What is an experiment?

The gold standard in scientific fields is the randomized experiment. That’s when you have some “treatment” you want to impose on some population and you want to know if that treatment has positive or negative effects. In a randomized experiment, you randomly divide a population into a “treatment” group and a “control group” and give the treatment only to the first group. Sometimes you do nothing to the control group, sometimes you give them some other treatment or a placebo. Before you do the experiment, of course, you have to carefully define the population and the treatment, including how long it lasts and what you are looking out for.

Example in medicine

So for example, in medicine, you might take a bunch of people at risk of heart attacks and ask some of them – a randomized subpopulation – to take aspirin once a day. Note that doesn’t mean they all will take an aspirin every day, since plenty of people forget to do what they’re told to do, and even what they intend to do. And you might have people in the other group who happen to take aspirin every day even though they’re in the other group.

Also, part of the experiment has to be well-defined lengths and outcomes of the experiment: after, say, 10 years, you want to see how many people in each group have a) had heart attacks and b) died.

Now you’re starting to see that, in order for such an experiment to yield useful information, you’d better make sure the average age of each subpopulation is about the same, which should be true if they were truly randomized, and that there are plenty of people in each subpopulation, or else the results will be statistically useless.

One last thing. There are ethics in medicine, which make experiments like the one above fraught. Namely, if you have a really good reason to think one treatment (“take aspirin once a day”) is better than another (“nothing”), then you’re not allowed to do it. Instead you’d have to compare two treatments that are thought to be about equal. This of course means that, in general, you need even more people in the experiment, and it gets super expensive and long.

So, experiments are hard in medicine. But they don’t have to be hard outside of medicine! Why aren’t we doing more of them when we can?

Swedish work experiment

Let’s move on to the Swedes, who according to this article (h/t Suresh Naidu) are experimenting in their own government offices on whether working 6 hours a day instead of 8 hours a day is a good idea. They are using two different departments in their municipal council to act as their “treatment group” (6 hours a day for them) and their “control group” (the usual 8 hours a day for them).

And although you might think that the people in the control group would object to unethical treatment, it’s not the same thing: nobody thinks your life is at stake for working a regular number of hours.

The idea there is that people waste their last couple of hours at work and generally become inefficient, so maybe knowing you only have 6 hours of work a day will improve the overall office. Another possibility, of course, is that people will still waste their last couple of hours of work and get 4 hours instead of 6 hours of work done. That’s what the experiment hopes to measure, in addition to (hopefully!) whether people dig it and are healthier as a result.

Non-example in business: HR

Before I get too excited I want to mention the problems that arise with experiments that you cannot control, which is most of the time if you don’t plan ahead.

Some of you probably ran into an article from the Wall Street Journal, entitled Companies Say No to Having an HR Department. It’s about how some companies decided that HR is a huge waste of money and decided to get rid of everyone in that department, even big companies.

On the one hand, you’d think this is a perfect experiment: compare companies that have HR departments against companies that don’t. And you could do that, of course, but you wouldn’t be measuring the effect of an HR department. Instead, you’d be measuring the effect of a company culture that doesn’t value things like HR.

So, for example, I would never work in a company that doesn’t value HR, because, as a woman, I am very aware of the fact that women get sexually harassed by their bosses and have essentially nobody to complain to except HR. But if you read the article, it becomes clear that the companies that get rid of HR don’t think from the perspective of the harassed underling but instead from the perspective of the boss who needs help firing people. From the article:

When co-workers can’t stand each other or employees aren’t clicking with their managers, Mr. Segal expects them to work it out themselves. “We ask senior leaders to recognize any potential chemistry issues” early on, he said, and move people to different teams if those issues can’t be resolved quickly.

Former Klick employees applaud the creative thinking that drives its culture, but say they sometimes felt like they were on their own there. Neville Thomas, a program director at Klick until 2013, occasionally had to discipline or terminate his direct reports. Without an HR team, he said, he worried about liability.

“There’s no HR department to coach you,” he said. “When you have an HR person, you have a point of contact that’s confidential.”

Why does it matter that it’s not random?

Here’s the crucial difference between a randomized experiment and a non-randomized experiment. In a randomized experiment, you are setting up and testing a causal relationship, but in a non-randomized experiment like the HR companies versus the no-HR companies, you are simply observing cultural differences without getting at root causes.

So if I notice that, at the non-HR companies, they get sued for sexual harassment a lot – which was indeed mentioned in the article as happening at Outback Steakhouse, a non-HR company – is that because they don’t have an HR team or because they have a culture which doesn’t value HR? We can’t tell. We can only observe it.

Money in politics experiment

Here’s an awesome example of a randomized experiment to understand who gets access to policy makers. In an article entitled A new experiment shows how money buys access to Congress, an experiment was conducted by two political science graduate students, David Broockman and Josh Kalla, which they described as follows:

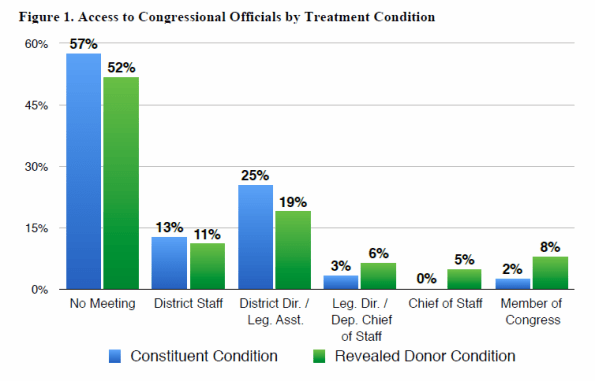

In the study, a political group attempting to build support for a bill before Congress tried to schedule meetings between local campaign contributors and Members of Congress in 191 congressional districts. However, the organization randomly assigned whether it informed legislators’ offices that individuals who would attend the meetings were “local campaign donors” or “local constituents.”

The letters were identical except for those two words, but the results were drastically different, as shown by the following graphic:

Conducting your own experiments with e.g. Mechanical Turk

You know how you can conduct experiments? Through an Amazon service called Mechanical Turk. It’s really not expensive and you can get a bunch of people to fill out surveys, or do tasks, or some combination, and you can design careful experiments and modify them and rerun them at your whim. You decide in advance how many people you want and how much to pay them.

So for example, that’s how then-Wall Street Journal journalist Julia Angwin, in 2012, investigated the weird appearance of Obama results interspersed between other search results, but not a similar appearance of Romney results, after users indicated party affiliation.

Conclusion

We already have a good idea of how to design and conduct useful and important experiments, and we already have good tools to do them. Other, even better tools are being developed right now to improve our abilities to conduct faster and more automated experiments.

If we think about what we can learn from these tools and some creative energy into design, we should all be incredibly impatient and excited. And we should also think of this as an argumentation technique: if we are arguing about whether a certain method or policy works versus another method or policy, can we set up a transparent and reproducible experiment to test it? Let’s start making science apply to our lives.