As the industry continues to grapple with the Meltdown and Spectre attacks, operating system and browser developers in particular are continuing to develop and test schemes to protect against the problems. Simultaneously, microcode updates to alter processor behavior are also starting to ship.

Since news of these attacks first broke, it has been clear that resolving them is going to have some performance impact. Meltdown was presumed to have a substantial impact, at least for some workloads, but Spectre was more of an unknown due to its greater complexity. With patches and microcode now available (at least for some systems), that impact is now starting to become clearer. The situation is, as we should expect with these twin attacks, complex.

To recap: modern high-performance processors perform what is called speculative execution. They will make assumptions about which way branches in the code are taken and speculatively compute results accordingly. If they guess correctly, they win some extra performance; if they guess wrong, they throw away their speculatively calculated results. This is meant to be transparent to programs, but it turns out that this speculation slightly changes the state of the processor. These small changes can be measured, disclosing information about the data and instructions that were used speculatively.

With the Spectre attack, this information can be used to, for example, leak information within a browser (such as saved passwords or cookies) to a malicious JavaScript. With Meltdown, an attack that builds on the same principles, this information can leak data within the kernel memory.

Meltdown applies to Intel’s x86 and Apple’s ARM processors; it will also apply to ARM processors built on the new A75 design. Meltdown is fixed by changing how operating systems handle memory. Operating systems use structures called page tables to map between process or kernel memory and the underlying physical memory. Traditionally, the accessible memory given to each process is split in half; the bottom half, with a per-process page table, belongs to the process. The top half belongs to the kernel. This kernel half is shared between every process, using just one set of page table entries for every process. This design is both efficient—the processor has a special cache for page table entries—and convenient, as it makes communication between the kernel and process straightforward.

The fix for Meltdown is to split this shared address space. That way when user programs are running, the kernel half has an empty page table rather than the regular kernel page table. This makes it impossible for programs to speculatively use kernel addresses.

Spectre is believed to apply to every high-performance processor that has been sold for the last decade. Two versions have been shown. One version allows an attacker to “train” the processor’s branch prediction machinery so that a victim process mispredicts and speculatively executes code of an attacker’s choosing (with measurable side-effects); the other tricks the processor into making speculative accesses outside the bounds of an array. The array version operates within a single process; the branch prediction version allows a user process to “steer” the kernel’s predicted branches, or one hyperthread to steer its sibling hyperthread, or a guest operating system to steer its hypervisor.

We have written previously about the responses from the industry. By now, Meltdown has been patched in Windows, Linux, macOS, and at least some BSD variants. Spectre is more complicated; at-risk applications (notably, browsers) are being updated to include certain Spectre mitigating techniques to guard against the array bounds variant. Operating system and processor updates are needed to address the branch prediction version. The branch prediction version of Spectre requires both operating system and processor microcode updates. While AMD initially downplayed the significance of this attack, the company has since published a microcode update to give operating systems the control they need.

These different mitigation techniques all come with a performance cost. Speculative execution is used to make the processor run our programs faster, and branch predictors are used to make that speculation adaptive to the specific programs and data that we’re using. The countermeasures all make that speculation somewhat less powerful. The big question is, how much?

Meltdown logo

Meltdown

When news of the Meltdown attack leaked, estimates were that the performance hit could be 30 percent, or even more, based on certain synthetic benchmarking. For most of us, it looks like the hit won’t be anything like that severe. But it will have a strong dependence on what kind of processor is being used and what you’re doing with it.

The good news, such as it is, is that if you’re using a modern processor—Skylake, Kaby Lake, or Coffee Lake—then in normal desktop workloads, the performance hit is negligible, a few percentage points at most. This is Microsoft’s result in Windows 10; it has also been independently tested on Windows 10, and there are similar results for macOS.

Of course, there are wrinkles. Microsoft says that Windows 7 and 8 are generally going to see a higher performance impact than Windows 10. Windows 10 moves some things, such as parsing fonts, out of the kernel and into regular processes. So even before Meltdown, Windows 10 was incurring a page table switch whenever it had to load a new font. For Windows 7 and 8, that overhead is now new.

The overhead of a few percent assumes that workloads are standard desktop workloads; browsers, games, productivity applications, and so on. These workloads don’t actually call into the kernel very often, spending most of their time in the application itself (or idle, waiting for the person at the keyboard to actually do something). Tasks that use the disk or network a lot will see rather more overhead. This is very visible in TechSpot’s benchmarks. Compute-intensive workloads such as Geekbench and Cinebench show no meaningful change at all. Nor do a wide range of games.

But fire up a disk benchmark and the story is rather different. Both CrystalDiskMark and ATTO Disk Benchmark show some significant performance drop-offs under high levels of disk activity, with data transfer rates declining by as much as 30 percent. That’s because these benchmarks do virtually nothing other than issue back-to-back calls into the kernel.

Phoronix found similar results in Linux: around a 12-percent drop in an I/O intensive benchmark such as the PostgreSQL database’s pgbench but negligible differences in compute-intensive workloads such as video encoding or software compilation.

A similar story would be expected from benchmarks that are network intensive.

Why does the workload matter?

The special cache used for page table entries, called the translation lookaside buffer (TLB), is an important and limited resource that contains mappings from virtual addresses to physical memory addresses. Traditionally, the TLB gets flushed—emptied out—every time the operating system switches to a different set of page tables. This is why the split address was so useful; switching from a user process to the kernel could be done without having to switch to a different set of page tables (because the top half of each user process is the shared kernel page table). Only switching from one user process to a different user process requires a change of page tables (to switch the bottom half from one process to the next).

The dual page table solution to Meltdown increases the number of switches, forcing the TLB to be flushed not just when switching from one user process to the next, but also when one user process calls into the kernel. Before dual page tables, a user process that called into the kernel and then received a response wouldn’t need to flush the TLB at all, as the entire operation could use the same page table. Now, there’s one page table switch on the way into the kernel, and a second, back to the process’ page table, on the way out. This is why I/O intensive workloads are penalized so heavily: these workloads switch from the benchmark process into the kernel and then back into the benchmark process over and over again, incurring two TLB flushes for each roundtrip.

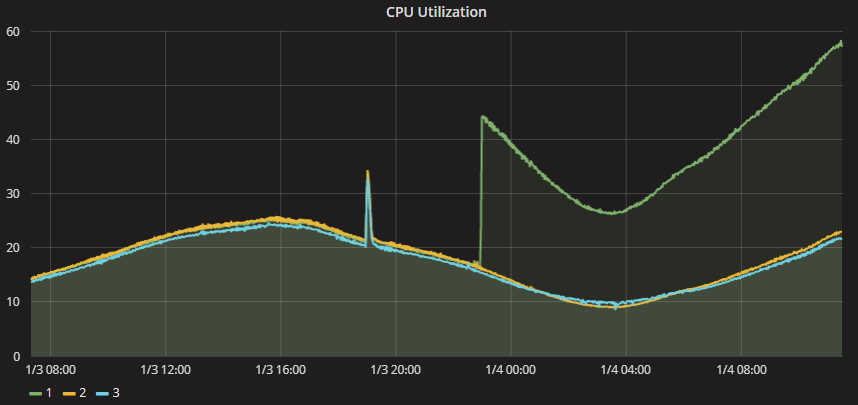

Credit: Epic

This is why Epic has posted about significant increases in server CPU load since enabling the Meltdown protection. A game server will typically run as on a dedicated machine, as the sole running process, but it will perform lots of network I/O. This means that it’s going from “hardly ever has to flush the TLB” to “having to flush the TLB thousands of times a second.”

The situation for old processors is even worse. The growth of virtualization has put the TLB under more pressure than ever before, because with virtualization, the processor has to switch between kernels too, forcing extra TLB flushes. To reduce that overhead, a feature called Process Context ID (PCID) was introduced by Intel’s Westmere architecture, and a related instruction, INVPCID (invalidate PCID) with Haswell. With PCID enabled, the way the TLB is used and flushed changes. First, the TLB tags each entry with the PCID of the process that owns the entry. This allows two different mappings from the same virtual address to be stored in the TLB as long as they have a different PCID. Second, with PCID enabled, switching from one set of page tables to another doesn’t flush the TLB any more. Since each process can only use TLB entries that have the right PCID, there’s no need to flush the TLB each time.

While this seems obviously useful, especially for virtualization—for example, it might be possible to give each virtual machine its own PCID to cut out the flushing when switching between VMs—no major operating system bothered to add support for PCID. PCID was awkward and complex to use, so perhaps operating system developers never felt it was worthwhile. Haswell, with INVPCID, made using PCIDs a bit simpler by providing an instruction to explicitly force processors to discard TLB entries belonging to a particular PCID, but still there was zero uptake among mainstream operating systems.

That’s until Meltdown. The Meltdown dual page tables require processors to perform more TLB flushing, sometimes a lot more. PCID is purpose-built to enable switching to a different set of page tables without having to wipe out the TLB. And since Meltdown needed patching, those Windows and Linux developers were finally given a good reason to use PCID and INVPCID.

As such, Windows will use PCID if the hardware supports INVPCID—that means Haswell or newer. If the hardware doesn’t support INVPCID, then Windows won’t fall back to using plain PCID; it just won’t use the feature at all. In Linux, initial efforts were made to support PCID and INVPCID. The PCID-only changes were then removed due to their complexity and awkwardness.

This makes a difference. In a synthetic benchmark that tests only the cost of switching into the kernel and back again, an unpatched Linux system can switch about 5.2 million times a second. Dual page tables slashes that to 2.2 million a second; dual page tables with PCID gets it back up to 3 million.

Those overheads of sub-1 percent for typical desktop workloads were using a machine with PCID and INVPCID support. Without that support, Microsoft writes that in Windows 10 “some users will notice a decrease in system performance” and, in Windows 7 and 8, “most users” will notice a performance decrease.

Spectre

Spectre logo

The Spectre story is, as ever, more complicated. Probably the most likely, widespread route of attack with Spectre is through a JavaScript running in a browser, using the array bounds version of Spectre to leak information about the browser to the JavaScript. This information might be directly valuable—for example, passwords and cookies—or it might be valuable for further exploitation. For example, the JavaScript could read information from the browser’s process and use that information to exploit other browser flaws and break out of its sandbox.

Significantly, this style of attack can’t be fixed with a kernel update. It needs at-risk applications to instead selectively guard at-risk tests of array bounds. If the array’s size and content isn’t directly controlled by end-users, then it may be safe, but if it’s controlled by potentially hostile user code, it will likely need to be protected against Spectre.

The team developing WebKit, used in Apple’s Safari browser, has written extensively about what they’re doing—and what the impact is. The general solution is to prevent the processor from speculating about whether it can access the array element or not. The solution that Intel and ARM have recommended is to insert a “serializing instruction” (one of a small selection of instructions that prohibits speculation around it) between testing the array’s size and accessing the array’s element.

Serializing instructions tend to be slow, taking potentially hundreds of cycles, so the WebKit developers have taken a different approach. Spectre attacks of this type try to access an element that’s wildly outside the bounds of the array; not just one or two bytes past the end, but gigabytes away. Accordingly, before accessing the array, WebKit first limits the index of the element being accessed to the next nearest power of two that’s larger than the size of the array. The developers have found that most processors won’t speculate across this type of operation, ensuring that they’ll wait for the bounds check, but without having to wait for the hundreds of cycles that serialization can impose.

As a defense in-depth measure, WebKit has also started using obfuscated memory addresses in certain data structures. This means that even if an attempt is made to speculatively access those addresses, the wrong address will be accessed, and if any of those addresses should be leaked to a malicious JavaScript, it won’t be useful. Microsoft has long used this technique in selective areas to defend against exploitable data leakage.

Taken together, the developers are currently seeing no measurable difference on the Speedometer Web benchmark and less than a 2.5 percent reduction in their JetStream scores. We’d expect other browsers to see a similar sort of hit. While this attack vector is troublesome, because it crops up in lots of places and can’t be fixed in any easy system-wide basis, the overheads of the fixes do appear reasonable.

Now the bad news

The branch predictor version of Spectre, however, is a different story. Microsoft warns that protecting against this specific problem “has a performance impact,” and, unlike the Meltdown fixes, this impact can be felt in a wider range of tasks.

There are a range of tools available to software and operating system developers. There are processor-level changes and a software-level change, and a mix of solutions may be needed. These new features also interact with other processor security features.

We have known since last week that Intel is going to release microcode updates that will change the processor behavior for this attack. With microcode updates, Intel has enabled three new features in its processors to control how branch prediction is handled. IBRS (“indirect branch restricted speculation”) protects the kernel from branch prediction entries created by user mode applications; STIBP (“single thread indirect branch predictors”) prevents one hyperthread on a core from using branch prediction entries created by the other thread on the core; IBPB (“indirect branch prediction barrier”) provides a way to reset the branch predictor and clear its state.

AMD’s response last week suggested that there was little need to do anything on systems using the company’s processors. That turns out to be not quite true, and the company is said to be issuing microcode updates accordingly. On its current processors using its Zen core—Ryzen, Threadripper, and Epyc—new microcode provides equivalents to IPBP and STIBP. On prior generation processors using the Bulldozer family, microcode has added IBRS and IBPB.

Zen escapes (again)

Ryzen die shot. Credit: AMD

Why no IBRS on Zen? AMD argues that Zen’s new branch predictor isn’t vulnerable to attack in the same way. Most branch predictors have their own special cache called a branch target buffer (BTB) that’s used to record whether past branches were taken or not. BTBs on other chips (including older AMD parts, Intel chips, ARM’s designs, and Apple’s chips) don’t record the precise addresses of each branch. Instead, just like the processor’s cache, they have some mapping from memory addresses to slots in the BTB. Intel’s Ivy Bridge and Haswell chips, for example, are measured at storing information about 4,096 branches, with each branch address mapping to one of four possible locations in the BTB.

This mapping means that a branch at one address can influence the behavior of a branch at a different address, just as long as that different address maps to the same set of four possible locations. In the Spectre attack, the BTB is primed by the attacker using addresses that correspond to (but do not exactly match with) a particular branch in the victim. When the victim then makes that branch, it uses the predictions set up by the attacker.

Zen’s branch predictor, however, is a bit different. AMD says that its predictor always uses the full address of the branch; there’s no flattening of multiple branch addresses onto one entry in the BTB. This means that the branch predictor can only be trained by using the victim’s real branch address. This seems to be a product of good fortune; AMD switched to a different kind of branch predictor in Zen (like Samsung in its Exynos ARM processors, AMD is using simple neural network components called perceptrons), and the company happened to pick a design that was protected against this problem.

In conjunction with these hardware features, a software technique called “retpoline” has been devised. This uses the hardware “return” instruction to perform indirect branches, rather than a more traditional “jump” or “call” instruction. Return instructions aren’t predicted using the branch predictor, so they aren’t prone to influence in the same way. Instead, there are separate return buffers that are used to predict return instructions. Using retpoline thus turns a possibly predicted branch with a possibly poisoned prediction into an unpredicted return.

Using retpoline for sensitive branches doesn’t work reliably on the latest (Broadwell or better) Intel processors, because those processors can, in fact, use the branch predictor instead of the return buffers. When returning from deep function nesting (function A calls function B calls function C calls function D…), the return buffers can be emptied. Broadwell-or-better don’t give up in this scenario; they fall back on the BTB. This means that on Broadwell or better, even retpoline code can end up using the attacker-prepared BTB. Intel says that a microcode update will address this. Alternatively, there are ways to “refill” the return buffer.

Branch predictors excel at making this kind of choice. Credit: Robert Couse-Baker

Generally, operating systems can either turn on IBRS and use IBPB when switching between virtual machines or recompile everything with retpoline (and refill the buffer when necessary and hope that Intel produces a suitable microcode update). Because Microsoft can’t depend on everything being rebuilt, Windows is using IBRS and IBPB when hardware permits; open source platforms are both investigating the use of retpoline and developing IBRS and IBPB solutions.

The broad pattern of performance overheads from these is similar to that for Meltdown: applications that don’t use the kernel often don’t see much difference, but applications that heavily depend on kernel functions show much higher overheads. Not only do they have to flush the TLB all the time, they’re now also flushing the BTB, too. This is a big deal: Intel estimates that branches are predicted with an accuracy in the high 90s percent. Wiping out the BTB all the time is going to cut that prediction rate drastically.

The costs of IBRS and IBPB can be substantial, however. The TechSpot benchmarks referenced previously show results both with a system firmware (and microcode) update and without. The firmware update enables the kernel’s IBRS and IBPB protection, allowing for a three-way comparison: Spectre + Meltdown protection, Meltdown protection only, and neither.

In regular desktop applications the overhead remained negligible, with games equally showing no meaningful difference in performance. But the storage benchmarks, which hammer the kernel with requests over and over, showed a substantial impact—sometimes as high as 40 percent.

The developers of DragonFly BSD are uncertain if the Spectre protection is even viable for their operating system. The performance decrease they’re seeing from IBRS and IBPB protection are around 24 percent on Skylake systems and as much as 53 percent on Haswell.

RedHat reports that Meltdown and Spectre together have an impact of between negligible and 19 percent, again depending on the I/O load. Database workloads such as the TPC-C industry standard database benchmark and pgbench see performance decreases of between 8 and 19 percent. CPU-intensive workloads such as SPECcpu see only 2-5 percent decreases.

A developing situation

It’s perhaps fortunate that the most readily exploited flaw—array bounds Spectre, attacked using browser-based JavaScript—appears to have low overhead mitigation. This is the attack vector that doesn’t require remote code execution or other flaws (because we all willingly download and run JavaScript within our browsers), so it’s particularly important that this one be protected. Most array bounds tests are safe, since attackers can’t control them, and judicious use of additional checks of the kind used by WebKit appears to add little overhead.

Beyond that, though, the way forward looks heavily dependent on both workload and current processor. Typical desktop users with Skylake, Kaby Lake, or Coffee Lake processors can freely enable both the Meltdown and Spectre defenses without worry. Virtualization hosts and cloud providers have little option but to enable the full range of protections, and they may not be able to get away with using retpoline alone, depending on their processors.

Users of older chips, and those with I/O-intensive workloads, may have to consider things more carefully. I’m sure that in due course we’ll see more numbers from older processors, but Microsoft’s warning of noticeable performance decreases paints a grim picture. Such users might end up picking and choosing—for example, opting into the Meltdown protection, but disabling the Spectre protection. As developers continue to wrestle with the problem, we’d expect the workarounds to become more efficient and the performance impact to decrease, but countering that, we may start to see workarounds for the workarounds, with crafty hackers defeating the protections.

One continued uncertainty at present is how many people will even be offered the Spectre protection. IBRS and IBPB require microcode updates. Microcode updates normally ship with system firmware updates and can also be performed by operating systems. Microsoft has microcode update drivers for Windows and could have rolled out the microcode update that way. But so far at least, the company hasn’t done this, instead deferring to OEMs to provide system firmware updates. Few OEMs provide any meaningful level of support after a year or two, meaning that many people who could potentially receive a microcode update probably won’t. This might result in better performance, by avoiding the Spectre protections, but isn’t a good step for system security.