The problem

I have dabbled with keeping journals in the past, but I've never managed to continue it for more than a year. The pattern is always the same: I struggle to write in the journal with any regularity, and sooner or later, I fall out of the journaling habit entirely. My problem is not that I run out of enthusiasm, but that I have trouble maintaining a reasonable scope for my entries.

Completionist impulses are my downfall. I'm prone to being too thorough – I want to record every event, document every detail, and capture every worthwhile thought from the day in service of compiling a meaningful chronicle of the life I've lived. But, as a logistical matter, this approach has proven untenable. Writing entries in that maximalist style takes hours. Eventually the task of recording a new day feels too burdensome to be enjoyable – to the point where I give up on writing new entries entirely.

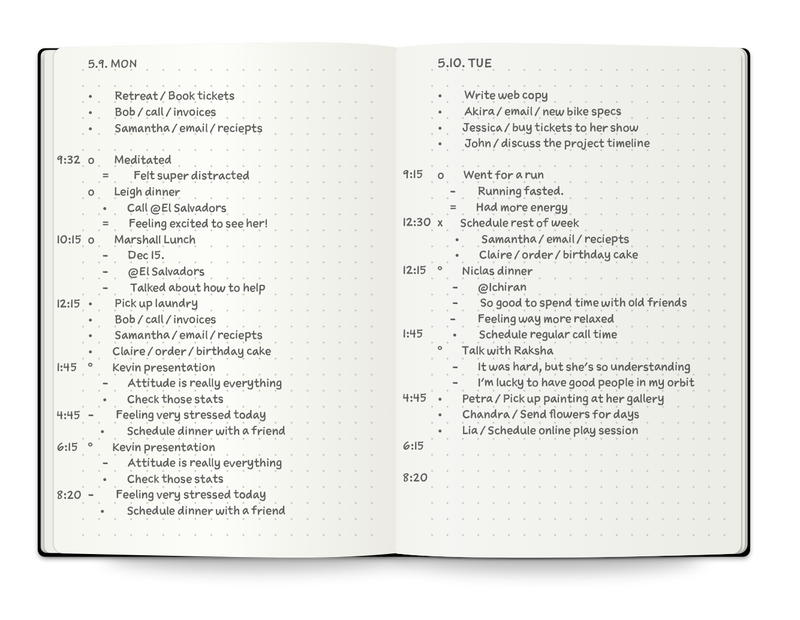

I've long understood that I would benefit from putting some kind of constraint in place to guard against my burnout-inducing tendencies. And for years, I searched for one. Yet the minimalist alternatives I came across were unsatisfactory – and unsatisfying. The bullet journal method, for example, never resonated with me. It felt too much like a daily planner, or a scattershot lumping of to-do lists and goals that, to me, seemed symptomatic of an irritating hustle-and-grind mindset. Maybe it could help people with organization, but it didn't look like it produced a journal worth revisiting – and what's the point of keeping a journal if you're not going to read through it eventually?1

What I needed was a method that would make journaling feasible while still producing a text I'd enjoy reading. In other words, I sought a journal format that would not only assist with remembrance, but would also make the act of remembering pleasurable. But what format could accomplish that?

The solution

I stumbled upon a solution in an unlikely place: Thousand Year Old Vampire, an excellent solo role-playing game by Tim Hutchings. In it, you chart the long life of a vampire in the first person, responding to random prompts as you follow the wax and wane of your vampire's fortunes. (You don't even need dice to play, since the rulebook includes random number tables you can rely on instead.) It's immensely enjoyable, and I've filled entire notebooks with my playthroughs.

What makes the game especially interesting, though, is how it treats memory.2 You must respond to prompts based on the resources your vampire has to hand and the history that it can remember. But its capacity for memories is finite, and as the centuries pass, you must choose which aspects of your vampire's life to retain or forget. This leads to poignant moments where, late in its life, your vampire can no longer recall the time when it was human, or finds that it has lost all trace of friends and family who mattered dearly to them in earlier times.

The game uses an ingenious mechanic for tracking all this. Your vampire holds five "Memories," which each have room for three "Experiences." The rulebook defines them as follows:

Memories and Experiences are important moments that have shaped your vampire, crystallized in writing. They make up the core of the vampire’s self—the things they know and care about. An Experience is a particular event; a Memory is an arc of Experiences that are tied together by subject or theme.

Experiences cover a particular event, but the amount of time represented by that event might vary dramatically. An Experience might describe a few seconds of impactful events, or it might cover two hundred years of lurking in an old castle.

[...]

An Experience should be a single evocative sentence. An Experience is the distillation of an event—a single sentence that combines what happened and why it matters to your vampire. A good format for an Experience is “[description of the event]; [how I feel or what I did about it].” If necessary, you can add an em dash at the end to include more information.3

As for how an experience might be written, the rulebook offers the following example:

Stalking the deserts over lonely years, I watch generations of Christian knights waste themselves on the swords of the Saracen; it’s a certainty that Charles is among them—I dream of his touch as I sleep beneath the burning sand.4

Thinking about the game recently, an idea occurred to me: Why not try keeping a real-life journal using the same strict format?

A daily journal entry could be as simple as "[description of occurrence] + [its upshot]," adapted as necessary.

I therefore decided I would approach journaling from this angle. I would aim to constrain each day's entry to one or two key things, and limit their expression to one or two sentences.

I allowed myself that latter tweak because the initial Thousand Year Old Vampire rule encourages improper semicolon usage and ugly run-on sentences, both of which strain language in hopes of cramming in as much as possible. The example sentence quoted above is rather clunky, after all – it clearly yearns to be two or three separate statements, and would be much more elegant if presented that way. I did not want such tortured, aesthetically unappealing text in my journal. I determined that capping entries at two sentences would leave space for well-composed writing without violating the spirit of concision behind the rule.

Benefits of the two-sentence approach

After conducting this experiment for a good while now, I'm pleased to have found it an unqualified success. Placing an ultra-strict ceiling on my journal entries has allowed me to maintain a continuous daily writing streak since starting. Not only has it been fun, it has brought about some other benefits, too. Here are some of the things I've found especially effective or rewarding about the two-sentence approach.

It requires almost no activation energy

Have you ever found that, the larger an undertaking, the less likely you are to start it? Maybe it's because you can't schedule the long block of uninterrupted time necessary for the task. Or it's because the prep work involved is an undertaking in and of itself. Or else the difficulty is that it takes too much effort to shift into the "flow" mindset you know you'll need.

I certainly have this problem – and it has halted my journaling efforts in the past.

Luckily, the two-sentence method sidesteps this issue by significantly reducing the activation energy necessary to sit down and write a journal entry. There's always time in the day to jot a sentence or two. And it's not much effort to write two sentences – it's the character equivalent of a text message or a microblog post!

Honestly, in my experience, the hardest part about keeping a two-sentence journal is remembering to do it.

It's reflective and meditative

The two-sentence limit forces you to think carefully about what you found most important, meaningful, or interesting about the day. I've found that fun in and of itself – it's like a puzzle, trying to home in on what I'd call the day's defining aspects.

But paring back the noise of the day's events doubles as a reflective exercise. Going over what happened during your day to pick out the part(s) that mattered most to you lets you process and appreciate all you've experienced in the past 24 hours. I have noticed that I'm more grateful for the things I choose to write about after I've sifted them from the rest of my day.

No day is wasted

With respect to the preceding point, to keep up with the journal is to engage in regular reflective/meditative exercise. It's good for you – you're always making the most of your day.

Yet there's also a sense of accomplishment that comes from making something. When you keep a regular journal, even your worst days add material to the book of your life. The two-sentence format makes it easy to take advantage of this principle, ensuring you can wring value out of every day.

This is both particularly apparent and particularly gratifying if you use a physical notebook for your journal. I fill out a page of the Moleskine I've dedicated to this project every 4-5 days, so I watch the literary output pile up at a steady rate. It feels great!

Days often turn into short stories

This is more of an emergent property that has nonetheless surprised me.

When I've looked back on the longer journal entries from my past efforts – or the entries in published journals by famous authors and thinkers – I've seldom found a narrative arc to them. It's not usually the intent behind such compositions, after all. They're typically collections of things that happened, and life rarely unfolds in accordance with the neat story structures of literature and film.

But an interesting thing happens when you present a reader with only two sentences: Somehow, a narrative logic appears.

I'm not entirely sure why this occurs, but I do have a working hypothesis. It's that noise dilutes story. When too many details pile up, or too many divergent threads appear in one place, it can be difficult to ascertain the overall point of the whole composition. This is basically what happens when somebody rambles in their writing or conversation – too much irrelevant material is brought in, such that the audience loses sight of the point.

Yet it's almost impossible to ramble when allotted only two sentences. This means that two-sentence journal entries tend to cut right to the point, with every inclusion being relevant. Thanks to that concise presentation, every entry seems to have a visible arc. And as a result, narratives often materialize from the short texts each enty comprises. (I've included some examples from my own journal toward the end of this post to help illustrate what I mean.)

It demonstrates the aesthetic merit of the two-sentence paragraph

Perhaps the curriculum has changed since I was an elementary schooler in the United States, but I remember having it drilled into me that a paragraph was always a minimum of three sentences. Those lessons instilled in me a pathological aversion to anything less. I carried that three-sentence prejudice for years, even shying away from the one-sentence paragraphs that have proven rhetorically effective in many works of prose. If you were schooled similarly to me, you might have the same hang-ups.

Yet my experiments in constrained journal formatting have taught me that the two-sentence paragraph is a remarkably powerful construction.5

Like Kuleshov's and Eisenstein's theories of cinematic montage – which observe that the juxtaposition of two images creates an impression or idea distinct from what either one produces in isolation – placing two sentences alone with one another in a single paragraph leads to intriguing effects.

Sometimes the two sentences assume a causal relation, with the first triggering the second. On other occasions, they invite a comparison, with each one throwing the other into relief. They can read like a reversal, where the second undermines the first, or a redirection wherein the second suddenly makes clear an unexpected dramatic trajectory. There are even times where you end up with an ambiguous but palpable connective logic, like what the kireji in a haiku provides, and contemplating the nature or meaning of that connection gives the paragraph its force.

The two-sentence journal provides ample space to explore these effects – and to observe their potency firsthand.

Sample entries

To give you a sense of how fun and evocative the two-sentence journal format can be, here are some entries from my own journal this past week.6 I'm amazed by the inner lives and wider worlds you can conjure despite (or because of) such tight constraints.

Limped my way to the work day's end, exposing how badly I need the week-long vacation I now begin. A surprise downpour cut short the evening walk with my wife and dog, but, drenched to the skin though we were, we laughed the entire trek home.

Torrential rains swept through our part of town all morning, washing away the road outside our neighborhood's entrance. Tomorrow the nearby construction sites will resume felling every tree in reach and introducing impermeable surfaces where grass once grew.

I spent this last day of my vacation polishing the living room table – a piece older than I am that once belonged to my parents. It absorbed the applied mineral oil like it thirsted, and as I ran the cloth over its sturdy surfaces, I felt as though it were a living being whose care I had neglected.

Parting thoughts

So there you have it – the complete rundown of the two-sentence journal method.

If my approach sounds appealing or interesting to you, I encourage you to try it for yourself. I have greatly enjoyed keeping a two-sentence journal, and I imagine you will, too.

And if you come up with any entries you're willing to share, please consider sending them my way! I'd be curious to see what people do with this journal format and where they take it.

Notes

This being said, if you like bullet journaling, more power to you! It's not my method, but that doesn't mean it can't be yours.↩

The physical rulebook also confers considerable interest – it's an art object unto itself, presented like an old library book stuffed full of scrapbook-like images and unusual inserts. It's great fun to explore in and of itself.↩

Hutchings, Tim. Thousand Year Old Vampire. Petit Guignol, 2020. 4.↩

Ibid., 6.↩

Admittedly, I should have recognized this sooner. The Nobel laureate Yasunari Kawabata understood it well, demonstrating in novels like Snow Country that the two-sentence paragraph is fertile artistic ground. I didn't notice his use of the technique my first time reading him, much less what he achieves with it.↩

I typically append the date, day of week, and place of writing to the start of each entry, too. (For instance, 10 August 2025 / Sunday / Boston, MA: [ENTRY TEXT].) I recommend including whatever date/time/location information suits your tastes.↩