In

1968, Intel Corporation was founded to exploit the semiconductor memory

market, which uniquely fulfilled these criteria. Early semiconductor RAMs,

ROMs, and shift registers were welcomed wherever small memories were needed,

especially in calculators and CRT terminals, In 1969, Intel engineers began

to study ways of integrating and partitioning the control logic functions of

these systems into LSI chips. At this time other companies (notably Texas

Instruments) were exploring ways to reduce the design time to develop custom

integrated circuits usable in a customer's application. Computer-aided

design of custom ICs was a hot issue then. Custom ICs are making a comeback

today, this time in high-volume applications which typify the low end of the

microprocessor market. An alternate approach was to think of a customer's

application as a computer system requiring a control program, I/O monitoring,

and arithmetic routines, rather than as a collection of special-purpose

logic chips. Focusing on its strength in memory, Intel partitioned systems

into RAM, ROM, and a single controller chip, the central processor unit

(CPU).

Intel

embarked on the design of two customer-sponsored microprocessors, the 4004

for a calculator (Intel receives a request from Japan's ETI/Busicom to

develop integrated circuits for a line of calculators - the design becomes

the 4004 microprocessor) and the 8008 for a CRT terminal (developed for

Computer Terminal Corporation - later called DataPoint).

Intel

embarked on the design of two customer-sponsored microprocessors, the 4004

for a calculator (Intel receives a request from Japan's ETI/Busicom to

develop integrated circuits for a line of calculators - the design becomes

the 4004 microprocessor) and the 8008 for a CRT terminal (developed for

Computer Terminal Corporation - later called DataPoint).

The 4004, in

particular, replaced what would otherwise have been six customized chips,

usable by only one customer. Because the first microcomputer applications

were known, tangible, and easy to understand, instruction sets and

architectures were defined in a matter of weeks. Since they were

programmable computers, their uses could be extended indefinitely.

The 4004, in

particular, replaced what would otherwise have been six customized chips,

usable by only one customer. Because the first microcomputer applications

were known, tangible, and easy to understand, instruction sets and

architectures were defined in a matter of weeks. Since they were

programmable computers, their uses could be extended indefinitely.

Both

of these first microprocessors were complete CPUs-on-a-chip and had similar

characteristics. But because the 4004 was designed for serial BCD arithmetic

while the 8008 was made for 8-bit character handling, their instruction sets

were quite different.

� Texas Instruments: They invented the Microcontroller

U.S.

Patent Office Rules TI Engineer Invented Computer-On-A-Chip

The

U.S. Patent and Trademark Office has affirmed that Texas Instruments

engineer Gary W. Boone is the inventor of the single-chip microcontroller, a

device that revolutionized electronics by putting all the functions of a

computer on one piece of silicon.

The

Patent Office ruling, which was just released, is the outcome of a five-year

proceeding to determine whether a highly publicized patent awarded in the

summer of 1990 to Gilbert P. Hyatt, covered an invention made first by Mr.

Boone at TI. The patent office proceeding, known as an interference, focused

on who was first to invent the single-chip microcontroller.

"This

ruling rightfully establishes Gary Boone and TI as the inventor of the

single-chip microcontroller, settling the broad speculation that followed

after Mr. Hyatt received a patent. Gilbert Hyatt has absolutely no claim on

the invention," said Richard Donaldson, senior vice president and

general patent counsel for TI.

The

Patent Office also granted TI's request for a statutory invention

registration (SIR), which will officially recognize Gary Boone and TI as the

inventor of the single-chip microcontroller. TI

holds

several patents covering the commercial implementation of

the

computer-on-a-chip, based on work done by Mr. Boone and other TI inventors,

resulting from TI's effort in the late 1960s and 1970s on TI's

TMS100 and

TMS1000 microcontroller families.

"TI

has nothing to gain financially now from receiving another patent on Boone's

basic invention of the computer-on-a-chip," explained Mr. Donaldson.

"What is important is the Patent Office's confirmation that Gary Boone

and TI were first to invent the computer-on-a-chip."

A

notice will be attached to Mr. Hyatt's U.S. Patent No. 4,942,516 (Single

chip integrated circuit computer architecture) explaining that his claims

for invention of the single-chip microcontroller have been canceled.

This

ruling will have no effect on TI royalties or its intellectual property

licensing program.

The

computer-on-a-chip, also known as the single-chip

microcontroller,

is a tiny sliver of silicon containing all the essential parts of a computer.

Single-chip microcontrollers are widely used in computer keyboards,

automatic ignition systems, television and videocassette recorder controls,

and other household and industrial applications. Unlike microprocessor chips,

single-chip microcontrollers contain on-chip permanent computer programs

that direct the chip to perform predetermined functions. Microprocessor

chips rely on external program storage devices, such as memory chips or disk

drives.

Boone

invented the computer-on-a-chip while working on the TMS100 microcontroller

chip, which TI introduced commercially in late 1971 (read the original press

release here).

Unlike the microprocessor chip, which TI and Intel Corporation had each

successfully built earlier in 1971, and which is used as the central

computing chip in present-day personal computers, the computer-on-a-chip is

especially suited to appliance and industrial control applications because

it contains a permanent on-chip program that directs the chip to perform a

dedicated function, such as controlling a microwave oven or tuning a

television.

After

months of work, Boone and his coworkers completed building the first working

computer-on-a-chip in the early morning hours of July 4, 1971. Two weeks

later, TI filed a patent

application,

which resulted in the series of patents issued, beginning in 1978, naming

Boone as the inventor.

Hyatt

never actually built a computer-on-a-chip, but based his claim to the

invention on a series of patent applications he filed with the Patent Office

in the 1970s and 1980s. In the Patent Office interference proceeding, he

claimed he filed the first patent application describing a

computer-on-a-chip in December 1970. After a review of tens of thousands of

pages of Hyatt's patent filings, however, the Patent Office determined that

Hyatt first mentioned the invention in an application that was not filed

until December 1977--six years after TI introduced the product.

In 1994, TI requested that the Patent Office publish Boone's patent application as an SIR rather than as an additional patent. An SIR gives official recognition to an invention, but does not entitle the inventor to collect royalties.

Texas Instruments Incorporates. Dallas, Texas (June 19, 1996)

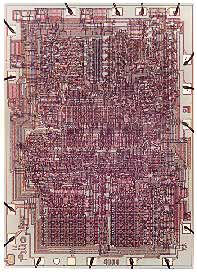

� TMS1000: The first available Microcontroller

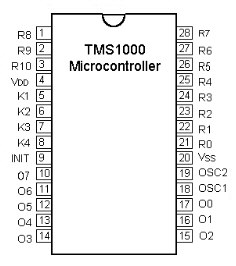

The

TMS1000 is actually a series of 4-bit Microcontrollers containing ROM, RAM,

I/O, & CPU on one chip produced by Texas Instruments. Find the original

press release here. The units are not

capable of expansion in any way. The highest clock frequency attainable by

the series is 0.4MHz. This results in a 2.5 microsecond clock cycle. All

instructions execute in 6 clock cycles. The devices were fabricated using

PMOS and required a single -15V supply.

The

TMS1000 is actually a series of 4-bit Microcontrollers containing ROM, RAM,

I/O, & CPU on one chip produced by Texas Instruments. Find the original

press release here. The units are not

capable of expansion in any way. The highest clock frequency attainable by

the series is 0.4MHz. This results in a 2.5 microsecond clock cycle. All

instructions execute in 6 clock cycles. The devices were fabricated using

PMOS and required a single -15V supply. The

only data input available is through the 4 bit K input lines. Input

instructions collect whatever signals are available on the input lines at

the time. Output data exist as 8 O lines and 11, 13, or 16 control, or R

lines. The accumulator and the status flag determine the bit pattern of the

O lines. This information has to be requested when the chip is produced.

What this means is that only 32 distinct patterns can be generated by the O

lines. The Y register determines which individual R control line is being

set or reset. All of these units have internal clock logic which can be

connected to an RC circuit with one end of the capacitor connected to Vss,

one end of the resistor connected to Vdd and the opposite ends of the

components connected to both OSC1 and OSC2. If an externally generated

signal is to be used, it must be connected to OSC1 while OSC2 is grounded.

The INIT (reset signal) should be held high for at least 6 clock cycles

after power is applied. Reset causes the Page Address and Page Buffer

registers to be loaded with binary ones. The O and R outputs as well as the

program counter are zeroed.

The

only data input available is through the 4 bit K input lines. Input

instructions collect whatever signals are available on the input lines at

the time. Output data exist as 8 O lines and 11, 13, or 16 control, or R

lines. The accumulator and the status flag determine the bit pattern of the

O lines. This information has to be requested when the chip is produced.

What this means is that only 32 distinct patterns can be generated by the O

lines. The Y register determines which individual R control line is being

set or reset. All of these units have internal clock logic which can be

connected to an RC circuit with one end of the capacitor connected to Vss,

one end of the resistor connected to Vdd and the opposite ends of the

components connected to both OSC1 and OSC2. If an externally generated

signal is to be used, it must be connected to OSC1 while OSC2 is grounded.

The INIT (reset signal) should be held high for at least 6 clock cycles

after power is applied. Reset causes the Page Address and Page Buffer

registers to be loaded with binary ones. The O and R outputs as well as the

program counter are zeroed.

Because of their limited requirements, hand-held calculators were one of the first consumer-oriented products to take advantage of the emerging LSI technology. After the initial, ad hoc designs, calculators have been implemented as stored-program computers. Today, most calculators consist of a single LSI computer chip plus a display. And the adoption of LSI technology was very rapid. For example, the TI-2500 Datamath calculator introduced in 1973, had 119 parts, of which 82 were electronic in nature. By 1976, the TI-1200 consisted of only 22 parts, of which only the calculator chip (a complete computer with programs) and display were electronic. This single-chip integration is made possible by the tightly specified user environment. Input (e.g., keyboard or magnetic card) and output (e.g., LED display, printer, or magnetic card) options are limited. Further, the input language (i.e., function per key) is also fixed.

The TMS1001 was the first LSI MOS

chip of the TMS1000 family used in the Texas Instruments SR-16

calculator.

The chip contains a microcomputer complete with a program ROM having 1,024

eight-bit words; a temporary storage RAM; input (from keypad); output (to

control keypad scan and LED display); and an oscillator (clock). The TMS1000

chip was designed to span a range of hand-held calculator products (from

four-function up through simple memory calculators). Since the chip had to

be customized with the ROM program appropriate to a product, other

programmable features were included to improve the chip's flexibility. This

programmability was provided by two programmable logic arrays (PLAs). The

output PLA converts five bits into twenty 8-bit output patterns in order to

conserve program space. These patterns are specified by the calculator

designer and represent different output patterns on a seven-segment display.

The second PLA is for instruction decoding. The chip provides 16

microinstructions, such as "gate register Y to ALU." Twelve of

these microinstructions form the fixed instruction set. The remaining

instructions can be formed by combining any of the 16 microinstructions.

Thus the instruction set can be specialized to improve ROM efficiency and

execution speed for a particular application. Several special features of

the microcomputer are aimed at the calculator application. The data paths

are 4 bits wide to allow serial processing of binary-code decimal (BCD)

digits. The arithmetic functions assume 2's complement integers, special

instructions can be formed to facilitate BCD arithmetic (e.g., add six to

accumulator for adjustment to legal BCD digits). Another BCD-oriented

feature is the RAM addressing, which provides for four words of sixteen

4-bit fields. While the SR-16 only displays eight digits, the extra can he

used as "guard" digits to maintain numerical precision or as

expansion space for future products with larger displays or exponent

displays. (Note that the BCD digit-serial data path allows for this

expansion by increasing the loop count on variable-length-dependent

operations.) The TMS 1000 applicability is primarily limited by ROM (program),

RAM (user-accessible internals and temporaries), speed, and number of I/O

pins. All the calculator functions are done by program. Two time-consuming

functions are display refreshing and keypad scanning. The monolithic

microcomputer must serially refresh the digits of the current display value

at a sufficiently high frequency to achieve "persistency." The

monolithic microcomputer must also serially examine keypad rows to see if

any keys have been depressed. Even simple functions, such as Add, can take

several instructions to execute, since BCD digits are addressed sequentially.

Due to limitations on the LSI chip density, certain architectural features

add to programming complexity:

The TMS1001 was the first LSI MOS

chip of the TMS1000 family used in the Texas Instruments SR-16

calculator.

The chip contains a microcomputer complete with a program ROM having 1,024

eight-bit words; a temporary storage RAM; input (from keypad); output (to

control keypad scan and LED display); and an oscillator (clock). The TMS1000

chip was designed to span a range of hand-held calculator products (from

four-function up through simple memory calculators). Since the chip had to

be customized with the ROM program appropriate to a product, other

programmable features were included to improve the chip's flexibility. This

programmability was provided by two programmable logic arrays (PLAs). The

output PLA converts five bits into twenty 8-bit output patterns in order to

conserve program space. These patterns are specified by the calculator

designer and represent different output patterns on a seven-segment display.

The second PLA is for instruction decoding. The chip provides 16

microinstructions, such as "gate register Y to ALU." Twelve of

these microinstructions form the fixed instruction set. The remaining

instructions can be formed by combining any of the 16 microinstructions.

Thus the instruction set can be specialized to improve ROM efficiency and

execution speed for a particular application. Several special features of

the microcomputer are aimed at the calculator application. The data paths

are 4 bits wide to allow serial processing of binary-code decimal (BCD)

digits. The arithmetic functions assume 2's complement integers, special

instructions can be formed to facilitate BCD arithmetic (e.g., add six to

accumulator for adjustment to legal BCD digits). Another BCD-oriented

feature is the RAM addressing, which provides for four words of sixteen

4-bit fields. While the SR-16 only displays eight digits, the extra can he

used as "guard" digits to maintain numerical precision or as

expansion space for future products with larger displays or exponent

displays. (Note that the BCD digit-serial data path allows for this

expansion by increasing the loop count on variable-length-dependent

operations.) The TMS 1000 applicability is primarily limited by ROM (program),

RAM (user-accessible internals and temporaries), speed, and number of I/O

pins. All the calculator functions are done by program. Two time-consuming

functions are display refreshing and keypad scanning. The monolithic

microcomputer must serially refresh the digits of the current display value

at a sufficiently high frequency to achieve "persistency." The

monolithic microcomputer must also serially examine keypad rows to see if

any keys have been depressed. Even simple functions, such as Add, can take

several instructions to execute, since BCD digits are addressed sequentially.

Due to limitations on the LSI chip density, certain architectural features

add to programming complexity:

RAM

addressing: Since instruction size is limited to 8 bits, there is not

enough room to specify an address in the instruction. Thus, a preloaded

register pair (X,Y) is assumed to contain the currently valid address when

executing the memory-reference instruction. The register can be updated by

using instructions with immediate operands or by incrementing.

Program

Counter (PC) incrementing: In order to save a separate

incrementer for the PC or trips through the ALU for updating, the PC update

is implemented by a pseudo-random sequence to go through all 64 states

produced by a feedback shift register such as is used in cyclic redundancy

codes. Thus only a shifter and several logic gates are required.

Instructions

with side effects: Certain instruction op codes have been selected so

that they can apply appropriate constants to the ALU and RAM. While this

saves ROM space for frequently used constants, it seems to make op code

selection difficult and add non-symmetry to the instruction format.

� All TMS1000 chips

The TMS1000 was introduced in 1974 and used in the SR-16 calculator. The following table summarizes the 15 different chips used in TI single-chip calculators.