Benches in parks, train stations, bus shelters and other public places are meant to offer seating, but only for a limited duration. Many elements of such seats are subtly or overtly restrictive. Arm rests, for instance, indeed provide spaces to rest arms, but they also prevent people from lying down or sitting in anything but a prescribed position. This type of design strategy is sometimes classified as “hostile architecture,” or simply: “unpleasant design.”

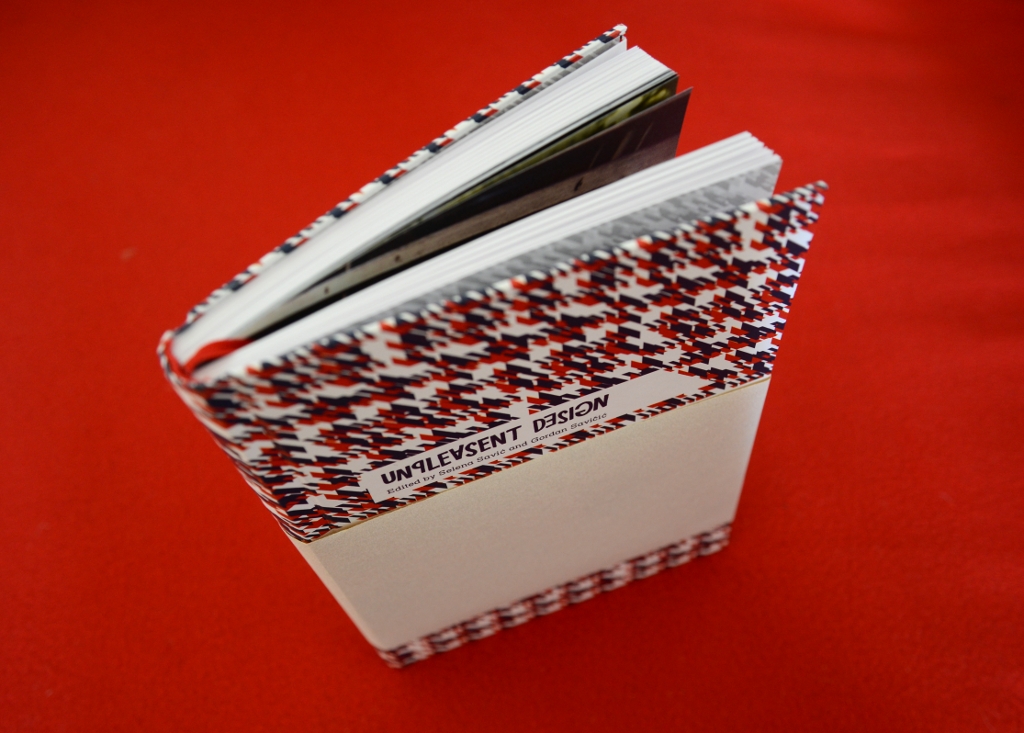

Gordan Savičić and Selena Savić, co-editors of the book Unpleasant Design, are quick to point out that unpleasant designs are not failed designs, but rather successful ones in the sense that they deter certain activities by design. A bench which fails to be comfortable and flexible, for example, can still be a successful design … if the designer intends for it to be an uncomfortable place to spend long periods of time.

Unpleasant designs take many shapes, but they share a common goal of exerting some kind of social control in public or in publicly-accessible private spaces. They are intended to target, frustrate and deter people, particularly those who fall within unwanted demographics.

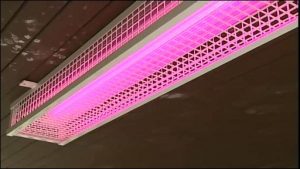

A number of such strategies are aimed loitering teens, and many of these are less physical or obvious than an uncomfortable bench. Some businesses play classical music as a deterrent, on the theory that kids don’t want to hang out or talk over it. Other sound-based strategies include the use of high-frequency sonic buzz generators meant to be audible only to young people. Housing estates in the UK have also put up pink lighting, aimed to highlight teenage blemishes. In many cases, there is little data to show how well these more unconventional strategies actually work.

At the other end of the spectrum, blue lighting has been used in public restrooms to deter intravenous drug users; the color makes it harder for people to locate their veins. Public street crime declined in Glasgow, Scotland following the installation of blue street lights, but it’s difficult to attribute this effect to the new lighting. Blue may have calming effects or may simply (in contrast to yellow) create an unusual atmosphere in which people are uncomfortable acting out. Though questions remain about causality versus correlation in this case, Tokyo, Japan has since piloted a similar blue-light program, hoping to reduce suicides in subway stations.

The use of lighting as a means of public control may be much older than these color-specific interventions. According to Selena Savić, when Austria-Hungary annexed Bosnia the government installed unpleasantly bright street lamps in Višegrad. Their goal was to deter nighttime gatherings that could lead to resistance or rebellion. The locals, displeased with these lights, would break the lamps at night, and the government would reinstall them the next day. A similar phenomenon (of street lights as social control) dates back even further in Paris, France.

Today, we have since become so habituated to public lighting that our primary association with street lights is that they deter criminal activity and make us feel safe. Except for those who lament the lack of stars in the night sky or live in apartments next to a too-bright bulb, one might never consider the possibility that street lighting might be unpleasant. This is part of the point of the Unpleasant Design project and book: to bring these rarely-noticed phenomenon to light, so to speak.

While some examples are more invisible, or at least intangible, other hostile architectural interventions are more physical and overt. Concrete or metal spikes are used to keep people from urinating in dark city corners, while others are aimed at stopping people from sleeping on the streets.

One major problem of the spikes (and all the unpleasant designs that curb undesired behavior) is that, unlike interactions with security guards or police officers, these physical features are non-negotiable. Their permanence is definitive and uncompromising, baked into the built environment in a way that is hard to argue against or reverse.

Spikes aside, street furniture is one of the most common subjects of unpleasant design critiques. The limitations built into urban objects restrict activities, denying a potentially complex range of uses and interactions. Beyond dividers and armrests, some benches are mounted so high that a sitter’s feet will not reach the ground, making them uncomfortable after a short period. In other cases, shared seats are barely benches at all, just slim slats to stand and rest against.

Of all these bench designs, there is one masterpiece in particular that stands out from the crowd. The Camden Bench is a highly refined work of unpleasant design, impervious to essentially anything but sitting.

Designed by Factory Furniture, the Camden Bench is a strange, angular, sculpted, solid lump of concrete with rounded edges and slopes in unexpected places. Critic Frank Swain calls it the “perfect anti-object.”

The Camden Bench is virtually impossible to sleep on. It is anti-dealer and anti-litter because it features no slots or crevices in which to stash drugs or into which trash could slip. It is anti-theft because the recesses near the ground allow people to store bags behind their legs and away from would be criminals. It is anti-skateboard because the edges on the bench fluctuate in height to make grinding difficult. It is anti-graffiti because it has a special coating to repel paint. It can also be lifted into place as a roadblock for crowd control.

Most of these goals seem noble, but the overall effect is somewhat demoralizing, and follows a potentially dangerous logic with respect to designing for public spaces. When design solutions address the symptoms of a problem (like sleeping outside in public) rather than the cause of the problem (like the myriad societal shortcomings that lead to homelessness), that problem is simply pushed down the street.

Spikes beget spikes, and targeted individuals are simply moved around … in much the same way that pigeon deterrents shuffle birds from block to block without reducing their overall numbers in a city.

Meanwhile, some guerrilla efforts have been made to fight back against unpleasant designs. Artist Sarah Ross, for instance, created a set of “archisuits” designed to work in and around specific deterrents. In one such suit, pads with gaps let the wearer sleep on segmented benches.

Softwalks has developed a series of attachable city seats and tables that clamp onto scaffolding and other urban posts or poles. Their modular on-demand street furniture is in part practical but also makes a statement about hostility and voids and built environments.

Whether handed down by the establishment or created in response to official interventions, there is always an aspect of coercion to design. Usability design, for instance, is used to get people to buy things and use their smartphones in certain ways, often without the user even being aware of it. Fundamentally, works of unpleasant design, hostile architecture and street furniture in general are no different.

The reason we need a critical theory of unpleasant design is so we can recognize the coercion that is taking place in our public spaces. We need to know when we are replacing human interaction, nuance and empathy with hard, physical and non-negotiable solutions.

Whether you think a certain form of design is exclusionary but serves a greater good, or believe it is just hostile and offensive, it is important to be aware of the decisions that are being made for you. Designs that are unpleasant to some are put into place to make things more pleasant for others, and that latter category might just include you.