In April, federal authorities detected an ongoing remote attack targeting the United States’ Office of Personnel Management (OPM) computer systems. This situation may have gone on for months, possibly even longer, but the White House only made the discovery public last Friday. While the attack was eventually uncovered using the Department of Homeland Security’s (DHS) Einstein—the multibillion-dollar intrusion detection and prevention system that stands guard over much of the federal government’s Internet traffic—it managed to evade this detection entirely until another OPM breach spurred deeper examination.

While anonymous administration officials have blamed China for the attack (and many in the security community believe that the attack bears the hallmark of Chinese state-sponsored espionage), no direct evidence has been offered. The FBI blamed a previous breach at an OPM contractor on the Chinese, and security firm iSight Partners told The Washington Post that this latest attack was linked to the same group that breached health insurer Anthem.

OPM is the human resources department for the civilian agencies of the federal government, so this attack exposed records for over four million current and former government employees at places like the Department of Defense. The breach, which CNN dubbed “the biggest government hack ever,” included background and security clearance investigations on employees’ families, neighbors, and close associates stored in the Electronic Questionnaires for Investigations Processing (e-QIP) system and other databases. The attack also affected a data center operated by Department of the Interior used by OPM and other agencies as a shared service—the result of data center consolidation ordered by the Obama administration. As a result, even more agencies may have been directly affected.

The OPM hack is just the latest in a series of federal network intrusions and data breaches, including recent incidents at the Internal Revenue Service, the State Department, and even the White House. These attacks have occurred despite the $4.5 billion National Cybersecurity and Protection System (NCPS) program and its centerpiece capability, Einstein. Falling under the Department of Homeland Security’s watch, that system sits astride the government’s trusted Internet gateways. Einstein was originally based on deep packet inspection technology first deployed over a decade ago, and the system’s latest $218 million upgrade was supposed to make it capable of more active attack prevention. But the traffic flow analysis and signature detection capabilities of Einstein, drawn from both DHS traffic analysis and data shared by the National Security Agency, appears to be incapable of catching the sort of tactics that have become the modern baseline for state-sponsored network espionage and criminal attacks. Once such attacks are executed, they tend to look like normal network traffic.

Put simply, as new capabilities for Einstein are being rolled out, they’re not keeping pace with the types of threats now facing federal agencies. And with the data from OPM and other breaches, foreign intelligence services have a goldmine of information about federal employees at every level of the government. It’s a worrisome cache that could easily be leveraged for additional, highly-targeted cyber-attacks and other espionage. In a nation with a growing reputation for state of the art surveillance initiatives and cyber warfare techniques, how did we become the ones playing catch up?

Soft target

The Office of Personnel Management’s headquarters, the Theodore Roosevelt building in Washington, DC.

The Office of Personnel Management’s headquarters, the Theodore Roosevelt building in Washington, DC.

It’s no secret that information security at agencies like OPM needs to improve. OPM’s security practices were labelled as a “material weakness” by the OPM Inspector General’s (IG) office as far back as 2007. A November 2014 report upgraded the IG’s evaluation to merely a “significant deficiency,” but that was before a hack of contractor KeyPoint Government Solutions was discovered in 2014. The current OPM breached was discovered partially while following up on the KeyPoint situation.

Even before the KeyPoint attack, OPM was moving to correct its deficiencies. Until 2013, the agency had no internal IT staff with “professional IT security experience and certifications.” By November of 2014, seven such professionals had been hired and four more were in the pipeline. But only a fraction of the agency’s systems had been brought under the control of a central IT security organization.

The IG report noted that just 75 percent of OPM’s systems had valid authorizations to operate under Federal Information Security Managenent Act (FISMA) regulations. This was symptomatic of the way OPM handled its IT programs—a tangle of division-level projects with poor central oversight. Many of them were operated by agency contractors outside direct control of OPM’s IT staff. And as the IG report noted, “several information security agreements between OPM and contractor-operated information systems have expired.”

The mess continued. The IG noted that OPM wasn’t even sure of what it had on its network. “OPM does not maintain a comprehensive inventory of servers, databases, and network devices. In addition, we are unable to independently attest that OPM has a mature vulnerability scanning program.”

There was no multi-factor authentication for users accessing systems from outside OPM. So if someone’s credentials were stolen, an attacker could use them from outside to get access to just about anything. Even worse, OPM didn’t have control over how its systems were configured. An attacker could make software changes that fundamentally altered security. “OPM also has a software product that has the capability to detect, approve, and revert all changes made to information systems,” the IG team reported. “However, this capability has not been fully implemented, and OPM cannot ensure that all changes made to information systems have been properly documented and approved.”

The office of OPM’s chief information officer explained to IG inspectors that “configuration changes require approval by the Change Control Board which meets on a regular basis. However, there are emergency situations where changes might be made outside of the CCB cycle. [OPM] will ensure required documentation and approvals are in place for all configuration changes.” The recommendation for actual “technical controls” to prevent unapproved configuration changes wasn’t addressed.

Considering the overall condition of OPM’s security, it’s no surprise that an attacker—almost any attacker—could gain a foothold inside the agency’s network. But attackers didn’t just gain a foothold, they had practically a free run of the networks.

Uncovering the rot

In the wake of the KeyPoint hack and yet another scathing IG report, OPM got some outside help from the Department of Homeland security and other agencies in early 2015. And that’s when the trail left by OPM’s network intruders was first detected. According to DHS spokesman S.Y. Lee, DHS and “interagency partners” were helping the OPM improve its network monitoring “through which OPM detected new malicious activity affecting its information technology systems and data in April 2015.”

“Using these newly identified cyber indicators, DHS’s United States-Computer Emergency Readiness Team (US-CERT) used the [Einstein] system to discover a potential compromise of federal PII [personal identifying information],” Lee said.

DHS sent in incident response teams comprised of members of the US-CERT and other agencies “to identify the scope of the potential intrusion and mitigate any risks identified,” Lee said. “Based upon these response activities, DHS concluded at the beginning of May 2015 that OPM data had been compromised.”

That conclusion came after something found during the security assessment at OPM was added to Einstein. A signature for the suspicious behavior was configured in Einstein, which determined that the event wasn’t just historical—it was an ongoing breach of OPM’s systems and the Interior data center. After isolating the malware they believed to be the source of the attack, US-CERT’s team added a signature for that malware to Einstein’s filters so the system could watch for similar attacks on other federal networks.

DHS has since spread information to all federal chief information officers about the approach of this attack. The FBI has also been called in to investigate the situation as part of the inter-agency team. The FBI and US-CERT have even sent out an information bulletin on the attack to companies and other members of the information security community at large.

“DHS is continuing to monitor federal networks for any suspicious activity and is working aggressively with the affected agencies to conduct investigative analysis to assess the extent of this alleged intrusion,” Lee said.

It may be some time before the extent of the breach is known with any level of certainty. What is known is that a malware package—likely delivered via an e-mail “phishing” attack against OPM or Interior employees—managed to install itself within the OPM’s IT systems and establish a back-door for further attacks. The attackers then escalated their privileges on OPM’s systems to the point where they had access to a wide swath of the agency’s systems.

“This is the age-old approach to zero-day malware exploits,” said Ken Ammon, chief strategy officer at security firm Xceedium. “Once you have something running in your systems, if you don’t do something to prevent the attackers from escalating their rights, then that’s the keys to the kingdom.”

Given the apparent methods and duration of the attack, security experts Ars spoke with were confident it was carried out by a state-funded actor. “Since it’s been a long compromise, that makes me lean more toward it being a nation state compromise because the info hasn’t shown up anywhere,” said Grayson Milbourne, security intelligence director at Webroot. Most likely, the information was obtained for intelligence purposes—having security investigation data on key government employees could prove very useful for any foreign intelligence organization.

And that organization, by Ammon’s estimate, is probably located in China. “I have yet to see any exploit that has this level of sophistication and data targeting,” he said. “By sophistication, what I’m talking about is what you do to start getting the data out. Getting in is way too easy, but there’s nobody who’s had that level of sophistication for data exfiltration outside of Russia and China. Between the two, I’m placing my bets on the Chinese, because they have had a pretty consistent mission of gathering personal data. The raw data can be used in many ways, and none of them in our national interest.”

Unfortunately, many other small federal agencies may be just as vulnerable to attacks. Two decades of bad security practices, a long decline in internal information technology experience within civilian agencies, and a tendency to contract out critical parts of IT to private companies without a great deal of technical oversight have created ripe attack conditions. To boot, DHS’s efforts to provide a first line of defense against network attacks is based on an approach rooted in security strategies more than a decade old—and even that strategy is only now being fully put into place.

Einstein, cubed and accelerated

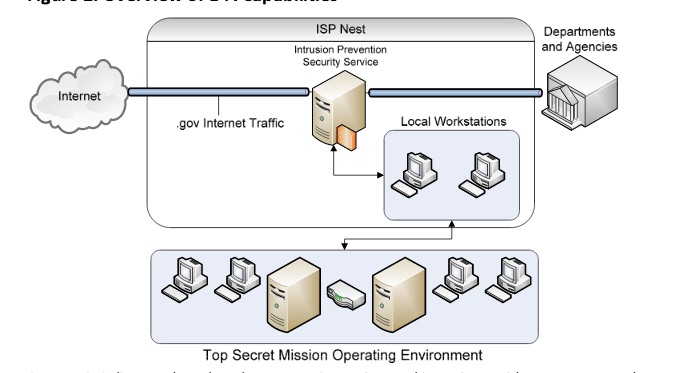

A DHS Inspector General report diagram of how Einstein works.

Einstein, despite its name, is not exactly an intelligent system. Much like NSA’s Xkeyscore surveillance system, it depends on its human DHS masters to tell it what exactly to look for.

Einstein began as strictly a network monitoring operation. In 2005, DHS’s National Protection Programs Directorate (NPPD) started putting the first generation of Einstein “sensors” on federal agencies’ Internet access points. Called Einstein 1, the system passively monitored .gov Internet traffic and collected “network flow records” in an attempt to establish baselines for normal network activity and detect potential attacks as they occurred.

DHS quickly discovered that agencies didn’t even know how many Internet gateways they had, let alone what was going out over their ISP connections. In 2007, Einstein 1 monitoring became a mandatory part of DHS’s Trusted Internet Connections initiative—an effort to pare down .gov networks’ Internet gateways to a manageable, securable number. In August of that year, NPPD debuted Einstein 2—a more advanced intrusion detection and alert capability. It was deployed with the ISPs serving as trusted Internet gateways to generate alerts on “the presence of malicious network activity,” according to a DHS Inspector General report. According to DHS officials, Einstein 2 is based exclusively on unclassified threat data—so it cannot be fed information from NSA.

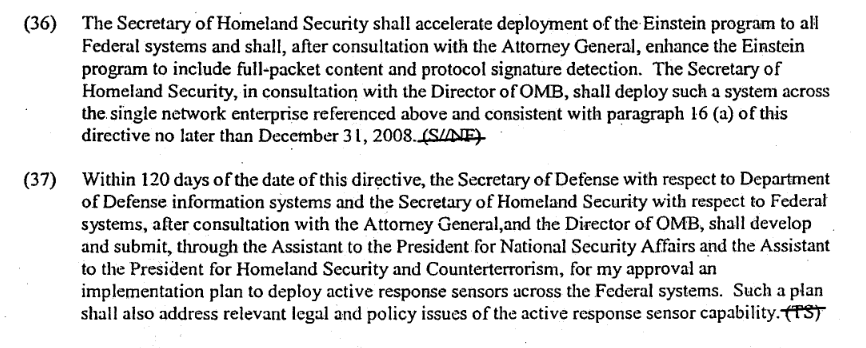

But the Bush administration’s cyber-strategists realized that intrusion detection wasn’t enough. A January 2008 secret directive, National Security Presidential Directive 54 (NSPD 54), mandated that federal agencies increase network protection. This launched the Comprehensive National Cybersecurity Initiative (CNCI)—an effort the Obama administration would quickly escalate to be the centerpiece of a larger national cybersecurity policy. One of the immediate requirements of CNCI was a government-wide intrusion prevention system. The feds wanted something that would shoot down cyber-attacks before they reached their networks.

The provisions of President George W. Bush’s NSPD-54 upping the ante on Einstein and calling for “active response sensors” to block and possibly counter network attacks.

The provisions of President George W. Bush’s NSPD-54 upping the ante on Einstein and calling for “active response sensors” to block and possibly counter network attacks.

That capability would become known as Einstein 3. “Einstein 3 will draw on commercial technology and specialized government technology to conduct real-time full packet inspection and threat-based decision-making on network traffic entering or leaving these Executive Branch networks,” members of the Obama Administration’s policy team wrote in a 2009 overview of CNCI’s action items. “The goal of Einstein 3 is to identify and characterize malicious network traffic to enhance cybersecurity analysis, situational awareness, and security response. It will have the ability to automatically detect and respond appropriately to cyber threats before harm is done, providing an intrusion prevention system supporting dynamic defense. EINSTEIN 3 will assist DHS US-CERT in defending, protecting and reducing vulnerabilities on Federal Executive Branch networks and systems.”

By April 2012, the “specialized government technology” part of the Einstein 3 equation was bogging things down. It became apparent that Einstein 3 wasn’t happening fast enough. DHS pivoted, reaching out to the industry for commercially available intrusion prevention tools under the program name “Einstein 3 Accelerated (E3A)” as a managed security service. The first service provider for E3A, Louisiana-based telecom company CenturyLink, got approved for operation and started in December 2014.

The main difference between Einstein 3’s vision and E3A’s delivered capability is that E3A still depends on identifying “known or suspected cyber-threats.” According to CenturyLink’s press release on the first E3A order, “EINSTEIN capabilities are provided through a combination of commercial off-the-shelf hardware and software, government-developed software, and commercially available managed security services that are enhanced by DHS-provided information.”

That “DHS-provided information” is threat profile information created by DHS’ US-CERT from analysis of existing attacks and threats. US-CERT and NPPD maintain local workstations at each trusted ISP running Einstein to pull recorded network traffic into DHS’ Top Secret Mission Operating Environment, a shared network that allows US-CERT analysts to dive into suspicious traffic and share it with NSA. However, that sharing occurs only after information has been appropriately scrubbed of personal identifying information, according to the privacy provisions of DHS policy. When threats are identified, the traffic data is used to create rules for the Einstein system’s sensors that will in turn trigger alerts and traffic blocking.

All that’s great for stopping attacks if they have been seen before. It’s not exactly great protection against “zero-day” attacks that disguise themselves as normal traffic. “Systems that are just based on detecting are a great compliment to other things,” said Ammon. “But if you’re betting the farm on that, it’s not a winning strategy. [On the other hand,] two years ago we wouldn’t have even known this was going on. That we can do something to get them out—that’s not something we could have done before.”

Defense out of its depth

Unfortunately, given the state of security at OPM and other federal agencies, this sort of post-attack forensics and remediation is about all Einstein will be good for in many cases. An Ars review of federal agency security audits found similar issues across the government with varying levels of severity. Even when security actions were taken, they were often misinformed—such as when the Economic Development Administration physically destroyed entire computers (including their keyboards and mice) when agency officials believed they were experiencing a malware outbreak in 2011.

Ammon believes the problems faced by the federal government are the same facing many organizations.

“What I see as the challenge here is that we spent 20 years accumulating a whole slew of bad practices, and we have issues with the underlying technology,” he said. “New technology really comes with the pricetag of changing how you do business—organizations used to have a basement with 100 really smart sysadmins, and nobody questioned how they did things.

“That sort of loosely controlled world is a playground for these attacks,” he continued. “So we have to overcome everything that we’ve accumulated from almost the advent of technology—this pile of bad practices and configurations—we have to unwind that and keep not only the hactivism guys out but well-funded state hackers out. It just takes time.”

It also will take a cultural change in government, and this problem isn’t only limited to federal government. State governments are an attractive target as well, especially to cyber-criminals looking to take advantage of antiquated tax systems and other setups laden with personal and financial data. State governments aren’t as well-equipped to deal with the mitigation of attacks. Webroot’s Milbourne noted that when he contacted State of Colorado’s Taxation Division about his tax return—which their system this past week still insisted the agency hadn’t received—he was told that because of a spike in fraud, all returns were being handled by hand. (Colorado’s Department of Revenue has not yet responded to an Ars inquiry on the issue.)

The most unnerving part of the current state of government IT security is that there’s no way to know the extent of breaches. The Obama administration doesn’t seem inclined to necessarily inform the public of them based on the comments Caitlin Hayden, a spokesperson who talked with the New York Times. “The administration has never advocated that all intrusions be made public. We have advocated that businesses that have suffered an intrusion notify customers if the intruder had access to consumers’ personal information. We have also advocated that companies and agencies voluntarily share information about intrusions.”

The security community is paying attention to both the breaches and bureaucratic banter. “They came off as belligerent, didn’t acknowledge their fault in the breach, and provided very few details,” Jeff Williams, CTO of Contrast Security, told Ars.. “How about the people whose sensitive information was in the e-QIP database, including me? What am I supposed to do now?”

Given the state of government IT, it’s a question many more American citizens may be asking in the near future.

Listing image: Disney / DHS

Sean was previously Ars Technica's IT and National Security Editor. After over 20 years in technology journalism, including over 9 at Ars, he pivoted to cybersecurity threat research, first at Sophos and now as a security research engineer at Cisco ‘s Talos Intelligence Group. A former Navy officer, he lives and works in Baltimore, Maryland.