Sub Pop Records has signed some of the most famous and influential indie bands of the last 30 years, including Nirvana, Sleater-Kinney, The Postal Service, and Beach House. Over time, the stars and hits have changed and the formats have evolved as well, from vinyl to CDs to MP3s. In recent years, however, the label has started releasing new albums on a medium few thought would ever see a comeback: the cassette.

There are obvious downsides to cassettes. Listeners can’t skip tracks easily. Over time, the magnetic tape can stretch, distort, and even snap.

On the flip side, tapes are relatively durable, able to flop around on the floor of a car for years and still work when slotted back into a player. Most messed-up cassettes can be fixed with patience and a pencil, and there’s something about making a mix-tape on actual tape that shows more time and effort that creating a playlist in Spotify.

Music labels see upsides to cassettes as well, which are cheap to produce and distribute, giving listeners something physical (with art and liner notes) to go along with an MP3 download. For whatever combination of functional, nostalgic, or economic reasons, labels like Sub Pop are bringing back tapes.

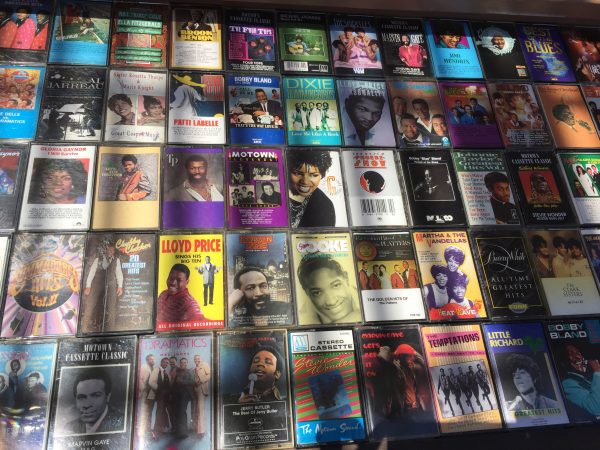

But they and their customers certainly aren’t the only ones who still use cassettes. In fact, there’s one big user group that never entirely stopped using the old school technology. The United States prison system has the largest prison population in the world and many of its inmates listen to their music on tape. For this group, cassettes aren’t necessarily the cheapest or hippest way to listen to music; in some cases, it’s the only way.

In many prisons, tapes have to meet special criteria before they’re allowed inside: tapes have to be entirely clear and sonically welded. The reasoning behind this isn’t consistent from prison to prison, nor is the logic entirely sound—but generally the policies stem from attempts to reduce smuggling and to exclude objects that could be easily weaponized (like the edge of a broken CD). The case usually also has to be completely see-through, so the entire package is easy to inspect.

There is an entire industry that’s grown up around the shipping of packages to prisoners that conform to the prisons’ guidelines. The rules they follow can seem arbitrary at times. For instance, CDs might be banned because they can have sharp edges if they’re snapped, but tuna cans and their sharp metal lids might be totally permissible.

Still, these businesses (like the inmates they serve) have little choice but to follow the rules. Various prisons have opacity-related guidelines for other gadgets as well, leading to see-through plastic televisions, computers, tablets, and other devices.

Some prisons have started to allow MP3s, which seem like a sensible format since sound files leave no space for smuggling. But when prisoners buy a digital music file through their commissary, it sometimes comes with a catch: some prisons have policies against letting (even adult) prisoners purchase and download songs with Parental Advisory warnings—this limitation is probably a big reason for the popularity of tapes. The content of tapes isn’t controlled as tightly. MP3s are also harder for inmates to trade around since they are tethered to a single MP3 player.

So, despite the new technology being available, a lot of inmates (even in prisons where there are other options) still prefer cassettes…at least for now. Prisons tend to be late adopters of technology, so maybe one day all prisons in the US will make the switch from cassette to digital. Or maybe they’ll skip from tapes to CDs first, just to be illogically chronological.

Whatever the format, the important thing to most prisoners is the ability to listen to and share music. Sometimes, inmates in solitary confinement will call up to their fellow prisoners on the floors above, asking them to play a favorite song on speakers. For prisoners lacking finances and freedoms, sharing music with another inmate is an expression of solidarity and means of forgetting where they are—if only for the length of a song.

Some of the recordings in this episode came from the film The Prison in Twelve Landscapes by Brett Story.

The audio version of this story included the voices of Adolfo Davis and Efrén Perédes Jr. Both are serving life-sentences in prison for crimes they were convicted of as juveniles. You can follow Efrén’s case here, and Adolfo’s here.