What does it take to build a little 68000-based protoboard computer, and get it running Linux? In my case, about three weeks of spare time, plenty of coffee, and a strong dose of stubborness. After banging my head against the wall with problems ranging from the inductance of pushbutton switches to memory leaks in the C standard library, it finally works! I’ve built several other DIY computer systems before, but never took their software beyond simple assembly language programs. Having a full-fledged multitasking OS running on this ugly pile of chips and wires is a thrill, and opens up all kinds of interesting new possibilities. I’ve named this plucky little machine 68 Katy.

Hardware

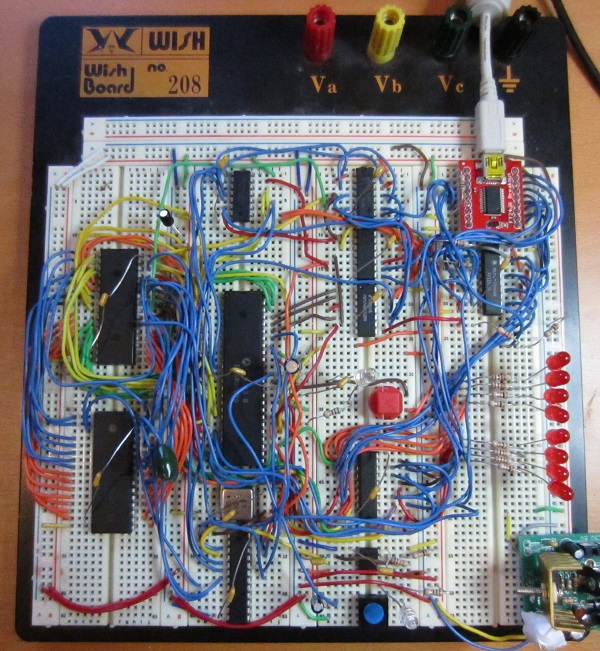

Here’s a look at the final version of the hardware. It took about a week to assemble and wire up all the parts on a solderless breadboard. The heart of the system is a Motorola 68008 CPU, a low-cost variant of the more common 68000, with fewer address pins and an 8-bit data bus. The CPU has 20 address pins, allowing for 1 MB of total address space. It’s paired with a 512K 8-bit SRAM, and a 512K Flash ROM (of which 480K is addressable – the remaining 32K is memory-mapped I/O devices).

The standard 68000 CPU has a 16-bit data bus, so it normally requires at least two 8-bit RAM chips and two 8-bit ROM chips. The 68008 requires fewer memory chips thanks to its 8-bit data bus, but the trade-off is that memory bandwidth is only half that of the 68000. Neither chip has any on-board cache, so half the memory bandwidth leads to roughly half the performance. My 68008 runs at 2 MHz (it was unstable when tested at 4 MHz), providing similar performance to a 1 MHz 68000. That’s pretty slow, even in comparison to 68000 systems from the early 1980’s, which were typically 8 MHz or faster.

An FT245 USB-to-FIFO module provides a communication link to another computer. On the external PC, it appears as a virtual serial port. Windows Hyperterm or another similar terminal program can be used to communicate with it, like an old VT100 terminal. On the 68 Katy side, the FT245 appears as a byte-wide I/O register mapped into the CPU’s address space. Reading from its address fetches the next incoming byte from the PC, and writing to the address sends a byte out to the PC. The FT245 has an internal 256-byte buffer, which helps smooth out the communication. When there’s an incoming byte waiting in the buffer, it triggers a CPU interrupt.

A 555 timer provides the only other interrupt source, generating a regular series of CPU interrupts at roughly 100 Hz. The initial version of the hardware had no timer interrupt, but I later discovered it was essential in order to get Linux working correctly.

The protoboard has eight LEDs for debugging, which are driven from a memory-mapped 74LS377 register. The rest of the protoboard is filled with assorted 7400 series parts and one PAL, which are used for address decoding, interrupt arbitration, and other basic glue logic.

Schematics? Forget it. Everything was built incrementally, one wire at a time, while staring at chip datasheets. It’s an organic creation.

Software

Once the hardware build was done, I began writing some simple test programs in 68K assembly language. Wichit Sirichote’s zBug monitor provided a good starting point for my own ROM-based monitor/bootloader. Using the monitor program, I was able to load other programs in binary or Motorola S-record format over the FT245 link, store them in RAM, and execute them. I was even able to get Lee Davison’s ehBASIC for 68000 working, which provided a few hours of fun.

One feature I could have added to the monitor program, but didn’t, was the ability to reprogram the Flash ROM. The ROM chip has a read/write input pin just like an SRAM, but writing to the Flash ROM is more complicated. The CPU needs to first write a magic sequence of bytes in order to unlock the ROM. Then it needs to write more magic bytes to tell the ROM which blocks to erase, followed by the new bytes to be written. Finally, it must poll the output of the ROM to learn when the erase and reprogram sequence is complete.

The monitor program could have updated itself, or any other data stored in ROM, by copying itself to RAM, then running from RAM while saving new data to Flash ROM. But I was lazy and never implemented that feature, so I had to physically pull the ROM chip from the protoboard and place it in an external EPROM programmer whenever I made a change – about 100 times over the course of the project. Ugh.

Linux

Inspired by a similar project, I decided that a simple monitor program and BASIC weren’t interesting enough, and I needed to run Linux on this hardware. It sounded interesting and exciting, but I really had no idea where to begin. I had plenty of experience as a Linux user (as well as other UNIX versions), but I knew nothing about how the kernel worked, or how to build it from source code, or to port it to new hardware. So the real adventure began there.

The first challenge was to learn how to build a Linux image for an existing machine. It seemed simple enough in theory – just download the source code from kernel.org or some other distribution tree, and compile it. Reality was more complicated, and there were many details that confused me, and build problems I was powerless to solve. It wasn’t easy, and I discussed the process in much more detail in this earlier post.

I chose to use uClinux, a Linux distribution designed for microcontrollers and other low-end hardware, particularly CPUs without an MMU and that can’t support virtual memory. Then I chose a very old version of uClinux, based on kernel 2.0.39, that dates all the way back to 2001! I configured it to disable nearly every single optional feature, including all networking support. This ancient code was my best hope for getting a Linux that would actually run in 512K of ROM and 512K of RAM.

Starting with the uClinux configuration for another 68000-based system, I updated the code to reflect the 68 Katy memory map, changed the system initialization code, and added a driver for the FT245. Describing those steps makes them sound simple, and they might have been for someone more experienced with Linux, but for me it was a challenge just to identify which files and functions needed to modified. Google wasn’t very helpful, since I was working with such an old version of the kernel, and the resources I found on building/porting Linux mostly weren’t applicable. I primarily relied on the Linux grep command to search through the thousands of kernel source files for strings of interest, then stared at the code until I could understand how it worked.

After about a week, I had something I was ready to test. And it worked, at least a little bit! It showed the first few lines of kernel output, but hung at “calibrating delay loop”. Aha, I needed a timer interrupt. Of course! I added a 555 timer and some extra interrupt logic, and was ready to try again.

The second attempt got further into the boot process, but failed to mount the memory-resident root filesystem. I was stumped for a while. After looking more carefully, I discovered that my linker script was mapping the root filesystem and BSS to the same address in RAM, and the earily initialization code was overwriting the filesystem with zeroes. And more fundamentally, I discovered that it wasn’t possible to fit all of Linux in 512K RAM, including the kernel code, static data, root filesystem, and dynamically allocated memory. Something had to be moved to ROM, or it was never going to work.

In the third attempt, I moved the root filesystem image to ROM, freeing up about 150K of RAM. And this kind of, almost worked! It booted, mounted the filesystem, and seemed to be working OK, but then suddenly it would land back at the monitor program prompt. Huh? I eventually tracked this one to the FT245 driver I’d written. I only implemented the minimal set of required driver functions, and the other optional functions were NULL entries in a function table somewhere. One of the functions I thought was optional proved to be required. When the kernel called it, it used a NULL function pointer, causing a jump to address 0, restarting my monitor program.

The fourth attempt was better. It spawned the init process, and ran the startup script, but died with out-of-memory errors before it completed. At the time, 68 Katy’s memory map was 256K ROM, 256K I/O devices, and 512K RAM. By shrinking the I/O space to 32K, I was able to increase the usable ROM to 480K, providing enough space to store the root filesystem image and the kernel code itself! This freed up another 251K of RAM.

The fifth attempt actually booted to a shell prompt! Now it was executing the kernel code directly from ROM. I was able to run a few commands, like ls and cat, but then the system would run out of memory and die. As I investigated, it looked like memory allocated from malloc() and do_mmap() was never beeing freed. Was this some kind of free list allocator I didn’t understand? No. It turns out I’d made a typo in a function called is_in_rom(), adding too many zeroes, causing the memory allocator to think all addresses were in ROM and so didn’t need to be freed. Then after fixing that, I discovered a small memory leak in the C library setenv() function. I never did solve that one, but instead just modified the programs that used it to avoid calling it.

My debugging method was primitive: lots of printk and printf statements sprinkled everywhere. Then pull the ROM chip, reprogram it in an external EPROM programmer, replace it in the protoboard, and try again.

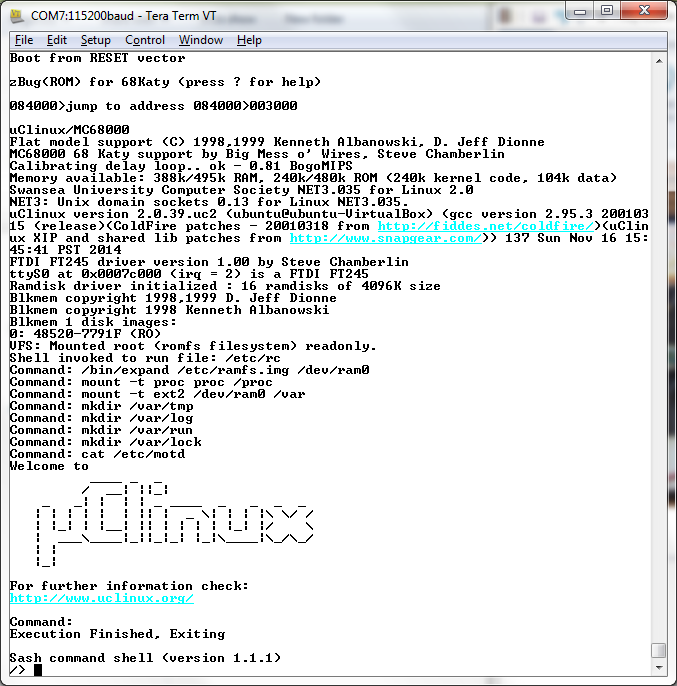

The sixth attempt finally worked. Two weeks after beginning my experiments with Linux, I had a working system! Here’s a screenshot of the boot sequence:

Watch the video for more details. I’m using a shell called sash, which has a few dozen common shell commands (like ls and cat) built directly into it. The root filesystem in ROM is read-only, and a small read-write filesystem is created in a RAM disk. The system supports multitasking, so it can run an LED blinker program in the background while still working in the Linux shell. It even has vi, and Colossal Cave Adventure!

It was an interesting journey. The Linux kernel still seems big and unwiedly to me, but no longer seems so scary as it did initially. It’s just an especially big program, and most of its pieces aren’t too difficult to understand if you open up the relevant source files and start reading.

Memory Requirements

So how much memory does it require to run a super-minimal uClinux system, with an old 2.0 kernel? If you follow my example and put as much as possible in ROM, it needs about 343K of ROM and 312K of RAM, or just 628K of RAM if you’ve got a bootloader that can fill RAM from some external source. My 68 Katy system is slightly heavier than that due to including vi and Adventure, but not by much. Here’s the breakdown:

ROM

- kernel code and read-only data (.text and .rodata segments) – 251K

- kernel initialized static data (.data segment) – 27K

- root filesystem – 189K

RAM

- kernel static data (.data and .bss segments) – 84K

- kernel dynamic allocations during boot-up – 104K

- RAM disk – 64K

- init and shell process allocations – 58K

- stack and exception vectors – 2K

Problems

The kernel always measures the CPU at 0.81 bogomips, regardless of the clock crystal I use. The 555 timer interrupt is independent of the CPU clock, so with a faster clock the bogomips calculation should measure more executions of the busy loop per timer interrupt. I’m not sure why it doesn’t, but it means any real-time calculations will be off.

The display in vi acts weird. Some lines appear prefixed with a capital H, and stray Unicode characters appear here and there. At first I thought this was a hardware bug, and I’m still not certain it isn’t. But I think it’s probably an issue with the way my terminal program (Tera Term) handles the ANSI escape sequences sent by vi. I tried all the different terminal settings available in Tera Term, and also tried a different terminal program, all with the same result.

What’s Next?

This 68008 system on a protoboard was intended to be only an experiment and proof-of-concept for the real 68 Katy, which I had planned to build on a custom PCB with a full 68000 CPU, a CPLD for glue logic, more RAM, an SD card, and ethernet. But this experiment was perhaps a bit too successful, and now I’m wondering if it really makes sense to go to the effort of building the “real” system if it’s going to be essentially the same thing, only faster. Of course the SD card and ethernet will add some interesting new elements, so maybe it’s fine. I probably need to sleep on the question for a few days.

One way of adding more spice to the next iteration of 68 Katy would be to include video output, so it could directly drive a monitor instead of being controlled through a serial terminal. I’ve done that once before, with BMOW 1, which had VGA output. It mostly worked, although the arbitration for video memory between the display hardware and the CPU was clunky and produced visible display artifacts. To take things further, I could even aim for DVI or HDMI video output, since VGA is a slowly dying standard.

The smart move is probably to stick with my original plan. Lots of extra features are cool, but also have a way of killing a project. I’d rather have something with 10 features and that works, than something with 20 features that I never finished or that collapsed under the weight of its complexity. But until then, excuse me while I go play some more Colossal Cave…

Files

The source code for my 68 Katy port of uClinux is available for download, as well as the toolchain I used to build it, the monitor/bootloader source, and a preconfigured VirtualBox machine image of Ubuntu 12.04 to host it all. Grab the files here. Have fun!