If you want to appreciate the present, try living in the past for a few days.

Andrew Cunningham isn't the only one who's been dabbling in OS 9 within recent years. Credit: Andrew Cunningham

Andrew Cunningham isn't the only one who's been dabbling in OS 9 within recent years. Credit: Andrew Cunningham

It's Thanksgiving, all Ars staff is off, and we're grateful for it (running a site remains tough work). But one thing our Andrew Cunningham remains unthankful about is that time we forced him to take an extended dive back into the world of OS 9. We're resurfacing his experience from September 2014 for your holiday reading pleasure.

jonathan: perhaps AndrewC should have to use OS 9 for a day or two ;)

LeeH: omg

LeeH: that's actually a great idea

The above is a lightly edited conversation between Senior Reviews Editor Lee Hutchinson and Automotive Editor Jonathan Gitlin in the Ars staff IRC channel on July 22 of 2014. Using Mac OS 9 did not initially seem like such a “great idea” to me, though.

I’m not one for misplaced nostalgia; I have fond memories of installing MS-DOS 6.2.2 on some old hand-me-down PC with a 20MB hard drive at the tender age of 11 or 12, but that doesn’t mean I’m interested in trying to do it again. I roll with whatever new software companies push out, even if it requires small changes to my workflow. In the long run it’s just easier to do that than it is to declare you won’t ever upgrade again because someone changed something in a way you didn’t like. What’s that adage—something about being flexible enough to bend when the wind blows, because being rigid means you’ll just break? That’s my approach to computing.

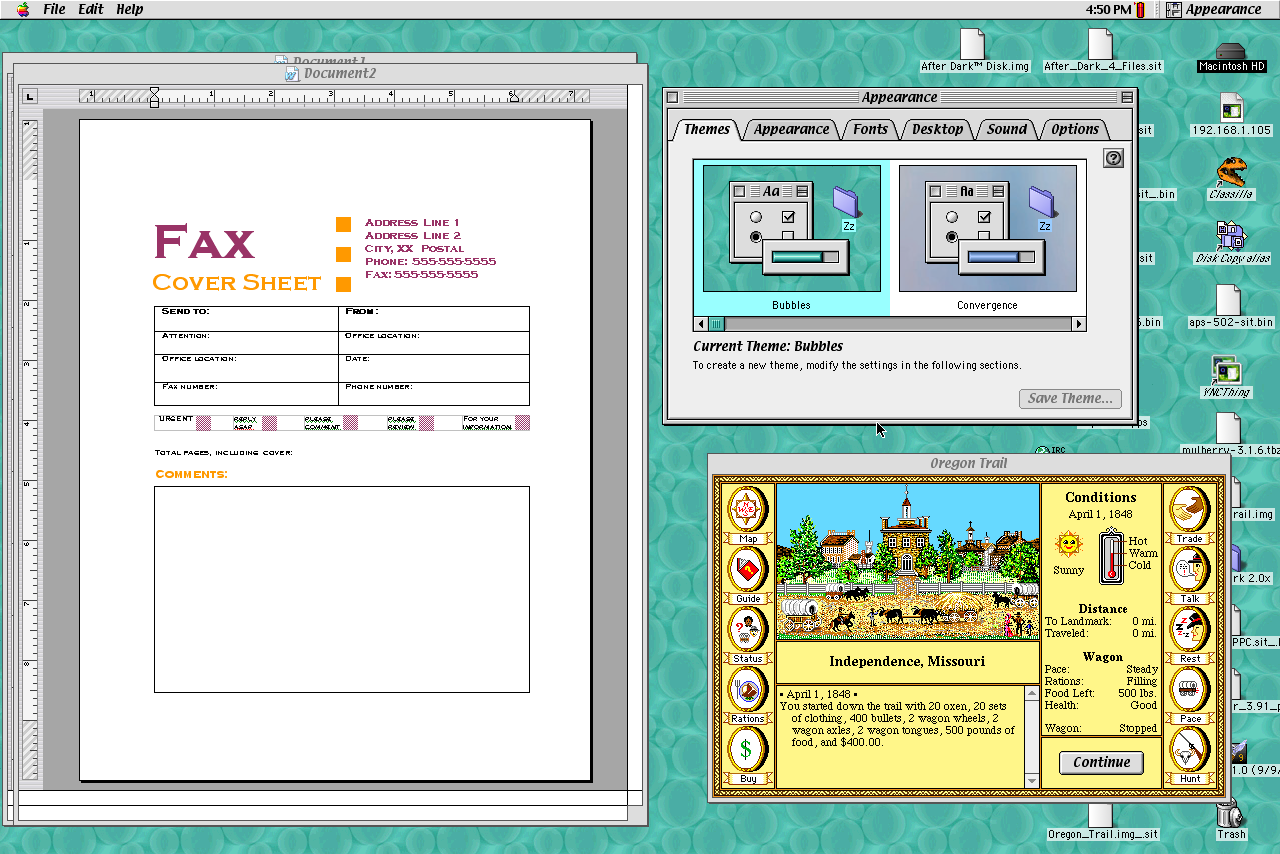

I have fuzzy, vaguely fond memories of running the Mac version of Oregon Trail, playing with After Dark screensavers, and using SimpleText to make the computer swear, but that was never a world I truly lived in. I only began using Macs seriously after the Intel transition, when the Mac stopped being a byword for Micro$oft-hating zealotry and started to be just, you know, a computer.

So why accept the assignment? It goes back to a phenomenon we looked at a few months back as part of our extensive Android history article. Technology of all kinds—computers, game consoles, software—moves forward, but it rarely progresses with any regard for preservation. It’s not possible today to pick up a phone running Android 1.0 and understand what using Android 1.0 was actually like—all that’s left is a faint, fossilized impression of the experience.

As someone who writes almost exclusively about technology at an exclusively digital publication, that’s sort of sobering. You can’t appreciate a classic computer or a classic piece of software in the way you could appreciate, say, a classic car, or a classic book. People who work in tech: how long will it be before no one remembers that thing you made? Or before they can’t experience it, even if they want to?

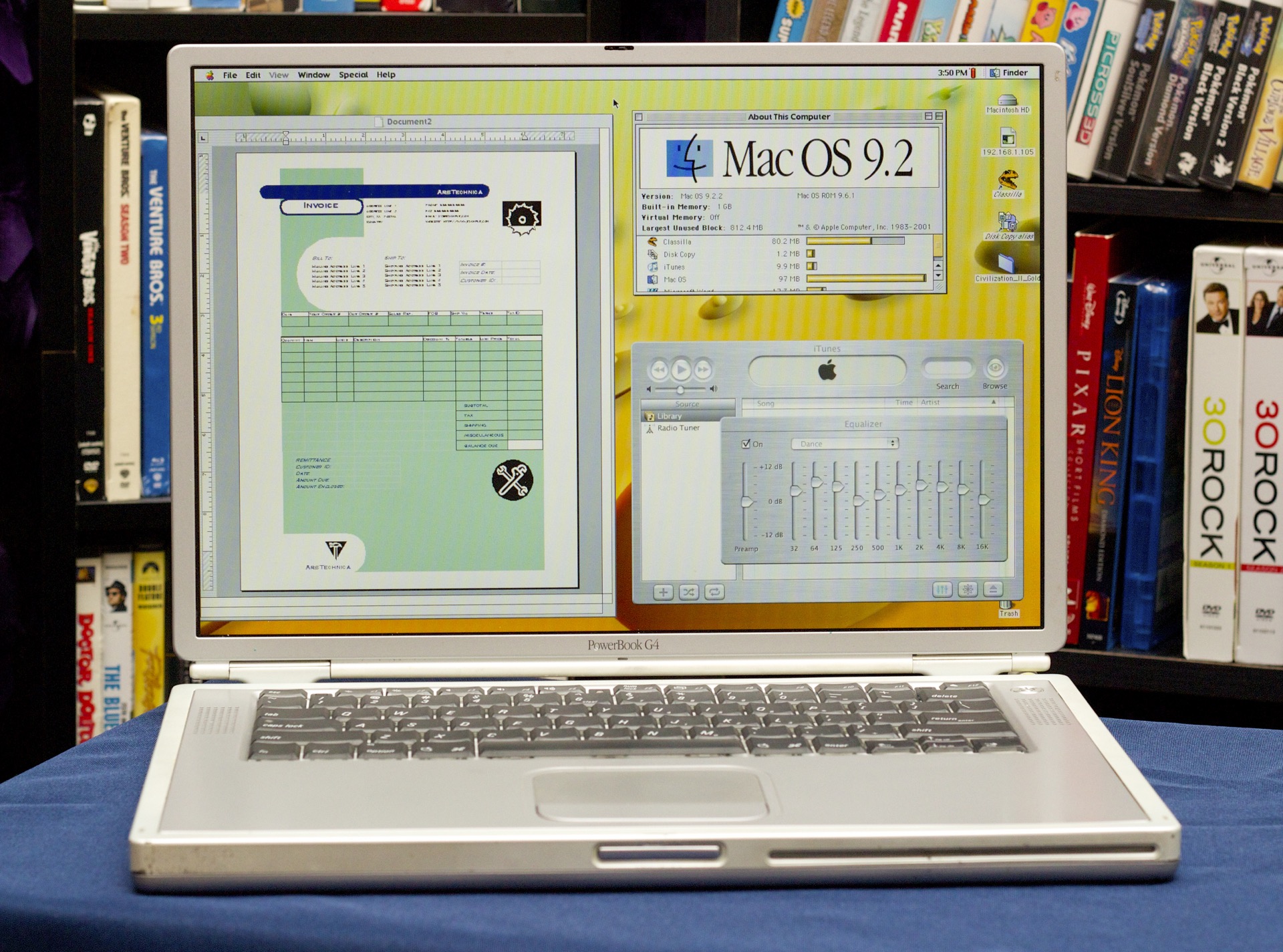

So here I am on a battered PowerBook that will barely hold a charge, playing with classic Mac OS (version 9.2.2) and trying to appreciate the work of those who developed the software in the mid-to-late ’90s (and to amuse my co-workers). We’re now 12 years past Steve Jobs’ funeral for the OS at WWDC in 2002. While some people still find uses for DOS, I’m pretty sure that even the most ardent classic Mac OS users have given up the ghost by now—finding posts on the topic any later than 2011 or 2012 is rare. So if there are any of you still out there, I think you’re all crazy… but I’m going to live with your favorite OS for a bit.

Finding hardware

My weapon of choice: a 2002 titanium PowerBook G4. Credit: Andrew Cunningham

My first task was to get my hands on hardware that would actually run OS 9, after an unsuccessful poll of the staff (even we throw stuff out, eventually). I was told to find something usable, but to spend no more than $100 doing it.

You’d think it would be pretty easy to do this, given that I was digging for years-old hardware that has been completely abandoned by its manufacturer, but there were challenges. Certain well-regarded machines like the “Pismo” G3 PowerBook have held their value so well that working, well-maintained machines can still sell for several hundred dollars. Others, like the aluminum G4 PowerBooks, are too new to boot OS 9. They’ll only run older apps through the Classic compatibility layer in older versions of OS X.

I didn’t want to deal with the pain of an 800×600 display, so the clamshell G3 iBooks were out, and I never really liked the white iBooks at the time—I found their keyboards mushy and their construction a little rickety. White plastic iBooks and MacBooks were never really known for their durability. Anything with a G3 also rules out support for OS X 10.5, which I’d want to install later to actually get stuff done on this thing.

The laptop I decided to go with was the titanium PowerBook G4. While these weren’t without quality issues, they at least promised usable screen resolutions and Mac OS 9 compatibility. They also tend to fall right where we’d want them on the pricing spectrum—old enough to be cheap, but not so old or well-loved to be collectors’ items.

The Apple video that introduced our titanium PowerBook to the world.

Notes on that video:

- The PowerBook G4 is called a “supercomputer.” You keep using that word…

- What does this music have to do with anything?

- Phil Schiller’s hair!

- Jony Ive pronounces “aluminum” in the American fashion, rather than “aluminium.”

- Titanium was better than aluminum in 2001, but it apparently stopped being that way later in the decade.

- Mac OS X had been out for about six months at this point, and it’s mentioned by name once in the ad, but all of the shots of the computer in action show it using Mac OS 9. The first few OS X releases are best forgotten.

Finding used computers on Craigslist is a great way to get scammed and left for dead in some alley in Brooklyn, so I turned to eBay. Many used computers on eBay are being sold “as-is” or for parts, a last-ditch effort by their owners to get some kind of value out of them while also getting rid of them. It’s a bit risky, but you can save some money if you buy one of these dinged-up models and fix it yourself.

For about $75, I was able to pick up an 800MHz model with 512MB of RAM and a 40GB hard drive. It worked but included a non-working battery, no power adapter, and a wonky power jack. For $8.86, I picked up a new power jack (happily, it was separate from the main logic board in those days), and another $15 got me a used genuine Apple adapter (third-party substitutes are widely available for a few dollars less, but I am terrified of cheap off-brand chargers). That brought my total to a little under $100.

Replacing the wonky old power jack with a working replacement was both simple and cheap, though like many old laptops the PowerBook is pretty ugly on the inside compared to modern systems.

Credit: Andrew Cunningham

Replacing the wonky old power jack with a working replacement was both simple and cheap, though like many old laptops the PowerBook is pretty ugly on the inside compared to modern systems. Credit: Andrew Cunningham

I could have spent between $25 and $95 on a working third-party battery. I just happened to have 1GB of PC133 SDRAM (the maximum amount supported by this PowerBook) buried in my closet, though I would have shelled out another $12 or so if I’d had to pay for it. These upgrades aren’t strictly necessary, and dumping a lot of extra money into a computer this old is unlikely to raise its value much. I did go $30 out-of-pocket to replace the rickety old hard drive with a shiny new one with a faster rotational speed and a higher capacity, though. Sometimes you’ve got to treat yourself.

My iFixit screwdriver kit and the handy iFixit repair guides helped me crack the case, replace the power jack and drive, and swap out the RAM. All repairs went off without a hitch, and I used some canned air to blow out some of the dust and grit that had gathered inside the case. I cleared my 2012 iMac off my desk and replaced it with the repaired PowerBook. Time to get to work.

Getting used to Mac OS 9 and finding software

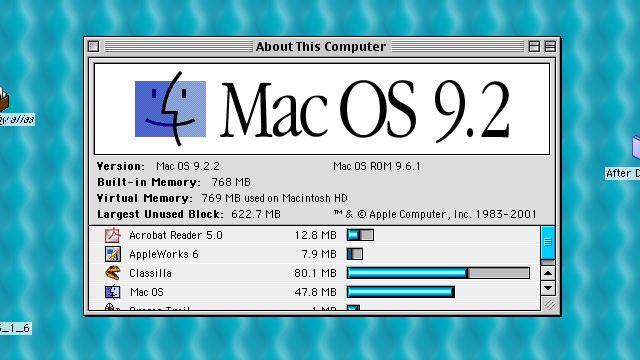

Welcome to Mac OS 9! We hope you like grey rectangles. Credit: Andrew Cunningham

I booted to the classic Mac OS desktop, thanks to Mac OS 9.2.2 install media from Ars Senior Science Editor John Timmer. Even for someone who has primarily used OS X, this is still recognizably Mac OS, even if its underpinnings are much different. It looks like the Windows 98 version of Mac OS.

There are oddities to get used to, though. Niceties like scroll wheels and right-clicking aren’t supported, even with an external mouse, and the third-party software created to enable those features didn’t like my Logitech wireless mouse. The concept of “Control Panels” that are installed and used like individual apps is alien to someone used to the all-in-one convenience of System Preferences. And connecting the PowerBook to my router required a trip to the TCP/IP Control Panel to get things working—the OS didn’t just detect an active network interface and grab an IP address as it does now.

I can understand why some people wanted to stick with Mac OS 9, especially in the early days of Mac OS X when extra clock speed and memory were expensive and harder to come by. Mac OS 9 feels much faster on the 800MHz G4 than does OS X 10.4 or 10.5, and when the system is working smoothly things open and close pretty much instantaneously. That is, unless you get a pop-up message that momentarily freezes the OS, or you have an odd, possibly memory-related crash that requires a restart. Even back in the earliest, slowest, buggiest days of OS X, it brought much-improved stability and memory management to the table, and it’s something we’ve come to take for granted.

The best way to get started if you’re revisiting a relic is to find the pockets of people on the Internet who still use it. For any product that was sufficiently popular in its day, you’ll still be able to find some group of people, somewhere, that continues to sing its praises (remind me to tell you about the time I dissed the Apple Newton in an article). First I found LowEndMac.com’s sort-of-active Mac OS 9 Google group, and from there I was pointed to the abandonware archive at Macintosh Garden.

Abandonware (a handy portmanteau of “abandoned” and “software”) is one of those software “gray areas,” sort of like old-school PC and console game emulation. Technically, using this software without paying for it constitutes “stealing,” because it was never offered up for free back in the day. But many of these companies aren’t even around anymore, and the ones that are still around aren’t really interested in offering or maintaining decades-old games and productivity software.

Macintosh Garden is full of such abandonware, and for this article we’re going to download it indiscriminately in the name of Science. Whether you’ll still find these apps useful depends on what you’re trying to do, though.

Trying to work? Good luck

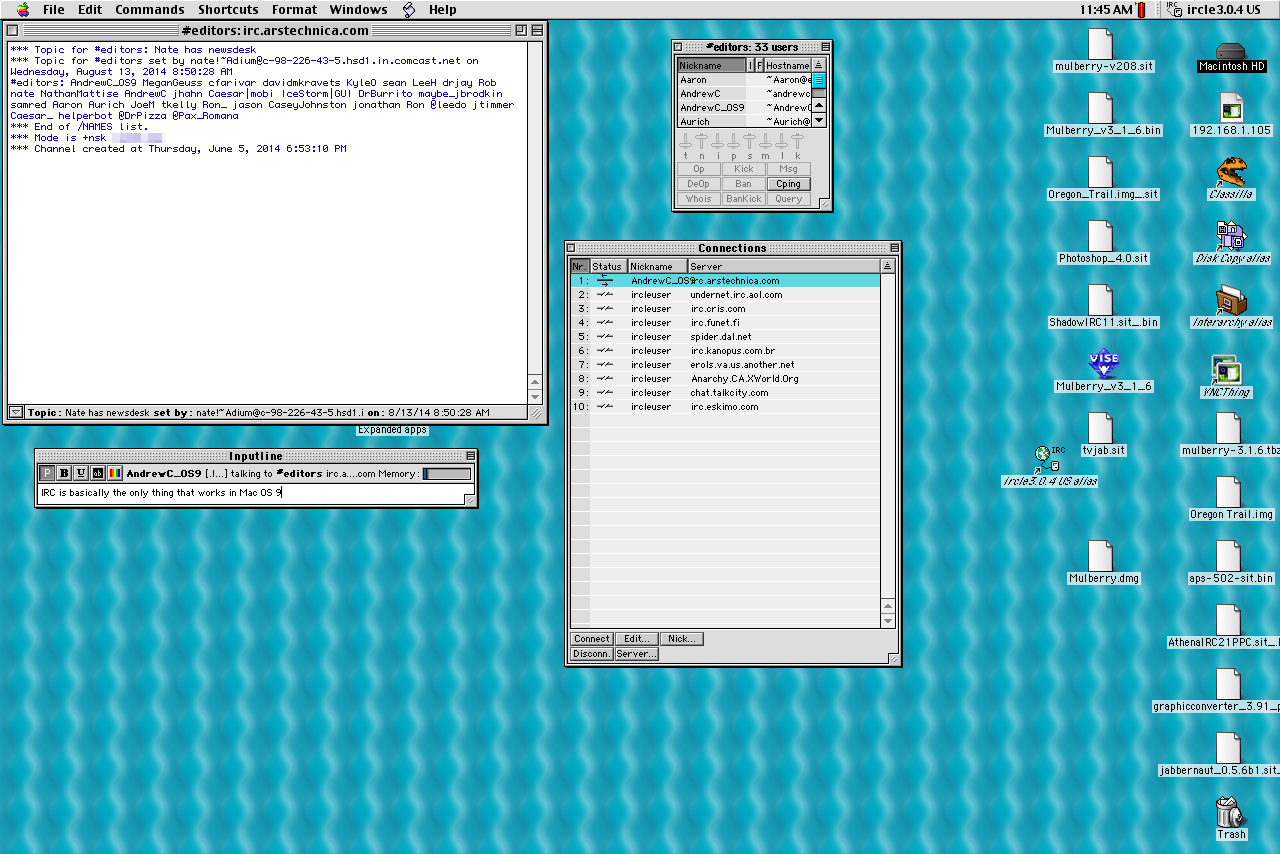

I could connect to our IRC server in Mac OS 9, and that was really about it.

Credit: Andrew Cunningham

I could connect to our IRC server in Mac OS 9, and that was really about it. Credit: Andrew Cunningham

I originally had high hopes that I’d be able to do my job using Mac OS 9, since on paper most of the tools I need are readily available. We used IRC and an XMPP server for communicating (now we use Slack, but it supports connections using the same protocols), and our Office 365 server supports IMAP connections. It might be a little weird to go back in time for a couple days, but when you get down to what I actually need to get my job done, it’s a pretty short list.

When putting theory into practice, I ran into two major problems. The first is that Mac OS 9 can’t run anything that even attempts to approximate a modern Web browser. Browsers of the day (Internet Explorer 5, Netscape) stopped being able to render pages properly a very long time ago, and other smaller browsers like iCab that used to support Mac OS 9 no longer do. My one option was “Classilla,” a distant relative of the Mozilla suite that later became Firefox.

Classilla was last updated in very early 2013, but its rendering engine is much older, and it still choked on just about every page I threw at it. Telling Classilla to put a page together is like telling a blind construction worker to build a house using a blueprint that was scrawled on a place mat by a drunk baby. Forget using Web apps. Forget getting stories into our WordPress CMS. Forget being able to click on links in IRC to open them. It ain’t happening.

My efforts were further hampered by the near-nonexistent state of desktop operating system security in the late ’90s and early 2000s. In this post-Snowden era, we often worry that the encryption hardware and software we rely on is flawed in some way that will allow it to be circumvented. In the early 2000s it wasn’t even a given that applications would support basic SSL/TLS encryption.

Most e-mail apps I tried (Eudora, Microsoft Entourage 2001, Mulberry) didn’t support SSL encryption at all, or they supported some older version that our e-mail server didn’t care for. Entourage nearly worked—I could receive mail, albeit with many connection errors, but I could never send it. Mulberry offered an SSL plugin once upon a time, but the version that works with Mac OS 9 (3.1.6) is impossible to find, since the app’s original creators closed up shop, and the open-source version (4.0.8) only works in OS X. And since Classilla makes such a mess of things, the Web client isn’t an option.

And it goes without saying that syncing files between Mac OS 9 and any other system just isn’t going to happen (I mostly use Dropbox, but the service you use doesn’t make a difference). Even using a network share isn’t possible—Mac OS 9 doesn’t support Windows’ SMB protocol, and its version of the AFP protocol is too old to interface with my Mac Mini server running Mavericks. I was only able to do some file transfers using FTP, yet another unencrypted and insecure protocol.

Most people’s habits have changed drastically since the year 2000. Back then, your computer was the one computing device you had. You didn’t need to sync stuff to a phone or a tablet or another computer, because you didn’t have a phone or tablet or another computer. Steve Jobs called the computer the “digital hub” for all your other devices, and the software reflects that philosophy. Mac OS 9 is an island. These days, your computer is (at best) a first among equals.

All of this stuff adds up to a computer that can’t really get much work done anymore, especially if the place you work is the Internet. Again, unlike old-school DOS, even the most ardent users of classic Mac OS have abandoned it. And since users have abandoned it, developers have abandoned it. Trying to drag a Mac OS 9 system kicking and screaming into the modern age is a fun thing to try for an afternoon or two, but it’s ultimately a pointless exercise. This old operating system is really only useful when you’re trying to run old programs exactly the way they ran back in the ’90s.

Classic gaming

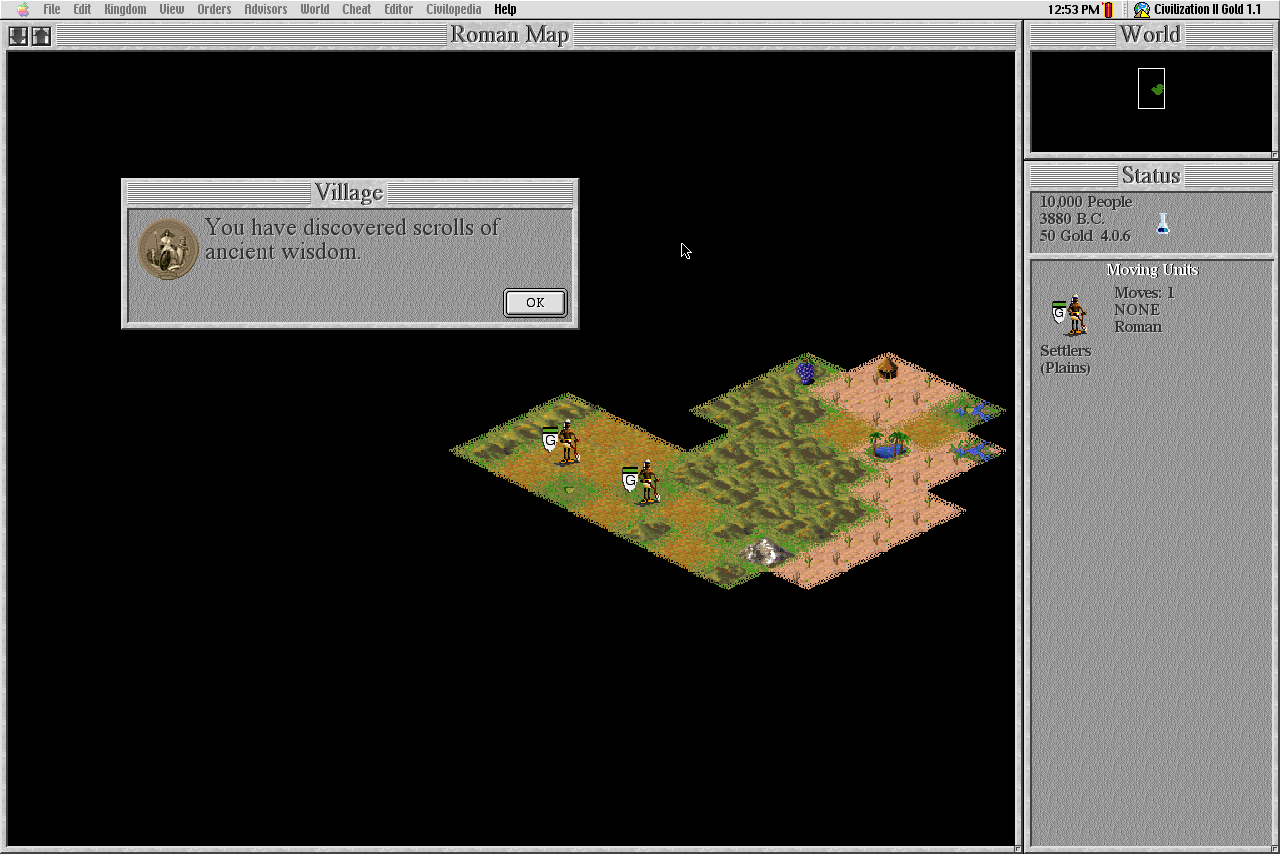

Geez, this place is just lousy with scrolls of ancient wisdom. Credit: Andrew Cunningham

Most of my pre-OS X Mac experiences happened on computers in our school’s lab, and most of them centered around games. A whole bunch of them were educational games that were supposed to teach me about long division and running a hot dog stand and traveling to Oregon during the Olden Days, but in any case they appealed to my SNES-addled brain.

If you want to relive these games exactly as you remember them, there’s no substitute for real Mac OS running on real PowerPC hardware. Classic Mac emulators exist (in the form of PearPC, Sheepsaver, and Basilisk II), but they often come with their own stability and incompatibility problems. Macintosh Garden’s list of old games is pretty expansive, and I was able to find a lot of my old favorites there.

If you run into any problems gaming on a machine like this, it might be that Mac OS 9 is actually too new for the stuff you want to run—crazy, I know. Oregon Trail plays without sound, a known issue, and you’ve got to do some fiddling to get those old After Dark screensavers up and running. If you’re running into these kinds of edge cases, you’ll need to get even older hardware or try your luck with some emulation.

Aside from the occasional bug, old classics like Civilization II or Age of Empires 2 (which I played on the PC back in the day), ran just fine. Once I discovered that I couldn’t actually get anything done in Mac OS 9, I decided to fire up my Mac OS X 10.4 partition and just play them in Classic mode instead.

Classic Mode is a pretty good way to run Mac OS 9 apps without having to deal with Mac OS 9. Sadly, support for Classic was removed from OS X 10.5, even for PowerPC systems. Andrew Cunningham

As someone who was never a Mac user in the PowerPC days, I was impressed by just how solid Classic really was. It ran those old Mac OS 9 apps and made them work seamlessly with OS X apps. In a newer system with 1GB of RAM, you barely notice the small amount of extra overhead you deal with by running OS 9 alongside OS X (around 30MB according to Activity Monitor, plus whatever the apps themselves consume). It’s really too bad that Apple killed off Classic support for PowerPC Macs in OS X 10.5, the first all-new OS release of the Intel era and the last one that supported any PowerPC hardware.

Takeaways

In the end I really couldn’t do a whole lot with classic Mac OS, which was kind of too bad. If anything, experimenting with it validated my “go with the flow” approach to hardware and software updates. No matter how much you love something, time marches on. The tech industry is a hungry beast that demands constant growth and change, and one day your favorite old piece of software will be so far behind the times that nothing you can do will help catch it up. Just as it’s not possible to see what Android 1.0 was like when it was new, installing Mac OS 9 on an old PowerBook in 2014 does not actually show you what it was like to use Mac OS 9 in 1999.

From a practical perspective, this is OK, because I am totally fine with never using 15-year-old software in my day-to-day life. From a historical perspective, though, it makes it harder to appreciate Mac OS 9’s strengths (low resource usage, good performance on old hardware) and the concepts it introduced that modern Mac buyers still use every day.

Modernizing, kind of: Running Leopard

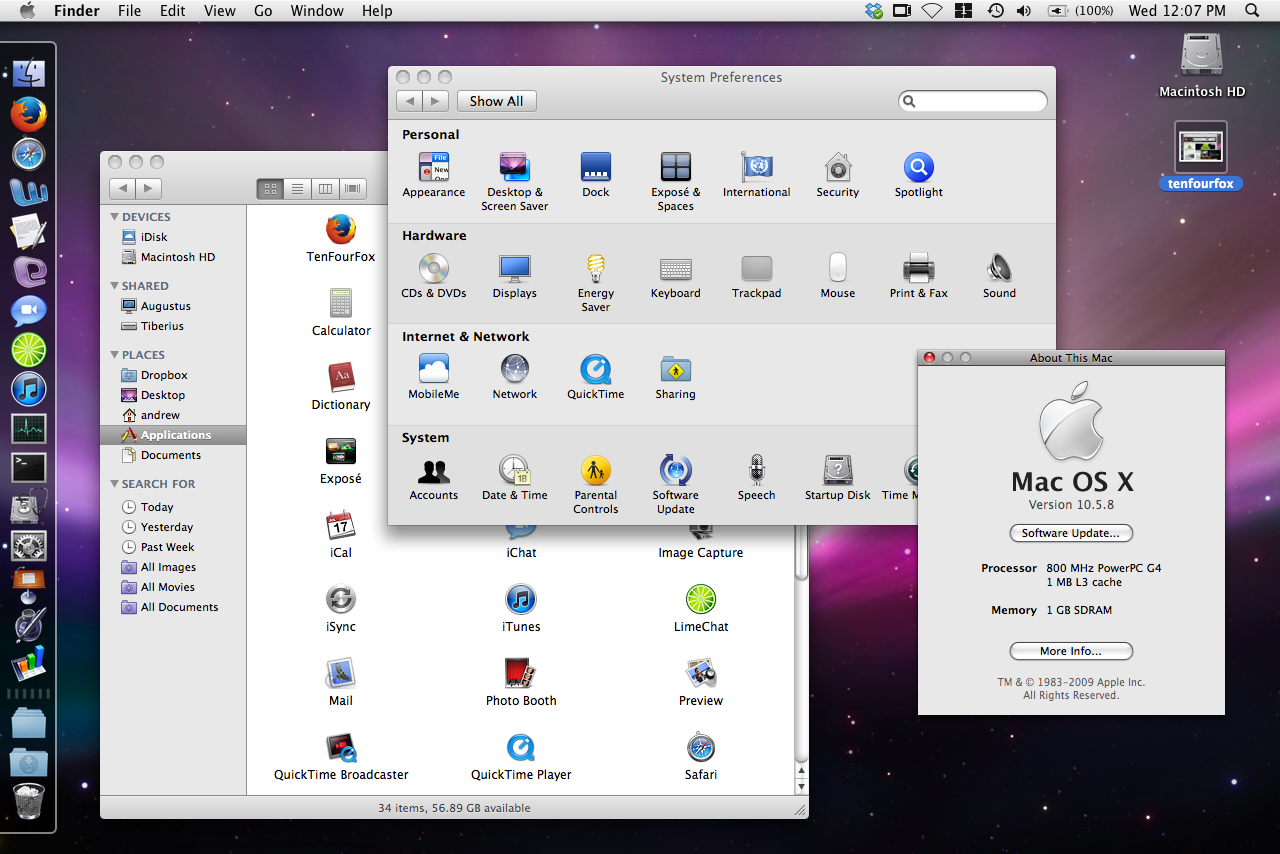

After messing around with Mac OS 9 and Classic mode for a bit, we installed OS X 10.5 to see how it worked.

Credit: Andrew Cunningham

After messing around with Mac OS 9 and Classic mode for a bit, we installed OS X 10.5 to see how it worked. Credit: Andrew Cunningham

One of the reasons I went with the Titanium PowerBook is that I knew it would be able to run later PowerPC-compatible OS X versions without too much trouble, making it possible to actually use this thing for something useful (or, at least, making it easier to flip it on eBay after writing this article and making the necessary repairs).

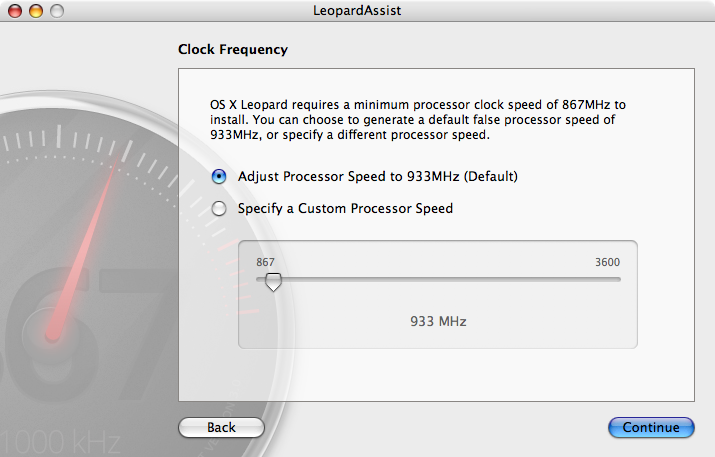

Since this is an 800MHz PowerBook, it technically doesn’t meet the system requirements for installing Leopard. Without an 867MHz G4 or better, the standard OS X 10.5 install media will refuse to install. System requirements were pretty fluid for PowerPC Macs, though, and users came up with all kinds of creative ways to trick their systems into running software they technically weren’t “allowed” to run.

LeopardAssist runs in OS X 10.3 and 10.4, and it can be used to fool slower G4 systems into installing Leopard.

Credit: Andrew Cunningham

LeopardAssist runs in OS X 10.3 and 10.4, and it can be used to fool slower G4 systems into installing Leopard. Credit: Andrew Cunningham

For Mac OS X 10.5 on slower G4s, the best option is LeopardAssist. It’s a dead-simple tool that temporarily tricks the system into thinking it has a CPU fast enough to meet the 867MHz requirement—it doesn’t actually change the clock speed, so there’s little risk of damage to your hardware, and the true clock speed value is restored as soon as the system passes Leopard’s requirement check. I inserted the OS X 10.5 install DVD, ran LeopardAssist from the OS X 10.4 install, and put Leopard on a separate partition.

You still won’t be able to run the newest versions of most applications on PowerPC Macs, which developers began ignoring long before Apple released its last updates for Leopard in 2011 and 2012. Still, it’s easy to find reasonably modern software that can cover all of the basics.

Leopard isn’t exactly snappy on an 800MHz G4, but it’s much closer to the modern OS X experience and can still run a fair number of near-modern apps.

Credit: Andrew Cunningham

Leopard isn’t exactly snappy on an 800MHz G4, but it’s much closer to the modern OS X experience and can still run a fair number of near-modern apps. Credit: Andrew Cunningham

Microsoft Office 2008, the last PowerPC-compatible version, stopped being supported in 2013, but Word, Excel, and PowerPoint still handle most documents just fine, and Entourage (ugh) can connect to our Office365 server either through IMAP or Exchange. The built-in Mail.app didn’t pick up official Exchange support until OS X 10.6, but IMAP should still work fine if you want to stick with Apple’s apps. iChat can connect to XMPP and Google Talk, or you can grab an older version of Adium in a pinch. A slightly older version of Limechat, my preferred OS X IRC client, works just fine in 10.5, and to my immense surprise the current version of the Dropbox client still supported the PowerPC architecture under both 10.4 and 10.5 (since this was written, though, Dropbox has officially dropped all support for PowerPC, even if you can find and run the old client).

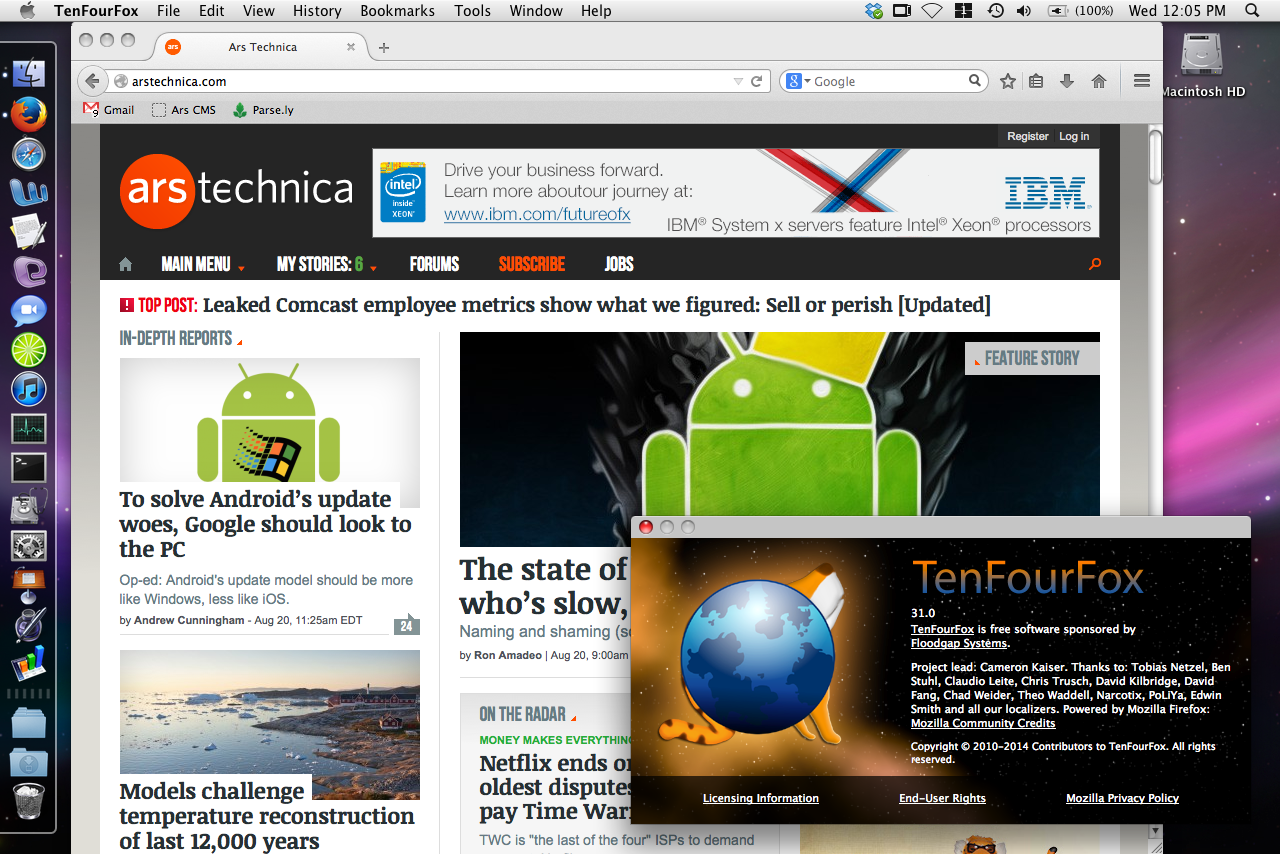

The most important bit, the browser, is a little trickier but still workable. The newest version of Safari for 10.5 (5.0.6) can still render a bunch of pages without choking, but the security risks of running a three-year-old browser were unacceptably high for me. Salvation (of sorts) came in the form of TenFourFox, a PowerPC fork of Firefox based on the browser’s extended support release. It was just updated to version 31, complete with the new “Australis” interface and compatibility with Sync and other Firefox niceties. Plus, it maintains support for PowerPC chips going all the way back to the G3 as long as the Mac can run OS X 10.4 or 10.5.

TenFourFox brings most of the features from the Firefox ESR releases to PowerPC systems running 10.4 and 10.5. I don’t love it, but it gets the job done.

Credit: Andrew Cunningham

TenFourFox brings most of the features from the Firefox ESR releases to PowerPC systems running 10.4 and 10.5. I don’t love it, but it gets the job done. Credit: Andrew Cunningham

As great as it is that there are still brave souls keeping the lights on for PowerPC users, TenFourFox is not my favorite browser. Scrolling on the 800MHz PowerBook was constantly choppy and unresponsive, where Safari is at least capable of something approximating smoothness. The browser is RAM-hungry to a fault (it used around 206MB to load the Ars homepage, compared to 96MB for Safari). The official development blog, while very informative, makes it sound like Firefox is always a feature or two away from being completely un-port-able. It can’t use plugins, though the plugins still available for PowerPC Mac OS X are long out of date anyway. And that icon is not my style. I replaced it with the official Firefox icon to make myself feel better.

In any case, TenFourFox does a respectable job of rendering pages properly, and I’m sure it runs much better on newer 1GHz-and-up aluminum PowerBooks and iMacs than it does on this old titanium G4. One thing I’ll say about both OS X 10.4 and 10.5 on this hardware is that it’s laggy no matter what you’re doing. Mac OS 9 is pretty spartan by modern standards, but it’s quick to respond to user input, at least as long as it’s not hung up on something. It’s usable, and I could actually do pretty much everything I needed to do to get my job done on it. It’s just not a very pleasant experience compared to a modern Mac.

Stuff you take for granted on a modern, multi-core computer with an SSD and lots of RAM is totally different on a system this old. Having dozens of browser tabs open at once, playing some music or maybe a video in the background, syncing Dropbox files, even watching animated GIFs consumes precious CPU cycles that an 800MHz G4 doesn’t have to spare. Exceeding the computer’s once-impressive-but-now-paltry 1GB of RAM, something you’ll do without even thinking if you fire up TenFourFox, prompts virtual memory swapping that grinds things to a halt. In principle, I admire the people committed to making this hardware last as long as it possibly can, but in practice I couldn’t return to my MacBook Air quickly enough.

Change

The past and the future. Credit: Andrew Cunningham

People love to complain about change. Those complaints aren’t always unwarranted. We live in an era of constant updates, where your browser changes every six weeks, and your operating system changes every 12 months. Who even knows how often they’re changing Gmail and Twitter and Facebook? The idea of supporting and using a single OS for 13 years seems completely absurd. Sometimes you just want everything to stand still for, like, a second.

But really, most people are pretty change-tolerant as long as the change is gradual and incremental and doesn’t completely flip their worlds upside-down (looking at you, Windows 8). Moving from Mac OS 9 to Mac OS X 10.4 on this old PowerBook drives home just how big the change from classic Mac OS to Mac OS X was, and yet there are enough similarities and constants there that you won’t be completely lost if you jump from one to the other.

And the change didn’t stop there. Moving from 2007’s Leopard to 2013’s Mavericks is a deceptively large change. The interfaces aren’t so different, but the smartphone completely changed the face of computing in those six years, and everything from app distribution to data storage to the way we think about operating system updates has shifted in response. It’s a sea change belied by the similar icons and toolbars and docks.

OS X is just a couple of months from changing yet again—Yosemite is probably the biggest version-to-version visual overhaul of Mac OS we’ve gotten since the jump from version 9 to version 10 (er, X), and El Capitan makes still more changes. The design will change. Some of us will complain. Most of us will get so used to the changes that we forget how things worked before. And then we’ll do it all again next year.

Listing image: Andrew Cunningham

Andrew is a Senior Technology Reporter at Ars Technica, with a focus on consumer tech including computer hardware and in-depth reviews of operating systems like Windows and macOS. Andrew lives in Philadelphia and co-hosts a weekly book podcast called Overdue.