The PLUM reading group recently discussed the paper, DR CHECKER: A Soundy Analysis for Linux Kernel Drivers, which appeared at USENIX Securty’17. This paper presents an automatic program analysis (a static analysis) for Linux device drivers that aims to discover instances of a class of security-relevant bugs. The paper is insistent that a big reason for DR CHECKER’s success (it finds a number of new bugs, several which have been acknowledged to be true vulnerabilities) is that the analysis is soundy, as opposed to sound. Many of the reading group students wondered: What do these terms mean, and why might soundiness be better than soundness?

To answer this question, we need to step back and talk about various other terms also used to describe a static analysis, such as completeness, precision, recall, and more. These terms are not always used in a consistent way, and they can be confusing. The value of an analysis being sound, or complete, or soundy, is also debatable. This post presents my understanding of the definitions of these terms, and considers how they may (or may not) be useful for characterizing a static analysis. One interesting conclusion to draw from understanding the terms is that we need good benchmark suites for evaluating static analysis; my impression is that, as of now, there are few good options.

Soundness in Static Analysis

The term “soundness” comes from formal, mathematical logic. In that setting, there is a proof system and a model. The proof system is a set of rules with which one can prove properties (aka statements) about the model, which is some kind of mathematical structure, such as sets over some domain. A proof system L is sound if statements it can prove are indeed true in the model. L is complete if it can prove any true statement about the model. Most interesting proof systems cannot be both sound and complete: Either there will be some true statements that L cannot prove, or else L may “prove” some false statements along with all the true ones.

We can view a static analysis as a proof system for establishing certain properties hold for all of a program’s executions; the program (i.e., its possible executions) plays the role of the model. For example, the static analyzer Astrée aims to prove the property R, that no program execution will exhibit run-time errors due to division by zero, out-of-bounds array index, or null-pointer dereference (among others). Astrée should be considered sound (for R) if, when it says the property R holds for some program, then indeed no execution of the program exhibits a run-time error. It would be unsound if the tool can claim the property holds when it doesn’t; i.e., when at least one execution is erroneous. My understanding is that Astrée is not sound unless programs adhere to certain assumptions; more on this below.

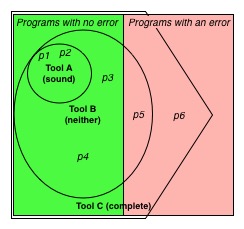

The figure to the right shows the situation visually. The left half of the square represents all programs for which property R holds, i.e., they never exhibit a run-time error. The right half represents programs for which R does not hold, i.e., some executions of those programs exhibit an error. The upper left circle represents the programs that an analyzer (tool) A says satisfy R (which include programs p1 and p2); all programs not in the circle (including p3-p6) are not proven by A. Since the circle resides entirely in the left half of the square, A is sound: it never says a program with an error doesn’t have one.

False Alarms and Completeness

A static analysis generally says a program P enjoys a property like R by emitting no alarms when analyzing P. For our example, tool A therefore emits no alarm for those programs (like p1 and p2) in its circle, and emits some alarm for all programs outside its circle. For the programs in the left half of the figure that are not in A‘s circle (including p3 and p4) these are false alarms since they exhibit no run-time error but A says they do.

False alarms are a practical reality, and a source of frustration for tool users. Most tool designers attempt to reduce false alarms by making their tools (somewhat) unsound. In our visualization, tool B is unsound: part of its circle includes programs (like p5) that are in the right half of the square.

At the extreme, a tool could issue an alarm only if it is entirely sure the alarm is true. One example of such a tool is a symbolic executor like KLEE: Each error it finds comes with an input that demonstrates a violation of the desired property. In the literature, such tools—whose alarms are never false—are sometimes called complete. Relating back to proof theory, a tool that emits no alarms is claiming that the desired property holds of the target program. As such, a complete tool must not issue an alarm for any valid program, i.e., it must have no false alarms.

Returning to our visualization, we can see that tool C is complete: Its pentagon shape completely contains the left half of the square, but some of the right half as well. This means it will prove property R for all correct programs but will also “prove” it (by emitting no alarm) for some programs that will exhibit a run-time error.

Soundiness

A problem with the terms sound and complete is that they do not mean much on their own. A tool that raises the alarm for every program is trivially sound. A tool that accepts every program (by emitting no alarms) is trivially complete. Ideally, a tool should strive to achieve both soundness and completeness, even though doing so perfectly is generally impossible. How close does a tool get? The binary soundness/completeness properties don’t tell us.

One approach to this problem is embodied in a proposal for an alternative property called soundiness. A soundy tool is one that does not correctly analyze certain programming patterns or language features, but for programs that do not use these features the tools’ pronouncements are sound (and exhibit few false alarms). As an example, many Java analysis tools are soundy by choosing to ignore uses of reflection, whose correct handling could result in many false alarms or performance problems.

This idea of soundiness is appealing because it identifies tools that aim to be sound, rather than branding them as unsound alongside many far less sophisticated tools. But some have criticized the idea of soundiness for the reason that it has no inherent meaning. It basically means “sound up to certain assumptions.” But different tools will make different assumptions. Thus the results of two soundy tools are (likely) incomparable. On the other hand, we can usefully compare the effectiveness of two sound tools.

Rather than (only) declare a tool to be soundy, we should declare it sound up to certain assumptions, and list what those assumptions are. For example, my understanding is that Astrée is sound under various assumptions, e.g., as long as the target program does not use dynamic memory allocation. [Edit: There are other assumptions too, including one involving post-error execution. See Xavier Rival’s comment below.]

Precision and Recall

Proving soundness up to assumptions, rather than soundness in an absolute sense, still does not tell the whole story. We need some way of reasoning about the utility of a tool. It should prove most good programs but few bad ones, and issue only a modicum of false alarms. A quantitative way of reporting a tool’s utility is via precision and recall. The former is a measure that indicates how often that claims made by a tool are correct, while the latter measures what fraction of possibly-correct claims are made.

Here are the terms’ definitions. Suppose we have N programs and a static analysis such that

- X of N programs exhibit a property of interest (e.g., R, no run-time errors)

- N-X of them do not

- T ≤ X of the property-exhibiting programs are proved by the static analysis; i.e., for these programs it correctly emits no alarms

- F ≤ N-X of the property-violating programs are incorrectly proved by the analysis; i.e., for these programs it is incorrectly silent

Then, the static analysis’s precision = T/(T+F) and its recall = T/X.

A sound analysis will have perfect precision (of 1) since for such an analysis we always have F=0. A complete analysis has perfect recall, since T=X. A practical analysis falls somewhere in between; the ideal is to have both precision and recall scores close to 1.

Recall our visualization. We can compute precision and recall for the three tools on programs p1-p6. For these, N=6 and X=4. For tool A, parameter T=2 (i.e., programs p1 and p2) and parameter F=0, yielding precision=1 (i.e., 2/2) and recall=1/2 (i.e., 2/4). For tool B, parameter T=4 (i.e., programs p1-p4) and F=1 (i.e., program p5), so it has precision=4/5 and recall=1. Finally, tool C has parameter T=4 and F=2 (i.e., programs p5 and p6), so it has precision=2/3 and recall=1.

Limitations of Precision and Recall

While precision and recall fill in the practical gap between soundness and completeness, they have their own problems. One problem is that these measures are inherently empirical, not conceptual. At best, we can compute precision and recall for some programs, i.e., those in a benchmark suite (like p1-p6 in our visualization), and hope that these measures generalize to all programs. Another problem is that it may be difficult to know when the considered programs do or do not exhibit a property of interest; i.e., we may lack ground truth.

Another problem is that precision and recall are defined for whole programs. But practical programs are sufficiently large and complicated that even well engineered tools will falsely classify most of them by emitting a few alarms. As such, rather than focus on whole programs, we could attempt to focus on program bugs. For example, for a tool that aims to prove array indexes are in bounds, we can count the number of array index expressions in a program (N), the number of these that are properly in bounds (X), and the number the tool accepts correctly by emitting no alarm (T) and those it accepts incorrectly by failing to emit an alarm (F). By this accounting, Astrée would stack up very well: It emitted only three false alarms in a 125,000 line program (which presumably has many occurrences of array index, pointer dereference, etc.).

This definition still presents the problem that we need to know ground truth (i.e., X) which can be very difficult for certain sorts of bugs (e.g., data races). It may also be difficult to come up with a way of counting potential bugs. For example, for data races, we must consider (all) feasible thread/program point combinations involving a read and a write. The problem of counting bugs raises a philosophical question of what a single bug even is—how do you separate one bug from another? Defining precision/recall for whole programs side-steps the need to count.

Conclusion

Soundness and completeness define the boundaries of a static analysis’s effectiveness. A perfect tool would achieve both. But perfection is generally impossible, and satisfying just soundness or completeness alone says little that is practical. Precision and recall provide a quantitative measure, but these are computed relative to a particular benchmark suite, and only if ground truth is known. In many cases, the generalizability of a benchmark suite is unproven, and ground truth is uncertain.

As such, it seems that perhaps the most useful approach for practical evaluation of static analysis is to make universal statements—such as soundness or completeness (up to assumptions) which apply to all programs—and empirical statements, which apply to some programs, perhaps with uncertainty. Both kinds of statements give evidence of utility and generalizability.

To do this well, we need benchmark suites for which we have independent evidence of generalizability and (at least some degree of) ground truth. My impression is that for static analysis problems there is really no good choice. I would suggest that this is a pressing problem worth further study!

Thanks to Thomas Gilray, David Darais, Niki Vazou, and Jeff Foster for comments on earlier versions of this post.