About 30% of the victims of sexual harassment are men. About 20% of the perpetrators of sexual harassment are women.

Don’t believe me? In a Quinnipiac poll, 60% of women and 20% of men said they’d been sexually harassed. Opinium, which sounds like a weird drug, reports 20% of women vs. 7% of men. YouGov poll in Germany finds 43% of women and 12% of men. The overall rates vary widely depending on how the pollsters frame the question, but the ratio is pretty consistent.

The data on perpetrators is less clear. The best I can find is this Australian study finding that 21% of harassers are women. The German poll finds it’s 25%. I’m less confident on this one, but 20% seems like a conservative guess.

If you prefer anecdotes to data, you can sift through this Reddit thread with 2474 comments. For example:

I’m a junior ncm in the Canadian forces. I had a chief harass me daily which resulted in administrative actions when I tried resisting her abuse. My introduction to her was when she was telling the 20 or so people “Under her” that her dildos name is George…it went downhill from there and eventually she was groping me on the daily. I requested a geographic posting to get away from that lunatic and get an investigation underway but I was told by my WO that “these things happen for a reason”. Eight months later I was suicidal and that WO was signing my counselling and probation with her husband.

I went up to get a drink in a crowded bar and a rather large woman ruffled my hair and said ‘I like this one’. She then started thrusting into my backside. I wasn’t sure how to respond… I just kinda waited for it to stop. It was pretty uncomfortable and I felt kinda vulnerable. In the wake of all these sexual harassment stories, I looked back on this moment and considered for the first time that that was actual sexual harassment. Huh.

Don’t believe random Redditors, but do believe random bloggers? Then for what it’s worth I’ve been sexually harassed by two women, and I see no reason to think my experience is anything other than typical.

But then is it odd that so few of the recent high-profile victims of sexual harassment have been men, and so few of the high-profile perpetrators women? No. Everyone has made it clear from the start that they don’t want to hear about this. The viral Facebook message that started #MeToo – at least the one I saw – urged women to come forward with their stories of sexual harassment, and men to come forward with stories of times they perpetrated sexual harassment. The slogan “BELIEVE WOMEN” got enshrined into a mantra, pretty ominous if you’re a guy wondering whether people will believe your harasser’s story over yours. The mainstream media strongly discouraged men from coming forward with their own cases, with articles like I’m a man who has been sexually harassed – but I don’t think it’s right for men to join in with #MeToo. Their excuse was the usual – it’s not “structural oppression”, so it doesn’t count.

(The “structural oppression” model is false, by the way. Homosexual male harassment is more prevalent than the percent gay men in the population would imply, suggesting that gay men harass men more often than straight men harass women. The obvious explanation for gender differences in harassment has always been that men constitute 80% of sexual harassers for the same reason they constitute 83% of arsonists, 81% of car thieves, and 85% of burglars. Since most men are straight, most victims are women; when the men happen to be gay, they victimize men. Men probably get victimized disproportionately often compared to the straight/gay ratio because society views harassing women as horrible but harassing men as funny. If this theory is right then it’s men who are the structural victims, which means it’s your harassment that doesn’t count and you’re the ones who shouldn’t be allowed to talk about it. The “it only matters if it’s structural” game isn’t so much fun now, is it?)

Could this kind of ploy really shut up everybody? It didn’t have to. Men absolutely came forward with stories of harassment by high-profile women in Hollywood, and they were summarily ignored. By freak coincidence I came across this story from last month where Mariah Carey’s bodyguard accused her of sexually harassing him. Carey is much higher-profile than most of the men involved. But she didn’t even publish an apology, or a denial, or try to pick holes in his story. She just assumed nobody would care – and she was right.

Having silenced or ignored all men who might be sexually harassed, the media proceeded to treat sexual harassment in the most gendered way humanly possible, constantly reinforcing that only men can do it and only women can suffer it. The Guardian, being commendably honest about its priorities: We Must Challenge All Men About Sexual Harassment. Newsweek worries about how Women Are Attacked By Men In Almost Every Workplace. The Independent thinks the story is how powerful men seemingly never face the consequences of their actions toward women.

On the meta-level, the same publications pushed the narrative that men can’t possibly understand sexual harassment, or men will never believe accusers’ stories, or men refuse to believe other men can be harassers. The Guardian writes about Men Who Are Silent After #MeToo, and the Washington Post about how Some Men Disagree About What Counts As Sexual Harassment. Do any women disagree about what counts as sexual harassment? Yes, the stats show that they disagree exactly as much as the men do – but who cares? The story is that women are always victims and totally understand exactly what’s going on, and men are always perpetrators with their fingers in their ears denying that a problem exists. We are told to worry about Why Women Don’t Report Sexual Harassment (against themselves) but about Why Men Don’t Speak Up About Sexual Harassment (that they see happening against women). Needless to say, every line of evidence we have shows men are less likely to report harassment that happens to them than women are.

Is this really that bad? Might the 3:1 ratio justify focusing on women? Our society already has an answer to this, and in every other case, the answer is no.

I mean, for one thing, we’re telling people to stop using the phrase “pregnant mothers” since sometimes transgender men get pregnant. It seems kind of contradictory to think of this as a pressing issue, but also think that the fact that only 30% of harassment victims are men means that we should always use female pronouns for generic harassment victims, and always generically call perpetrators “males in position of power”.

But there’s also a deeper issue. Suppose I write about how we need to do more to support the victims of terrorism. Sounds good. But what if I write about how we need to do more to support the Christian victims of Muslim terrorism? Sounds…like maybe I have an agenda. If I write story after story about how Christians need to be on the watch out for Muslim terrorists, but Muslims need to be on the watch out for other Muslims being terrorists, and if I tell Muslim victims of Christian terrorism to stay silent because that’s not “structural oppression” – then that “maybe” turns to “obviously”. This is true even if the numbers show terrorists are disproportionately Muslim.

Or suppose I write about how we need to do more to help the victims of crime. Again, sounds good. What if I write about how we need to do more to help white victims of black criminals? Again, this does not sound so good, unless you happen to be Richard Spencer. If I write articles like “We Must Challenge All Blacks About Crime” or “Whites Are Attacked By Blacks In Almost Every Neighborhood”, then probably I am Richard Spencer. This is true regardless of whether the statistics show a racial skew in perpetrators. Nobody would accept “yeah, but I’m right about what the ratio is” as an excuse that your motives were pure.

Frames like “We need to do more to support the victims of terrorism” are an attempt to come together to stop an important social problem. Frames like “We need to do more to support the Christian victims of Muslim terrorism” are a hit job on the outgroup. Do I think that sexual harassment is being used this way? I have no other explanation for the utter predominance of genderedness in the conversation.

I’ve previously talked about two visions of social justice. The first vision tries to erase group differences to create a world free from stereotypes and hostility. The second vision tries to attack majority groups and spread as many stereotypes as possible about them in the hopes that the ensuing hostility raises the position of minorities. I think the gendered nature of the conversation is deliberate, being done with exactly this vision and for exactly the same reason some people talk about “Christian victims of Muslim terrorism”. I think this is unfortunate. Why?

Because it ensures that nobody has more than half the picture.

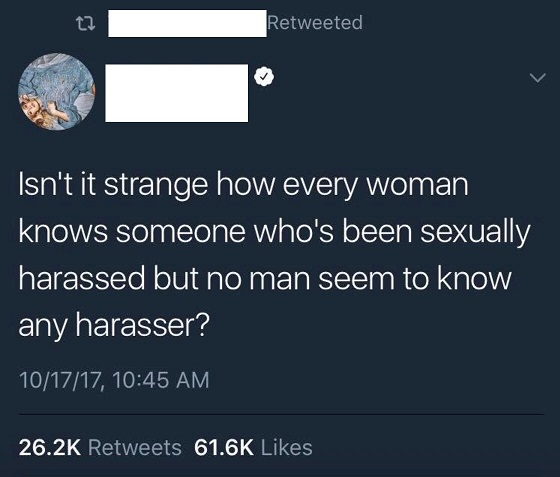

I wonder if the woman who wrote this knows any of her close female friends who are harassers?

I mean, statistically, some of them have to be. According to the German study, 6% of women admit to being harassers. Know more than a dozen women? One of them’s probably a harasser. Don’t know which one it is? Congratulations, now you can understand why some men don’t know which of their same-gender friends is a harasser either.

There’s a truism that rich people can’t understand what it’s like to be poor. Why don’t you just get a minimum wage job, earn $7/hour = $60/day = $18000/year, save half of it, after few years you’ve got enough to go to a cheap college and get your ticket to the middle class? It’s possible to figure out what’s wrong with this from a third-person perspective, but it’s much easier to get the first-person perspective and be like “Oh, I guess that’s what it’s like”.

The reason this tweeter can’t understand how it’s hard to believe that your friends are sexual harassers is because she’s never tried to consider the question from a first-person perspective. I predict the sort of person who makes tweets like this is exactly the sort of person who would say “How dare you say any of my female friends could be sexual harassers! Don’t you even understand structural oppression?!”

Likewise, do you think this woman knows any men who are victims of sexual harassment? If you were a man who’d been sexually harassed, would you admit it to this woman and expect a sympathetic ear? Once she contemplates why she doesn’t know so many men who have been sexually harassed, maybe she’ll understand why some men don’t know so many women.

But more than that, if men were included in the conversation – if it were understood that a man who was sexually harassed by a female Hollywood celebrity would have the slightest chance at a fair hearing – then maybe they would feel like it was more in their self-interest to support victims.

And if women were included in the conversation as potential perpetrators, they might understand why some people find it scary when people lose their careers over unsubstantiated allegations.

Instead, since we’ve chosen a narrative where one side can only ever be a victim and the other can only ever be perpetrators, we’ve made it impossible for anyone to see both perspectives. Self-interested men worry only about how to avoid allegations, self-interested women worry only about how to make sure all allegations are believed, and nobody worries about how to make a system where they expect fair treatment no matter which role they find themselves in.

The solution is to treat harassment the same way we treat terrorism. It’s something that’s bad. It’s something that some groups might do more often than other groups, but this is not the Only Relevant Factor About It, and we are suspicious of people who seem more interested in stereotyping the groups involved than in making sure everyone of every group gets justice.

And once we get good evidence that someone is guilty, we have drones bomb their house. Seriously, the terrorism model has a lot going for it.