As a consequence of my last post, I spent some time on the phone Friday with Andy Chou, Coverity’s CTO and former member of Dawson Engler’s research group at Stanford, from which Coverity spun off over a decade ago. Andy confirmed that Coverity does not spot the heartbleed flaw and said that it remained stubborn even when they tweaked various analysis settings. Basically, the control flow and data flow between the socket read() from which the bad data originates and the eventual bad memcpy() is just too complicated.

Let’s be clear: it is trivial to create a static analyzer that runs fast and flags heartbleed. I can accomplish this, for example, by flagging a taint error in every line of code that is analyzed. The task that is truly difficult is to create a static analysis tool that is performant and that has a high signal to noise ratio for a broad range of analyzed programs. This is the design point that Coverity is aiming for, and while it is an excellent tool there is obviously no general-purpose silver bullet: halting problem arguments guarantee the non-existence of static analysis tools that can reliably and automatically detect even simple kinds of bugs such as divide by zero. In practice, it’s not halting problem stuff that stops analyzers but rather code that has a lot of indirection and a lot of data-dependent control flow. If you want to make a program that is robustly resistant to static analysis, implement some kind of interpreter.

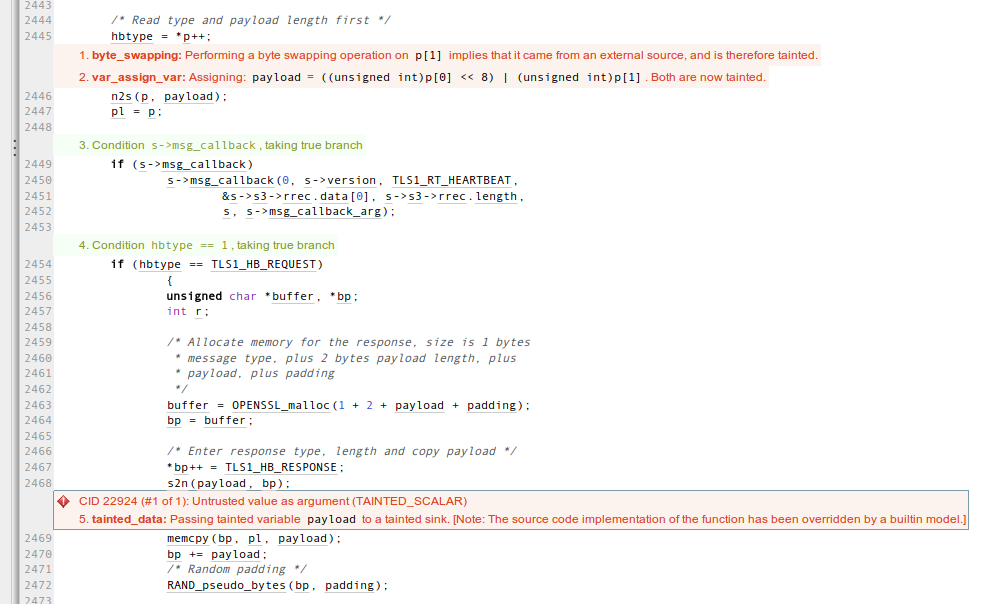

Anyhow, Andy did not call me to admit defeat. Rather, he wanted to show off a new analysis that he and his engineers prototyped over the last couple of days. Their insight is that we might want to consider byte-swap operations to be sources of tainted data. Why? Because there is usually no good reason to call ntohs() or a similar function on a data item unless it came from the network or from some other outside source. This is one of those ideas that is simple, sensible, and obvious — in retrospect. Analyzing a vulnerable OpenSSL using this new technique gives this result for the heartbleed code:

Nice! As you might guess, additional locations in OpenSSL are also flagged by this analysis, but it isn’t my place to share those here.

What issues are left? Well, for one thing it may not be trivial to reliably recognize byte-swapping code; for example, some people may use operations on a char array instead of shift-and-mask. A trickier issue is reliably determining when untrusted data items should be untainted: do they need to be tested against both a lower and upper bound, or just an upper bound? What if they are tested against a really large bound? Does every bit-masking operation untaint? Etc. The Coverity people will need to work out these and other issues, such as the effect of this analysis on the overall false alarm rate. In case this hasn’t been clear, the analysis that Andy showed me is a proof-of-concept prototype and he doesn’t know when it will make it into the production system.

UPDATE: Also see Andy’s post at the Coverity blog.