How two Cosmonauts battled extreme cold, darkness, and limited resources to save Salyut 7.

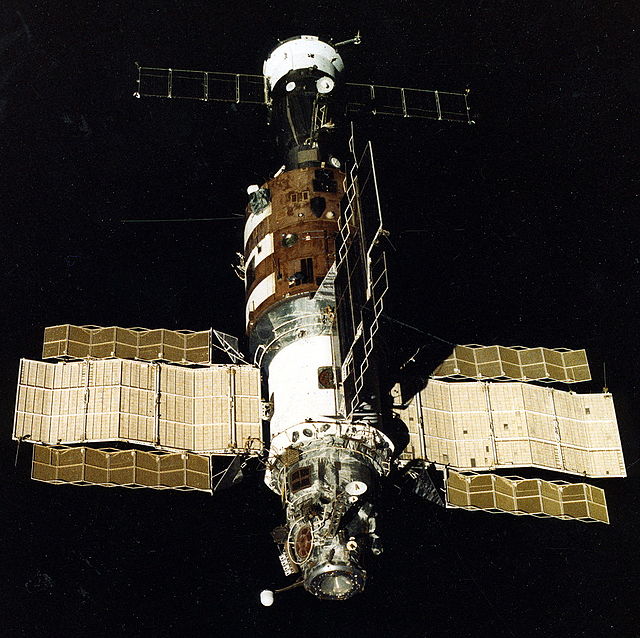

The view of Salyut 7 from Soyuz T-13 after undocking and beginning the journey home. Credit: spacefacts.de

The view of Salyut 7 from Soyuz T-13 after undocking and beginning the journey home. Credit: spacefacts.de

The following story happened in 1985 but subsequently vanished into obscurity. Over the years, many details have been twisted, others created. Even the original storytellers got some things just plain wrong. After extensive research, writer Nickolai Belakovski is able to present, for the first time to an English-speaking audience, the complete story of Soyuz T-13’s mission to save Salyut 7, a fascinating piece of in-space repair history.

It’s getting dark, and Vladimir Dzhanibekov is cold. He has a flashlight, but no gloves. Gloves make it difficult to work, and he needs to work quickly. His hands are freezing, but it doesn’t matter. His crew’s water supplies are limited, and if they don’t fix the station in time to thaw out its water supply, they’ll have to abandon it and go home, but the station is too important to let that happen. Quickly, the sun sets. Working with the flashlight by himself is cumbersome, so Dzhanibekov returns to the ship that brought them to the station to warm up and wait for the station to complete its pass around the night side of the Earth. [1]

He’s trying to rescue Salyut 7, the latest in a series of troubled yet increasingly successful Soviet space stations. Its predecessor, Salyut 6, finally returned the title of longest manned space mission to the Soviets, breaking the 84-day record set by Americans on Skylab in 1974 by 10 days. A later mission extended that record to 185 days. After Salyut 7’s launch into orbit in April 1982, the first mission to the new station further extended that record to 211 days. The station was enjoying a relatively trouble-free start to life. [4]

However, this was not to last. On February 11, 1985, while Salyut 7 was in orbit on autopilot awaiting its next crew, mission control (TsUP) noticed something was off. Station telemetry reported that there had been a surge of current in the electrical system, which led to the tripping of overcurrent protection and the shutdown of the primary radio transmitter circuits. The backup radio transmitters had been automatically activated, and as such there was no immediate threat to the station. Mission controllers, very tired now that the end of their 24-hour shift was approaching, made a note to call specialists from the design bureaus for the radio and electrical systems. The specialists would analyze the situation, and produce a report and recommendation, but for now the station was fine, and the next shift was ready to come on duty.[9]

Without waiting for the specialists to arrive, or perhaps not bothering to call them in the first place, the controllers on the next shift decided to reactivate the primary radio transmitter. Perhaps the overcurrent protection had been tripped accidentally, and if not, then it should still be functional and should still activate if there really was a problem. The controllers, acting against established tradition and procedures of their office, sent the command to reactivate the primary radio transmitter. Instantly, a cascade of electrical shorts swept through the station, and knocked out not only the radio transmitters, but also the receivers. At 1:20pm and 51 seconds on February 11, 1985, Salyut 7 fell silent and unresponsive. [8][9]

What do we do now?

The situation put flight controllers in an uncomfortable position. One option available to them was to simply abandon Salyut 7 and wait for its successor, Mir, to become available before continuing the manned space program. Mir was on schedule to be launched within one year, but waiting for Mir to become available would not only mean suspending the space program for a year; it also meant that a significant amount of scientific work and engineering tests planned for Salyut 7 would have to go undone. Moreover, admitting defeat would be an embarrassment for the Soviet space program, particularly painful considering the multitude of previous failures in the Salyut series as well as the apparent successes the Americans were enjoying with the Space Shuttle. [9]

There was only one other option: fly a repair crew to the station to fix it from the inside, manually. But this could easily become yet another failure. The standard procedures for docking to a space station were entirely automated and relied heavily on information from the station itself about its precise orbital and spatial coordinates. During those rare occurrences when the automated system failed and a manual approach was required, the failures were all within several hundred meters of the station. How does one approach a silent space station? [9] The lack of communication presented another problem: there was no way to know the status of the onboard systems. While the station was designed to fly autonomously, the automated systems could only cope with so many failures before human intervention would be required. The station could be fine upon the repair crew’s arrival, requiring no more repair work than replacing the damaged transmitters, or there could have been a fire on the station, or it could have depressurized from having been struck by space debris, etc.; there would be no way to know.[3]

If there was a meeting in which top managers discussed and weighed all the options, the notes of that meeting have not been made public. What *is* known, however, is that the Soviets decided to attempt a repair mission. This would mean rewriting the book on docking procedures from scratch and hoping that nothing else went wrong aboard the station while communication was down, because if something else did go wrong, the repair crew might not be able to handle it. It was a bold move.

“Docking with a non-cooperative object”

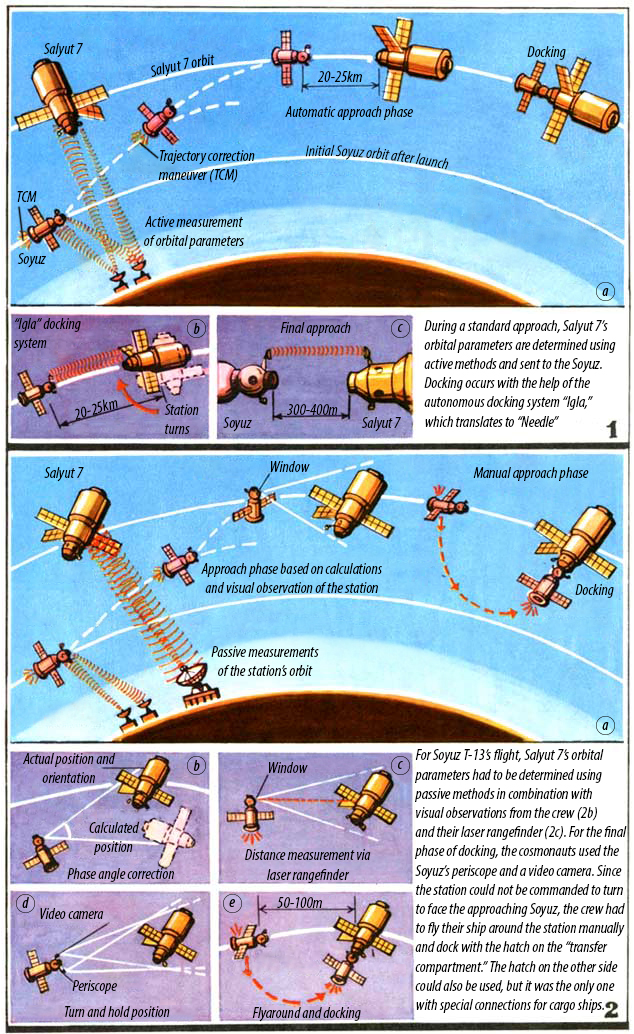

The first order of business for the repair mission was figuring out how they would get to the station. For an approach to the station under better circumstances, the Soyuz (a 3-seat ship used to ferry cosmonauts to and from space stations) would receive information from the station via mission control (TsUP) as soon as it reached orbit, long before the station would be visible to the crew. This communication would contain information about the orbit of the space station so that the visiting craft could plot a rendezvous orbit. Once the two craft were 20-25km apart, a direct line of communication would be established between the station and the ship, and the automated system would bring the two craft together and complete the docking.[3]

Part 1: A depiction of a typical Soyuz rendezvous and docking. Part 2: A depiction of the modified rendezvous and docking procedure employed for Soyuz T-13. Notice how in parts 2b and 2c the ship is actually flying sideways. Credit: epizodsspace.noip.org (translated by the author)

Although all Soyuz pilots were trained to perform a manual docking, it was rare for the automated system to fail. Of those rare failures, the worst was in June 1982 on Soyuz T-6 when a computer failure stopped the automated docking process 900m away from the station. Vladimir Dzhanibekov immediately took over controls and successfully docked his Soyuz with Salyut 7 a full 14 minutes ahead of schedule [4]. Naturally, Dzhanibekov was the leading candidate to pilot any proposed mission to rescue Salyut 7.

An entirely new set of docking techniques had to be developed, and this was done under a project titled “docking with a non-cooperative object.” [5] The station’s orbit would be measured using ground-based radar, and this information would be communicated to the Soyuz, which would then plot a rendezvous course. The goal was to get the ship within 5km of the station, from which point it was deemed a manual docking was technically possible. [3] The conclusion of those responsible for developing these new techniques were that the odds of mission success were 70 to 80 percent, after proper modifications to the Soyuz. [2],[3] The Soviet government accepted the risk, deeming the station too valuable to simply let it fall from orbit uncontrolled.

Modifications to the Soyuz began. The automated docking system would be removed entirely, and a laser rangefinder installed in the cockpit to assist the crew in determining their distance and approach rate. The crew would also bring night vision goggles in case they had to dock with the station on the night side. The third seat of the ship was removed, and extra supplies, like food and, as would later prove critical, water, were brought on board. The weight saved by the removal of the automatic system and the third chair were used to fill the propellant tanks to their maximum possible level. [1],[3],[11]

Who would fly the mission?

When it came to selecting a flight crew, two things were very important. First of all, the pilot should have had experience performing a manual docking in orbit, not just in simulators, and secondly, the flight engineer would need to be very familiar with Salyut 7’s systems. Only three cosmonauts had completed a manual docking in orbit. Leonid Kizim, Yuri Malyshev, and Vladimir Dzhanibekov. Kizim had only recently returned from a long duration mission to Salyut 7, and was still undergoing rehabilitation from his spaceflight, which ruled him out as a possible candidate. Malyshev had limited spaceflight experience, and had not trained for Extra-Vehicular Activity (EVA, or spacewalk), which would be required later in the mission to augment the station’s solar panels, provided the rehabilitation of the space station went well.[1]

This left Dzhanibekov, who had flown in space four times for a week or two each time, but had trained for long duration missions and for EVA. However, he was restricted from long duration flight by the medical community. Being at the top of the short list for mission commander, Dzhanibekov was quickly placed into the care of physicians who, after several weeks of medical tests and evaluation, cleared him for a flight lasting no more than 100 days. [1]

To fulfill the role of flight engineer the list was even shorter: just one person. Victor Savinikh had flown once before, on a 74 day mission to Salyut 6. During that mission he played host to Dzhanibekov and Mongolia’s first cosmonaut as they visited the station on Soyuz 39. Moreover, he was already in the process of training for the next long-duration mission to Salyut 7, which had been scheduled to launch on May 15, 1985. [1]

By the middle of March, the crew had been firmly decided. Vladimir Dzhanibekov and Victor Savinikh were chosen to attempt one of the boldest, most complicated in-space repair efforts to date. [1]

Po’yehali! Let’s go!

Salyut 7 as seen from the approaching Soyuz T-13 crew. Notice how the solar panels are slightly askew. Credit: Wikimedia

On June 6, 1985, nearly four months after contact with the station had been lost, Soyuz T-13 launched with Vladimir Dzhanibekov as commander and Victor Savinikh as flight engineer. [1],[6] After two days of flight, the station came into view.

As they approached the station, live video from their ship was being transmitted to ground controllers. To the right is one of the images controllers saw.

The controllers noticed something very wrong: the station’s solar arrays weren’t parallel. This indicated a serious failure in the system which orients the solar panels toward the sun, and immediately led to concerns about the entire electrical system of the station. [1]

The crew continued their approach.

Dzhanibekov: “Distance, 200 meters. Engaging engines. Approaching the station at 1.5 m/s, rotational speed of the station is normal, it’s practically stable. We’re holding, and beginning our turn. Oh, the sun is in a bad spot now… there, that’s better. Docking targets aligned. Offset between the ship and the station within normal parameters. Slowing down… waiting for contact.”

Silently, slowly, the crew’s Soyuz flew toward the forward docking port of the station.

Savinikh: “We have contact. We have mechanical capture.”

The successful docking to the station was a great victory, and demonstrated for the first time in history that it was possible to rendezvous and dock with virtually any object in space, but it was early to celebrate. The crew received no acknowledgement, either electrical or physical, from the station of their docking. One of the main fears about the mission, that something else would go seriously wrong while the station was out of contact, was quickly becoming a reality.

A lack of information on the crew’s screens about the pressure inside the station led to concerns that the station had de-pressurized, but the crew pressed ahead, carefully. Their first step would be to try to equalize the pressure between the ship and the station, if possible. [1][3]

Like being in an old abandoned home

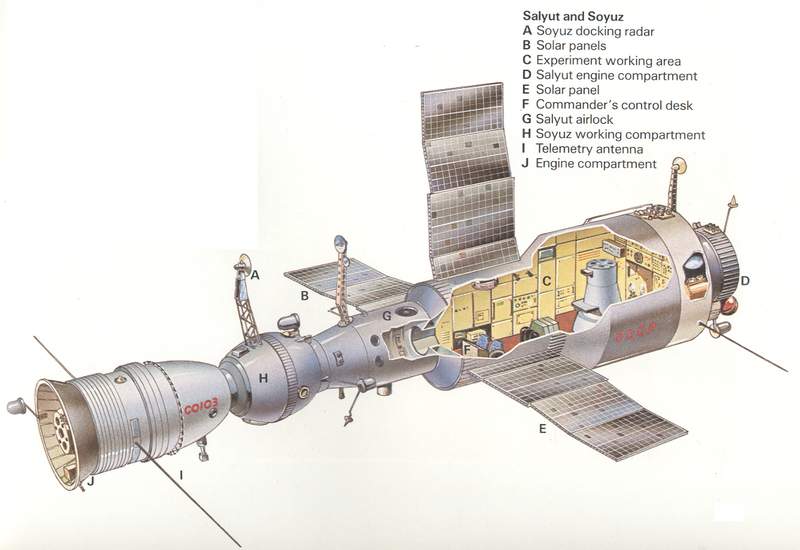

Starting with Salyut 6, all Soviet/Russian stations had at least two docking ports, a forward port that connected to the station’s airlock and an aft port that connected to the station’s main section. The aft port also had connections that led to the station’s propellant tanks so they could be refilled by visiting cargo spacecraft called “Progress.” The crew had docked to the forward port, and so began equalizing pressure there. The diagram below shows the layout of Salyut 4, which was similar in design and construction to Salyut 7.

A Soyuz ship (left) is docked with Salyut 4. The ship is docked to the station’s airlock, section G, which has hatches connecting it to section H on the Soyuz and section C on the station. Starting with Salyut 6, section D was redesigned to house a docking port as well as an engine compartment. Soyuz ships can dock to either port, but Progress ships can only dock to the aft port.

A Soyuz ship (left) is docked with Salyut 4. The ship is docked to the station’s airlock, section G, which has hatches connecting it to section H on the Soyuz and section C on the station. Starting with Salyut 6, section D was redesigned to house a docking port as well as an engine compartment. Soyuz ships can dock to either port, but Progress ships can only dock to the aft port. Credit: spacecollection.info

The crew would have to go through a total of three hatches before getting to the main section of the station known as the “work compartment.” First they would open the ship-side hatch, and open a small porthole on the station side hatch to equalize pressure between their ship and the station’s airlock. Once that was done and they had entered and inspected the airlock, they would be able to begin working on the hatch between the airlock and the work compartment

Earth: “Open the [ship-side] hatch.”

Savinikh: “We got it open.”

Earth: “Was it tough? What’s the temperature of the [station-side] hatch?”

Dzhanibekov: “The [station-side] hatch is sweaty [from condensation], we can’t see anything else.”

Earth: “Copy that. Carefully rotate the cap* 1-2 turns and then quickly move back into the habitation module. Be prepared to close the ship-side hatch. Volodya [Dzhanibekov], you open it just one turn and listen if it’s hissing or not.”

Dzhanibekov: “Got it. It’s hissing a little, not too strongly.”

Earth: “Well open it a little bit more then.”

Dzhanibekov: “Done. It’s really hissing, the pressure is equalizing.”

Earth: “Close the [ship-side] hatch.”

Savinikh: “[ship-side] hatch closed.”

Earth: “Let’s wait and see for say, three minutes, and then we’ll move forward”

Dzhanibekov: “No change in pressure… it’s starting to equalize. Really really slowly.”

Earth: “Well, we still have a long flight ahead of us. And so no reason to rush!”

Dzhanibekov: “Pressure is at 700mm. The drop was about 20-25mm. We’ll open the [ship-side] hatch now. Open.”

Earth: “Jiggle the cap.”

Dzhanibekov: “Hold on.”

Earth: “Is the cap hissing? Jiggle it. Maybe it’s got a bit more to go, and you can keep equalizing the pressure with it.”

Dzhanibekov: “Faster, yea?”

Earth: “Of course.”

Dzhanibekov: “We’ll figure this problem out quickly. Ah, that familiar smell of home… OK I’m opening the cap even more. There, now we’re talking.”

Earth: “It’s hissing?”

Dzhanibekov: “Yes. Pressure 714mm.”

Earth: “Is there a cross-flow?”

Dzhanibekov: “Yes.”

Earth: “If you’re ready to open the station-side hatch, you can go ahead.”

Dzhanibekov: “We’re ready, opening the hatch. Op-a, it’s open.”

Earth: “What do you see?”

Dzhanibekov: “No, I mean I’ve got the lock open. Now I’m trying to open the hatch. Entering.”

Earth: “First impressions? What’s the temperature like?”

Dzhanibekov: “Kolotun*, brothers!”

At this point the cosmonauts started to grasp their predicament. The station’s electrical system was out of power, and thermal control systems had been shut down for some time. This meant that not only were critical provisions like water frozen, all of the station’s systems had been exposed to temperatures they were never designed to operate under. It wasn’t even really clear if it was safe for the crew to be onboard.

Earth: “It is really cold?”

Dzhanibekov: “Yes.”

Earth: “Well then you should close the hatch to the habitation module a little bit, not all the way.”

Dzhanibekov: “No unusual smells, cold though.”

Earth: “You should take the covers off the portholes.”

Dzhanibekov: “We’re taking them off as we go.”

Earth: “On the hatch you just opened, you need to close the cap all the way.”

Dzhanibekov: “We’ll do it immediately.”

Earth: “Volodya, what do you think, is it minus or plus[centigrade]?”

Dzhanibekov: “Plus, just a little. Maybe +5.”

Earth: “Try turning on the light.”

Savinikh: “We’re trying to turn on the light now. Command issued. No reaction, not even one little diode. If only something would light up…”

Earth: “If it’s cold, dress up… take your time to get acclimated and slowly get to work. And everybody needs to eat. Congratulations on entering!”

Dzhanibekov: “Thanks.”

Shortly thereafter, their orbit took them out of range of ground stations and therefore out of contact with mission control. This was a normal occurrence back then; today relay satellites in high altitude orbits ensure constant communication with the International Space Station (ISS). Later in the day, the crew re-established communication with mission control as they prepared to analyze the air inside the work compartment by allowing some of it into indicator tubes. These tubes would indicate the presence of ammonia, carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide, or other gases that might indicate that there had been a fire aboard the station, or something like that.

Earth: “What’s the temperature like?”

Savinikh: “3-4 degrees. Nice and chilly.”

Earth: “What’s the pressure in the compartment?”

Savinikh: “693 mm. Commencing gas analysis.”

Earth: “Please, when you’re performing the analysis, hold the indicators in your hand for a little bit to warm them up. It’ll increase their accuracy. Are you guys working with flashlights?”

Savinikh: “No we opened all the portholes, it’s sunny here. At night we work with flashlights.” [In a typical Low Earth Orbit the spacecraft will circumnavigate the Earth once every 90 minutes, so day and night each last 45 minutes.]

Earth: “We’re planning to open the hatch [to the work section] on the next orbit. And on that I think we’ll end for the day. You guys are tired enough. We’ll pick up in the morning.”

Savinikh: “Understood.”

The indicator tubes indicated the atmosphere on the station was normal, so the crew equalized the pressure between the compartments in a similar manner to what they had done before with the outside hatch of the airlock. Mission control advised them to put on their gas masks, just in case, and open the hatch.

They floated in with their flashlights and their winter coats, and found the station cold and dark, with frost along the walls. Savinikh tried to turn the lights on—nothing, not that he expected anything. They took off their gas masks—they were making it even more difficult to see around the darkened station, and there was no smell of fire. Savinikh dived to the floor and opened the shade covering a window. A ray of sunlight fell on the ceiling, illuminating the station a little bit. They found the crackers and salt tablets that were left on the table by the previous crew—part of a traditional Russian welcoming ceremony that is still performed on the ISS today—as well as all the onboard station documentation neatly packed and secured to its shelves. All of the ventilators and other systems that normally hummed noisily were off. Savinikh recalls in his flight journal “it felt like being in an old, abandoned home. There was a deafening silence pressing upon our ears.” [1]

Now that the crew and mission control were aware of their predicament, they had to do something about it. The crew woke the next morning to instructions from the ground: first examine “Rodnik,” the potable water storage system, and see if the water there was frozen. They were also given limitations on their ability to work. Due to the lack of ventilation in the frozen station, a cosmonaut’s exhalations would build up around him, and he could easily succumb to carbon dioxide poisoning. Therefore the ground limited the crew to working in the station one at a time, with the one in the ship keeping an eye on the one in the station for signs of CO2 poisoning. Dzhanibekov went first.

Earth: “Volodya, if you spit, will it freeze?”

Dzhanibekov: “I’m trying it now. I spit, and it froze. In three seconds.”

Earth: “Did you spit right on the window, or where?”

Dzhanibekov: “No, on the insulation. The rubber here is frozen. It’s like a rock.”

Earth: “That doesn’t make us feel any better.”

Dzhanibekov: “Us neither.”

Later, Savinikh took his place, and tried to pump air either in or out of the air bladders of the system.

Savinikh: “I’ve gotten the Rodnik schematics. Pump connected. The valves aren’t opening. There’s an icicle sticking out of the air pipe.”

Earth: “Understood, let’s put Rodnik aside for now. We’ll run to the other side. We need to know, how many “live” battery blocks there are that we can reanimate. We’re working on a procedure to connect the station’s solar panels directly to the blocks.”

The problem with Rodnik was serious. The crew had water reserves for eight days in total, enough to last until June 14. It was already flight day 3—if they rationed their water use down to a minimum, tapped into the Soyuz’s emergency water supply, and managed to heat up a couple water packets that were on the station, they could stretch their supplies until June 21, giving themselves not more than 12 days to repair the station. [1]

Dzhanibekov works in the cold to repair Salyut 7 Credit: epizodsspace.airbase.ru

The station’s batteries were normally charged by an automated system, which itself needed electricity in order to function. Somehow, the crew needed to get electricity into the batteries. The easiest way to recharge them would have been to transfer power from the Soyuz’s batteries, but it was still unclear what the status of the station’s electrical system was. If there was still an electrical short somewhere in the station’s systems, it could knock out the Soyuz’s electrical system as well, and the cosmonauts would be stranded. [1]

Instead, ground controllers came up with a complex procedure for the crew to implement. Firstly, they would test the station’s batteries to see how many of them could accept a charge. Much to their happiness, six of the eight batteries were deemed salvageable. Next, the crew prepared cables to connect the batteries directly to the solar panels. All told, they had to put together 16 cables, connecting the leads of the cables by their bare hands in the cold of the station. With the cables connected, the crew would clamber into the Soyuz and use its attitude control engines to re-orient the station so that its solar panels would face sunlight.

Earth: “We’re going to go a turn around the Y-axis using the control system of Soyuz T-13 to light up the solar panels. Before our next communications session, we need you to connect the positive leads to all the good battery blocks. Then we’ll complete the re-orientation and start charging the first block.”

Dzhanibekov: “We’re going to do this manually?”

Earth: “Yes, manually.”

Savinikh: “OK.”

Dzhanibekov: “I’m ready.”

Earth: “Turn along the pitch axis until the sun comes into view. As soon as that happens, start braking the rotation.”

Dzhanibekov: “OK. Handle is down. Pitching.”

Earth: “Have you started braking yet?”

Dzhanibekov: “Not yet.”

Earth: “The air also concerns us. We need to organize a duct in the work section.”

Dzhanibekov: “Understood. We only have one regenerator [CO2 scrubber]: that’s why the readings take so long to get to the desired level.”

Earth: “We’ll think about it: maybe install a second regenerator.”

Dzhanibekov: “We have enough cables for that…. the sun is centered in my visual field…turning clockwise.”

Savinikh: “It’s like in good winter weather. There’s snow on the windows and the sun is shining!”

Earth: “We consider the charging to have begun.”

Dzhanibekov: “Thank God!”

Earth: “Not understood. We didn’t hear you.”

Dzhanibekov and Savinikh together: “Thank God!”

Earth: “Great work.”

Savinikh notes in his flight journal, “that day was the first happy spark of hope in that mountain of problems, unknowns, and hardships that Volodya and I were faced with solving”

All the while they had been working, they really didn’t know if they would be staying, or if they would run out of water first. They tried not to talk about it, focusing instead on their work. After having re-orientated the station and waiting for about a day, five batteries had been charged.

The crew disconnected them from their rudimentary charging system, and connected them to the station’s electrical grid. They turned on the lights, and much to their relief, the lights came on.

Over the next few days, they set about re-initializing various systems on board the station. They turned on the ventilation and air regenerators so that they could both work on the station at the same time. There was so much to do, that they spent the entire day in the station, coming back to the Soyuz to sleep happy and “wonderfully frozen.” [1]

On June 12, flight day 6, the crew began replacing the fried communications system and testing the water coming out of the slowly-thawing Rodnik system for contaminants.

On June 13, flight day 7, the crew continued their work with the communications system, and by afternoon Moscow time, ground control had re-established a link with the station. They also tested the automatic docking system, knowing that if the test failed they would have to go home. The station needed supplies, and they could only be brought in large enough quantities by cargo ships which could not be controlled manually like the Soyuz. But thankfully, the test was successful, and the cosmonauts continued their mission.

Finally, on June 16—flight day 10 and two days after water supplies were initially supposed to run out—“Rodnik” was fully operational. There were finally enough working systems and enough supplies to continue the mission. [1]

Dzhanibekov and Savinikh report from a recently-revived Salyut 7. Credit: epizodsspace.airbase.ru

The rest of the story

A single faulty sensor was determined to be the cause of the station’s descent into a frozen darkness. It was a sensor which monitored the state of charge of battery number four. The sensor was designed to shut down the charging system when the battery to which it was connected was full, in order to prevent overcharging that battery. Each of the seven primary batteries and the single backup battery had such a sensor and any one of the sensors – primary or backup – had the authority to shut down the charging system. [3]

At some point after the loss of communication with the station, battery four’s sensor developed a problem. It began to report the battery as full even when it wasn’t. Every time the on-board computer sent a command to charge the batteries, which happened once a day, battery four’s sensor would immediately cancel the charge. Eventually on-board systems drained the batteries completely, and the station slowly began to freeze. Had communication with the station been available, controllers could have intervened and overridden the faulty sensor. Without communication, it was impossible to tell exactly when the sensor had failed. [3],[12]

Dzhanibekov stayed on the station for a total of 110 days. He returned home on Soyuz T-13 with Georgi Grechko, who had flown up to the station with Vladimir Vasyutin and Alexander Volkov on Soyuz T-14 in September of 1985. Vasyutin, Volvkov, and Savinikh remained on board for a long term expedition which was cut short in November as Vasyutin fell ill, forcing an emergency return to Earth.

On February 19, 1986, the core block of Salyut 7’s successor station, Mir, was launched. Although its replacement was in orbit, Salyut 7’s role in the Soviet space station program was not quite finished. The first crew to launch to Mir did something unprecedented. After arriving at Mir and performing initial operations to bring the new station online, they boarded their Soyuz and flew to Salyut 7, the first and, to date, only time in history a station-to-station crew transfer had taken place. They completed the work left behind by the Soyuz T-14 crew, after which they returned to Mir before eventually returning to Earth.

The Soviets hoped to continue using Salyut 7 even after Soyuz T-15 had departed, and so the station was placed into a high altitude storage orbit. However, with the collapse of the Soviet Union and the Russian economy, funding for future missions to Salyut 7, either with Soyuz ships or the then-in-development Buran shuttle, never materialized, and the station’s orbit slowly degraded until it underwent an uncontrolled re-entry over South America in 1991. [7]

Although the station itself is gone, its legacy of triumph over adversity remains. Salyut 7 experienced some of the most serious problems of any station in the Salyut series, but while earlier stations were lost, the skill and determination of the designers, engineers, ground controllers, and cosmonauts of Salyut 7 kept the station flying. That spirit lives on today in the International Space Station, which has flown continuously for over 15 years. It too experiences systems failures, coolant leaks, other problems, but like their predecessors who worked on Salyut 7, the designers, engineers, ground controllers, cosmonauts, and astronauts exhibit that same determination to keep flying.

Nickolai Belakovski is an engineer with a background in aerospace engineering. He is fluent in English and Russian and gathered a number of technical and non-technical sources in order to understand what really happened in the leadup to and execution of the Soyuz T-13 mission. His bibliography is included below.

- Savinikh, Victor. “Notes from a Dead Station.” Publishing House of the Alice System. 1999. Web. <http://militera.lib.ru/explo/savinyh_vp/index.html> *

- Gudilin, V. E., Slabkiy, L. I. “Rocket-space systems.” Moscow, 1996. Web. <http://www.buran.ru/htm/gudilin2.htm> *

- Blagov, Victor. “Technical abilities, mastery, and the courage of people.” Science and Life, 1985, volume 11: pages 33-40. Web. <http://epizodsspace.no-ip.org/bibl/n_i_j/1985/11/letopis.html> *

- Portree, David S. F. Mir hardware heritage. Washington, DC: National Aeronautics and Space Administration, 1995. Print. Web. <http://ston.jsc.nasa.gov/collections/TRS/_techrep/RP1357.pdf>

- Glazkov, Yu. N., Evich, A. F. “Repair on Orbit.” Science in the USSR, 1986, volume 4. Web. <http://epizodsspace.no-ip.org/bibl/nauka-v-ussr/1986/remont.html> *

- “Soyuz T-13.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, 21 Apr. 2014. Web. <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Soyuz_T-13>.

- Mcquiston, John. “Salyut 7, Soviet Station in Space, Falls to Earth After 9-Year Orbit.” The New York Times. The New York Times, 6 Feb. 1991. Web. <http://www.nytimes.com/1991/02/07/world/salyut-7-soviet-station-in-space-falls-to-earth-after-9-year-orbit.html>

- Kostin, Anatoly. “The Ergonomic Story of the Rescue of Salyut 7.” Ergonomist, February 2013, volume 27: pages 18-22. Web. 26 May 2014. <http://www.ergo-org.ru/newsletters.html> *

- Chertok, B. E. “People in the Control Loop.” Rockets and People. Washington, DC: NASA, 2011. 513-19. Web. 09 Aug 2014. <http://www.nasa.gov/connect/ebooks/rockets_people_vol4_detail.html> [English], <http://militera.lib.ru/explo/chertok_be/index.html> [Russian]

- Nesterova, V., O. Leonova, and O. Borisenko. “In Contact — Earth.” Around the World, October 197, volume 2565: issue 10 Web. 9 Aug. 2014. <http://www.vokrugsveta.ru/vs/article/3714/>.*

- Canby, Thomas Y. “Are the Soviets Ahead in Space?” National Geographic 170.4 (1986): 420-59. Print.

- Savinikh, Victor. “Vyatka Baikonur Space.” Moscow: MIIGAAiK. 2002. Web. <http://epizodsspace.airbase.ru/bibl/savinyh/v-b-k/obl.html>>*