“Our meter is perfect,” Comcast rep claims. It isn’t—and mistakes could cost you.

On March 18, Ars received an exasperated e-mail from the father of one very frustrated Comcast customer.

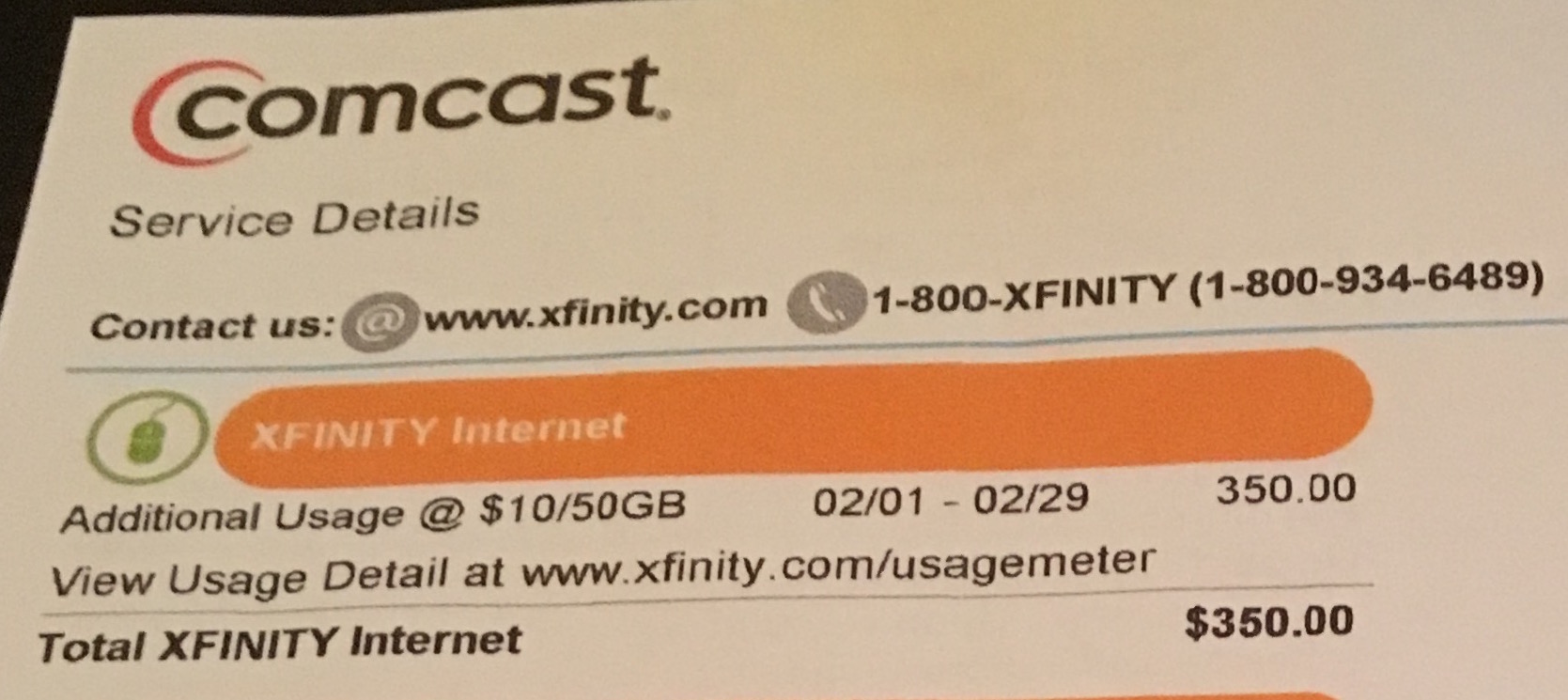

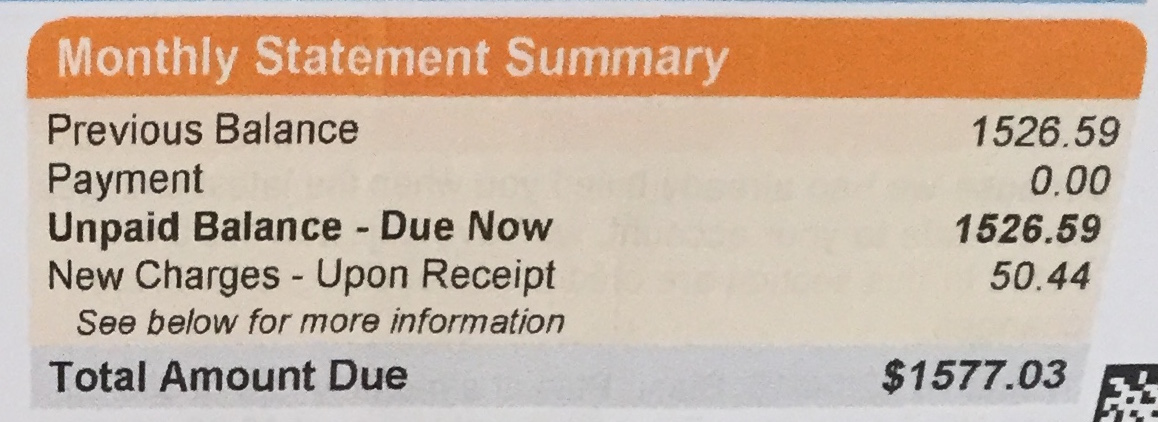

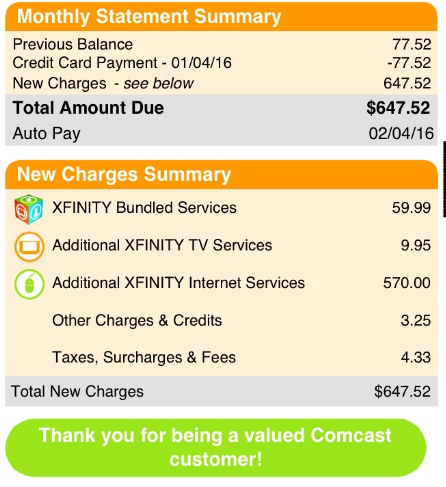

Elliot told us that his son, Brad, had received bills totaling more than $1,500, and Comcast alleged that Brad had been consistently using far more than his 300GB monthly limit. Overage charges of $10 for each additional 50GB were piling up as Comcast’s meter claimed usage totaling multiple terabytes a month. In February, there were $350 worth of charges for 1,750GB of usage above the 300GB limit (about 2TB total). In January, there had been $570 in extra charges for 2,850GB above the 300GB limit (about 3TB total).

No one had any idea why Comcast’s data meter was producing such high readings, but the cable company wasn’t budging on the amount owed. Brad and his girlfriend, Alison, each 23 and living in Nashville, were working long hours and not using the Internet enough to consume terabytes per month, they say. Making just enough money to cover rent and college loans, they canceled their Comcast Internet to prevent more overage charges, and disputed the amount owed.

In his initial contact, Elliot told us:

So far, despite all the calls we have made, no one is willing to even provide us with one shred of proof this data was consumed, by what method or website(s) it was used on. They just keep telling us to trust them, the data was used. We have asked for investigations of the Internet history to prove this usage, and they say they will do so, but they never do.

We have had many conversations about this case with Brad, his father, and a Comcast spokesperson over the past few months. Though Elliot lives elsewhere, his name was added to the account to help sort out the billing problem. (Brad asked us not to publish his last name.)

Shortly after Elliot e-mailed us, Comcast had bill collection agents contact Brad. They were only called off after Ars relayed a message from Brad’s father to the Comcast media relations department, which in turn told the company’s employees to halt the collections process. Comcast also waived all of Brad’s charges, but hasn’t admitted any fault in its data usage measuring system.

Many other customers of Comcast and other ISPs also haven’t been able to get problems addressed properly without alerting the media. Brad is merely one of several Comcast customers who has contacted us after facing similar data cap problems. In all cases, Comcast’s first response is to tell customers that its meter is accurate and should not be questioned.

“We know that our meter is right… with our meter, we give you a guarantee that it is perfect,” one Comcast customer service representative insisted to another subscriber who disputed data charges a few months ago. That subscriber, Chris from Georgia, had been measuring Internet usage on his own router and found big discrepancies between his own measurements and Comcast’s. We’ll have more on Chris and other customers later in this article. First, let’s tell Brad’s story.

A shocking bill

Brad and Alison signed up for Comcast in August 2015. The high data readings began shortly thereafter, exhausting the three “courtesy” months Comcast provides before charging overage fees. (Comcast recently lowered the number of courtesy months to two.) In June of this year, Comcast began offering Nashville consumers the option to buy unlimited data for an extra $50 a month, but that choice wasn’t available when the company accused Brad and Alison of going over their data cap.

Brad couldn’t figure out why Comcast’s meter said they were using so much data, and a few more months of high readings and overage fees followed. Brad is a full-time computer technician who is also going to school, and Alison is a nurse. It’s not uncommon for them to watch a few hours of Netflix after work. But they don’t work at home, don’t run any servers, and don’t do much gaming, he said.

“I mean, realistically, I’m sure it is in the couple hundreds of gigabytes,” Brad said, “but it’s not near a terabyte.”

Netflix high-definition video can consume up to 3GB per hour. At that rate, you’d have to watch for more than 33 hours every day to hit the 3TB Brad and Alison supposedly used in a single month. (Note: there are 24 hours in a standard Earth day.)

Wait, the bill is how much?

Getting answers from Comcast was anything but easy, as Elliot told us:

We have tried to reason with everyone we have been able to speak with that it is just not possible for these two kids to be using this much data. They would have to be downloading some massive files 24/7 for this to be possible. No one will listen to reason or offer to help in any way.

Brad estimated that he, Alison, and his father had talked to Comcast about 20 times combined, all without success. One time, Brad was on the phone with Comcast about a notification that he’d reached 90 percent of the data allotment only five days into the month. Minutes later, while talking to a Comcast employee, “I got a message saying I reached 115 percent of my usage,” he said.

Comcast did some basic troubleshooting to make sure no one was stealing Brad’s Wi-Fi access and that there was no malware causing the problem. Nothing nefarious was found in these quick investigations, and the MAC address on Brad’s modem matched the one in Comcast’s system.

Shortly after Ars first spoke to Brad, we sent some questions to our contacts at Comcast. We were still waiting for answers when, at 5pm on Friday, April 1, Elliot told us that the account had been sent to collections. “The bill collectors have been in touch already” by phone and mail, he said. We then e-mailed the Comcast spokesperson who was handling the case, and the rep had a quick reply: “That should not have happened.”

Within an hour, Comcast called Brad and waived all the charges.

At this point, the case seemed to have been resolved in much the same way as an earlier case Ars had written about in December 2015. In that instance, a customer discovered a flaw in Comcast’s data cap meter, and the company eventually admitted that it had recorded his MAC address incorrectly, causing the high readings.

But in some ways, this is where our latest story really begins. With all charges against Brad waived, we were getting ready to write an article about this situation in April—but then, a Comcast spokesperson told Ars the company wasn’t admitting any fault in its data meter. Comcast had checked the data and found that it was all accurate.

We challenged Comcast to prove its meter accurately measured Brad’s usage. This set off a months-long process that began with Comcast asking Brad to test all of the Internet-connected devices in his home. Ultimately, Comcast decided that Brad’s Apple TV was at fault, but the company provided no data to back up its assertion. Brad even sent his Apple TV to Apple for further testing, and Apple confirmed to Ars that the device was working properly.

The tests

Comcast was able to test Brad and Alison’s data usage because they re-subscribed to Comcast Internet service. Though neither of them work from home, Brad’s employer was able to help him get a discount on Comcast Business Internet, which has no data caps.

Comcast said that Brad’s data readings were still high on the new business class service, even with a new modem. We asked Comcast to provide data usage readings, but Comcast refused to provide that information. The company doesn’t provide usage readings to business class customers because they don’t face caps, and a Comcast spokesperson told Ars that Brad should have been on a business account all along. The spokesperson also claimed that Brad’s data was “legitimate business use,” but provided no evidence to back up this assertion.

Comcast decided to conduct extensive troubleshooting with Brad to determine what (if any) device was using abnormally large amounts of data. Troubleshooting involved inventorying and temporarily unplugging every Wi-Fi-connected device in Brad’s home, one by one, to determine whether data usage was affected. This took weeks. Comcast said it also tested the node outside Brad’s house and replaced equipment serving the house to make sure there wasn’t a network infrastructure problem.

Keep in mind that Comcast only did this extensive troubleshooting after Brad started talking to the media. The Comcast technician was “really nice and he helped out, but I just wish they would have done all this work before we got [the billing problem] fixed,” Brad told Ars.

The troubleshooting revealed more oddities about Comcast’s measurements, according to Brad.

In one case, a Comcast tech told Brad that he used a lot of data over a couple of hours, “and I was like, ‘well that’s interesting because I wasn’t even home at that time.’” Brad next asked what Comcast’s data meter showed for the previous day during a four-hour stretch when he was watching online video. The Comcast tech answered that data usage was low during those hours.

Unplugging various devices one at a time didn’t initially cause any major drops in usage. Finally, Comcast said that Brad’s new Apple TV must be to blame, since the data readings allegedly took a big dive when he turned it off for a day.

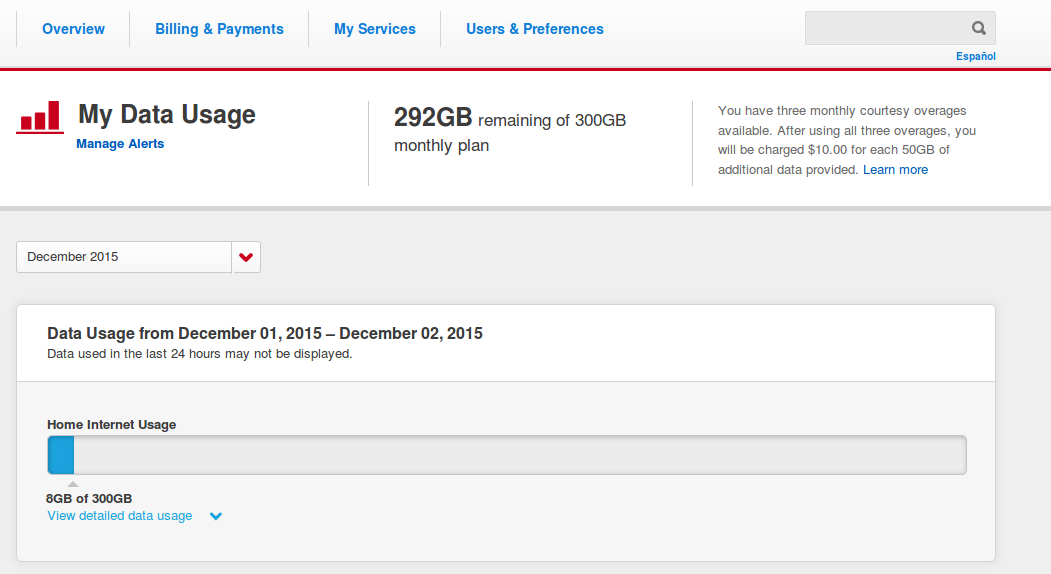

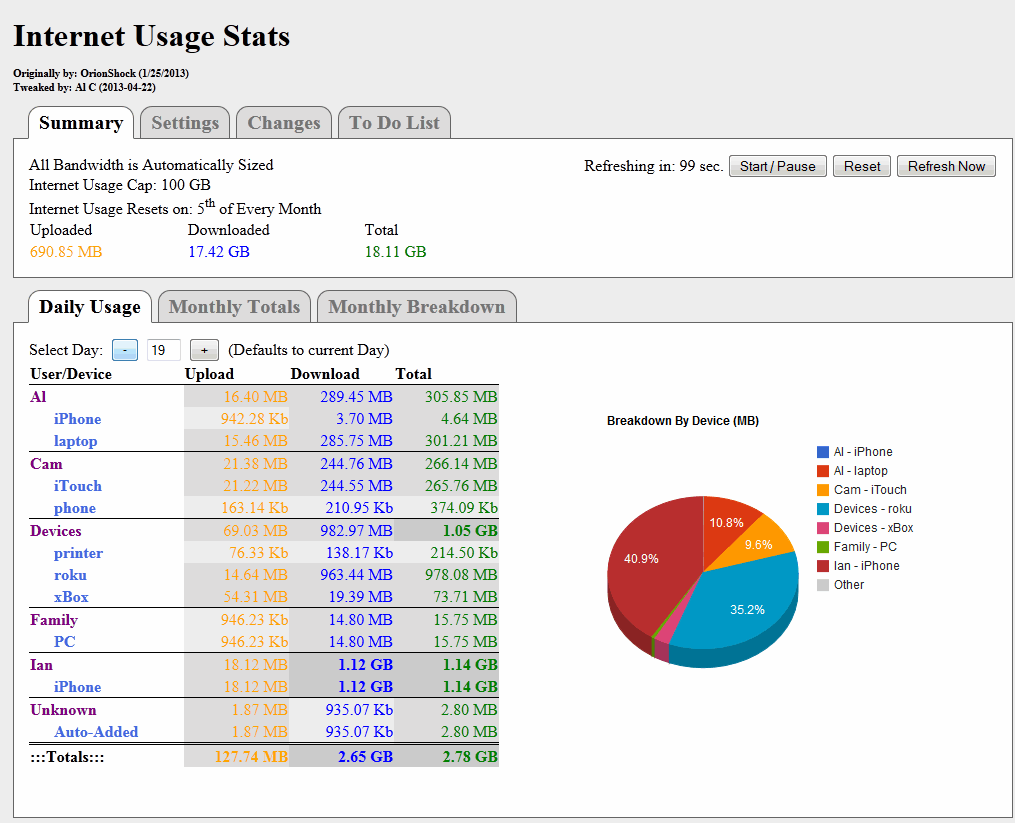

This isn’t Brad’s data readout, but it shows what Comcast customers see when they check their usage on Comcast’s website.

This isn’t Brad’s data readout, but it shows what Comcast customers see when they check their usage on Comcast’s website. Credit: Comcast support forum.

But Comcast refused to provide us with specific data, and there’s reason to doubt that Brad’s Apple TV was the culprit. Comcast suggested that Brad disable a setting that caused the Apple TV to download new video screensavers each week, and the company says his data usage has been reduced to normal levels since he did so.

There are a couple of problems with this theory. Brad told us that he turned the screensaver download feature back on, yet Comcast’s spokesperson says that the data usage measurements continued to show a big reduction. Additionally, even if the video screensavers were set to download daily, they would only account for about 18GB of usage a month. Each download is about 600MB, and the default download frequency is monthly.

Comcast continued to insist that the Apple TV was to blame and even contacted Apple to relay its suspicions. As a result, Brad sent the device to Apple so the company could perform diagnostics. (Apple provided Brad a replacement device during the testing.) Apple tested the Apple TV and found that it was working properly; they found no problems that would cause unintentional data usage in the multi-terabyte range.

“Apple tested and viewed the device and did not find anything wrong with the device,” an Apple spokesperson told Ars on July 25.

The months of testing, without any firm conclusions, raise one question with no straightforward answer. If Comcast, the nation’s largest Internet provider, can’t determine what’s pushing its subscribers over their data caps, why should customers be expected to figure it out on their own?

On top of that, few customers other than Brad receive such extensive testing. And even that testing would never have happened if his father hadn’t contacted a journalist.

Complaints flood in, but data caps are here to stay

Comcast has been steadily implementing caps in new markets to gauge customer reaction before a possible nationwide rollout. The ISP now enforces them in 14 percent of its territory.

Customers have flooded the Federal Communications Commission with complaints about the caps, but no amount of protest seems likely to kill the limits and overage fees altogether. Overage fees provide a new revenue stream and simultaneously make it harder for customers to dump their Comcast TV subscriptions to watch only Netflix and other streaming video.

Comcast has made changes to its data caps in response to customer outrage. In addition to offering unlimited data for an extra $50 a month, Comcast has boosted the cap to 1TB a month and limited overage fees to $200 a month. (Comcast’s meter reports binary numbers rather than decimal numbers, meaning that 1GB is 1.073 billion bytes instead of an even billion. In keeping with the binary counts, the new 1TB data cap is 1,024GB rather than 1,000.)

Checking Comcast’s math

Some Comcast customers accused of using too much data have attempted to prove the cable company’s meter is faulty by running tests with open source router firmware such as DD-WRT. The customers’ own measurements sometimes indicate that they’re really using less data than Comcast claims, but home measurements aren’t perfect, and Comcast employees are loath to admit any potential problems in the cable company’s meter.

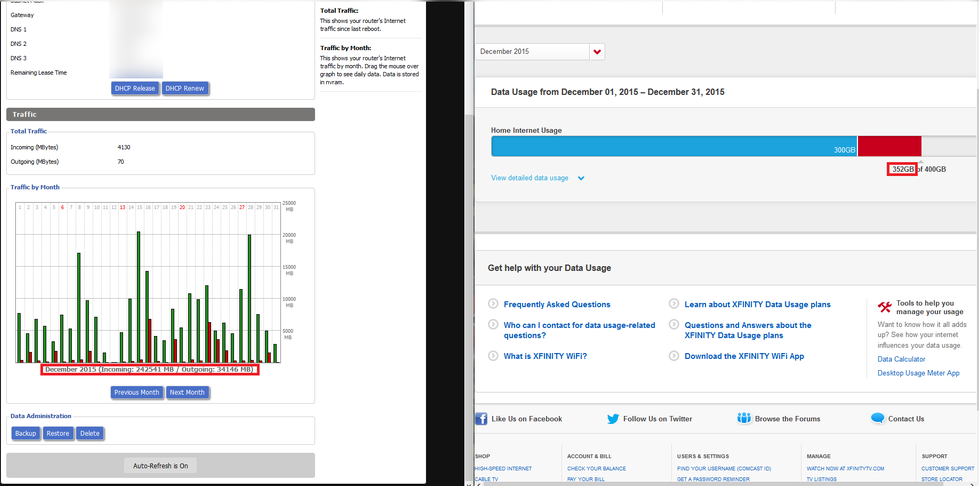

Chris from Georgia, mentioned above, found discrepancies of up to 75GB per month between Comcast’s meter and DD-WRT. The higher Comcast readings put him over the 300GB cap and triggered a $10 overage charge after the courtesy months were exhausted.

Chris’s data usage in December 2015, as measured by his router and Comcast.

A Comcast customer service representative was not impressed by Chris’s measurements. Chris sent us a recording he made of his conversation with the rep, who said, “We have the meter, and we cannot kind of get into the speculation that your meter is right or wrong, but we know that our meter is right.”

Chris explained that DD-WRT is well-known, reputable software, and it was measuring all Internet activity in his house. “I’m measuring the activity that’s going over the WAN port on the router that’s directly plugged in to your [company’s] modem,” he said in the call with Comcast.

The Comcast rep told Chris that any home monitoring software is “just maybe roughly giving you an idea. But with our meter, we give you a guarantee that it is perfect.”

Comcast: Data caps are “pro-consumer”

Chris filed a complaint with the Federal Communications Commission, and he provided us with Comcast’s written response to the FCC and himself. Since the vast majority of Comcast customers use less than 300GB a month, Comcast said its data cap is a “pro-consumer policy [that] helps to ensure that Comcast’s customers are treated fairly, such that those customers who choose to use more, can pay more to do so, and that customers who choose to use less, pay less.”

Comcast customers with the standard data cap don’t actually pay any less money when they use less, though. The only option for Comcast customers to pay less is to sign up for a 5GB-per-month plan that’s $5 cheaper than a standard plan. Two hours of HD Netflix video is enough to exceed 5GB. Customers on this “cheaper” plan lose the $5 discount and start racking up overage charges as soon as they hit 6GB in a month. It’s easy for customers who signed up for the discount to get charged more than if they hadn’t signed up for the discount.

Comcast’s letter to Chris pointed to research by NetForecast, “an independent auditor of ISP data usage meters” that found Comcast’s meter to be 99-percent accurate.

Despite the discrepancies and lack of information, Chris ultimately paid the overage fee. “I’m not going to contest it and get my Internet shut off,” he told Ars.

Comcast offices in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Credit: Cindy Ord/Getty Images for Comcast

How Comcast measures

Why is Comcast so confident in the accuracy of its meter and so dismissive of customers’ own measurements?

To find out, we spoke with Peter Sevcik, founder and president of NetForecast, the technology consulting firm that Comcast pays to conduct periodic assessments of its data usage meter. NetForecast’s measurements in 55 homes last year found that Comcast met its goal of 99 percent accuracy. Errors more often undercounted data usage than overcounted, favoring the subscriber.

Those 55 homes represent just a tiny fraction of Comcast’s 23.8 million broadband customers.

NetForecast places its own specialized wireless routers in customers’ homes to determine whether Comcast’s meter is accurate. Comcast itself doesn’t actually measure in customers’ homes; instead, Cable Modem Termination Systems (CMTS) in Comcast facilities count the downstream and upstream traffic to and from each subscriber’s cable modem. Modems are identified by their MAC addresses.

Although Comcast lets customers check the CMTS measurements of their data usage in an online tool, the company doesn’t provide any way for customers to verify the CMTS count by taking measurements directly from the modem. This is important not only because the remote measurements might be inaccurate, but also because Comcast might not accurately record a customer’s MAC address.

There is also occasional fraud, with one user’s MAC address being cloned and used by someone else to access the Internet from a different modem. Sandvine co-founder and CTO Don Bowman told Ars that a cable company could count data from these two users as one and bill the legitimate user.

This fraud is harder to pull off in the newer versions (3 and 3.1) of DOCSIS, the Data Over Cable Service Interface Specification used by cable companies. But it still occurs sometimes and is “very difficult to detect” without a cable company employee “manually investigating,” Bowman said. In another extreme scenario, a customer could be victimized by a denial-of-service attack, inflating their data “usage” through no fault of their own, he said.

What about Comcast getting MAC addresses wrong? In December 2015, Ars wrote about Oleg, a programmer from Tennessee who was accused of using 120GB of data while he was overseas on vacation. Comcast insisted that someone must have hacked into his Wi-Fi network and used the data. But when Oleg subsequently disconnected his cable modem for a week, Comcast’s meter kept counting data that wasn’t being used. Comcast finally admitted the mistake and said the company had entered his MAC address incorrectly.

Data used by visitors connecting to the public Wi-Fi hotspots broadcast by Comcast routers does not count against the home subscriber’s cap. Connecting to a hotspot requires a Comcast account, and the data usage “is tied back to the visitors’ accounts, not the homeowner’s,” Comcast says.

Cable companies offer no way to verify their data

While NetForecast equipment provides a complete “second, shadow meter system” in 55 customer homes, it would be “pretty expensive” for Comcast to put measuring equipment in every customer’s home, Sevcik told Ars. However, it would theoretically be possible for cable company modems to report how much data they are sending and receiving themselves, giving customers a way to verify CMTS measurements.

“Technically it could, but it’s never been implemented,” Sevcik said. “It’s just not in any spec. It’s not in the cards to go get this [data] out of the cable modem.”

A Comcast spokesperson told Ars that when there are disputes, “we always err on the side of the customer on data usage, and if there are questions we take them on a case-by-case basis and try to resolve [them].” While Comcast offers no way for customers to verify their data usage on the modem itself, the company says it has worked with NetForecast “to design something that’s incredibly thorough.”

The problems of home measurement

Sevcik cautioned that customers who measure their own usage with open source firmware should know the limitations of the method. Open source firmware like DD-WRT and OpenWrt generally counts traffic from Layer 3 and above in the classic seven-layer networking model, he said. According to Sevcik, the Layer 2 Ethernet frames that carry each packet thus aren’t being counted by home routers. Cable company measurement systems at the CMTS count those Ethernet frames, boosting the total data, he said.

On a very short packet, the Ethernet frame could boost the size by 60 percent, while on big packets the overhead could be as little as 4 percent, according to Sevcik. If you’re watching a Netflix movie, he said, about 10 percent of the data generally isn’t being counted by typical open source software.

In its report, NetForecast says that its system tests whether Comcast is meeting its goal to count “all subscriber-generated IP traffic across the subscriber’s Internet access line, including IP protocol management traffic and Ethernet framing.”

The report continues:

If you measure traffic in the network, you will see the payload traffic plus overhead from protocols like TCP/IP and Ethernet, which generally add up to about six percent to nine percent overhead to the payload traffic for large packets and a larger percentage for small packet traffic like VoIP. [NetForecast’s] meter system counts the traffic as seen on the wire, which includes the payload plus protocol overhead, so it should closely match the network view.

There’s no technical reason that open source software couldn’t count the Ethernet frame bytes. But the software mostly runs on consumer routers that are inexpensive in part because “they let chips handle many low-level functions,” such as the WAN Ethernet interface, Sevcik said.

“This simple Layer 2 function is handled in a chip and then passed on to the router’s CPU where the OS (typically Linux) is running and then finally to the DD-WRT software,” Sevcik said. If the router keeps track of this overhead in addition to the packets, “then it only requires simple math to reconstruct the Ethernet header/trailer usage and add it to the IP bytes. But that is an extra step someone needs to take if they want to correctly track cable industry usage meters.”

Perils of packet loss

Packet loss can add to Comcast’s data count, since dropped packets are automatically re-transmitted. If the loss occurs between Comcast’s CMTS and the customer’s modem, the packet will be sent again and counted a second time by Comcast, despite being seen only once by the customer’s equipment at home. This can also affect upstream traffic. Packets sent from a Comcast customer to a server on the Internet could be counted twice if they are lost on their way from the CMTS to their final destination.

Packet loss can also reduce Comcast’s count. If a subscriber has to send a packet twice because the first one is dropped before arriving at the CMTS, only the second is counted by Comcast. Overall, the impact of packet loss on the meter is small, Sevcik said.

Other simple problems could arise in home testing. Network gateways provided by ISPs to consumers often include both a modem and wireless routing capability in a single box. Customers who install DD-WRT or other open source software generally do so on a separate wireless router that they own themselves. But if the customer doesn’t disable the wireless functionality on the cable gateway, it’s possible that some devices in the home are still connecting directly to the gateway, bypassing the router’s measurements, Sevcik said.

NetForecast says it recently discovered a home router that appeared to count properly but was really just counting usage for devices added to the network after the most recent router reboot. Newly connected devices were only added to the router’s DHCP table after each reboot, and routers often go weeks or months without being rebooted.

Home counting problems don’t let ISPs off the hook

While taking a customer’s router measurement as 100 percent reliable might not be possible, that doesn’t mean Comcast and other ISPs are infallible. Early in 2014, Comcast upgraded to a new data collection platform that had “hardware limitations” that resulted in incorrect counts, according to last year’s NetForecast report. The problem wasn’t fixed until February 2015.

Those “limitations” led to underreporting of data, instead of over-reporting. But isn’t it possible that other errors could be discovered in the future, especially considering that NetForecast measured only 55 homes out of the nearly 24 million that subscribe to Comcast?

When asked that question, Sevcik said that NetForecast has been working on its methodology for years, and “we are pretty certain that if we are careful about where we measure, that we get a proper representative sampling of the various things that matter in meter accuracy.”

There are limited circumstances in which a customer could prove beyond any doubt that an ISP is measuring incorrectly. One such scenario would involve disconnecting the cable modem and router when leaving on vacation and checking whether the ISP measured any usage in your absence. Computers left on might download updates on their own, so disconnecting the home’s Internet access entirely may be the only way to be sure in this scenario.

More customers dispute accuracy

When Comcast measurements seem off, customers turn to third-party firmware like DD-WRT. Credit: DD-WRT forum.

In the absence of an official way to confirm Comcast’s meter readings, customers who want local measurements have relied on third-party source software to get at least a rough idea of their actual data usage.

Kevin, who lives in Rockwood, Tennessee, has used free Tomato firmware to measure his own Comcast data usage since mid-2013. He has found repeated discrepancies. In 11 of those months, Comcast’s data meter produced readings at least 10 percent higher than his own, with the difference reaching as high as 52 percent. There were also numerous months in which Comcast’s readings were lower than his own or nearly identical.

Kevin says he’s careful to measure properly. He makes sure that all his Internet traffic is routed through the device he’s measuring on, and he sets his router time to UTC to match Comcast’s measurement system. Kevin hasn’t exceeded his data cap enough times to be charged extra, but he’d like to be able to use more data in order to complete large off-site backups. (He owns a RAID storage system with more than 8TB of data.)

Kevin also worried about strange readings that Comcast displayed for his father, James, who lives nearby. In one case, Comcast listed James’s monthly usage at 27GB one day, then 325GB the next, before going back to 27GB a couple of days later, according to Kevin. There were also several months in which Comcast provided no data readings at all for James, as well as a period in which the company incorrectly listed his data cap as 600GB instead of 300GB.

When we contacted Comcast about this, the company investigated and figured out that James’s modem had been swapped for a new one, but the old modem wasn’t removed from his account. This led to incorrect data readings.

Comcast fixed that mistake and had a technician contact Kevin about the discrepancies between his own readings and Comcast’s. Upon reviewing a month’s worth of data readings from Comcast’s meter and Kevin’s own, they found 15 days in which Comcast recorded higher readings than Tomato and another 16 days when Comcast recorded lower usage than the Tomato firmware.

The Comcast rep was perplexed. “As he pointed out, this makes no sense,” because it wasn’t consistently wrong in the same direction, Kevin told Ars. “My impression was that he’s taking this quite seriously and unhappy about the discrepancies. I also got from him that even a five percent difference is higher than it should be, so they don’t consider large differences normal.”

The Comcast and Tomato meters mysteriously started showing almost identical readings in the first half of this year, with several months of discrepancies that were less than one percent. But the Comcast and Tomato meter readings grew apart again, with a Comcast undercount of 6.8 percent in May and Comcast overcounts of 15.7 percent in June, 5.5 percent in July, and 21 percent in August. Comcast never gave Kevin any official word on what caused the differences.

Comcast’s “perfect” meter produces a false reading

Liam, who works in IT and lives in Knoxville, Tennessee, has DD-WRT on his router to measure data usage. He wasn’t going anywhere near his data cap, but the online data usage tool Comcast provides to customers was showing readings far higher than his actual usage.

“Every month I was going over the data cap,” at least according to Comcast’s official meter, Liam told Ars. Liam said he does not subscribe to Comcast TV and uses Netflix extensively, “so I went to the [Netflix] website and turned down the quality so that I wouldn’t use as much data… I was watching [data] like a hawk.”

Liam said the Comcast website showed that he had gone over the cap for a few months late last year, even though his own readings on DD-WRT were hundreds of gigabytes lower. Last November, Liam’s wife was in the hospital, so the two of them were not home for about five days. Even during that time, Comcast recorded high data usage that pushed him over the 300GB limit.

Fortunately, Liam hadn’t used up his three courtesy months, so he wasn’t charged. And it turned out he and his wife had never gone over the 300GB cap at all: Comcast’s website was wrong. Initially, Comcast representatives said that Liam must have really used too much data. Alternatively, the reps suggested, he must have been victimized by malware, or someone gained unauthorized access to his Wi-Fi network.

But then, in December, the Comcast website suddenly started showing Liam’s actual, lower usage instead of the incorrect, inflated figures. Liam contacted Ars so we could investigate. A company representative offered Liam an explanation and an apology but only after we got in touch with Comcast.

“The Comcast rep stated that it was an ‘underlying table problem’ with the meter, causing wrong readings and was an error with the display only,” Liam told us. “He stated that Comcast used the actual data I was using and went by that and not the overage usage that I was seeing on their meter.”

“You guys created your own measurement.”

Our contact at Comcast explained to Ars that a software update corrected a “table display bug” that impacted Liam and that the underlying data being collected was accurate. The problem was related to a technical change in which Comcast switched its data meter from the device level to the account level, the Comcast spokesperson said.

Although Comcast claims it had the correct data all along, most of the Comcast representatives who spoke to Liam weren’t aware that he hadn’t actually exceeded the cap. Liam noted that he “talked to numerous Comcast support people, and they all blamed me or my equipment for the usage.”

The Comcast representative who finally cleared the matter up “apologized for that and [said] he would let someone know that they need to address the problem better,” Liam said.

Liam believes that Comcast increasing the monthly limit to 1TB “proved the cap was for financial gain and not network load balancing.” A Comcast VP did once admit that the cap is a “business policy” rather than a technical necessity.

Comcast CEO Brian Roberts has claimed that Internet data is just like electricity and gasoline, and that customers who use more should pay more. One of the Comcast representatives who told Liam that he must have used too much data made this same comparison. Liam countered that Internet data isn’t a consumable like electricity or gas, and that cable company data meters aren’t regulated like electric meters are.

“The weights and measures department takes care of that,” Liam told the Comcast rep during one of his phone calls with Comcast’s support department. “You guys created your own measurement.”

Jon is a Senior IT Reporter for Ars Technica. He covers the telecom industry, Federal Communications Commission rulemakings, broadband consumer affairs, court cases, and government regulation of the tech industry.