Normally, we can only catch a few shards of the shattered dreamscape; as much as we may try to cling onto the fragments of thoughts, feelings and sensations, they soon evaporate in the glare of our waking consciousness.

In contrast, McGregor’s tapes offer hundreds of hours of one man’s slumbers narrated in astonishing detail. The stories are full of eccentric characters like Edwina; they occupy a sinister place where a simple Lazy Susan can suddenly inspire a dangerous game of Russian roulette.

“It’s such a treasure trove of recordings – unlike anything that existed before,” says Deirdre Barrett at Harvard Medical School.

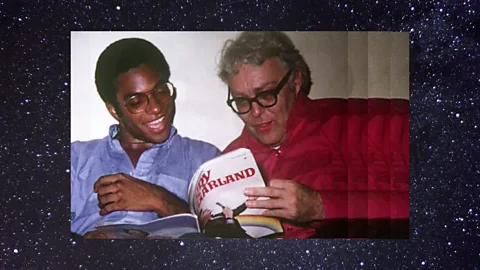

Peter De Rome/British Film Institute

Peter De Rome/British Film Institute

It was in New York in the 1960s that McGregor’s dreams began to overshadow his waking life. The aspiring songwriter was down on his luck and “couch surfing” at his friends’ flats in New York City – first the screen actor Carleton Carpenter, then the homoerotic film director Peter De Rome. (In fact, McGregor himself appears in De Rome’s film Mumbo Jumbo, albeit fully clothed.) “He was quite an affable and erudite individual, known to have a very sharp wit,” says Toronto-based poet and McGregor aficionado Steve Venright. Needless to say, his flatmates often found the habit more irritating than curious.

When McGregor moved upstairs into fellow songwriter Michael Barr’s flat on First Avenue, however, his “somniloquies” found a truly appreciative audience. Early each morning, Barr would creep into the living room and place a microphone near the head of the McGregor’s bed, and press record.

It’s like being famous for wetting your bed – Dion McGregor

Although 14% of us sleep-talk regularly, it’s normally little more than a few mumbled sentences. Barr, however, recorded stories of such detail that even McGregor was surprised with the content. Fascinated, Barr would often show them to his friends. “For Barr, these narratives were really a highlight of his life,” says Phil Milstein, a record producer who enjoyed a correspondence with Barr and McGregor in later life.

Eventually, the tapes caught the attention of the legendary Decca record label – who offered to put out a disc of their choice cuts. The result was an LP, The Dream World of Dion McGregor, which dropped in 1964, and a book published by Random House. Fearful that they might be part of an elaborate hoax, the publisher commissioned a psychiatrist to check up McGregor; as far as he could tell, McGregor was healthy, sane – and not just pretending.

Barr was delighted to have brought the strange tales to a wider audience (his later ambition was to write a musical based on the episodes), but McGregor felt somewhat embarrassed by the attention. “It’s like being famous for wetting your bed,” he said in one interview.

The recordings may not be to everyone’s taste, but they have caught the attention of Harvard’s Deirdre Barrett. She points out that sleep-talkers’ utterances do not always coincide with dreams – the speech seems more like a reflex without a story attached to it. In other cases, however, sleep-talkers do report dreams that match their recorded somniloquies very closely.

Barrett thinks this can probably be explained by a hybrid sleep state somewhere between the “rapid eye movement” (REM) sleep that normally hosts dreams, and a shadow of waking consciousness. As evidence for this, Barrett points to the work of A M Arkin, who measured the brain activity of sleep talkers as they slept in his lab. (Indeed, Dion McGregor may have been one of the subjects, though there is no firm evidence of this.) Sure enough, Arkin found that the constellation of active brain regions appeared to combine signatures of REM with greater activity in the motor cortex – an area that would normally be mute during sleep.

If you had to pull a scam it would seem an unlikely one – Deirdre Barrett

Of course, we can’t totally discount the possibility that McGregor was faking it – but given McGregor’s apparent bemusement at the recordings, Barrett is sceptical that’s the case. “I don’t think they even expected to make a lot of money from it,” she says. “If you had to pull a scam it would seem an unlikely one.”

In her first study on McGregor, Barrett’s team has analysed selections from Venright’s vast archive of transcripts to judge them on traits such as the detail of the plots, emotions, the friendliness and aggression of dream characters, as well as the presence of incongruities, other forms of bizarreness you might expect in dreams. As a comparison, they also rated 500 entries from dream diaries taken from men of McGregor’s age, in the 1960s. (Importantly, the people rating the reports had no idea who they were judging.)

Olivia Howitt

Olivia Howitt

As you might expect from hearing the recordings, Barrett found that McGregor’s vibrant personality came through particularly strongly in the somniloquies: within the episodes, he was either more aggressive and unkind, or much friendlier than the average dreamer.

Intriguingly, however, McGregor’s stories actually turned out to be less bizarre than the average dream. That’s not to say he didn’t sometimes have fantastical elements, as Barrett observed with the following example, in which he tries to mate a mermaid with a centaur.

A pterodactyl, yes, the unicorn, the griffin, dear, oh yes, well a mermaid doesn’t count, she’s out in the pool – Dion McGregor

“Oh, that doesn’t complete my collection at all! No! Oh no! Well let’s see, I have a dodo, and a rock, and a phoenix...oh dear! A pterodactyl, yes, the unicorn, the griffin, dear, oh yes, well a mermaid doesn’t count, she’s out in the pool! No... well, if she ever gets out I’m gonna mate her with the centaur! Yes! What do you think?! Certainly! Well, I don’t know. What do you think? Well, if you don’t mate them you know they’ll die off!”

The dream catcher

Clearly, McGregor’s brain was not simply constrained to the mundane and everyday. But within each story there is a certain internal logic; the plot is cohesive from start to finish, with fewer confusing shifts in scenes or characters over the course of the action. “They typically don’t have the bizarre jumps from one storyline to another – it’s just odd content,” says Barrett.

Barrett thinks this may be a result of the hybrid brain state, although she agrees it’s hard to know if it’s also due to McGregor’s idiosyncratic personality. In the future she wants to work with data collected by a phone app to record sleep talking on a much wider scale. Perhaps then we will know if McGregor’s sleep stories were truly the result of his uniquely creative mind – or if such detailed somniloquies are more common.

McGregor died in 1994, never living to see this renewed interest in his sleep-talking – though it’s unlikely he would have relished it. In any case, in later life he seems to have overcome his strange nocturnal habit.

“Meeting his life partner and moving to Oregon just seemed to change him,” says Venright. “Even though he never claimed to be fraught with anxiety, he surmised that maybe it was because he got it all out in sleep – and when he found himself at peace and happy, that’s when the sleep-talking subsided.”