analysis A treasure trove of previously confidential documents pertaining to the Government’s data retention policy and released this week under Freedom of Information laws display an astonishing technical ineptitude on the part of the Attorney-General’s Department with respect to the controversial project.

For most Australian residents even casually concerned about the encroachment of government surveillance into their privacy rights, the term ‘data retention’ has the potential to deliver a note of terror, or at least mild anxiety. Conceived behind closed doors by the Federal Attorney-General’s Department in the years from around 2008, first revealed publicly in mid-2010 and now the subject of a fraught parliamentary committee process, data retention is the Big Bad of government surveillance. All your phone calls, all your emails, and potentially even all your web site visits and social networking interactions; tracked, archived, and made available for casual browsing by law enforcement authorities; sometimes without even a warrant.

But if you believe some of the revelations contained in an astonishing series of confidential documents extracted by the Pirate Party from the clutches of the Attorney-General’s Department this week … many of the key players pushing the policy in the Federal Government may not have a very solid grasp on the technology behind it.

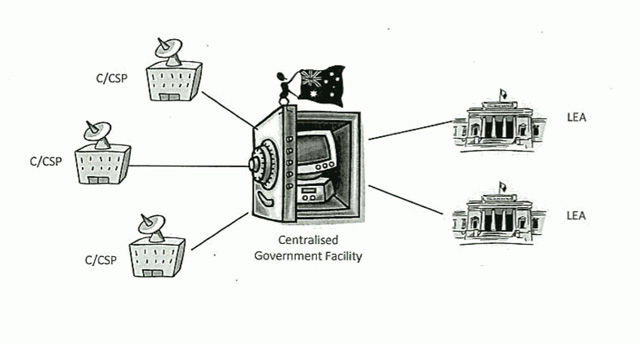

Take this network operating model which the Attorney-General’s Department put together in 2009 to distribute to Australian ISPs as one example of how a data retention system could work in practice:

The first thing the observer may notice is that there’s something incredibly macabre about the fact that the Attorney-General’s Department went to the effort of producing such a cute diagram to represent such a disturbing program, complete with an ant-like figure waving an Australian flag sitting on a cute PC locked in a safe to illustrate its planned “Centralised Government Facility” for data retention. (a name that would not have been out of place in Stalin’s Soviet Russia). What kind of person dresses up an Orwellian government surveillance program with cute icons?

But the more important fact is how frighteningly naive such a depiction is.

iiNet, only the third-largest ISP in Australia, has publicly estimated that the cost to its own business of delivering the data retention scheme conceived by the Attorney-General’s Department, which would store up to two years’ worth of Australians’ data, would soak up some 20,000 terabytes and cost some $60 million to administer.

The mind boggles when you start to consider how much more data Optus and Telstra, both substantially larger than iiNet, would need to store in such a facility, and how much it would cost. Telstra certainly seems to think it would be prohibitively expensive. The sheer process of storing and organising that much data would doubtless soak up hundreds of jobs and hundreds of millions of dollars. And that’s if it even worked at all. Australia’s Governments have repeatedly shown they have poor governance skills when it comes to implementing massive IT projects (Queensland Health, anyone?) and securing their own infrastructure (see examples here, here and here). When literally all of Australia’s communications is in the picture, how much more frightening that picture must be. And let’s not forget that other great storehouse of sensitive Australian information, the Personally Controlled Electronic Health Record project, was hacked before it even launched.

Hardly the cute and breezy picture the Attorney-General’s Department paints in its diagram.

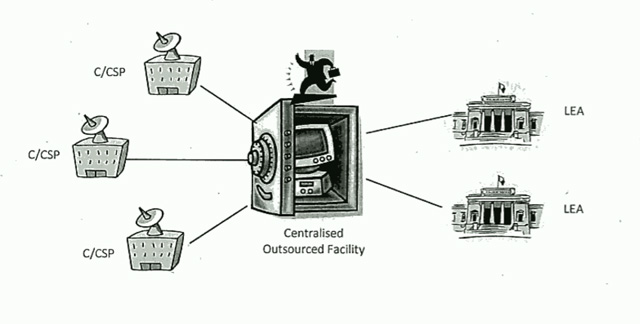

Similarly naive is the next model the department proposed; where an outsourcer would control the data storage. Again, here the same technical limitations arise; but there are also others; controlling the outsourcer itself. Again, here Australian Governments have shown themselves to have a poor track record when it comes to governance of such an outsourcing relationship.

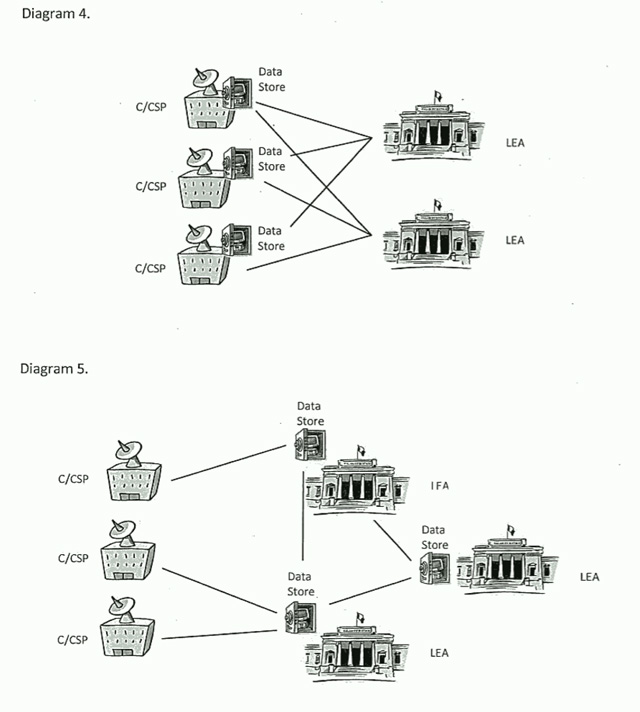

And then things get worse. We start to get into composite situations; ISPs, outsourcers and law enforcement entities all storing data; with these collossal datasets being “interlinked” and with data being swapped all over the place. Charming. Again, data transferral on this scale is far from a trivial task. The glibness of these diagrams starkly illustrates that the Attorney-General’s Department simply has no idea what it is talking about when it comes to the technical complexities of managing huge datasets.

“Do you favor any of the previously described models?” the Attorney-General’s Department glibly asks ISPs at the conclusion of its consultation paper. “If not, additional suggestions are welcomed.” The mind boggles. This is total government surveillance — conducted cowboy-style.

Later on, other documents reveal that in 2009, the Attorney-General’s Department had not determined “who will pay” for the whole deal — but that existing cost-sharing arrangements in telecommunications interception could apply. Again, this displays an incredible naivity surrounding the Attorney-General’s Department’s understanding of the costs involved. Under current TI legislation, Australian ISPs simply do not spend tens to hundreds of millions of dollars satisfying these kinds of government requests.

We’re talking here about a cost and IT infrastructure change from an existing telecommunications scheme in which Australian telcos and ISPs respond collectively to interception requests in the order of several hundred thousand per year, to a system in which every one of the billions of telephone and Internet interactions Australians conduct every year are logged. Its documents reveal the Attorney-General’s Department doesn’t quite seem to realise the exponential scale of telecommunications interception it’s planning with its data retention regime.

By 2011, the Attorney-General’s Department was beginning to realise the difficulty of some of these issues, as ISPs made their views clear (all still behind closed doors, of course). Meeting notes from an “industry forum” held by the Department on the issue note that “costs is a big factor” (sic), but by then other issues had started to raise their heads.

The same document notes that the privacy issues associated with the (hideously cute) “Centralised Government Facility” mentioned earlier would be “insurmountable”. Wow. It doesn’t take a rocket scientist to work out that if you collate all of Australia’s telecommunications data in one place, it will eventually be hacked — especially if the facility was maintained by the Government itself. And that’s not even counting illicit access by staffers who already have approved access to the data. Want to find out if your wife is cheating on you? Have a mate at the “Centralised Government Facility”? No problem. Have him pull a copy of her telephone, email and social networking records. That ought to do it. God knows this kind of thing goes on in the normal Police force on a regular basis.

But again, the next sentence in that document reveals the same deep technical naivity, claiming that such issues could be overcome “with additional security”, and a “spoke and hub arrangement”. Yeah, right. Is there any level of security which could be sufficient, for this kind of project?

Another factor mentioned was that communications technology itself was rapidly changing. Forget Skype, which had been around for years by then; one of the more pressing issues mentioned in the documents was Apple’s revelation in October 2011 of iMessage; a simple instant message protocol that would start replacing the easily trackable SMS format on many iPhones. It doesn’t appear as though the Attorney-General’s Department quite knew what to do about this kind of thing; telcos and ISPs wouldn’t be tracking the IP-based iMessages, after all.

But again, here we must question the incredible naivity of the department. iMessage is nothing new … online, IP-based message protocols had, by 2011, been around for several decades. Perhaps the department could have considered the 1996 launch of the now-defunct ICQ platform, for example, which has never been able to be tracked for telecommunications interception purposes. And there are thousands of other examples of how Internet-based technologies were disrupting carrier telecommunications models.

Written between the lines are other problems. The department’s document mentions that “destruction clauses” for the retained data “would be good” — presumably every year, a year’s worth of data would be deleted.

But, as Google has learnt to its pain over the past several years, the permanent deletion of sensitive data is no easy matter. In a practical sense, how is anyone supposed to go about permanently deleting some 20,000 terabytes of data each year (and remember, that’s just for iiNet)? Magnetic hard disks, the most common storage method, will always retain some of the data they have stored unless completely physically destroyed; and there’s also the fact that the most secure deletion routines (which would surely need to be used in this case) which leave the disk intact consume a great deal of time.

Ever done a low-level format of your hard disk, ‘zeroing’ it out? Now multiply that by a figure in the hundreds of thousands (millions?) each year. Not precisely an easy task.

Then there’s the documents’ curious mention of the fact that “in a converged society, IP address is the most useless identifier, because it will change as you roam”. This is true: IP addresses have long been discredited as a source of hard identification online, as they can be assigned or dropped at will. However, more disturbing is the documents’ mention of a “MAP address” as being more useful. We can take this as an error; most likely the department was referring to the ‘MAC address’ which all IP network devices use as a hardware identifier.

This mention is not concerning because it’s scary that the Government might be able to trace your actions online by your device’s (phone, laptop, tablet, PC, etc) MAC address. It’s concerning because Australian studies have repeatedly emphasised directly to the Attorney-General’s Department that MAC addresses are also a poor method of identification.

Take this 2004 paper by scholars at Swinburne University of Technology’s Centre for Advanced Internet Architectures (PDF), for example. It states baldly:

“In this paper we report on our investigations into the feasibility of using MAC addresses rather than IP addresses as an identifier in Lawful Interception. We found that MAC address interception in PPPoE and Broadband Ethernet environments can be very easily subverted. Consequently, we believe that MAC based interception is a poor option for lawful interception.”

We know that AGD must have been aware of this paper, because Electronic Frontiers Australia directly quoted the paper in its submission to a Senate inquiry into the then-Telecommunications Interception Act in 2006. Furthermore, the Law Council of Australia’s submission into the 2008 Inquiry into an amendment bill (PDF) at the time to the same act (funny how often Australia’s telecommunications interception regime gets amended, isn’t it) also notes it has concerns about the use of MAC addresses as identifiers.

And yet AGD was still discussing MAC addresses as identifiers in 2011. Hell, it probably still is.

So how does this kind of thing happen? How does a group of bureaucrats demonstrate so much technical naivety about this kind of massive technology project to track almost every aspect of Australia’s telecommunications; a project which inherently requires the most adept of technical competence? A project which clearly requires an experienced project governance team, high-level support from chief information officer- and chief security officer-level staff and massive financial resources? The answer is clear: The public servants behind this project do not have the technical experience or competence to implement it.

The two most high-profile AGD public servants behind the project are Catherine Smith, assistant secretary, telecommunications and surveillance law branch, and Wendy Kelly, director of the same branch. To be honest, we know very little about this pair; for all that they are the public face of a project generally considered to be one of the most sinister and ill-considered efforts that any Australian Government has ever come up with. There are no online biographies for these two; no articles laying out their principles; no photos, no LinkedIn profiles; almost nothing, in fact, apart from sporadic appearances before Senate committees which they only reluctantly attend.

But if they are like many of the other senior bureaucrats at AGD, it’s possible to make a decent guess at their background. They’re probably lawyers or have a background in law enforcement and public administration. How do we know this? Just look at everyone else who runs things at AGD.

I don’t know for sure that the department’s secretary, Roger Wilkins (you remember, the bureaucrat who set up the secret anti-piracy meetings between the ISP and content industries) is a lawyer, but he’s certainly been involved in plenty of law reform in his time in government. Deputy Secretary Elizabeth Kelly is a former lawyer and has worked in attorney’s and justice departments for years. Deputy Secretary David Fredericks is a lawyer, and the department’s other Deputy Secretary, Tony Sheehan, has a background in addressing issues such as “terrorism and people smuggling”.

Check out their biographies. Do these look like the kinds of people who, if they were overseeing a technology project of gargantuan proportions, would know what they were doing? Not really. It’s not their fault, but they just don’t seem to have the technical experience required. And they probably don’t understand all of what Kelly, Smith, AFP cybercrime chief Neil Gaughan and the telecommunications industry are talking about when it comes to data retention. Yet it’s these kinds of bureaucrats who are responsible for top-level oversight of the development of projects such as the data retention initiative. These departmental bureaucrats aren’t CIOs; and one has to suspect that even an experienced CIO would have trouble grappling with the technical issues inherent in this data retention disaster.

After I read through the documents which the Pirate Party’s Brendan Molloy had succeeded this week in dragging out of the Attorney-General’s Department, I also read this highly insightful piece by Crikey correspondent Bernard Keane. I recommend you do the same; in my analysis today, I drew mostly on the technical aspects of the documents, whereas Keane is more expert in the legal and regulatory implications.

But overall I think we both got the same feel from this highly confidential material. They paint a highly disturbing picture of a group of obscure bureaucrats working in complete secrecy, yet with the support of the highest levels of government (up to the office of the Prime Minister itself), to cast an incredibly massive net of surveillance over the entirety of Australian society; and doing so in an, at times, incredibly incompetent manner.

These are children attempting to play God with dangerous weapons they do not understand. Let us hope fervently that Parliament knocks back this dastardly proposal and that light continues to be shone in all the cracks in the Attorney-General’s Department. Because I’m sure that if a proposal like this existed for so long unknown, then there will be others still un-heard of.