We all owe [Richard Stallman] a large debt for his contributions to computing. With a career that began in MIT’s AI lab, [Stallman] was there for the creation of some of the most cutting edge technology of the time. He was there for some of the earliest Lisp machines, the birth of the Internet, and was a necessary contributor for Emacs, GCC, and was foundational in the creation of GPL, the license that made a toy OS from a Finnish CS student the most popular operating system on the planet. It’s not an exaggeration to say that without [Stallman], open source software wouldn’t exist.

Linux, Apache, PHP, Blender, Wikipedia and MySQL simply wouldn’t exist without open and permissive licenses, and we are all richer for [Stallman]’s insight that software should be free. Hardware, on the other hand, isn’t. Perhaps it was just a function of the time [Stallman] fomented his views, but until very recently open hardware has been a kludge of different licenses for different aspects of the design. Even in the most open devices, firmware uses GPLv3, hardware documentation uses the CERN license, and Creative Commons is sprinkled about various assets.

If [Stallman] made one mistake, it was his inability to anticipate everything would happen in hardware eventually. The first battle on this front was the Tivoization of hardware a decade ago, leading to the creation of GPLv3. Still, this license does not cover hardware, leading to an interesting thought experiment: what would it take to build a completely open source computer? Is it even possible?

A Thought Experiment

Although open source doesn’t really apply to hardware itself, would it be possible to build a computer where every single line of code is available? Is it possible to build a complete computer from only printed documentation and a keyboard? Yes, for varying values of computer.

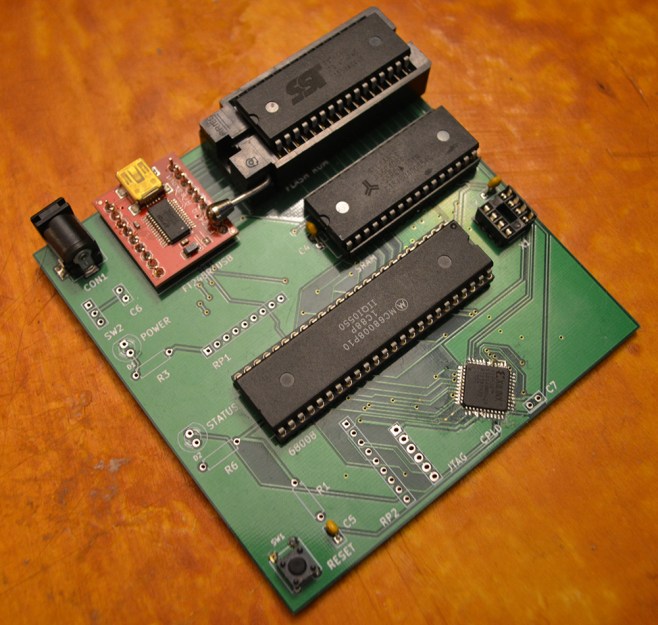

We can start with the simplest case, the most basic computer anyone could possibly build. Fortunately homebrewers have this type of build on lockdown. The simplest open source computer would probably be based on the 6502 CPU, with a few handfuls of RAM and ROM, tied together with 74-series glue logic. Video could be done with a Motorola 6847 video display generator, and input through a keyboard could be done with a 6522 VIA.

For software, there are dozens of choices to choose from. Forth, Basic, and CP/M have been built for a computer like this. With just a few bytes in ROM, it’s rather easy to build a completely open source computer with everything – firmware, schematics, and all program code – open for inspection.

Starting at the bottom is the easy way to build a completely open source computer, but it doesn’t make for a good machine. WiFi is out of the question, serial ports are the best networking you’ll get, and any modern workflow is completely impossible. What about starting at the top and working our way down? Let’s extend this thought experiment to taking a modern computer and paring everything down until it becomes an open source, usable computer.

The Usable Open Source Computer

Intel is right out. The Intel Management Engine (ME) is a small coprocessor embedded in every Intel PCU made since 2006. This chip has access to the cryptography engine, the ROM, RAM, and network access. It is a complete computer by itself, and very few people know how it works. While it makes a perfect backdoor, it goes against every open source ideology, and won’t be found in a completely open source laptop.

Going even further back the Intel chip timeline, every x86 chip from the 8080 onwards contains microcode, low-level software that tells the circuitry how to behave for each instruction. Microcode is found in nearly every CPU architecture of the last 20 years with one significant exception: ARM chips.

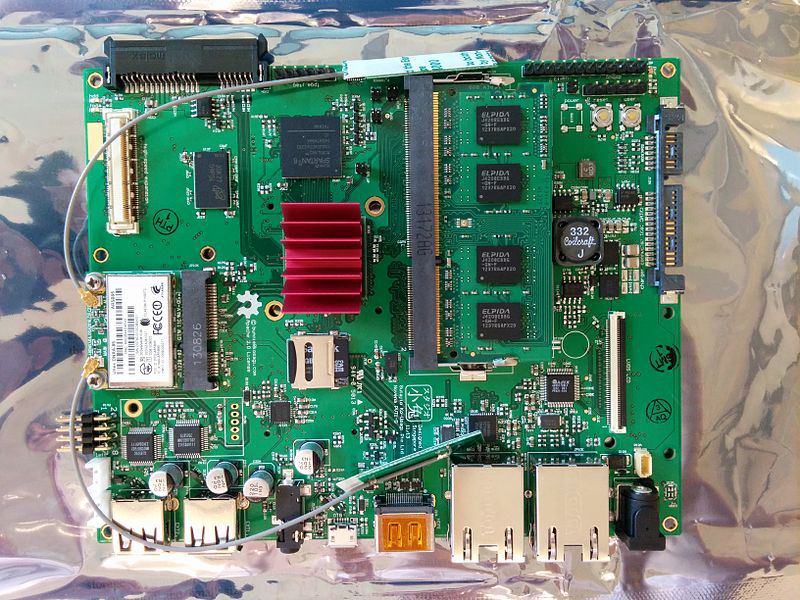

[Bunnie], the engineer behind the Chumby and the original XBox hack, built himself an open source laptop. It’s called the Novena, and after three years this laptop is finally making its way into the hands of its crowdfunding supporters. The Novena is built on Freescale’s i.MX6 chip, a quad-core ARM Cortex A9 running at 1.2 GHz. This CPU does not have any microcode, and the entire datasheet and programming manual is available from Freescale without an NDA. There are very few powerful processors out there that do not require an NDA, making [Bunnie]’s choice of chips obvious.

Despite one of the most open CPUs on the market, not all is Free in the Novena. Choice of WiFI card is very much limited because of binary blobs, and 3D acceleration though the Vivante GC2000 GPU cannot be used for the same reasons. Still, the Novena is the most usable open source and open hardware computer in existence.

That said, the Novena is just a motherboard, and a computer is much more than a piece of fiberglass and copper. There are hard drives, monitors, keyboards, and even webcams to consider.

Keyboards And Webcams And Hard Drives

If the goal of an open source computer is making yourself secure from attackers, you must consider everything attached to the computer. This includes peripherals, drives, and everything else that turns a large circuit board into a Facebook machine.

While the Novena might be the first usable open source computer, the peripherals are not. The recommended keyboard to be used with the Novena is a Lenovo keyboard, basically a Thinkpad keyboard repackaged into a USB desktop keyboard, torn apart, and thrown into a laptop chassis. It works, and until the mechanical keyboard community rediscovers Cherry ML switches, it’s the best we’re going to have.

While the Novena might be the first usable open source computer, the peripherals are not. The recommended keyboard to be used with the Novena is a Lenovo keyboard, basically a Thinkpad keyboard repackaged into a USB desktop keyboard, torn apart, and thrown into a laptop chassis. It works, and until the mechanical keyboard community rediscovers Cherry ML switches, it’s the best we’re going to have.

Similarly, the best way to put a webcam on the Novena is through USB. This is a problem. In 2014, BadUSB came to the community’s attention, and it means we are screwed. BadUSB adds nefarious abilities to the microcontroller in any USB device, allowing an attacker into a computer over a spoofed Ethernet connection. As long as a BadUSB-infected keyboard or webcam is plugged in, the computer is at risk. Surprisingly, a BadUSB attack is one of the easier ones to counter with open source; building a USB keyboard is as easy as programming an Arduino, and building a USB webcam is possible with smaller ARM chips. To date, though, I haven’t seen many arguments for open sourcing peripherals in the light of BadUSB.

![[Sprite_TM]'s hard drive hack from OHM2013](https://hackaday.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/hacking-hard-drive-controllers.jpg?w=400)

If keyboards and mice are easy to build under the auspices of open source, hard drives are not. Inside even the most basic hard drives are triple core controller chips that are nearly impregnable to any code inspection.

Nearly impregnable doesn’t mean impossible, and again, the hardware community lays the groundwork for an open source hard drive. At OHM2013, [Sprite_TM] gave a presentation on reverse engineering hard drive controller boards. While this is a project that has no precedent, it also has no antecedent; it appears no one really cares about the software that’s running on a hard drive. This is a little surprising, as the hard drive contains all the data on a computer. That said, you can now install Linux on a hard drive in the wierdest way you can imagine.

Stallman’s Solution

With the near impossibility of a completely open source computer, one has to wonder what [Stallman] uses. This is well documented. It’s an old Thinkpad loaded up with the Libreboot open source firmware. The drive in this computer is surely running proprietary code, and the laptop’s keyboard is a USB device that could be compromised.

It’s not an ideal solution by any measure, and this presents the largest obstacle to an ecosystem of open source hardware that matches the diversity of open source software. If anything, not considering hardware in the creation of GPL is [Stallman]’s one mistake. We’ll eventually get to the point where you can inspect all the code running on every peripheral connected to a computer, but it won’t be soon.