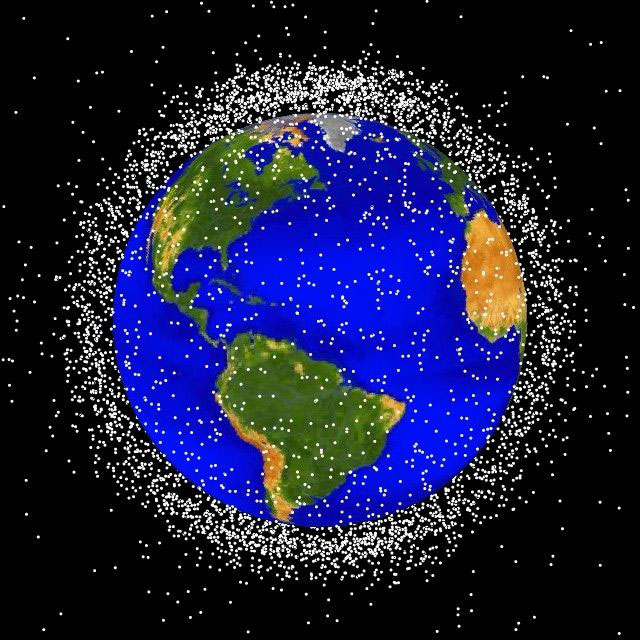

As Gravity made clear to the general public, it’s getting crowded in Earth orbit. In the nearly 57 years since Sputnik’s launch on October 4, 1957, Earth has seen a cloud of human-created objects continue to grow, expanding like dandelion fluff around our planet. In 2014, there’s good and bad news on the subject.

Some good news is that Gravity’s makers seized on a plausible scientific disaster scenario—the Kessler syndrome, an expanding cascade of space debris—and amped the volume up to 11 for dramatic purposes. The filmmakers kept only as much science as they felt like keeping, as movie-makers have done before. (The China Syndrome did it with nuclear meltdowns in 1979, for instance.) The actual science detailing how a Kessler-type situation would unfold presents a more nuanced picture than Gravity.

The bad news is that the Kessler syndrome isn’t merely some science-fictional theory hyped by Gravity. In a true case of Kessler syndrome, the density of orbital objects becomes so great that collisional cascading is triggered, and one initial collision generates ever more smash-ups among ever greater quantities of space junk. We’ve already reached the point where the growth of debris in low Earth orbit (LEO) has become self-sustaining. Human access to space might eventually become impossible.

“The Kessler Syndrome is a mathematical singularity,” said Darren McKnight, a member of a recent National Academies panel on NASA’s meteoroid and orbital debris program. “Based on the equations, we’ve already passed the critical density.”

Recent real-world events support McKnight’s evaluation. In January 2007, a Chinese “hit-to-kill” ASAT (anti-satellite) demo generated more than 2,317 trackable items of debris as well as an estimated 150,000 untrackable pieces 1 cm or larger and one million pieces 1 mm or larger. In February 2008, the US shot down a dying satellite for purported safety reasons. One year later, the first accidental hypervelocity collision between two satellites—a dead Russian Cosmos satellite and a functioning US Iridium—occurred. And in 2011, the US National Academy of Sciences stated that orbital junk in two bands of LEO space—the 900 to 1,000km (620 miles) and 1,500km (930 miles) altitudes—already exceeded the necessary density.

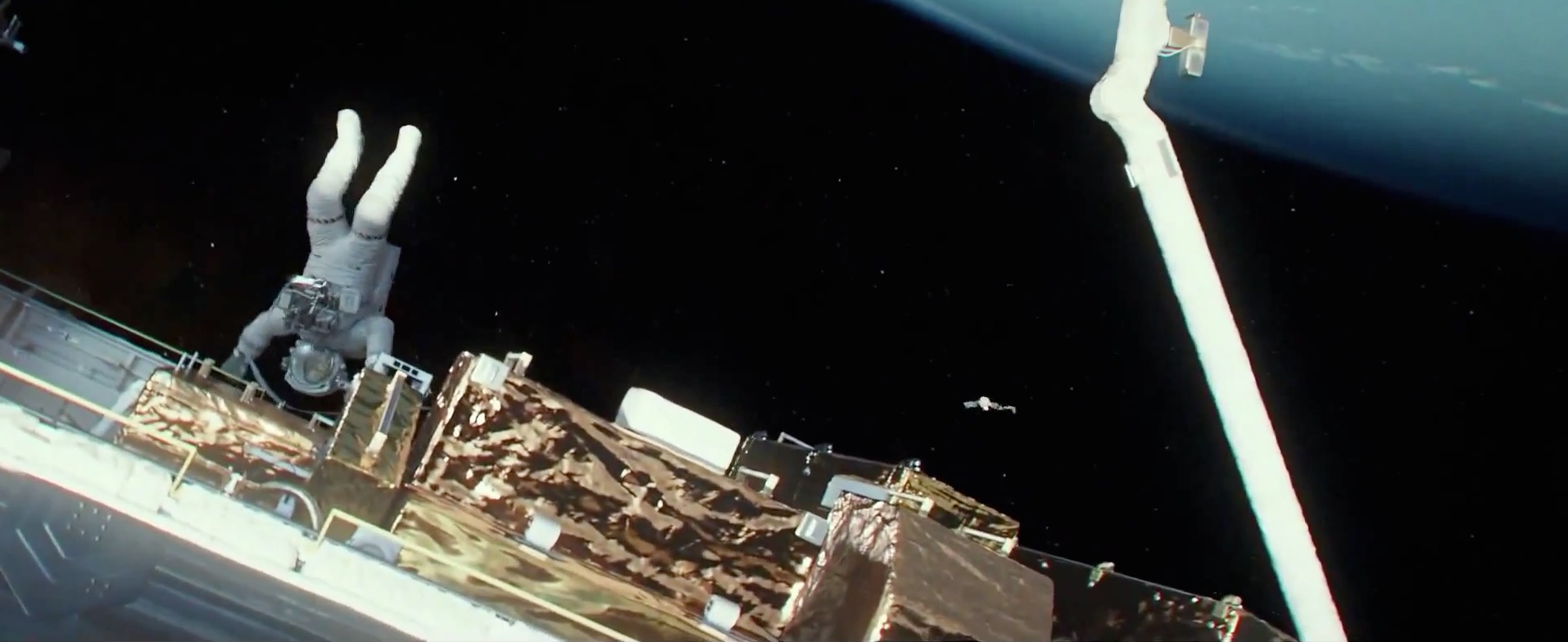

Screencap from the Gravity trailer, showing the start of a giant debris storm. Note the monstrous size of the piece of debris near frame center.

Credit: Warner Bros

Screencap from the Gravity trailer, showing the start of a giant debris storm. Note the monstrous size of the piece of debris near frame center. Credit: Warner Bros

Force before facts

Again, there’s good news. Active debris removal is technically challenging, but potential solutions exist. Things like “laser brooms,” electrodynamic tethers, nanosatellites, solar sails, space grapples, and tugs are being considered (more on these to come). Some of these technologies even exist as more than prototypes, although they’re sequestered away under military control.

The bad news is that our international space policy and governance lag behind our technologies. Orbital debris has reached its current disastrous status largely because during the last decade—and there’s no other way to put this—a giant pissing contest has played out in orbit between factions in the US and Chinese militaries.

“Almost every Air Force general I talk to says, ‘We’re going into space.’ For them, that really is the ultimate high ground, and they’re bedazzled by the technology—concepts like Rods from God and bombers that rise into orbit then drop directly down on a country with no overflight requirements—and their hopes that this will somehow validate strategic bombardment,” said John Arquilla, a Pentagon consultant and professor at the US Naval Postgraduate School. “Unfortunately, an arms race in space will only create a catastrophe for everybody, including themselves. The simple fact of the matter is that you can destroy or cripple things in orbit far more easily than put them up there.”

The Chinese proved this handily with their 2007 ASAT test. In one shot, they fragmented one of their own 750-kilogram satellites, creating a 20-percent increase in total debris. Not to be outdone, the US Air Force demonstrated its superior ASAT prowess a year later by knocking down a failing American satellite surgically, showing it might in theory destroy Chinese space assets without generating so much debris that its own hardware would be threatened.

In practice, this capability would be irrelevant if a conflict reached the point where both sides took potshots at each other’s satellites—the Chinese could simply try to destroy as many satellites and create as much debris as they chose. It’s hard to see the Air Force’s strategic thinking here as more than a sclerotic carryover from MAD-based nuclear deterrence doctrine. Both sides’ behavior, moreover, is especially regrettable because orbital debris growth was previously slowing. As McKnight laments: “We were doing a lot of good stuff and it was ruined in an instant.”

The “good stuff” came about in large part thanks to Donald Kessler’s landmark 1978 paper, “Collision Frequency of Artificial Satellites: The Creation of a Debris Belt.” That sufficiently impressed NASA that it had Kessler head an Orbital Debris Program. By the early 1980s, following that program’s recommendations, NASA had McDonnell-Douglas design its Delta boosters so that once their missions end, they vent any energy left (as residual fuel or in their batteries) to prevent debris-generating explosions, then drop into a decaying orbit and burn up in Earth’s atmosphere. Subsequently, this approach to passivation became standard operating procedure internationally.

As such, we wouldn’t be where we are with orbital debris in 2014—that is, facing Kessler-type growth—if international policy and governance had reigned in US and Chinese military knuckleheadedness. As we examine the challenge’s technical scope and potential solutions, we should remember that no technological fix, however brilliant, will matter much without international agreements that prevent the creation of debris.

Risk management

Even without such an agreement, the problem of orbital debris is a problem of risk management in a context and scale that’s unprecedented. Any solutions must factor in the following questions: What are the different categories of threat posed by orbital debris? How much time do we have and what should we prioritize? And what potential debris removal technologies might we have in our toolbox?

In terms of threats, the nearly instantaneous cataclysm Gravity depicts has almost zero chance of happening. The film’s scenario, an ASAT test at the same altitude as the International Space Station, would actually play out very differently in the real world. After the initial event, the likelihood of the ISS encountering any debris would be extremely low (at 10 seconds afterwards as low as 4×10-11) unless the ISS hit the debris cloud full on. Thereafter, the ISS’s chances of encountering the expanding cloud would grow but remain low (reaching 4×10-6 per orbit six months later) as debris increasingly dispersed and some of it burned up in Earth’s atmosphere.

A single impact on the ISS would also be far likelier than the multiple debris impacts that tear through it in Gravity. After all, though China’s 2007 ASAT test smashed a 750-kilogram satellite into a vast number of fragments, none of them have managed to collide with another tracked object since.

Any real-world Kessler-style cascade would be a slow-grinding, exponential process, probably requiring two to four decades to really kick in. If current debris growth is sustained, McKnight reckons, it’ll be 2035 before there’ll be, say, one collision involving a large object occurring annually in LEO. The bad news, McKnight adds, is that the current growth rate may not hold: the situation has become non-linear (he uses the term “mathematical singularity”).

“Before the Iridium 33 and Cosmos 2251 collision in 2009, those two objects’ potential conjunction wasn’t rated as even one of the 150 most likely that day,” he said. “It wasn’t even the likeliest collision for an operational Iridium satellite.” Nevertheless, when those two satellites smashed into each otherat a combined speed of 42,120 kilometers per hour (26,172mph), the result equaled over six years of typical debris growth. Hence, we entered potential “black swan” territory.

Thanks to this situation, any technical solutions to the problems of orbital debris have to begin with improved space situational awareness, or SSA.

At least, that’s the case according to Richard Crowther, the UK Space Agency’s Chief Engineer. He heads that country’s delegations to various UN and EU committees on orbital debris. Beyond preventing collisions, Crowther said better tracking of near-Earth space is vital for other reasons. “If treaties require removing spacecraft when their working lives end, we need to measure compliance. If an anomaly is encountered in orbit, we have to differentiate between natural phenomena and hostile actions.”

The US recognized the importance of SSA early, Crowther noted, yet even the American system has gaps over Earth’s Southern Hemisphere. Other nations have far more limited coverage, as good SSA requires a globally distributed, integrated network of radars and telescopes. Unfortunately, SSA remains primarily the province of national militaries, so there’s a reluctance to share data (the US being the exception) even when it’s in everybody’s interests. “The data largely is out there, but those who possess it tend to keep it to themselves,” Crowther said. He believes we won’t come to grips with orbital debris until an international data-sharing arrangement lets us understand the totality of what’s up there.

Three issues, one laser broom

Not only is there a lot of orbital debris to track, but there’s no single answer about what to do with it. The briefest consideration of the highly varied nature and distribution of debris means that a one-size-fits-all technological solution is probably impossible. From a risk management viewpoint, there are three categorically different challenges that removal technologies will need to address.

The highest priority is de-orbiting sizable items from orbits where the greatest collision risks exist. Here the possible solutions include electromagnetic tethers, grapples, tugs, and inflatables and solar sails (the latter delivered by nanosatellites). On reaching their targets, most of these technologies would require months or years to complete their task. But that task is preventative—to de-orbit large debris before it collides and fragments—and the real risks of those collisions lie two to four decades ahead.

The second challenge is that we think those risks lie two to four decades ahead. However, debris density has advanced far enough toward a Kessler-type situation that the chances of black swan events (like the Iridium-Cosmos collision) are significant. Worse, tracking may reveal two orbiting objects at imminent risk of collision when we have no way to respond—unless some kind of unmanned space tug can be rapidly deployed. Such a rapid-response spacecraft would require a high degree of thrust and maneuverability, and it must be a high-mass object itself. That might seem an unrealistically tall order, except that such a spacecraft—or something very much like it—is already being operated by the US Air Force.

Third, there will be some need to develop collection media that can deal with clouds of small debris fragments. Nobody wants the enormous expense and growing pains of developing and deploying such technologies, but the situation will resemble the clean-up after a massive oil spill. That is, everybody would prefer that matters never reach that point, but if enough orbital collisions start occurring, the technologies need to be available.

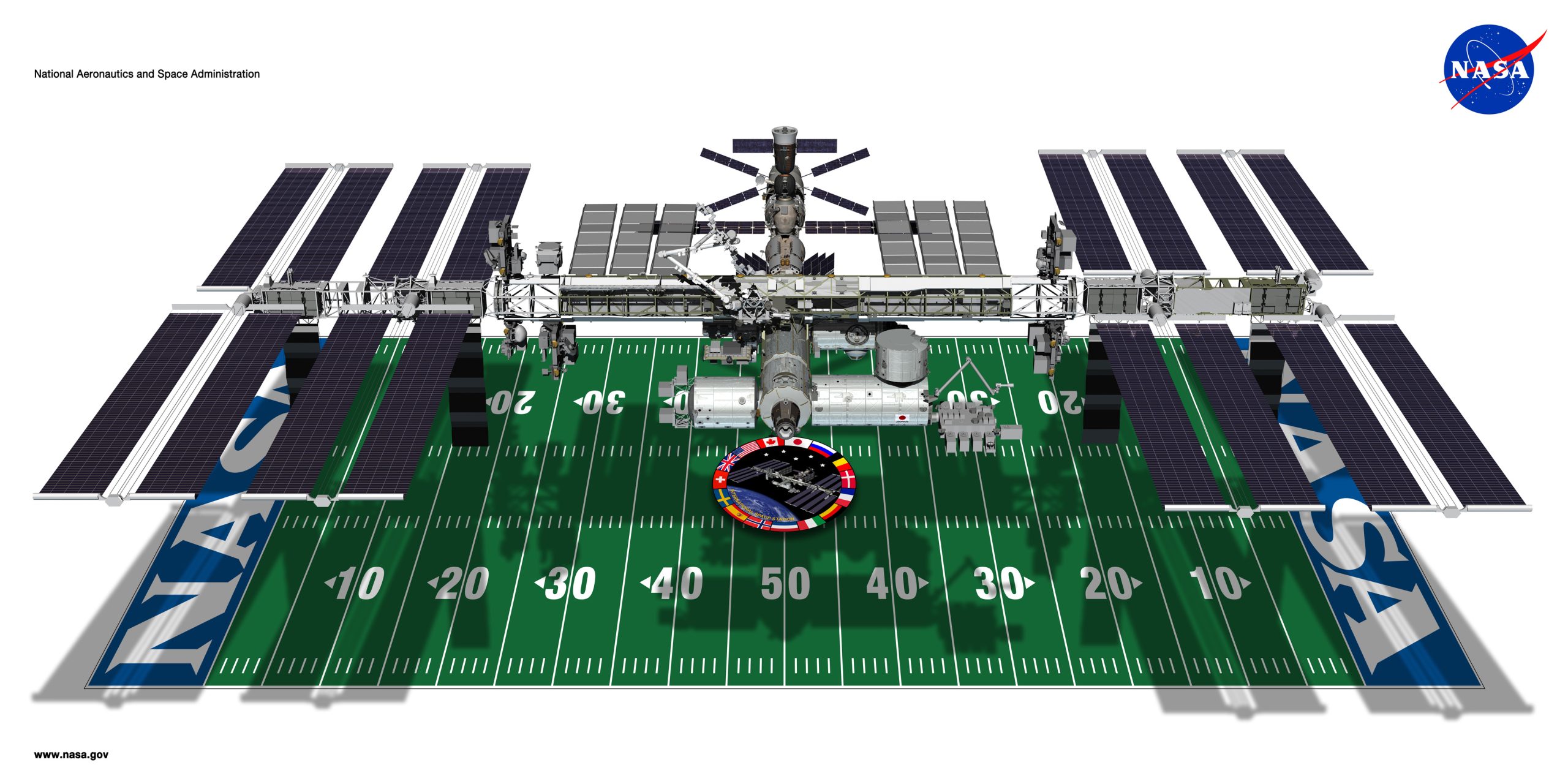

For scale purposes, look how big some of the stuff we put into space is. Credit: NASA

Weighing priorities

Why are high-mass objects the top priority? Simply put, so much of what we put in orbit is still in this form. For instance, there’s the football-field-sized ISS with its acre-wide solar panels—a habitat so big that, according to Colonel Chris Hadfield, one could spend a whole day aboard without encountering another crew member. But there are also some 1,800 derelict rocket bodies and 3,200-odd satellites (about 1,000 operational), which comprise most of the mass hefted into orbit throughout the decades. In this class of larger-scaled objects, two-dozen Russian SL-16 Zenit boosters, each massing 7,529 kilograms (equivalent to 8.3 tons), are clustered in a particularly crowded segment of LEO.

Applying a metric of collision probability multiplied by mass, those Zenit boosters are high-priority candidates for removal whenever we get serious about orbital debris remediation. As McKnight points out, “Removing mass from orbit as one large object of several thousand kilograms rather than as tens of thousands of fragments after a catastrophic collision will be at least an order of magnitude less expensive and quicker to execute.”

One proposed solution is the so-called laser broom: a powerful ground-based laser pulsing at an orbital target. The idea is to ablate the object’s front surface so the resulting plasma produces a retro-rocket-like thrust that slows it down. The drag of Earth’s upper atmosphere does the rest, and it reenters and burns up.

On its face, this concept has much in its favor. To start, it’s well researched. The Orion Project, a 1995-96 study by NASA and the US Air Force, concluded that a ground-based laser system was both feasible and far more economically efficient than launching mechanical systems to grapple individually orbiting objects. Furthermore, if someone wanted to do a near-zero-cost demo, the necessary technology exists right now in the form of the Starfire Optical Range. That belongs to the Directed Energy Directorate at Kirtland US Air Force base, and it’s currently used for tracking and imaging satellites. But if it were a perfect solution, it’d be in progress already.

“There are reasons that Orion final report has been on the shelf for more than a decade,” said Nicholas Johnson, Chief Scientist for NASA’s Orbital Debris Program. Physics-wise, the concept’s main downside is that pushing around objects with serious mass would only work incrementally.

A 2011 study by experts at Sandia, Lawrence Livermore, and various private firms evangelized for an improved laser design as the only technology capable of taking down debris of all sizes and at all altitudes, including geosynchronous orbit (GEO), 35,786 kilometers above Earth. Yet even this improved laser, according to the study, would require a minimum of 3.7 years to de-orbit one large object with a mass of 1,000 kg. It would therefore need 27 years and eight months to de-orbit one of those Zenit boosters.

There are other problems. If a ground-based laser’s pulses don’t hit an orbiting object with total precision, the result might be a diffused ablation jet that isn’t effective, or worse, triggers its break up. This risk is enhanced if the object happens to be tumbling or spinning.

Ultimately, it’s the technology’s dual-use potential that currently blocks its deployment. NASA’s official position is that any laser broom proposal is dead on arrival since any laser able to blast a satellite sufficiently to de-orbit is a potential ASAT weapon—as well as a technology that might help create an effective ballistic missile defense.

“The technology is there,” said Michael Krepon, director of the Space Security program at a global security think tank called the Stimson Center. “The US isn’t the only one who has it.” It’s naïve to assume, Krepon suggests, that if the US started firing high-powered lasers at orbiting objects, the Russians or the Chinese couldn’t do the same. Since that would be far more destabilizing for the international status quo than the US-China faceoff we’ve already had, nobody wants to go there.

Not yet, anyway. It would be nice to think that, alongside the international SSA data-sharing arrangement that the UK’s Crowther advocates, countries could reach an agreement to establish an internationally operated laser installation. One study prices such an installation at $300 million; if it eliminated 300,000 pieces of orbital debris, that’s $1,000 per object. This would make the laser broom concept easily the most cost-effective means of dealing with debris, and that’s on of top it being able to deal with both large and small debris items.

That size-agnosticism needs to be stressed, since high-mass objects like those Zenit boosters are just the biggest of 22,000-plus items larger than 10 cm that the Pentagon currently tracks. Below that 10cm scale, a half-a-million-plus debris pieces, sized anywhere from 1 to 9cm, are circling in LEO at up to 18,000mph. A collision with a 5mm–10cm-size object will still terminate a satellite or manned mission. Even with sub-millimeter-sized debris, satellites have failed after being hit. Dozens of Space Shuttle windows had to be replaced because of small-scaled debris impacts.

Other solutions

Does another technology besides the laser broom look versatile enough to handle both the small-scaled debris and the big-mass items? At present, not really. For now, the likeliest options for small debris removal are some form of “collection media,” such as aerogel, which NASA already uses to catch comet dust. Aerogels—derived from gels where the liquid component has been replaced with a gas—might be shaped into huge spheres by inflating balloons in orbit, thus presenting large cross-sections for debris to collide with. How effective such measures will be at sweeping volumes of space is uncertain, though. Estimates for the implementation costs come as high as one trillion dollars.

A small glimpse at aerogel capabilities—that’s a trio of crayons on aerogel over a flame. Credit: NASA

Costs of that scale reinforce the message that it will be much less painful to remove several tons of orbital debris as a single body rather than as millions of fragments. But with directed-energy systems like the laser broom politically unacceptable, any technology that does get deployed will entail direct physical capture of debris—with large- and medium-sized debris items, that means individually rendezvousing and grappling with orbiting objects. This has been done before for select missions like the Hubble Space Telescope’s repair, but developing the capability to grapple with objects that often are tumbling or spinning dangerously in orbit will be far more difficult.

Perhaps the most promising of these grappling technologies is the electrodynamic tether, sometimes called an EDDE (or ElectroDynamic Debris Eliminator). The basic concept is simple: a wire in a magnetic field—Earth’s magnetosphere, in this case—through which a current is run to produce (as per Faraday’s Law) a force at right angles both to the wire and the magnetic field. Here, the wires would be between 2 to 30 km (1.2 to 18.6 miles) long to generate significant force. The possible applications go beyond orbital debris removal. An electrodynamic tether also could further the passivation policies most spacefaring nations now follow. When a satellite’s or rocket’s mission ends, an onboard tether would be rolled out to slow that spacecraft so it de-orbits, then burns in the Earth’s atmosphere.

The potential for reusable autonomous tethers also exists. This would be a hypothetical system with, say, a mass of 100 kg (220.5 lbs)—easily launchable as another spacecraft’s secondary payload. Once unwound, it might extend 10 km with two kilowatts of current running through it. That would generate sufficient force to alter its orbit by a couple of hundred kilometers daily. According to Joe Carroll of Tether Applications Inc., a reusable tether system could push a large debris item down into a controlled re-entry trajectory, raise itself, and move on to another object at a rate of about one object per week. “Twelve of these things could basically deal with the orbital debris problem in five years,” Carroll maintains.

Today, that assertion remains substantially untested, so financial estimates are sketchy. Still, an autonomous electrodynamic tether performing multiple debris-removal missions without needing other propulsive capabilities might cost as low as $100,000-500,000 per object removed, according to a feasibility study done by contractor Star Inc. for the US Navy.

The technology’s downsides, physics-wise, are being addressed by a test tether, JAXA’s STARS-2 . The Japanese have woven three wires into a net-style electrodynamic tether to beat the initial structural stresses, like friction, that are inherent in uncoiling a very long wire. The net design also limits the likelihood of a single-stranded tether becoming severed by a debris particle—a probability that’ll grow as orbital debris increases.

Nanosatellites are another approach to debris removal. Defined as microsatellites sized 1 to 5kg (2 to 11 lbs), these are a rapidly expanding market. Moore’s Law and modern electronics’ general advance have crammed ever-greater capability into ever-smaller satellites. Orbital debris removal is now one task for which such satellites are being designed. Representative projects here include the CleanSpace initiative at the Swiss Space Center at Ecole Polytechnique Federale de Lausanne, which is developing nanosatellites that will extend gripping devices to fasten to their targets; and the CubeSail nanosatellites produced by Vaios Lappas’ lab at the University of Surrey, which will release 5m x 5m solar sails made of mirrored membranes in LEO so they can then de-orbit objects of up to 500kg (~1100 lbs) mass.

From a risk-management viewpoint, both electrodynamic tethers and nanosatellites belong in our primary category of debris removal technologies, able to shunt rocket-bodies and satellites around in LEO. Of course, the US military has been in that game for a while. Almost a decade ago, a US Department of Defense employee told this writer, “We’re developing something called ANGELS. They’re autonomous nanosatellites that help us to move our satellites to safer locations and to rapidly reconstitute space assets.”

If you suspected that, in 2014, US military might be where you’d find emerging technology that could do rapid-response orbital debris removal—in our risk-management analysis, the second category of necessary technology—you’d probably be right. And if you also suspected such technology might resemble the Air Force’s X-37B Orbital Test Vehicle, you could be correct about that too.

Since the X-37B is heavily classified, there’s no way anyone without the necessary clearance can know what it’s doing with certainty. Still, the X-37B is descended from the X-37, a NASA-Air Force project aimed at an unmanned reusable space-plane. Essentially a robotic mini-version of the Space Shuttle, this was meant to rendezvous with satellites to refuel them and replace failed parts. In 2004, the project was transferred from NASA to the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), which classified it and made it the Air Force’s exclusive domain, where it remains.

The feasible future

It’s clear that we’ve got plenty of unclassified technologies ready to test alongside classified hardware that may be even more sophisticated. So let’s return to the question we started with: how far do current international policies and governance lag behind the LEO debris situation and our potential technological solutions?

Far behind. Today, under the 1967 Outer Space Treaty that dictates existing space law, if one of those dead Zenit boosters were in imminent danger of colliding with another nation’s functioning spacecraft, it’d be illegal for anybody but the Russians to touch the thing. Currently, space law says that nations retain jurisdiction over their non-operational spacecraft in perpetuity (unlike maritime law Earth-side, where salvage law applies).

There are signs of change. The third draft of an International Code of Conduct, or ICoC, for responsible spacefaring nations was released last year by the European Union. It moves usefully toward managing space traffic and debris. Moreover, as the Stimson Center’s Krepon noted, “For the first time, Beijing and Moscow have endorsed an official code of conduct in principle, so that’s new ground.”

Unfortunately, Chinese and Russian agreement in principle doesn’t extend to the actual EU draft. “Privately, the Chinese give two objections in private,” Krepon explained. “Firstly, they object to language in the ICoC draft referencing the fundamental right nations have in the UN charter to self-defense.” According to Krepon, since the Bush II administration, the US has claimed an anticipatory right of self-defense. So the Chinese might understandably resist seeing that applied in space. “Secondly, though, they also object that the ICoC covers military uses of space, while they prefer it cover only civil and commercial ones. Given their first concern, that’s fairly self-contradictory.”

Both Beijing and Moscow have been pushing since 2008 for a treaty banning systems “specially produced or converted” to be weapons in space. However, Krepon said this treaty exempts ground-based systems. This exemption covers, effectively, most systems that’d actually be deployed in any conflict in space today, including ASAT kinetic missiles—probably the first items a space weapons treaty should ban, since they create the most debris.

But figuring out what not to exempt is challenging. “The notion of banning weapons in space rests on being able to define them,” Krepon also noted. “I haven’t yet heard a definition that’s verifiable and meaningful when dealing with these multiple-purpose technologies.” If kinetic ASATs actually were banned, would it cover any medium-range missile, ICBM, SLBM, or missile defense interceptor that might also be used for that purpose? Unless weapons inspectors could examine such a missile’s programming, its purpose wouldn’t necessarily be evident. “I seriously doubt that this problem can be surmounted,” Krepon says. “The Russian and Chinese draft treaty is not a serious document.”

So what are the prospects going forward?

Krepon, for one, isn’t hopeful about the Chinese signing on to any grand international space agreements soon. “In the near term, it’s possible that this ICoC, sensible though it might be, will remain a hostage to poor relations between the US and China, and the US and Russia,” he said. And pessimistic as that may seem, Krepon is in the arms control business, so he may be a little too optimistic. Official doctrine for both the Chinese and US militaries is that the two nations are each other’s greatest future military threat. Each has developed strategies targeting the other’s key space assets. Military brinksmanship in LEO will likely recur.

Sadly, this isn’t an area where we can expect to see the private sector leapfrog governments. Commercial space operators will resist spending any money on top of expenses that presently begin with launch costs of approximately $5,000 for each kilogram placed in LEO. As Nassim Taleb stressed in his book, The Black Swan, a black swan event only has to be so rare or unpredictable that most people ignore its possibility—and the precise timing of the next serious debris-creating collision is inherently unpredictable. Here in 2014, the most likely prognosis is that research into orbital debris removal technologies will get funded, but no serious deployment of those technologies will take place before the next catastrophic event occurs. That, most likely, is in the 2015-2018 time frame.

At that point, people will sufficiently sober up and start realistically weighing the high costs of deploying these technologies against the ever-greater costs of waiting. In the meantime, the clock is ticking.

Mark Pontin is a science and technology writer who lives in Berkeley, California.

Listing image: NASA