Smartphones have changed the way we drive, both by adding new distractions and by helping us get where we’re going with GPS-assisted directions and real-time information on traffic jams.

But what if smartphones could help eliminate some traffic jams, instead of just warning us when they exist? That’s the goal of a study using cell phone records and GPS data to track drivers’ movements and identify the sources of traffic.

The Boston Globe described the study today, noting that MIT and UC-Berkeley analyzed the cell phone records of 680,000 Boston-area commuters through call logs, “which identify the towers used to transmit calls,” allowing “the researchers to trace each individual’s commute, anonymously, from origin to destination.” This helped produce “one of the most detailed maps of urban traffic patterns ever constructed.”

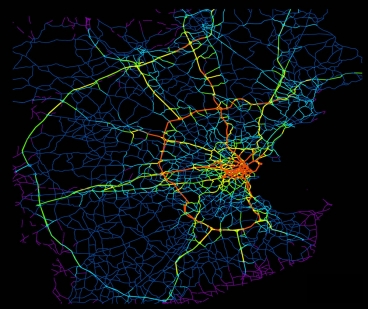

Boston-area roads. Red areas are the biggest sources of drivers. Yellow is next, then green, dark blue, and purple. Credit: MIT

The study was published in December in the journal Scientific Reports, and described in announcements by MIT and Berkeley. Such cell phone tracking helps bring traffic analysis patterns into the modern age, with statistics being constantly updated instead of becoming constantly outdated.

“This is the first large-scale traffic study to track travel using anonymous cellphone data rather than survey data or information obtained from U.S. Census Bureau travel diaries,” Berkeley’s announcement said. Studies chronicled traffic both in Boston and San Francisco.

In Boston, it turned out traffic jams are caused by just a few drivers in the grand scheme of things, the Globe noted. “What they found, perhaps surprisingly, is that during rush hour, 98 percent of roads in the Boston area were in fact below traffic capacity, while just 2 percent of roads had more cars on them than they could handle,” the Globe wrote. “The backups on these roads ripple outward, causing traffic to snarl across the Hub.”

Moreover, “By tracking the cell records, they found that it’s just a small number of drivers from a small number of neighborhoods who are responsible for tying up the key roads. Specifically, they identified 15 census tracts (out of the 750 in Greater Boston) located in Everett, Marlborough, Lawrence, Lowell, and Waltham as the heart of the problem, because drivers from those areas make particularly intensive use of the problematic roads in the system.”