Airbyte’s rapid growth meant we recently had to take a closer look at our infrastructure. This led us to lean harder on the control-plane/data-plane split we introduced and rethink load balancing for more scalability. Leaning harder on the control-plane / data-plane split meant two things. First, we like how it helped us scale up. Second, we should update our internal APIs to better leverage this split.

In this article, I will introduce the Workload API and how this abstraction is the next step in improving the scalability and resilience of Airbyte 1.0. While this workload concept is an Airbyte internal detail, we thought it was still worth documenting as it also gives insights on some Airbyte’s reliability and scalability design.

For context, Workload API has been in the works for the past year. This has been Airbyte Cloud’s default implementation since the beginning of the year. We strongly believe the reliability and operational improvements of Workloads benefits all our users and are very excited to release Workloads over the next few weeks. Stay tuned for more news!

The Airbyte Worker

A recurring question is what is the airbyte-worker and why does it need so much memory. The airbyte-worker is the core of our scheduling, handles our orchestration as well as the nitty-gritty details of interacting with Kubernetes to start our job pods. In short, a lot of concerns of different nature and level are packed in this mighty application.

Scheduling and orchestration are about higher order operations. For example, when should the next sync run, if the previous run failed, should we retry now or defer to the next scheduled run? What are the operations that need to be performed as part of a sync? Should we run check or discover? As we introduced in a previous article, Airbyte uses Temporal for orchestration, and the airbyte-worker is the host application for those activities.

The worker also manages job processes or pods. While some of this made sense when running Airbyte in Docker, supporting Kubernetes deployments added new considerations - how do we start pods, check their lifecycle and how some events impact the rest of our workflow. Expanding further into multiple clusters opened up a new line of questions:

- Do we want to run scheduling, sync orchestration from the data-plane?

- What belongs in the control-plane?

Our answer: separate the scheduling and orchestration from core data movement processes, a.k.a Workloads.

Workloads

We’re defining workloads as the tasks most directly related to data movement. I say related to data movement because not all tasks move data. The Airbyte protocol has a few commands. Read and Write are really the core of data movement, while Check and Discover are more configuration related. Workloads allow us to abstractly reason about these commands. Any connector operation can be described as a Workload.

Within the Airbyte platform, a Workload is the backbone of data movement. Looking back at our control-plane / data-plane split, a workload naturally fits within a data-plane as the muscle of data movement. The control-plane in return needs to be able to create workloads and be aware of their lifecycle; however, it shouldn’t interact directly with the workload itself in order to maintain proper separation of concerns.

The Workload API

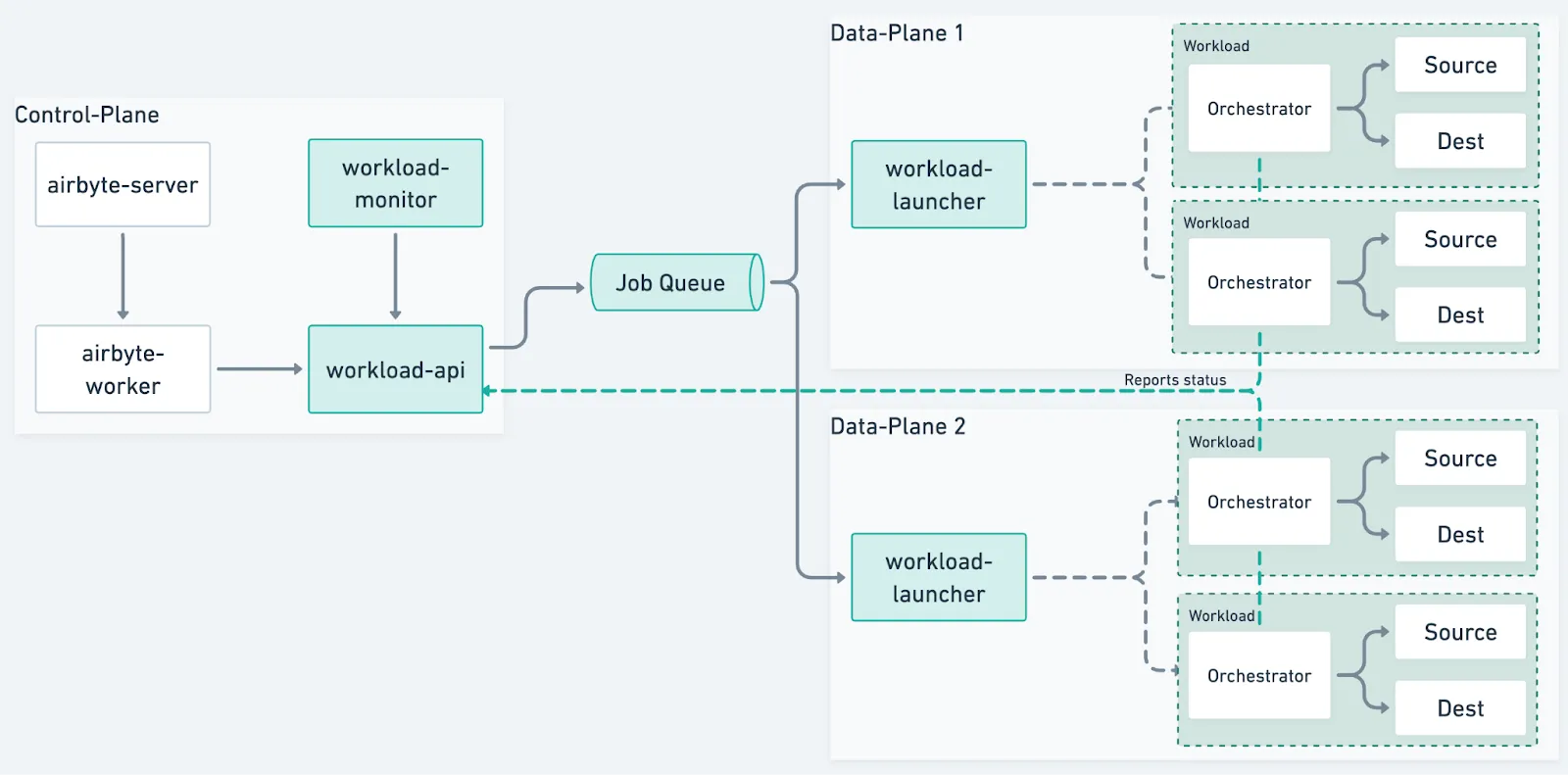

The Workload API is the abstraction separating the control-plane from the data-plane.

All the control-plane needs to support is the creation of workloads as well as the ability to track the outcome of a workload. This effectively severs the coupling between the airbyte-worker and the job pods. This allows scheduling and the orchestration to be decoupled from the implementation of the workload as long as the correct interface is implemented.

In practice, this API is implemented through the workload-api-server which will be responsible for being the source truth of our workloads. We decided to treat it as a standalone server for performance reasons. The workload-api-server plays an important role in how we validate connectivity between different zones. It made sense to keep it separate for the time being for an improved observability and configurability. So far we have validated that this new server scales well and handles thousands of requests per second.

In the previous post about load balancing, I mentioned inversion of control helped us simplify the scope of the problem at hand, Workloads are an example. In our former implementation, the orchestration was checking on the pods and the pods could be updating job status. In order to know whether a job was running, we had processes querying each data-plane and reconciling with our job states which could temporarily diverge depending on the source. Moving forward, the Workload API becomes the source of truth of whether a workload is and should be running.

With this in mind, workload creation requests are submitted to this API who will be responsible for pushing the actual creation into a queue that will eventually lead to a workload being created on a data-plane. The same API also exposes endpoints to check on a workload’s status, and cancel it. It also exposes endpoints for workloads to update their current state. We have already seen this benefit from an operational point of view: operators can now interact with this API to query or signal a workload without having to dive into the internals of the scheduling system which was not possible.

The Workload Launcher connects data-planes to the control-plane

The workload-launcher becomes the key component of a data-plane. It is responsible for consuming jobs from the queue and ensuring that sync pods are started.

The launcher is the entrypoint to a data-plane and key in our load-balancing strategy. Load on a single Kubernetes cluster is a top of mind concern.Specifically, making sure a given Kubernetes cluster has enough resources to host the pending pods. This problem is described with more details in this post that goes into more details of our load balancing strategy. The gist of it is to have data-planes competing for jobs and back-off when out of capacity rather than having a top-down assignment of jobs. The launcher is the component that is consuming from the job queue.

Load balancing across data-planes

The load balancing strategy is to let different instances compete for pending workloads by taking them out of the queue. This avoids top-down assignment and helps avoid some operational overhead such as requeuing when having to deal with pending workloads assigned to a specific cluster when that cluster becomes unavailable. The system self-heals as long as more data planes are added, an operation made simpler by the Workload API.

Once a workload is taken by a launcher, it will effectively claim it from the Workload API. From that point, a workload has been assigned to a data-plane and will not be re-assigned. This improves traceability and debugging if needed as we can query the workload API to know where a workload was processed.

Mitigating deadlocks with back-pressure

As the consumer of the queue, this puts the launcher in a good position to apply back pressure to avoid overloading a data-plane.

An initial idea was to have a launcher be aware of the available resources within the cluster and decide whether to consume from the queue accordingly. This remains generally a hard task due to auto-scaling and cloud provider compute capacity. Even if the cluster is configured to scale up to a certain number of nodes. There’s always a chance it would not be able to. Further, introspecting a cluster’s resources breaks Kubernetes abstraction and is not straightforward.

Let’s take a closer look at an overloaded cluster situation. The most visible aspect from a user point of view other than potential delays is failure rate. One of the downsides of churning through workloads when overloaded is that we’re expanding the span of job failures. In an overloaded situation, failing a workload to try the next one still has a decent chance of having this next one fail for similar reasons. With this in mind, it makes sense to actually hang on to current in flight workloads until resources free up.

This explains our current approach of avoiding the available resource capacity problem by focusing on what we can control: our workload launch throughput or the current number of workloads being started at the same time. By controlling this throughput, we can make sure to apply enough pressure to a Kubernetes cluster to ensure it scales up as much as possible. When at capacity, we simply stop consuming new jobs from the queue.

In the meantime, pending jobs remain in the queue, free for any available data-plane.As long as another cluster has capacity, these jobs still get processed in a timely fashion. At a global scale, this is a better failure pattern. Only pending jobs in the overloaded cluster may fail if the cluster never recovers. However, in that situation, they would have failed anyway.

In summary, our strategy is to fix a number of consumers of the queue for a given data-plane. Each consumer is responsible for processing a workload and will block until the workload is either launched or failed to launch. This mitigates the deadlock situation by controlling the amount of competing pods. In the event where only one of the clusters is under pressure, the others will be able to keep on processing pending workloads effectively removing the need for requeuing.

Thoughts on retry strategies

Another reason to avoid requeuing is to simplify the handling of retries. At a high level it makes sense to have some retries, especially in the case of transient infrastructure related failures. However, there are cases where retrying does not always make sense. For example, we may want to retry immediately when a connection is dropped, however, invalid credentials might be worth waiting until the configuration has been updated or at the next scheduled run.

While intuitively it feels right to retry infrastructure related errors at the launcher level, complex retry logic makes the overall flow harder to reason about. In order to keep things simple, we decided that the launcher wouldn’t retry internally and let the top level workflow decide on the better course of action.

What we define as retry in this specific context is the action of requeuing a workload to have it potentially processed by another data-plane. This breaks the simplicity we get from having workloads claimed only once. We do want to be resilient to transient errors such as flakiness that may occur around API calls or delays on the Kubernetes cluster. This class of errors are handled by the launcher as they are mainly very local problems.

However, once we reach an error state, the decision to retry will always be taken from the top level to make it easier to reason about the different types of failures and define rules that could take both infrastructure and business logic into account.

Workloads are responsible for reporting their status

A sync is composed of three pods – a source connector, a destination connector and an orchestrator. The role of the orchestrator is to channel data between source and destination and perform administrative functions such as data completeness validation and checkpointing.

Our new design means a workload is now responsible for checking in and reporting back its status. This is no longer handled by the airbyte-worker, and is now done by the orchestrator pod. A direct benefit from this is a huge load reduction on the Kubernetes API as this removes the need of excessive polling or watchers to track unexpected pod termination. Less chatty Kubernetes networks generally means a more stable execution environment.

Heartbeats for bidirectional communication

A workload is now expected to heartbeat at a given cadence. This is how the control plane knows that a given workload is still healthy. This used to be done from the airbyte-worker which wasn’t ideal in terms of isolation because the worker needed to be aware of implementation details such as how to find pods in Kubernetes to check their status.

Since direct communication from the control-plane to a workload has been consciously severed, we have overloaded this same API used for heartbeating to also give workload updates about expectations from the control-plane. For example, if a workload has been canceled, the workload will receive that information from the server and effectively abort processing.

Handling network partitioning

It is safe to assume infrastructure eventually fails. A common concern is networking, especially across zones. There will come a time where a data-plane cannot reach a given control-plane.

With our current design, when that happens, the control-plane will eventually consider all the workloads as unhealthy and fail them. This can be a problem considering that in some instances the workloads may in practice still be healthy.

There are however other factors at play. If a data-plane cannot reach the control-plane, we’re facing other issues. Some tracking information may end up out of sync, but most of all, syncs cannot be checkpointed, which means that we will be duplicating work if the sync terminated during the network split.

Not knowing the status of a workload comes with risks as well. Let’s assume we let the workload run indefinitely, what happens on the next schedule? If workloads continue to completion regardless, we may schedule duplicate sync which could introduce data inconsistency. This level of uncertainty implies a risk whenever it comes to retrying a workload from a heartbeat failure.

Turns out having workloads self-terminate when unable to heartbeat after some time also yields a more practicable outcome from the control-plane. We can reasonably expect workload to no longer be running after a known amount of time, which means that we can start recovering by rescheduling workloads on other data-planes unaffected by the network failure.

The Workload Monitor

Last but not least, the workload-monitor ties our entire design together. I described some time based actions such as action upon missing heartbeats. The workload-monitor is responsible for failing a workload due to a failure to report back within an expected period of time. The monitor is a lightweight control plane application. It is a set of cron tasks running within the airbyte-cron to avoid expanding our footprint more than needed.

Summarizing

Workloads are the next iteration of the Airbyte platform for reliability and scalability. This started from a need to scale up Airbyte Cloud and resulted in significant stability improvements that benefit all users.

Workloads unlock the ability to scale across the boundaries of a single cluster while reducing the fallout of various disaster situations. The most notable one being when running Airbyte in a resource constrained environment. With this redesign, what used to be cascading failures and deadlocks is now a back-pressured self-healing system with greatly simplified operational protocols and reduced running costs.

What other great readings

This article is part of a series of articles we wrote around all the reliability features we released for Airbyte to reach the 1.0 status. Here are some other articles about those reliability features:

- Handling large records

- Checkpointing to ensure uninterrupted data syncs

- Load balancing Airbyte workloads across multiple Kubernetes clusters

- Resumable full refresh, as a way to build resilient systems for syncing data

- Refreshes to reimport historical data with zero downtime

- Notifications and Webhooks to enable set & forget

- Supporting very large CDC syncs

- Monitoring sync progress and solving OOM failures

- Automatic detection of dropped records

Don't hesitate to check on what was included in Airbyte 1.0's release!