iTunes Store offerings (and, soon enough, the original programming that Apple’s ludicrously large pile of cash is paying for).

Episodes from these channels can even be downloaded for offline viewing, the same as episodes you’ve paid for individually in the iTunes Store. All episodes are downloaded to your Movies folder as MP4-encoded HLS video files delivered in a bundle with a .movpkg extension. This bundle contains hundreds of tiny video files—normally you’d stream these from a server somewhere, downloading them in real-time as you watch the video. The .movpkg format just allows you to “stream” them locally, without a connection. The file can be played by the TV app itself but not by QuickTime; third-party players may be able to play parts of the video but not the important DRM-protected bits. For example, VLC could play the opening HBO advertisement from a Game of Thrones episode I downloaded, but it would freeze up before playing the episode itself. This is more or less how Apple handles DRM and offline playback for things downloaded from Apple Music.

Offline downloads are definitely a value-add for the TV app, since many of these providers’ own apps don’t allow it. The downside is, these channels work only in Apple’s TV app. If you have an existing HBO Now subscription, even if it’s already through iTunes, this won’t buy you access to HBO shows through this version of the TV app. (If you subscribe to both simultaneously, the Apple TV version is described as “HBO on Apple TV.”) And unlike subscriptions to other services purchased through Apple, you don’t have a login that will work in those providers’ own apps. Pay for HBO through the TV app, and you can only view HBO shows on other platforms with an Apple TV app, not any platform where HBO offers an HBO Now app.

This means that if you’ve got an existing Apple TV that’s set up with all of these services and you want to switch over to using Apple TV channels so you can watch stuff on the Mac or on that subset of third-party devices, you’ll need to unsubscribe and then re-subscribe through the TV app. That Apple doesn’t offer an easier, more automated way to do this, and that it’s not even immediately clear that this is what is happening unless you do some digging and try it yourself, makes for an uncharacteristically rough and annoying experience. I’m sure it has something to do with limitations imposed by content providers—the ability to offer downloads seems likely to come with distribution restrictions. But it seems engineered to tempt people to switch from using independent subscriptions (which Apple may or may not receive a cut of) to using subscriptions bought exclusively through Apple (which the company does receive a share of).

Long story short, I’m sure the TV app on the Mac will be a fine client for Apple’s own TV service, and it’s a decent portal to the video arm of the iTunes Store. But as a client for third-party streaming services—even compared to the versions of the same app on Apple’s other platforms—it falls short.

Syncing with Finder

At this point, most people have probably stopped connecting their iPhones and iPads to a computer running iTunes to install software updates or sync media or data (at this point, it’s weird to even think about needing to plug a new phone or tablet into a computer before you could start using it). But Internet-free iPods still exist. Devices still fail, putting them into recovery mode. Local backups are still useful if you don’t want to pay for extra iCloud space, or if you don’t want your device backups on Apple’s servers. People with local media libraries may still want to manage them manually, to give them some sense of control in a world that resists all efforts to impose order upon it. For all of those people, the Finder adopts most of the device management and syncing features that used to live in iTunes.

The Finder is a whole lot less annoying about it, which is nice—plugging an iPhone into a Mac would automatically launch iTunes, even if all you wanted to do was charge your phone, but a Catalina Mac treats an attached iPhone a bit more like a USB drive. It shows up in the Finder sidebar and in a few other apps, but it doesn’t automatically launch anything anymore (aside from the typical “trust this device” prompts you need to click through to confirm that you do in fact want your Mac to be able to talk to the phone in the first place).

The main device info screen in the Finder looks mostly like the same screen looked in iTunes, giving you information about the device, what software it’s running, how much storage is available, and what’s using that storage. You can update, restore, and backup the device with a few clicks, much like you could before. Tabs are available for each kind of file that can be stored on your phone, condensing screens that were still separate in iTunes under Mojave—your sync settings and all the files available for syncing live in the same tab now. iDevices still show up in the sidebars of the Music and TV apps but only to show you what media you’ve already synced to your phone. Clicking the Sync Settings button in either app just kicks you back to the Finder.

As with iTunes, Apple has made an admirable effort not to get rid of old functionality. Older, pre-iOS 13 iPhones and even old iPods can still be updated, wiped, and managed with Finder, just as they could in iTunes.

Other apps: Find My

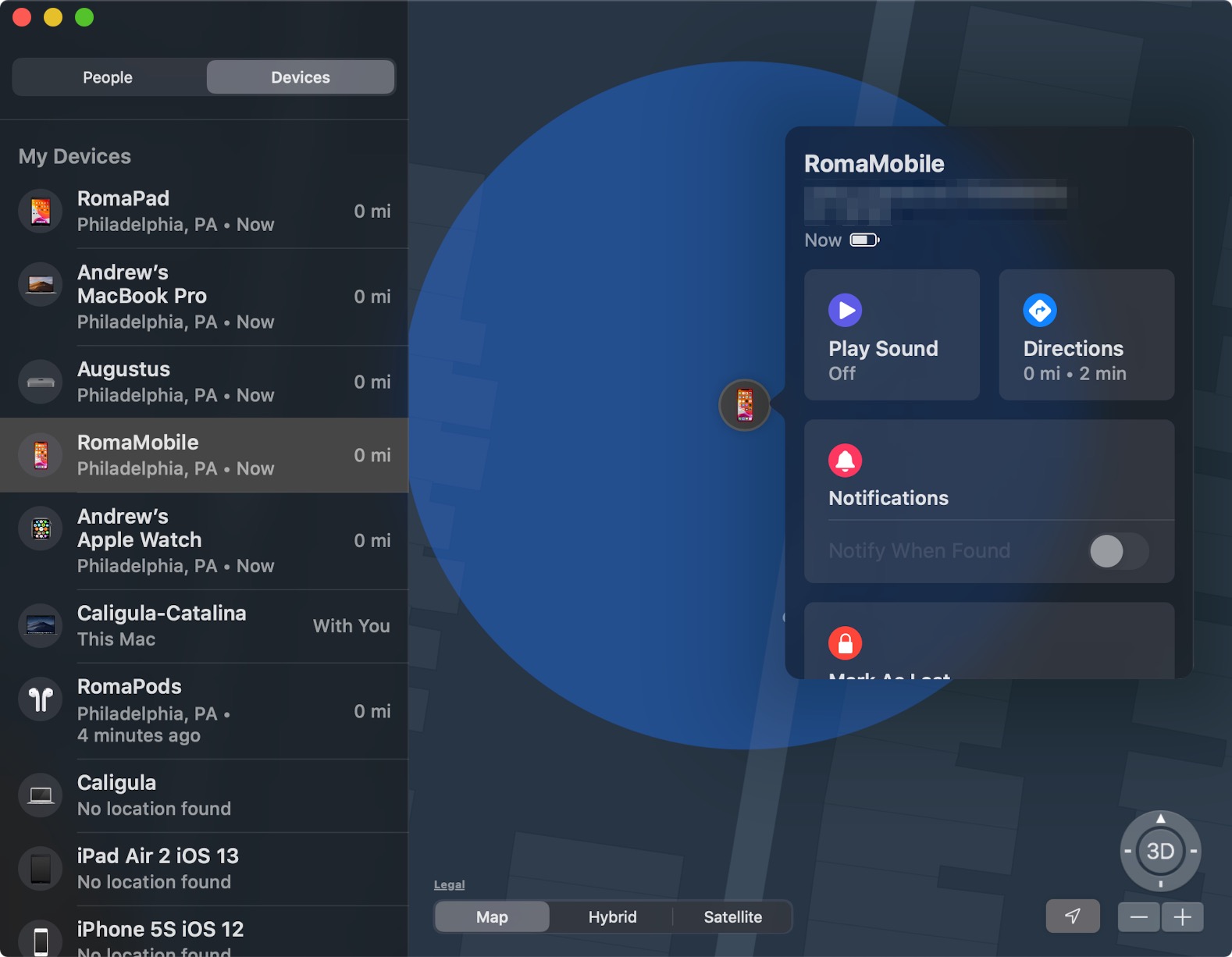

Find My is one of Catalina’s new first-party Catalyst apps. It combines the functionality of the old iOS Find My Friends app with the Find My iPhone app, with a more Mac-like sidebar and pop-over menus. Credit: Andrew Cunningham

Find My is one of the Mac’s new first-party Catalyst apps, and it’s a lot like the version of the same app that comes in iPadOS 13. Like its iPad and iPhone counterpart, the Mac Find My app combines the person-tracking features of the old Find My Friends app with the device-tracking features of the Find My iPhone app.

When you’re viewing your friends’ locations, Find My shows you where they (or the iDevice they share their location from) were and when their device was seen last. You can share your own location with other people, but unlike in the iPhone and iPad versions of the app, you can’t share your location from your Mac. Your position in Find My still needs to be determined by an iDevice, presumably because they’re designed to be connected to something all the time, and your Mac is more likely to be disconnected if you’re traveling with it.

Finding devices works exactly as it does in iOS or iPadOS—the Find My app will show you the last known location of any device you or one of your family members has signed into and what its last-known battery status was. You can play a sound to locate a lost device, get directions to a device’s location, enable notifications to let you know when a missing device comes back online, and mark devices as lost to lock and wipe them remotely if they ever come back online.

In both People and Devices modes, Find My uses Apple Maps to show you where everything is, so you see all the same locations labeled in the same ways. And you’ve got the same view options, too—the default Map view, the realistic Satellite view, and the in-between Hybrid view. The default top-down view can also be toggled to 3D mode to show a rough approximation of the landscape, in areas where that feature is available.

Aside from the inability to share your Mac’s location, the Find My app in macOS showcases some of the things Apple is doing to make Catalyst apps feel a bit more Mac-like. The Mac version of the app has a persistent sidebar that always spans the left edge of the window, where the iPad version has a floating menu that expands and contracts as you interact with it. And when you click on a person or device, extra information pops up in a separate pane without changing the information available in a sidebar, an acknowledgement that most Macs will have more screen space to work with than most iPads.

Reminders

The new Reminders app has a few smart lists that gather reminders from all your lists based on timing and priority. Andrew Cunningham

Reminders is the rare app to get a substantial redesign for Catalina instead of just being tweaked—the update is big enough that you even need to upgrade your reminders to be compatible with the new app. If you’ve installed iOS 13 and/or iPadOS 13 on your devices already, you may have unexpectedly upgraded your reminders, breaking compatibility with your Mac in the process (as well as any devices on older versions of iOS, iPadOS, or macOS).

The very first Mac version of the Reminders app was designed to resemble a notepad or day planner, and the version in Mojave was mostly a flattened version that removed the visual skeuomorphism without really rethinking the conceptual skeuomorphism (as was the case with many iOS 7 and Yosemite-era app redesigns). The Catalina version, like the iOS 13 version, includes a few automatically generated smart lists plus new buttons that make it easier to add dates, locations, and flags to all of your reminders. The old “individual lists full of items” format is still there, but the new format makes it easier to make common changes to reminders rather than hiding it all behind a right-click or the information button.

In addition to suggesting possible dates and locations as you’re typing a new reminder, the app will periodically make suggestions based on what you’re typing. Putting down “remind me at 9am,” for instance, prompts the app to ask you whether you mean 9am tomorrow and offers to set that date for you; type “remind me every week” and the app will offer to create a recurring reminder. Click the info button next to a reminder and you can associate it with a person in your contacts list so that the app shoots you a notification next time you’re communicating with that person in Messages—adding URLs and images to reminders is an option now, too.

Any iCloud lists of reminders can now be shared with other iCloud users using an interface similar to the one used for sharing Notes. The old app could share lists with other officially designated family members associated with your account, but that has been removed in the name of additional flexibility—sharing lists with your family members is now the same as sharing them with anyone else.

Reminders does still support lists from external accounts, even though the “Accounts” item in the menu is gone. External accounts benefit from the new styling and arrangement of buttons but otherwise don’t appear to be improved, downgraded, or otherwise impacted—all of the improvements above only apply to iCloud-based reminders, and reminders from third-party services are still pretty basic.

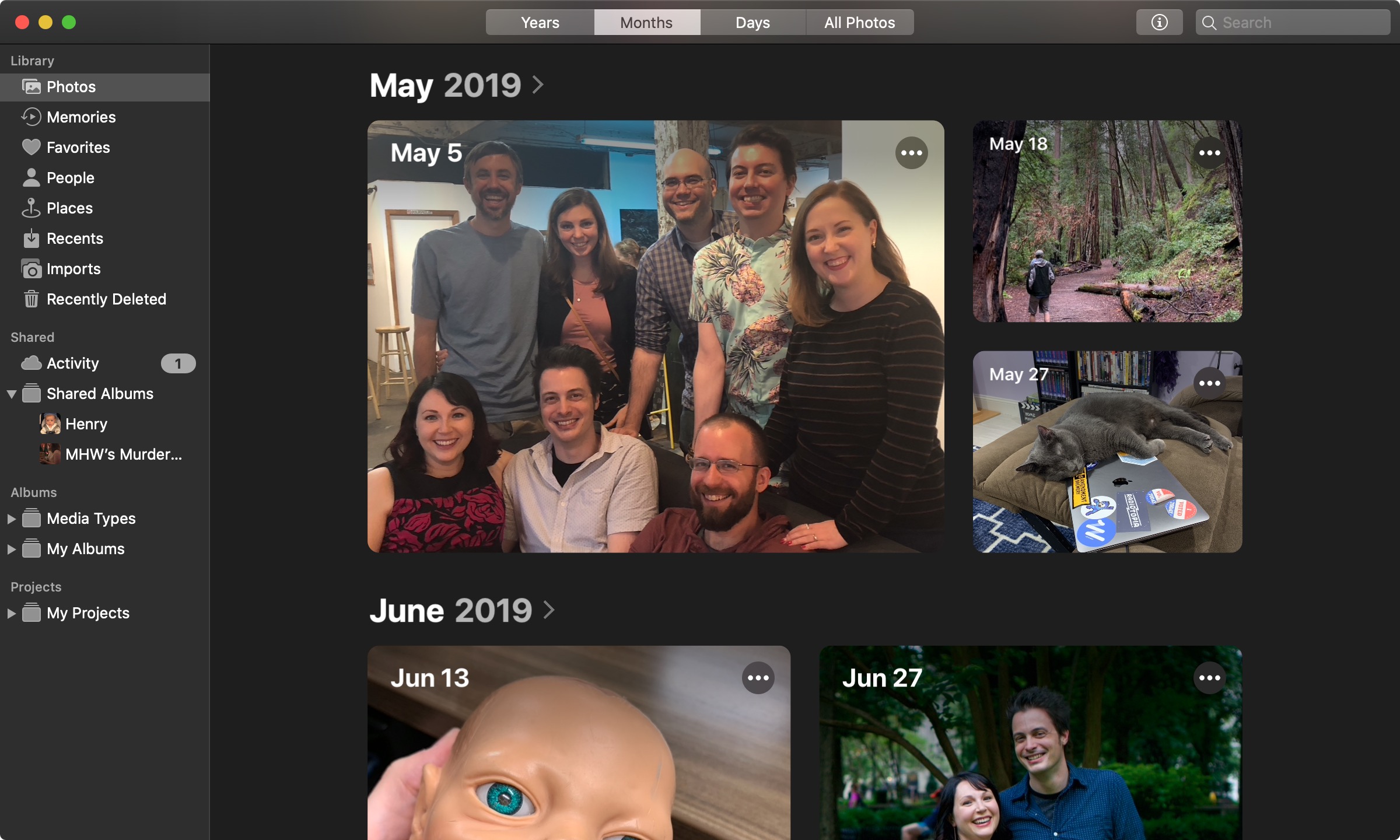

Photos

The Photos app gets less ambiguous time-based top-level sorting options, plus a new UI that tries to do a better job of showing your representative pictures. Credit: Andrew Cunningham

The tweaks to the macOS version of the Photos app are minor and mostly organizational. The default view of your Photos library has been re-labeled to make it less ambiguous. In Mojave, the Photos tab showed you all of your pictures and videos in reverse-chronological order, and the All Photos tab in Catalina does essentially the same thing.